Toys Shape Minds no. 2

Text by Daria Der Kaloustian

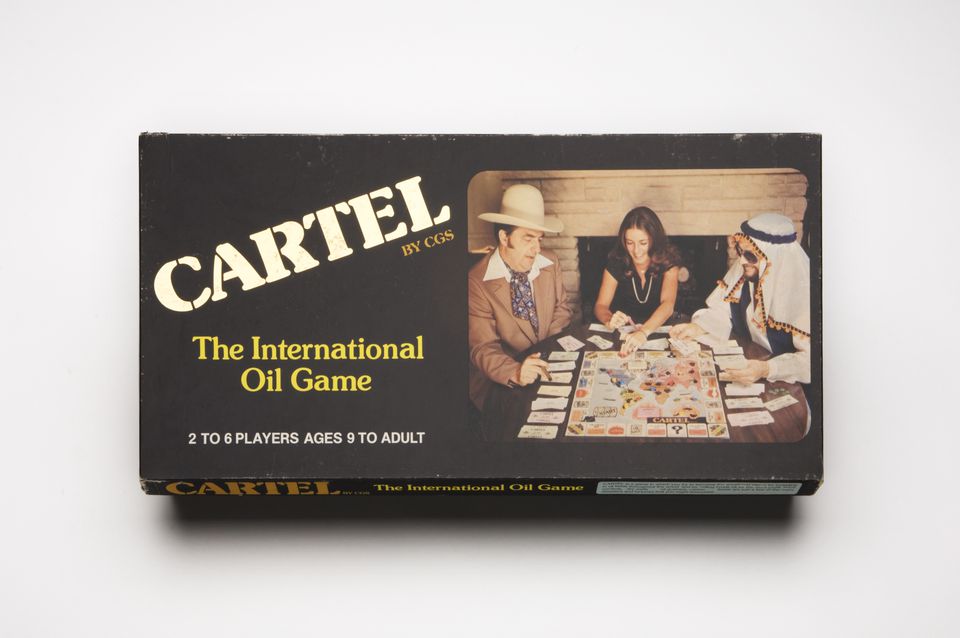

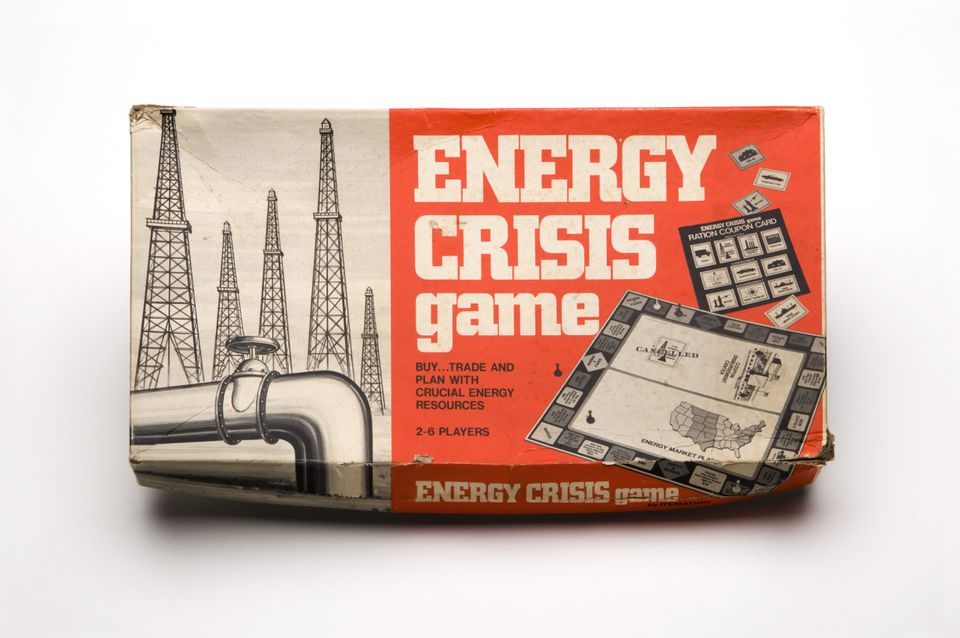

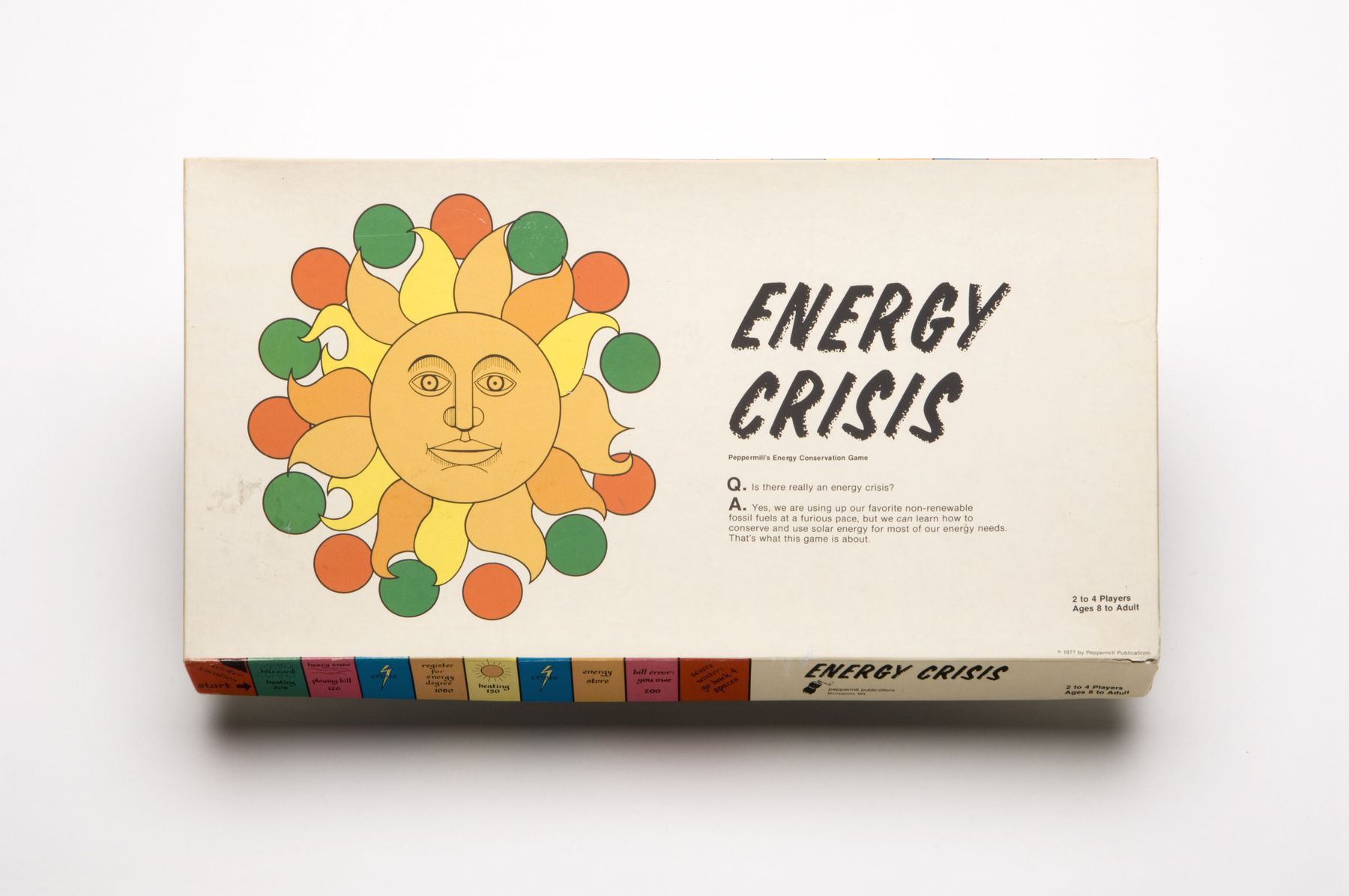

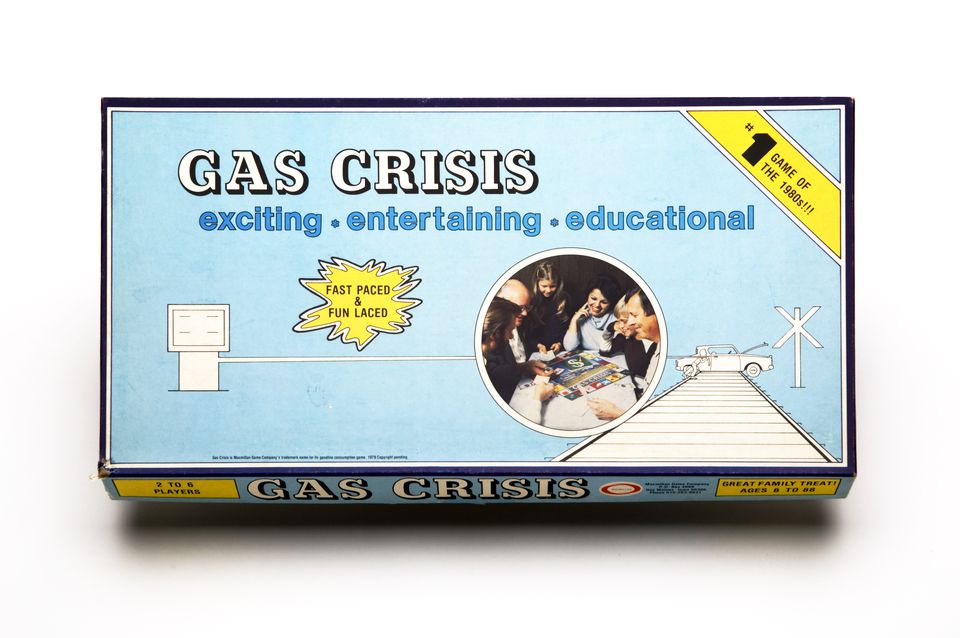

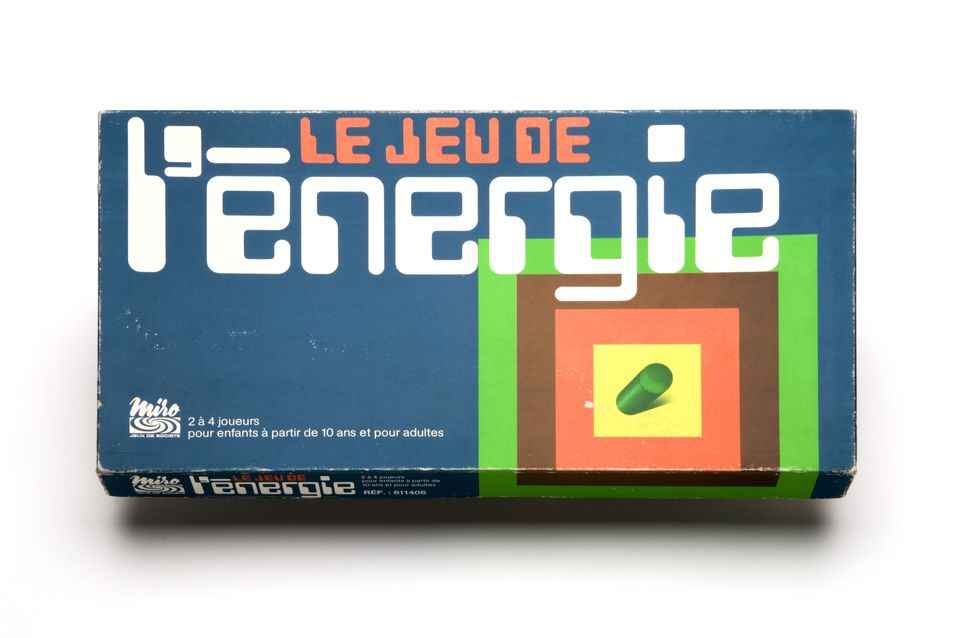

From 1973 to the mid 1980s, energy issues—the scarcity of oil, power struggles between producer and consumer nations, and the search for alternative energy sources—were a “hot button” topic. Games manufacturers took advantage of the situation to create and market various board games dealing with these issues and how they were unfolding.

The games tended to view oil as a source of power and wealth, as their names clearly indicate—Conquering Oil, King Oil, Black Gold, Oil Power. Players would get involved in exploration, buying oil, and resource exploitation. The aim of the game was inevitably to get rich: in Petropolis, the winner was the player who ended up owning the most oil wells, in North Sea Oil, the person who had accumulated the most oil dollars. Generally, these games were modelled on Monopoly, whose rules offer a close analogy to the workings of capitalism, but their packaging used images related to the oil industry.

Another category of games was geared to the dual concept of war/oil. Players were asked to simulate military manoeuvres aimed at clearing the way to taking over or protecting oil-producing nations. An example of this type is Oil War.

A third group, including Alaska Pipeline and Energy Crisis Game, presented strategies for managing an oil crisis. The purpose here was more educational, in that players had to take into consideration the demand for oil, and its varied uses, in order to plan the nation’s overall oil consumption.

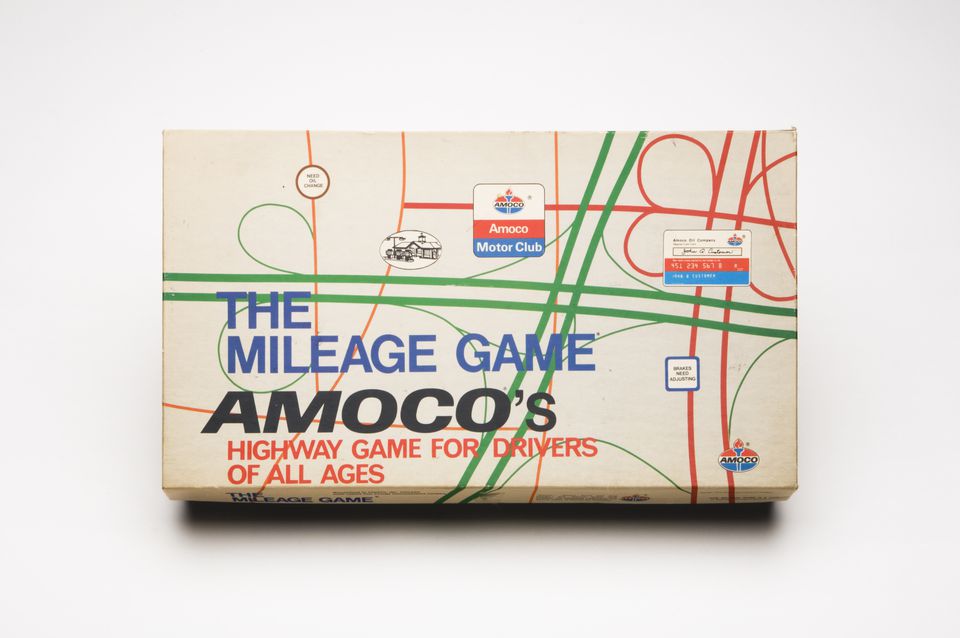

Historians and researchers often see games as a source of information about the customs and concerns of a given era. The way games work, and their meanings and goals, are linked to the social context in which they are invented and popularized. Indeed, some consider games to be a primeval part of civilization.1 Towards the end of the 1970s, as energy conservation and the search for alternative sources became priorities, other games appeared on the market that took up these problems and gave players the chance to simulate solutions to them. In The Mileage Game, the winning player had to cover the greatest possible distance while wasting a minimum of energy; and Energy Quest involved research into and acquisition of a variety of new forms of energy.

-

Roger Callois, “Préface,” in Jeux et sports, Pléiade Encyclopédie, no. 23 (Paris: Gallimard, 1991), 8–9. ↩

This text and the games mentioned originally appeared in Sorry, Out of Gas, a book published in 2007 to accompany an exhibition of the same name. Our collection holds a significant number of toys and games related to architecture and society.