Archaeologists of the Digital

Text by Mirko Zardini

Where to Begin?

The obvious would have been to start from the intense debate over the digital in architecture that coalesced during the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s — a debate that has accompanied most of the production and discussion in the field ever since — that has been well documented in periodicals, books and websites and assessed by countless authors and commentators.

We decided, however, to suspend this natural instinct and start instead from a handful of ground-breaking projects. Our task, in line with recent works in media archaeology, focused on investigating concrete ideas and results of these foundational digital works. We inspected a series of layers — authors, machines, software, companies, related disciplines, institutions, etc. — not only to articulate a historical account but, more importantly, to better understand the context that allowed these projects (and technologies) to achieve prominence.

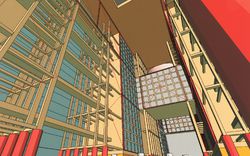

Archaeology of the Digital is a project envisioned by the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), curated by Greg Lynn, based on the acquisition and collection of approximately twenty-five projects. These works were produced between the late 1980s and the early 2000s and embody inventive ways of engaging the digital. This first phase — entitled Archaeology of the Digital, comprising an exhibition and this publication presents four pioneering works by Peter Eisenman, Frank Gehry, Chuck Hoberman, and Shoei Yoh. In all fairness, a fifth actor should be added to this list; an inanimate actor who takes different forms and names: machine, computer, manual, software, code, script, etc. This technological constituent — sought, found, tested, modified and even invented by the architects themselves in order to realize their ultimate vision — attained a life of its own and made the production of these projects possible.

Which Digital?

Defining what we meant by digital, when the word is relentlessly used to describe anything produced with the assistance of a computer — an almost unavoidable condition nowadays — proved to be a hard task. However, the digital we refer to in this archaeology is not defined by this pervasive usage of technology, nor is it defined solely by the use of computing power in the search for higher efficiency and speed of production. The digital we refer to is defined by experimental projects and ideas, from a specific period of time, which engaged proactively in the creation and use of digital tools to reach otherwise inaccessible results.

Read more

Why this Period?

The connection between cybernetics and architecture can be traced back to the 1960s, to places like England and the United States, and to people like Lionel March or Christopher Alexander, among many others. Early collaborations focused on analyzing complex architectural and urban problems and creating environments that brought the user and the computer closer and represented a new way of thinking about architectural possibilities. In this context, the association of Cedric Price and Gordon Pask for the Fun Palace project is a prime example. As noted by Stanley Mathews, at that moment, the latest advances in cybernetic technology appeared to hold endless promise as a means of reconciling “bricks and mortar” with the multivalent and ever changing functions and programs of the project. For the Fun Palace, Price had hoped that an autonomous cybernetic control system would allow users to shape their own environments.1

But it was during the late 1980s and the 1990s, when architectural research and development enterprises pressed for intensive investigations in technological advancement and computer-based tools, that the digital became instrumental in the definition of particular visions and a new architectural direction. Moreover, the 1990s were notably defined by the field’s near-total dismissal of history and theory, which were promptly replaced by technology driven practices. This change was further intensified by the easy access to the World Wide Web, cellular telephones, software and computational capacity, among countless other tools.

Interestingly, this period was also the beginning of a vanishing interest in the “public” component of architecture. This waning — furthered today by policy reforms that are weakening even Europe’s welfare states — provided fertile ground for architectural projects to be construed as interiorized tasks. The results were frequently ideas of architecture where the entity achieved leading importance, often to the detriment of multiple external circumstances that offered less and less resistance. The projects resulting from this shift are often in sharp contrast with the friction we see and experience in the world today and seem to celebrate a vision of harmonious, fluid environments devoid of conflict.

Why Archaeology?

A few current trends in media studies seek to displace or exclude the social, cultural, economic and political context from research. Recent conceptual developments in architecture, usually justified by the idea that the electronic and the mechanical ages are incompatible worlds in collision, are emerging from a similarly exclusive vacuum that fosters a self-referential and hermetic discourse. According to Sanford Kwinter, continuing to think in such sterile ways can have no other effect than to hide from ourselves their political dimension.2

The archaeology in Archaeology of the Digital is then a model of exploration that provides the framework needed to inspect archives and projects. The close readings of different media, recordings, professional affiliations, tools, software and processes, offer compelling evidence that history is not a seamless, progressive story but rather an incessantly rewritten narrative, modified by new scrutiny.

A (Great) Loss?

The idea of archaeology, in the case of this first exhibition, also suggests a great sense of loss. A loss marked by the fact that most of the digital material produced for these projects — with the exception of Frank Gehry’s Lewis House — has been lost. As noted by Greg Lynn in his introduction to this book, “The iterations of digital files, the native digital objects and data-sets, as well as the tools and machines used in their production are disappearing with every migration to a new operating system, every move of an office and every upgrade in hardware.” Will it be possible to research these projects without having access to their digital files?

The imminent danger of losing even more digital records compelled us to take a first step towards collecting this type of material. While we are not sure what the future of this enterprise looks like, we do believe that the work could not be further delayed and, given the challenges and scale of the tasks ahead, we look forward to seeing other institutions join and collaborate with this initiative.

Why the CCA?

The initial efforts on behalf of the CCA to examine — within a more general context — early digital experiments in architecture can be traced back to November 2004, to a seminar entitled Devices of Design, held in collaboration with the Daniel Langlois Foundation. The scope of the meeting was to investigate the different strategies deployed by architects, during the 20th century and at the beginning of the 21st, in their search for new ways of imagining and building architecture. Briefly outlined, Bernard Cache’s “Non-standard Digital Folding” and Greg Lynn’s “Going Primitive” conceptually anchored the gathering, following Derrick De Kerckhove’s introduction to the subject, a reflection on the role of paper by Marco Frascari, Peter Galison’s discourse on the image and logic traditions, the role of the black screen and white paper by Mark Wigley, and an exploration on the geometry and numeric by Mario Carpo.

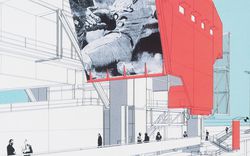

Following the seminar was a more specific research project by Greg Lynn entitled the Embryological House. The ambition of the investigation was to rethink the notion of the manufactured house, from the modernist idea of a form based on parts and modules, and create a new concept, based on unlimited iterations deriving from a “primitive form.” The Embryological House was also a landmark within the CCA Collection as it was one of the first cases where we had to fully engage in working with digital material.

What Next?

Archaeology of the Digital is the first of a series of exhibitions, publications, and seminars being developed by the CCA to take place over the next few years. It is an incessant collaborative project with the instrumental curatorial contribution of Greg Lynn and the work and projects of a number of architects and designers. These professionals’ steady commitment to this project has been and will continue to be critical in defining the framework for CCA’s tasks ahead, and will certainly complement the investigation, interpretation and exhibition of their work.

Furthermore, Archaeology of the Digital is a transformative internal force for the CCA to rethink the approach and structure required to engage the challenges posed by digitally-produced and -stored material. It is a first step towards collecting and documenting digital material. Just as important, it is an imperative phase for the emergence of a process of cataloguing, preserving, storing and accessing digital records and related media for future researchers.

Like some works on media archaeology, ours is an effort in reading the new against the grain of the past; of constructing, as Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka suggest, alternate histories with often suppressed or neglected materials that do not necessarily point to the final results and where projects, even when never materialized, have important stories to tell.3

To be continued . . .

-

For further accounts on Pask and Price’s collaboration, see Stanley Mathews, “The Beginnings of the Fun Palace,” in From Agit-Prop to Free Space: The Architecture of Cedric Price (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007), 74–75. ↩

-

See Sanford Kwinter, “The Computational Fallacy,” Thresholds 26 (Spring 2003): 90–91. ↩

-

See the introduction to Wolfgang Ernst and Jussi Parikka, Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 8. ↩

Mirko Zardini is an architect, curator, and editor, and Director of the CCA. This text was first published in Archaeology of the Digital, a book we produced in 2013.