On flatpack furniture and .zip folders

Simone Niquille considers the simulation of domestic space

This story begins in 2006, the year furniture company IKEA featured a digital rendering of a product for the first time in its globally distributed print catalogue: an image of the ubiquitous Bertil chair in birch. Until then, all products and scenes depicted in the catalogue’s pages were painstakingly staged and photographed. As product colours, choice of appliances, and object arrangements differ depending on the country of publication, some room setups needed to be photographed multiple times for the various versions. Staging the catalogue virtually simplified the global versioning for IKEA’s in-house communications team—switching a bathtub for a shower would now be a matter of a click rather than an entire scene rebuild. This transition to rendered images was a logical step for efficiency, yet it depended on the ability of computer-generated imagery to go unnoticed. The publication of the digital Bertil proved to be a success: the rendered image went unnoticed. Customers looking through the IKEA catalogue could only see the catalogue, not the process behind its creation.

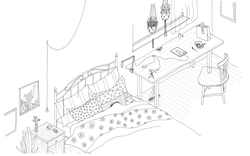

Computer generated imagery (CGI) has come a long way from its jagged beginning. While early computer graphics were noticeably comprised of polygonal structures, the technology’s current capabilities can produce images indistinguishable from photography. Photorealistic renders, or constructed images that simulate reality to the point of deception, are used in architectural visualization as much as in Hollywood special effects. Since modeling the Bertil chair in 2006, IKEA has amassed a digital library of approximately thirty-seven thousand products, ten thousand materials, and twelve thousand textures. In 2016, some of IKEA’s brochures featured 95% 3D graphics, some entirely digital renders, while others a composite of photography and 3D graphics.1 Whether photographed or rendered, IKEA is careful to make its catalogue scenes look lived-in, as if they document someone’s life rather than simply displaying a product. For this purpose, its digital library includes “life-assets” such as bananas, cats, and plants that are sprinkled into the digital product setups. IKEA’s challenge in transitioning its visual communication to digital imagery was to do so without it being apparent to the customer. Ideally, it would produce mundane CGI: everyday images that do not pose any questions. Documentation rather than installation; of course someone lives here.

-

“IKEA,” immerseuk.org, https://www.immerseuk.org/case-study/ikea/. ↩

Dawn, all is asleep. The apartment humming of charging batteries and the faint beep of a completed cleaning cycle.

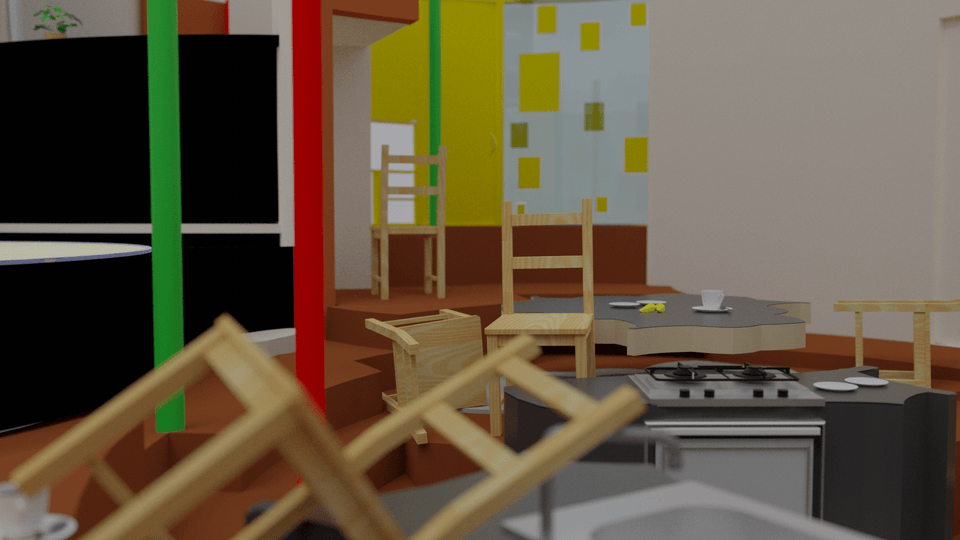

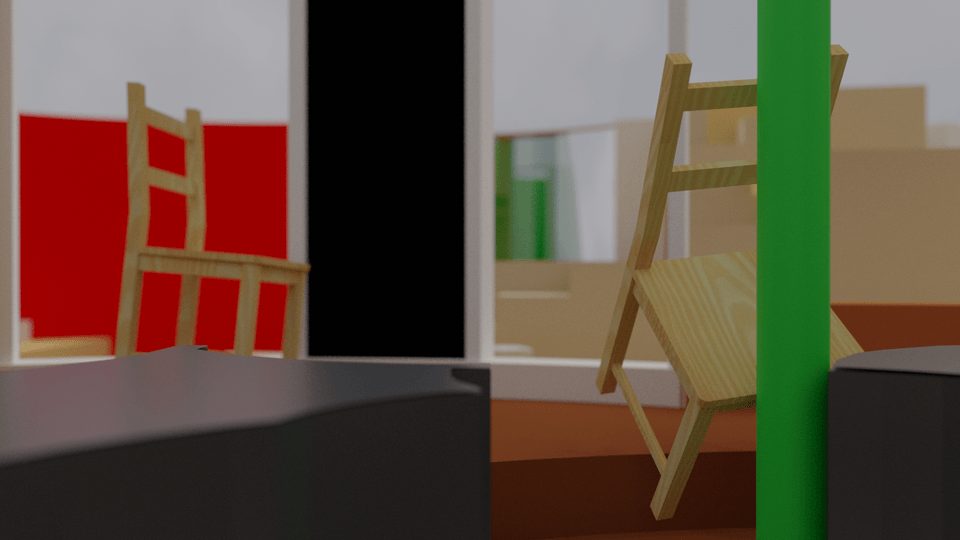

Simone Niquille, in collaboration with ST Luk of the Reversible Destiny Foundation, IKEA Bertil chair at the Arakawa + Gins Shidami apartment (2021) © Simone Niquille / Technoflesh (2021). Shidami apartment project © Arakawa + Gins

Living with computer vision

Besides IKEA’s global marketing needs, large datasets for 3D models are also essential in the field of computer vision. To train a camera to see, datasets containing examples of what the computer vision is intended to recognize are assembled. In the case of domestic robots—which are less like characters from The Jetsons and instead autonomous vacuum cleaners, laundry assistants, or lawn mowers—these datasets are indoor scenes, rendered from a huge repository of 3D products and spaces, similar to IKEA’s digital library. These robots’ actions are not magical but codified. Their bodies are not enchanted but delegated by an on/off switch. When Boston Dynamic’s Spot, a four-legged robot previously announced as a home and office assistant, was adopted by law enforcement in New York City and renamed Digidog, instruction manuals on how to remove the robot’s battery pack circulated the internet as a form of resistance. These automated machines are not intelligent, but rather trained to complete specific tasks. The huge amount of data needed to develop a working system can be overwhelming to process for a human mind and be confused to represent at least some of life’s layered complexity. This data needs to be recorded or made and as such is limited not necessarily in its amount, but in its diversity.

The challenge in creating these training datasets is to source large amounts of specific data. In the case of domestic robots, that data seeks to represent the indoor spaces of future customers. A vacuum cleaner might be equipped with computer vision to recognize what space it is in and estimate the type of floor and dust it needs to clean. However, iRobot’s popular Roomba vacuum cleaner, originally outfitted with a laser to measure its distance from objects, has long struggled to recognize dog poop. Instead of navigating around it, social media holds many accounts of a Roomba rolling over it and spreading the mess all over the home. The result is obviously quite the opposite of cleaning. Despite the growing application of “smart” technology in the home, it remains an intimate and private space. The cartoon Rick & Morty ominously foresees a transparent future when Morty searches for Rick, only hearing his voice: “Is everything a camera now?!” The scene ends with Rick having turned into a pickle rather than there being omnipresent vision.

The Dyson Robotics Lab at Imperial College London has published two datasets of indoor scenes specifically for the training of domestic computer vision. While they are one of several academic research labs invested in computer vision, it is interesting to simply compare their two successive datasets from 2016 and 2018. Supported by the home appliance company Dyson, the lab’s aim is to develop computer vision significantly enough to implement it into the brand’s future products. Mike Aldred, the company’s head of robotics, voiced his wish for an automated future as such: “I’d love for people not to be able to tell me what their robot looks like. So they come home and the floors are clean and they don’t know what it looks like because it just happened when they’re not there.”1 This concept is reminiscent of the enchanted household items in Disney’s animated fairy tale Beauty and the Beast: largely invisible to the human inhabitants, the busy teacup, pot, and candleholder organize daily chores so that the main character can devote herself to her dating life. But how do these items gain a waking life?

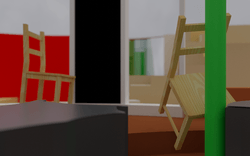

The first of these datasets by the Dyson Robotics Lab, SceneNet RGB-D, contains rendered indoor scenes, assembled with thousands of 3D models gathered online, mostly from the popular SketchUp warehouse. This online repository hosts models, created by individuals and companies alike, for use in the CAD software SketchUp. The dataset divides these models into categories of domestic bliss—chairs, beds, etc.—but upon closer inspection of the data, the challenge of assembling a domestic dataset becomes very clear. The category for chair holds very ubiquitous models made of four legs and a backrest, but alongside these it also contains an electric chair, a wheelchair, and a gynecologist’s chair. Next to all the data that is in the wrong place is the abundance of sitting types that are missing. The multitude of cultures and lifestyles that are not represented in the dataset’s understanding of sitting is staggering.

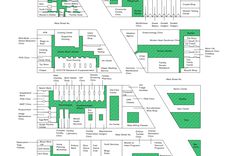

The second of these datasets, InteriorNet, is an update in scale, variability, and file resolution. It is a self-described “mega-scale multi-sensor photo-realistic Indoor Scene Dataset”2 comprised of around 1 million CAD models of furniture and 22 million interior layouts. To achieve this volume of material, the academic researchers paired up with Kujiale, a Chinese product visualization and interior design company. The lab’s partnership with a company that had an existing 3D asset library as part of their business model was a departure from the researcher’s methods of assembling 3D files themselves by scraping online repositories or purchasing asset libraries sold via game engines. Through this arrangement, the researchers at the Dyson Robotics lab were able to use Kujiale’s 3D assets to assemble the InteriorNet dataset. Kujiale’s 3D asset library is integral to its product: an online interface to design one’s own home. The company’s founders recognized the middle-class construction boom in China as a need for accessible 3D planning and set up the company in 2011.3 Its catalogue of floor plans, products, and materials are offered as part of fast mock-up tools for architects, interior designers, or homeowners. Once a design is finished with the drag and drop interface, it can be viewed in a virtual first-person walkthrough or rendered as single images. To facilitate this functionality, Kujiale had to create a large library of 3D assets, similar to IKEA. This library is what the researchers of InteriorNet were keen on accessing as their training dataset. InteriorNet’s accompanying research paper notes that all models obtained through the Kujiale partnership have been used in real-world production—a possible attempt to guarantee the 3D model’s realism, as if to assure: these products exist somewhere. The map is the territory.

-

James Vincent, “Why Dyson is investing in AI and robotics to make better vacuum cleaners,” The Verge, March 14, 2017, https://www.theverge.com/2017/3/14/14920842/dyson-ai-robotics-future-interview-mike-aldred. ↩

-

Wenbin Li et al., “InteriorNet: Mega-scale Multi-sensor Photo-realistic Indoor Scenes Dataset,” ArXiv, 2018, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1809.00716.pdf ↩

-

Ben Sin, “This 3D Design App is Used by Millions of China’s House Builders, and Plans to Go Global,” Forbes, April 3, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/bensin/2018/04/03/how-three-chinese-entrepreneurs-built-a-software-that-helps-citizens-build-homes-from-the-ground-up/?sh=55980a3d1b5f. ↩

Dawn, all is asleep. The apartment humming of charging batteries and the faint beep of a completed cleaning cycle.

Simone Niquille, in collaboration with ST Luk of the Reversible Destiny Foundation, IKEA Bertil chair at the Arakawa + Gins Shidami apartment (2021) © Simone Niquille / Technoflesh (2021). Shidami apartment project © Arakawa + Gins

Daily life noise

IKEA and Kujiale are not alone in creating large 3D asset libraries. Other online retailers, such as Germany’s Otto and eCommerce company Wayfair1 have been transitioning to CGI imagery to populate their online retail interfaces. The impossibility of organizing photoshoots due to the COVID-19 pandemic has only further accelerated this shift. Even ice cream company Ben & Jerry’s has made the switch to “virtual photography,” 100% rendered imagery.2

These companies share a need to overcome physical limitations to sell their products. In Ben & Jerry’s case it is the want to home-deliver ice cream while shops are closed; for IKEA it is to avoid building costly and time-consuming catalogue scenes; for Kujiale it is to aid in selling homes before they are built. The resulting 3D asset libraries are a marketing by-product and are driven by demand. Yet, these corporations’ new mission to create huge 3D asset libraries of their products, at a speed and quality unattainable with non-commercial budgets and computing resources, aligns with computer vision’s hunger for more high-resolution synthetic data.

Justifying his donation to Imperial College London, Sir James Dyson verbalized computer vision’s quest for data on people’s homes: “My generation believed that the world would be overrun by robots by the year 2014. We have the mechanical and software capabilities, but we still lack understanding—machines that see and think in the way that we do. Mastering this will make our lives easier and lead to previously unthinkable technologies.”3 Aggregating enough training data is crucial in creating this “understanding.” Sir Dyson refers to machines that imitate “us” and “will make our lives easier.” To whom is he referring? There is no global definition of domesticity, of home. Whose lives will be eased, whose will be imitated, and whose will be excluded?

-

Matt Ciarletto, “Building a Living 3D Rendering Platform,” Wayfair, October 11, 2017, https://www.aboutwayfair.com/2017/10/building-a-living-3d-rendering-platform/. ↩

-

Gail Cummings, “How Ben & Jerry’s is leading the virtual photography revolution,” Adobe, https://business.adobe.com/customer-success-stories/ben-and-jerrys-case-study.html. ↩

-

Colin Smith, “Dyson and Imperial to develop next generation robots at new centre,” Imperial College London, Februrary 20, 2014, https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/142147/dyson-imperial-develop-next-generation-robots/. ↩

Dawn, all is asleep. The apartment humming of charging batteries and the faint beep of a completed cleaning cycle.

Simone Niquille, in collaboration with ST Luk of the Reversible Destiny Foundation, IKEA Bertil chair at the Arakawa + Gins Shidami apartment (2021) © Simone Niquille / Technoflesh (2021). Shidami apartment project © Arakawa + Gins

Training datasets play a crucial role in defining how a computer vision system “sees” the world. It recognizes based on previously digested information. In a scenario where corporate 3D asset libraries become training datasets for computer vision, is a home only a home if it corresponds to the IKEA catalogue, the Wayfair inventory? Does domesticity, to computer vision, only start around 2006 when the synthetic Bertil chair was created? Some of us have these products in our homes, but our homes are not defined by them. Take for example the many do-it-yourself instructions through which consumers “hack” IKEA products into novel reconfigurations—what happens to products once they arrive at someone’s house is a private mystery. While the SceneNet RGB-D dataset accidentally included the creations of hobbyists, independent design studios, and family members and friends that built things for each other by scraping the SketchUp warehouse, InteriorNet got rid of all the wonderful, wonky creations people made for one another. Images produced to market a product are not synonymous with how people choose to live. What are the consequences on people’s homes if the most intimate living spaces are defined by the products they contain, rather than their culture, the beings they shelter, the rhythms they provide?

In the InteriorNet paper, the researchers note that “daily life noise”1 has been added to the indoor scenes to convey realism. This noise, in the language of the authors, is the fairy dust of which life is made. Notes on the door, a moldy yogurt in the fridge, a snoozed alarm clock, naps in places that are not the bed. There are many types of homes defined by their inhabitants and their layered, evolving identities. Domestic life is not easily coded and indexed, regardless of computer vision’s requirements. In the realm of the home, computer vision is mainly developed for purposes of hygiene and control: dreams of robots that autonomously—and most importantly, invisibly—vacuum the floors, load the dishwasher, weed the garden, water the plants, greet homecoming family members, open the front door for package deliveries. Ideally these robots would take care of, maintain, and manage the home for its inhabitants. It is inviting to place the discrimination of computer vision with the lack of diversity in the training dataset. A quote by musician and poet Laurie Anderson’s meditation teacher comes to mind: “If you think technology will solve your problems, you don’t understand technology—and you don’t understand your problems.”2 What problem is domestic computer vision a solution to? Is it one of increased workload that makes it impossible to also maintain a household? A shift in how society organizes and values time? Or is it a deeper systemic continuation of outsourcing care work and maintenance for little pay and so that it remains out of sight? In other words: the training dataset might not be the problem, but reflects the world for whom it is being built.

-

Li et al., “InteriorNet.” ↩

-

Bruce Sterling, “Laurie Anderson, maching learning artist-in-residence,” Wired, March 9, 2020, https://www.wired.com/beyond-the-beyond/2020/03/laurie-anderson-machine-learning-artist-residence/. ↩

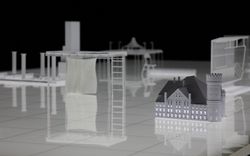

Accompanying this essay is a series of images showing the IKEA Bertil chair trying to find its place in Arakawa+Gins’s Shidami apartment project, the first of their experiments in constructing an inhabitable residential home that was completed in 2005. Bertil takes on the role of standardized object in contrast to Arakawa+Gins’ body enhancing and life conscious architecture. Itself not enhanced with seeing technology, the Bertil chair is a token for the synthetic world future domestic robots are training to navigate. These images are part of an ongoing research project into 3D model archives, computer vision training datasets and the definition of the home, done in collaboration with ST Luk of the Reversible Destiny Foundation. The renderings are created using research materials and information from the RDF digital archives.