Exhibition Machines, Ghosts

Greg Barton on Ábalos & Herreros’s lecture-machines

In the archives of Ábalos & Herreros at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, a document outlining the concept for the Third Biennial of Spanish Architecture and Urbanism in 1996–1997 begins with a direct question that the discipline continually confronts: “How to exhibit architecture?”1 The proposal goes on to express dissatisfaction with both traditional and hyper-technological exhibitions, asking how architecture can be communicated and what aspects of it are transmissible.

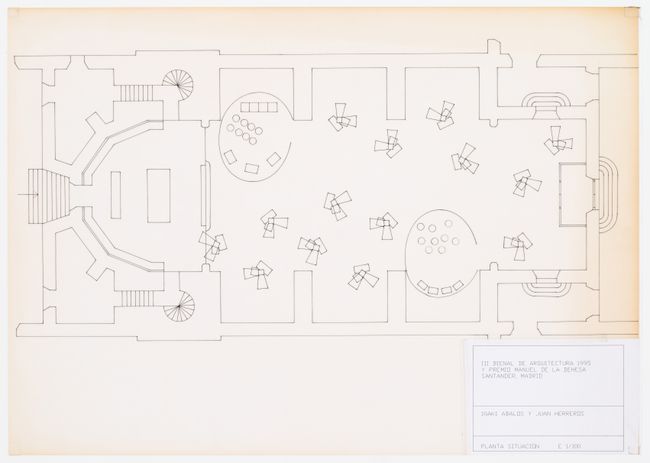

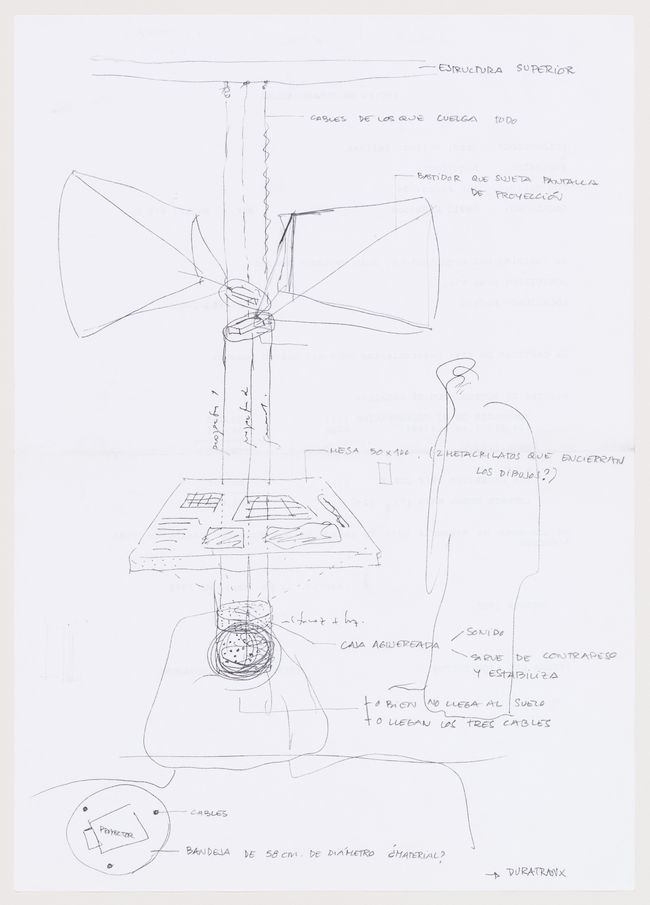

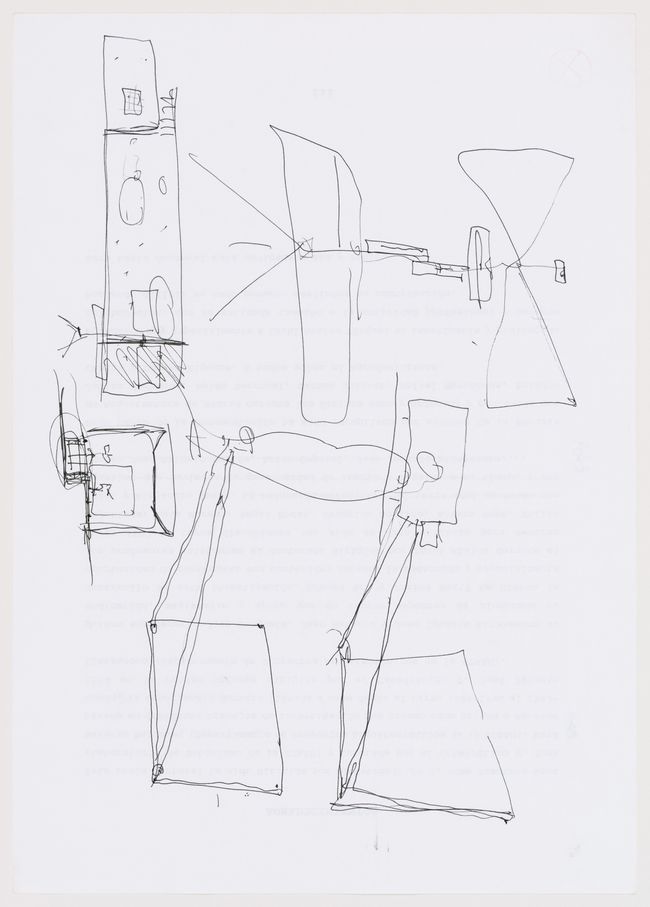

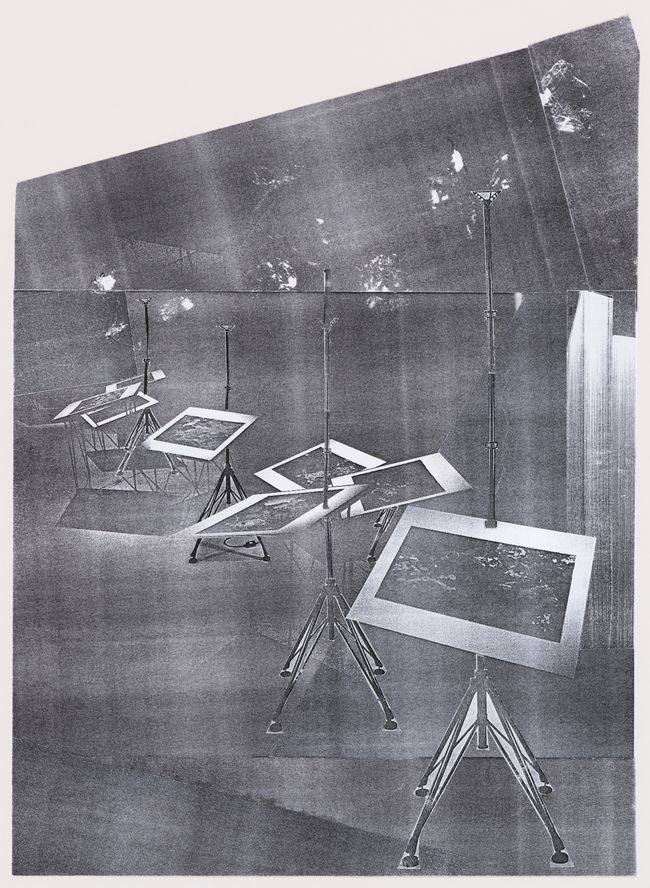

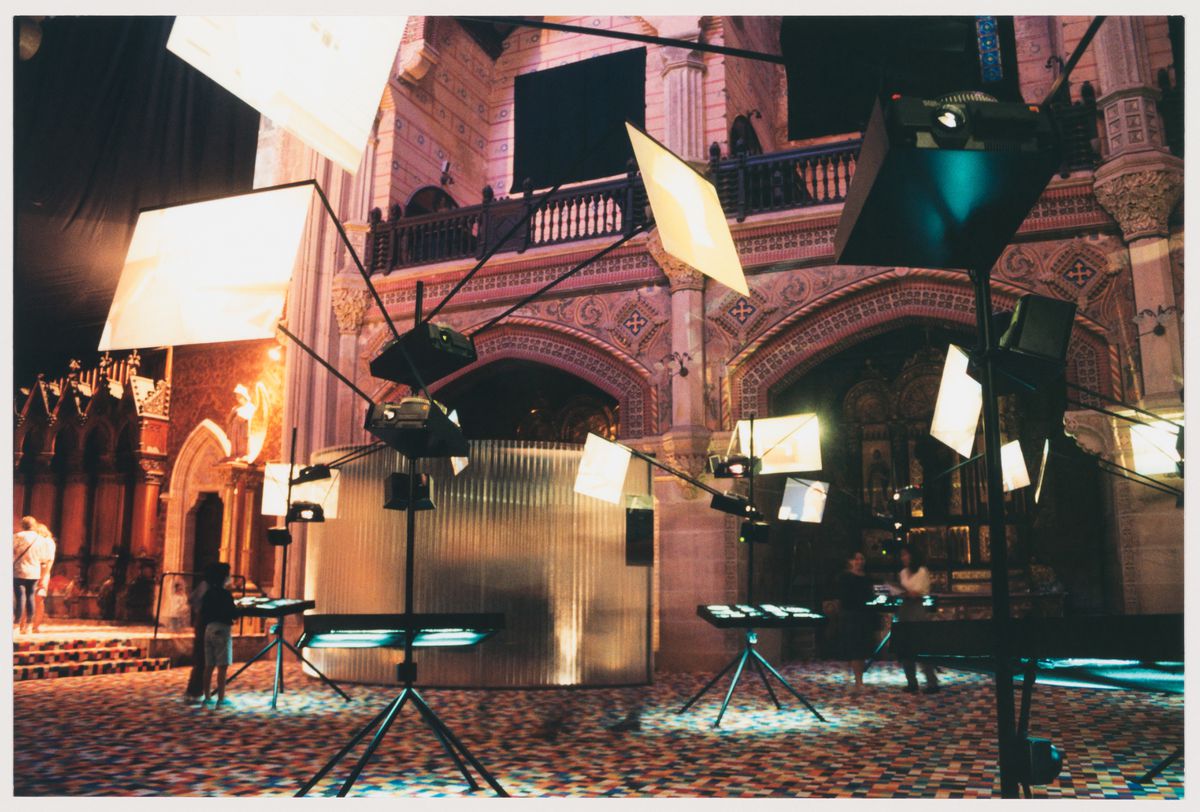

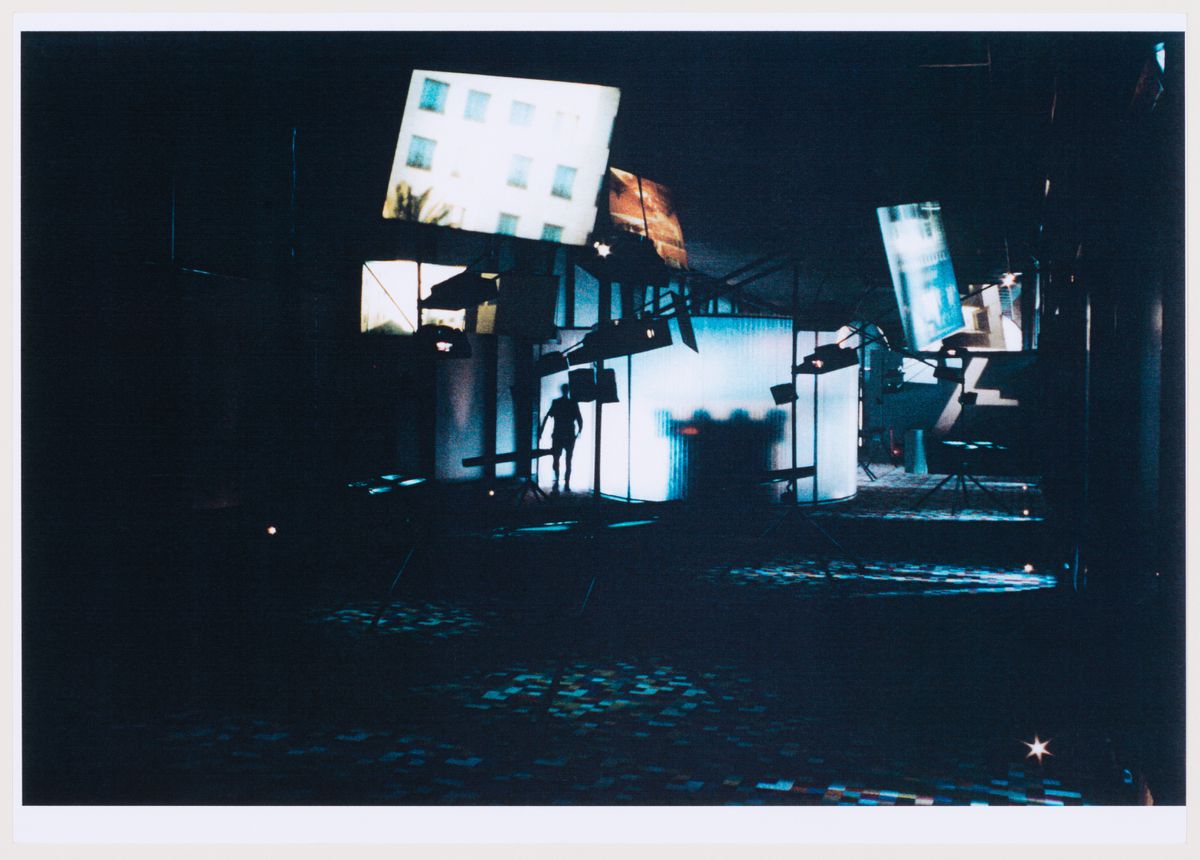

For Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros in the mid-1990s, the most effective answer was an apparently traditional one: the form of a lecture with slides, which involves “voice and light, creating a state of attention and a fleeting illusion able to convey the emotion of reality.” The lecture, in which an architect stands at the front of the room and speaks to images, has long been an important way to explicate buildings and ideas. But Ábalos & Herreros’s design replaces the architect with a machine: a device with two speakers that plays audio recordings, read by male and female voice actors, and two slide carousels that project photographs of the buildings onto protruding screens, attached to a pole mounted on a quadropod and stabilized at waist-level by a lightbox-table with duratrans of text and drawings elaborating each project. The entire contraption was equipped with motion sensors, activated by the visitor’s presence. In addition to fourteen such machines, the exhibition design included two other components: translucent, plastic ellipsoid enclosures housing scale models and videos and a commercial carpet designed by Gerhard Richter to tie the room together.2 The show was installed in a church in Comillas in 1996 and a ministry hall in Madrid in 1997.

-

Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros, “Exposicion Bienal. Concepto” (1995). ↩

-

This carpet was recreated by SO-IL for the exhibition Landscapes of the Hyperreal. ↩

Ábalos & Herreros, III Bienal Arquitectura Española, Comillas and Madrid, Spain, 1995. Graphite on paper. ARCH273100, Ábalos & Herreros fonds, CCA Collection. © Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros

Ábalos & Herreros referred to the lecture-machine as an automaton. This anthropomorphization encourages one to imagine twenty-eight architects standing in an exhibition space, each expounding with his or her own slide projector, collectively producing a scene of overlapping voices and images. The strength of the audiovisual machine lies in its ability, like an automaton, to elicit a feeling of magic or wonder from a rudimentary device designed to perform a specific function, in this case, a lecture. The machine was composed of conventional off-the-shelf parts combined in a creative fashion. Importantly, Ábalos & Herreros’s approach to designing the machine is similar to the strategies they developed in their building projects.

As opposed to traditional museological representations of architecture, which in the words of Ábalos & Herreros tend to be either “books on walls, absolutely two-dimensional, or just a collection of models and drawings presented in a fetishistic way,” the machines create a novel architectural effect.1 They are “capable of constructing, on the basis of their relative position, scale and variety, another spatial experience, one that would invite us to walk around, look, hear, study, choose or stumble upon some more specialized space.”2 Aside from being connected to a power source, the machine remains autonomous in its placement independent of context or walls. The contraption was not always free-standing, however. An early sketch shows how the two slide projectors and table might be suspended from floor-to-ceiling cables, and an evocative collage introduces the quadropod-with-table populating a darkened space. In marrying the two components as a self- contained entity, the new unit gains a maximum degree of mobility and flexibility in its placement and its potential relationships.

It is possible here to draw a comparison to the interest of Ábalos & Herreros in technological developments of the office workstation and open-plan workplace. In Tower and Office: From Modernist Theory to Contemporary Practice (originally published in 1992 as Técnica y arquitectura en la ciudad contemporánea 1950–1990), the duo conflates the “office landscape” and the city by reading office configurations as urban schemes. They identify a key shift in the approach to the design of workspace in the second half of the twentieth century. The introduction in the 1960s of new organizational philosophies, mobile furnishings, and uniform energy services disrupted the 1950s modernist offices based on rigid geometric modules and hierarchical private subdivisions, leading to more organic spatial arrangements akin to the proposals of Team 10 affiliates. In the 1970s, computerization and telecommunication technologies minimized the importance of physical contiguity; networks of information further challenged the building’s program and typology. Like an open office plan, the 1996–1997 Biennial avoided interior partitions and opted to standardize and democratize its individual projects, bundling functions together and fully embracing simulation to plunge viewers into a media environment of images. However, the exhibition’s virtual space relied on the visitor’s body in order to transmit its content and generate a condition of unexpected moments and juxtapositions, “each time [constructing] a different visual and acoustical experience, both personal and individual, thereby implicating subject and objects.”1

-

Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros, Áreas de impunidad | Areas of Impunity (Barcelona: Actar, 1997), 282. ↩

For the 2015 exhibition Industrial Architecture at the CCA, part of Out of the Box: Ábalos & Herreros, OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen recreated the lecture-machine in the gallery in order to display slides from the archive, which Ábalos & Herreros used for research, teaching and publication. Geers and Van Severen studied with Ábalos & Herreros in Madrid in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Therefore the replica, displaying materials they themselves encountered as students, acts as a silent lecture by their former professors. Although the idea of re-enactment is increasingly common in art and curatorial practice, the reconstruction of past architectural exhibitions is surprisingly infrequent.1 The reflexive act of restaging foregrounds the exhibition’s role as a mediating mode of address. Moreover, the reconstitution of innovative display techniques allows for a reassessment of the original’s aesthetics and affect from a contemporaneous perspective—a practice that is especially valuable to architecture as a spatial discipline.

In Industrial Architecture, the replica acted as an echo of the Biennial machines; it lacked the original’s interactive audio components and lightbox, existing as a mute, ghostly apparition. The restaged element, unaccompanied by documentation of its referents, exists as a partial memory, signalling the slippage between past and present inherent in exhibition-making. Extant material and temporal gaps characterize Geers and Van Severen’s encounter with the archives and define the speculative research that is at the heart of the CCA’s Out of the Box project.

The audiovisual machine remains a potent instance of scenography that has numerous lessons for today. Industrial Architecture opens up the performative possibilities of re-enactment as a means of engaging architectural projects and exhibitions. Ideally, this is a pleasure, as Ábalos & Herreros explain of the Biennial, “producing a complete re-description of reality, forcing a dialogue to be struck between one’s memory and new ideas, causing architecture to appear as a moment’s hesitation, as uncertainty, as a question rather than an affirmation.”2

-

Notable architectural examples include Archigram’s slide show opera (1972) and Arata Isozaki’s “Electric Labyrinth” (1968), restaged by various institutions in the 1990s and 2000s, as well as exhibitions like The International Style: exhibition 15 and the Museum of Modern Art (1992) and Environments and Counter Environments. ‘Italy: The New Domestic Landscape,’ MoMA 1972 (2013), both presented at Columbia University’s architecture gallery. ↩

-

Iñaki Ábalos and Juan Herreros, “Algunas preocupaciones sobre la technología” / “III Bienal de Arquitectura Española,” a+t 9 (1997): 124-125. ↩

Greg Barton wrote this text as a 2014-2015 Curatorial Intern. An online finding aid for the Ábalos & Herreros fonds is available.