Bungalow Bliss

Here, we present several perspectives on the bungalow, a building type with its own proper history and range of appearances.

Toys Shape Minds no. 3

Text by Rosemary Haddad

Bumpalow House and Bumpalow Cottage are both from a set of six “easy builder” toys which together form a set called the Bumpalow Town, produced by the Milton Bradley Company. Established in 1960, the company manufactured thousands of games, puzzles, and construction toys: building blocks, a Swiss Cottage, a Texas Ranch, a New England Homestead. Its founder, Milton Bradley, championed the Kindergarten movement in America and manufactured many of the educational toys used in its programs. The company purchased McLoughlin Bros. in 1920, and was itself taken over by Hasbro Industries in 1984.

The Bumpalow Cottage was displayed in Dream Houses, Toy Homes, one in a series of exhibitions we developed during the 1990s exploring the relationship between toys and architecture. This text originally appeared in the accompanying publication. We have a significant number of toys and games in our collection.

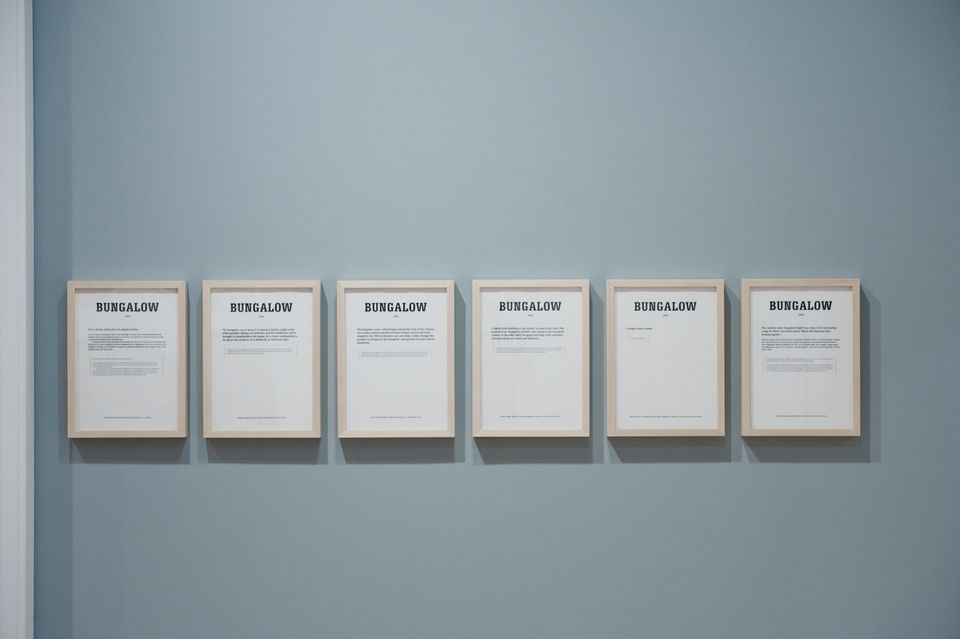

A Dictionary with Only One Word

Or, a biography of the bungalow

- 1855

- BÁNGLÁ, corruptly, BUNGALOW, Beng. (probably from Banga, Bengal) A thatched cottage, such as is usually occupied by Europeans in the provinces or in military cantonments.1

-

H. H. Wilson, A Glossary of Judicial and Revenue Terms and of Useful Words Occurring in Official Documents Relating to the Administration of the Government of British India (London: W.H. Allen and Co., 1855), 59. ↩

- 1886

- BU’NGALOW, a species of rural villa or house, so called in India.

Bungalows which form the residence of Europeans, are of all sizes and styles, according to the taste and wealth of the owner. Some are of two stories, but more usually they consist of only a ground-floor, and are invariably surrounded with a verandah, the roof of which affords a shelter from the sun. In the chief cities of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay some of the bungalows are really palatial residences, while in the mofussil they are of more moderate pretensions. In general, they are provided with exterior offices, to accommodate the large retinue of domestics common in Indian life. Besides these private bungalows, there are military bungalows on a large scale for accommodating soldiers in cantonments ; likewise public bungalows, maintained by government for the accommodation of travellers, and in which seem to be blended the characters of an English road-side inn and an eastern caravanserai. These bungalows, though they vary greatly in actual comfort, are all on the same plan. They are quadrangular in shape, one story high, with high peaked roofs, thatched or tiled, projecting so as to form porticos and verandahs.1

-

Chambers’s Encyclopædia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge for the People, volume II (London: W. & R. Chambers, 1886), 425–426. ↩

- 1891

- And now for a word about Bungalows and Bungalow Houses. What is a Bungalow?

Our imagination, if we have not travelled beyond Europe, immediately transports us to India, with its glaring sun and arid soil, to low, squat, rambling, one-storied houses, with wide verandahs, latticed windows, flat roofs, and with every conceivable arrangement to keep out the scorching rays of the sun and to promote as much coolness as possible. Or else we think of some rude settlement in one of our colonies, where the houses or huts, built of logs of wood hewn from the tree, and with shingle roofs, give us an impression, as it were, of “roughing it”.

But this is not the kind of Bungalow suitable for our climate, neither is it necessary that it should be a one-storied building or a country cottage. A cottage is a little house in the country, but a Bungalow is a little country house—a homely, cosy little place, with verandahs and balconies, and the plan so arranged as to ensure complete comfort, with a feeling of rusticity and ease.1

-

Robert Alexander Briggs, “Preface,” in Bungalows and Country Residences: A Series of Designs, and Examples of Executed Works (London: B.T. Batsford, 1891). ↩

- 1903

- The most usual class of house occupied by Europeans in the

interior of India ; being on one story and covered with a pyramidal roof, which in the normal bungalow is of thatch, but may be of tiles without impairing its title to be called a bungalow…

A bungalow may also be a small building of the type which we have described, but of temporary material, in a garden on a terraced roof for sleeping in, &c., &c. The word has also been adopted by the French in the East, and by Europeans generally in Ceylon, China, Japan, and the coast of Africa…

It is to be remembered that in Hindustan proper the adjective ‘ of or belonging to Bengal ’ is constantly pronounced as banga˘la¯ or bangla¯. Thus, one of the eras used in E. India is distinguished as the Bangla¯ era. The probability is that, when Europeans began to build houses of this character in Behar and Upper India, these were called Bangla¯ or ‘ Bengal-fashion ’ houses ; that the name was adopted by the Europeans themselves and their followers, and so was brought back to Bengal itself, as well as carried to other parts of India.1

-

Henry Yule, A. C. Burnell, and William Crooke, Hobson-Jobson: a Glossary of Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases : and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical, and Discursive (London: J. Murray, 1903), 128. ↩

- 1906

- There is nothing either affected or insincere about these little houses. They are neither consciously artistic nor consciously rustic. They are the simple and unconscious expression of the needs of their owners, and as such they can be credited with the best kind of architectural propriety. Nothing, indeed, could be more flimsy than their method of construction. Higher than two stories they do not soar.1

-

Frederick T. Hodgson, Practical Bungalows and Cottages for Town and Country (Chicago: F.J. Drake & Co., 1906), 34. ↩

- 1908

- The Bungalow is a tangible protest of modern life against the limitations and severities of humdrum existence. It is homey and comes near to that ideal you have seen in the dreamy shadows of night when lying restless on your couch you have yearned for a haven of rest. Maybe it has a wide, low, spreading roof, which sweeps down and forms a covering for the porch. It has a large healthy chimney, patios, with fountains, large verandas, good sized living and dining rooms, so arranged possibly that by the use of portable wood screens they may be partitioned off or thrown into one apartment.1

-

Radford’s Artistic Bungalows (Chicago: Radford Architectural Co., c. 1908), 3. ↩

- 1908

- Correctly speaking, the word “Bungalow” describes a one-story thatched or tiled house, with wide verandas on at least

three sides.

The word is of Anglo-Indian origin; and was first used to describe this type of building, so well known in India.

The adaptability of the bungalow form of dwelling to the requirements of families of moderate size has been realized by architects for many years, and the results achieved, particularly on the pacific Coast, where climatic conditions favor this type of house, have been satisfactory in a high degree.

Where a second story has been added the building loses its chief characteristics and cannot be truthfully designated as a bungalow. It becomes simply a cottage on bungalow lines.1

-

The American Architect and Building News 94 (19 August 1908): 63. ↩

- 1909

- It is a house reduced to its simplest form…

It never fails to harmonize with its surroundings, because its low broad proportions and absolute lack of ornamentation give it a character so natural and unaffected that it seems to sink into and blend with any landscape.

It may be built of any local material and with the aid of such help as local workmen can afford, so it is never expensive unless elaborated out of all kinship with its real character of a primitive dwelling. It is beautiful, because it is planned and built to meet simple needs in the simplest and most direct way…1

-

Gustav Stickley, Craftsman Homes (New York: Craftsman Pub. Co., c. 1909), 89. ↩

- 1916

- The bungalow, as we know it in America, had its origin in the mild equitable climate of California and the Southwest, which brought to homebuilders the desire for a closer relationship to the great out-of-doors. It is distinctly an American idea.1

-

Building a Bungalow (New York: The Atlas Portland Cement Company, c. 1916), 3. ↩

- 1926

- The bungalow craze, which began around the turn of the century, was a more radical reaction oriented toward nature and rustic simplicity; by 1926 its features are only dimly visible, though the porches so integral to the bungalow concept have become almost ubiquitous.1

-

“Publisher’s note,” in Honor Bilt Modern Homes (Chicago: Sears, Roebuck & Co., 1926). ↩

- 1942

- The average New Zealand bungalow, the product of the land speculator and the builder, is the typical home of a large percentage of the population.

Built usually in wood with a low pitched corrugated iron roof, its main features are its restless roofline and its fussy windows, as a rule with a high glass line and traces of Art Nouveau still lingering in the fanlights. The plan is usually neat, providing four or five rooms and with a large area of passage space, and is carefully oriented to the street frontage irrespective of sunlight, wind or privacy.1

-

H. Courtney Archer, “Architecture in New Zealand,” The Architectural Review 91 (March 1942): 54. ↩

- 1962

- A lightly built dwelling of one storey, as used in the East. The ironical term ‘bungaloid growths’ was coined in the twentieth century to describe badly designed and badly built suburban outcrops along our coasts and highways.1

-

Martin S. Briggs, Everyman’s Concise Encyclopaedia of Architecture (London: J.M. Dent, 1962), 62. ↩

- 1986

- The emotive term ‘bungalow blight’ has come in for increasing usage by those concerned about ribbon development and housing sprawl…

Why do so many urban workers want a rural base? Doubtless there are many reasons. Among them must surely be an anxiety to get away from all these social problems and pressures. Since Bungalow Bliss was published in 1971, over 100,000 people have bought a copy, surely underlining this anxiety. It is a source of great pleasure to me that I had the privilege of helping so many.1

-

Jack Fitszimons, “Preface,” in Bungalow Bliss, 8th ed. (Meath, Ireland: Kells Art Studios, 1986). ↩

These definitions were gathered for Journeys: How travelling fruit, ideas and buildings rearrange our environment, an exhibition and publication we produced in 2010.

Oh Bungalow, Born by the Bay of Bengal, You Conquered an Empire—and Then the World—Redefining Success Every Step of the Way!

Text by David Howes

The Seaside, England, 20 July 1969

Grey skies again today. I suppose one can’t expect too much in the way of fine weather at an English seaside resort in July. No one’s outside anyway, they’re all gathered around the television in the lounge, watching the Americans land on the moon. I’d rather sit in my room and watch the sea, watch the waves, always moving restlessly.

I was talking with Mrs. Rawlins in the lounge yesterday and she mentioned that she liked the name of our hotel, “The Bungalow Hotel.” “It’s so comfortable sounding,” she said. “It gives you a feeling of being at home and away on vacation at the same time.” It would give me a feeling of being at home too if it were anything like the bungalow in India I grew up in.

This place is just a three-storey building with William Morris wallpaper and 1930s furniture. The bungalow I grew up in in Lahore was a large, flat-roofed house with a wide veranda all around, set inside a walled compound filled with tropical plants. That was a real bungalow.

Read more

Of course, the original bungalows, I suppose, were the ones built by the native Indians for themselves before the English came. Those were thatched huts with an overhanging roof. That kind of house was called a bangala, meaning that it came from Bengal. The kind of bungalow my family lived in might have been based on native forms of architecture, but it was definitely a colonial creation: an Indian dwelling suitable for Englishmen.

Our bungalow was not a hut, but it was simple; one-storey with rooms for entertaining and rooms for sleeping. The surrounding compound provided space for a garden and for servants’ quarters but most importantly it allowed the house to be well-ventilated. In such a hot climate we were grateful for whatever breeze came our way. That’s why the house didn’t have hallways, to keep the air flowing from room to room. On particularly hot days the servants would be kept busy splashing water on the window and door screens to cool the air as it blew in. The screens were made from bamboo, which made the air passing through fragrant. When I think of our bungalow I remember that smell.

I spent much of my time playing on the veranda, watched over by my Ayah, as Indian nannies were called. I remember there was a snake that lived under that veranda and sometimes it would stretch out its shiny head and watch me, not do anything, just watch. My Ayah was scared that snake would bite me but I knew it wouldn’t, we lived on peaceful terms with each other. The shade provided by the veranda helped cool the air around the house and make it more bearable inside, but I always preferred to be outside anyway.

Inside the house was a piano, brought from England by my mother, which I was expected to play for half an hour every day. I think my mother thought of piano practice as a way to keep me from becoming too “native.” We lived surrounded by Indian servants, servants to clean, to cook, to garden, to fetch and carry… It didn’t bother me but I think it worried my parents. The number of servants combined with the open design of the bungalow didn’t really allow for much personal privacy. The heat seemed to bring us even closer together, all stewing, as it were, in the same hot, moist air. Whenever my parents met with their friends there would be talk about native revolts and uprisings. The feeling was that what happened outside in the city might happen inside in the bungalow. Each bungalow was imagined to be like a miniature empire, teeming with useful but potentially rebellious natives. Each bungalow had to be firmly ruled by its English master. How Father took that mission to heart!

Aside from the piano, the rest of our furniture consisted of Indian copies of copies of European originals. My mother held them in contempt for their “inferior workmanship,” but I liked their slightly crooked lines and unpolished finish. All the furniture in my grandmother’s house back in England seemed too smooth and shiny and slippery by contrast. Nothing to hold on to. As a special sign of high status we had a porcelain bathtub, imported from England as a gift from my father to my mother. Of course, it still had to be filled by servants carrying heated water in old kerosene tins brought all the way from the kitchen out back. The kitchen was separate from the house. It was located near the servants’ quarters, so that the bungalow wouldn’t be affected by the heat and odours of cooking.

My bedroom was at the back of the house. The walls were thin and I would lie in bed at night, feeling the breeze blowing in through the mosquito curtains and hearing my parents talking. My mother would come in wearing a floating, lacy dress and kiss me goodnight before going out to a party. Then I would fall asleep to the sound of the jackals calling somewhere outside the compound.

Though I thought of the bungalow as our property it was, in fact, rented. Almost all the homes occupied by the English were rented since people always expected to be moving on after a few years. Our bungalow was actually owned by a wealthy Indian businessman. It, like all the other bungalows in the city, had been built by local Indians using the same materials, brick and wood and clay tiles and lime plaster, and based on the same design. There seemed to be no point in catering to personal tastes when people came and went so frequently.

Mind you, there were bungalows and there were bungalows. Ours was a substantial house because Father was a senior administrator. A low-ranking official, however, might only have a little four-roomed bungalow with odds and ends for furnishings and walls that were whitewashed instead of painted. Though such distinctions mattered, they didn’t seem to matter quite as much in India as they would have in England. If you were short on cutlery for a party, for example, one of your guests might have a servant bring along an extra supply. No one really seemed to mind such things. I think there was a feeling among the English that they were all making do together in this foreign wilderness in which they happened to find themselves.

When I left India to go to school in England I thought I’d left bungalows behind forever. I knew they’d built bungalows for Europeans in Africa. “The Indian bungalow is the one perfect house for all tropical countries,” some supposed expert said. So up went the bungalows in the Gold Coast and in Nigeria and in Kenya. My brother Tom, who was a District Commissioner in Kenya, had a very handsome bungalow there, judging from the photos he sent us. It rested on pillars, which raised it a good eight feet off the ground to protect against the “exhalations of the earth” that were supposed to cause malarial fever. The way it was situated in that European enclave on the hill outside of town meant that it commanded a magnificent view, but Tom said it was for “hygienic” reasons, the supposed dangers of contagion from mixing with the native Africans in their village compounds, that he built there. He called his house “detached.”

Well, bungalows in Africa are one thing but I couldn’t see why anyone would want one in England, which must be one of the least tropical places in the world. The typical English home for me was my grandmother’s Victorian villa. It was very upright: three storeys plus an attic, ten foot ceilings, two sets of stairs (one for the servants). And it had so many divisions: the front hallway, the sitting room, the study, the basement, the upstairs hallways, the master bedroom, the girl’s bedroom, the boy’s bedroom, the nursery. Every room had its own fireplace, so there were lots of chimneys jutting out of the roof. And there was the gingerbread, so intricate, so much work to carve, so distinctive!

After the Great War, however, bungalows, or what were called bungalows, started springing up all over England. They had nothing to do with being good housing for a tropical climate. They were thought of as modern and economical. A bungalow was really just a small, square, one-storey house, like a child’s building block. You didn’t need any servants if you lived in a house like that. And, as I recall, servants were getting harder and harder to find before the War, never mind after. I suppose for many people, people like Mrs. Rawlins, who grew up in one of those boxy post-war bungalows, a bungalow does mean home. An English home at that, though not much of one. In India a bungalow was an important residence, it meant something to live in a bungalow there. It still does I understand. Here it just seems to mean cheap housing.

Though, now that I think about it, I realize there’s more to it than that. One of the reasons for the spread of bungalows in England was that they were seen as more natural, more informal and more open to the outdoors than traditional English housing, such as villas and townhouses. Just as life in India could feel more informal and more natural than life back home. I suppose people wanted some of that in England. That’s why bungalows became so popular as vacation homes. It was supposed to be the free and easy life. But when they migrated from the edges of the sea to the edges of the city, and were all massed together on street after street, all identical and with hardly any space in between, the sense of freedom became a sense of entrapment.

Where the bungalow is really popular now is in the United States. Somehow it came to stand for everything people there wanted: freedom, closeness to nature, efficiency, modern progress and, of course, low cost. My daughter Nora tells me there’s even a place in California called “Bungalow Heaven.”

Nora should know because her second husband builds bungalows—whole communities of them—in California. In fact, that’s how Nora met Bill: “Bungalow Bill,” I call him, like that song they play on the radio. He was building a house for Nora and her first husband Ted, and their two teenage girls. Then when Ted left Nora to go to India to meditate with the Maharishi like the Beatles, Nora was left with the girls, the bungalow and its builder. I went to their wedding last year, and stayed with them in their new house. It has one and a half storeys, overhanging eaves, and shrubs planted along the front. No servants’ quarters, but a big garage for their automobile. Lower ceilings than I was used to, and not much to look at inside. I couldn’t get over the kitchen, though, with all its cabinets and gadgets— including a machine for washing dishes! The family even eats right in the kitchen. The rest of the time they’re in what they call the “living room” watching television.

While I was staying with Nora and her family, I had quite a few conversations with Bill about his bungalows—and the girls joined in too, particularly Nora’s eldest, Melanie, who is reading Sociology at Berkeley and has her own ideas about how people ought to live.

Bill thinks he knows what a real bungalow is: “It’s an All-American house, originally from California.” When I protested that the bungalow originated in India he said that might well be, but it was “perfected” in California, and that’s the model that spread from West to East across the U.S., to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and even the U.K. back in the 1920s. “The bungalow embodied the Californian Dream, and it is the epitome of convenience and efficiency.”

This “Californian Dream,” he explained, had to do with a youthful, informal, outdoorsy lifestyle. The first “California bungalows” were summer houses. Their wilderness situation and their low silhouette contrasted with the uprightness of the Victorian villa, while the open interior of the bungalow did away with all the divisions of the Victorian house, and the stuffy social conventions that went with them, making for a “cosier” family life, or so Bill claimed: “Just look at the low roofline of a bungalow, how it radiates cosiness; think how it blends in with nature, instead of trying to dominate the countryside like some castle on top of a hill.”

How I bristled at that last swipe, directed at some imaginary Englishman (whose “home is his castle,” as the saying goes). But I had to forgive Bill all his not so subtle swipes at the British, for I could tell that he was actually reacting against his own Puritanical heritage. One visit to swinging London would cure him of the idea that the British remain locked in the Victorian era.

It was at this point in our conversation that Melanie intervened to point out that the rows upon rows of bungalows in the suburbs around Los Angeles do not blend in with nature, they obliterate it; that suburban sprawl has resulted in suburbanites having to spend more and more hours on the freeway commuting, which is anything but convenient, not to mention polluting; and, that people may once have found the California climate refreshing and wanted to be outdoors, but now they just sit in front of their air conditioners watching television, completely cut off from the natural world. “Air conditioners are not cool,” she said, as if she wished they didn’t have one. I don’t think we would have refused them back in the old days in India.

And, Melanie continued, the isolation from nature is matched by the social isolation of the nuclear family secluded within the “privacy” of its own home. Contrary to what all the women’s magazines say, home life for the housewife is not “relaxed, informal, and efficient”; rather, Melanie averred, it is filled with repetition, boredom and despair—an endless round of cooking, changing diapers, looking after “little ones” and trying to please one’s husband. You could tell Melanie would have none of this. That’s what comes of doing away with servants, I thought: my mother would never have deigned to do such work.

But the worst thing, according to Melanie, was the conformity, the way everyone aspired after the same possessions, the same “markers” of middle class social status. Americans had become far too “other directed” in the words of one of her profs, and the sameness was stultifying, as in the words of that 1962 song Pete Seeger sang, “Little Boxes.”

Little boxes on the hillside Little boxes made of ticky tacky Little boxes on the hillside Little boxes all the same

“But they’re not all the same!” Bill exploded. “I sit down with every one of my clients the same way I sat down with your mother.” Melanie rolled her eyes. Bill carried on: “We go over the plans, particularly those for the kitchen, and make adjustments, within limits, of course. Every bungalow I build is unique in some way, even if the walls and everything are prefabricated and the appliances all mass-produced. But that’s progress! And that’s the beauty of it: the bungalow almost builds itself it can be assembled so quickly—a matter of weeks —and, with all the labour-saving devices available nowadays, what more could a housewife want?”

I was swayed by Bill’s argument about the technological efficiency of the modern kitchen, until Melanie shot back: “How about a different division of labour? And, how about a life?” What Melanie had in mind was Dads shouldering some of the load, and Moms having their own jobs outside the home. She also pointed out that all the so-called labour-saving devices weren’t much good if they didn’t allow women to leave the house.

Bill sputtered on about how the bungalow encourages individuality because its style is so flexible, and how it supports democracy too, because everyone is on the same level! This provoked Cathy, Nora’s youngest, to bring up her plight as a teenager. Her room was only big enough to study and to sleep in. There was no space in the house for her to have her friends in (by which she meant no space where she was not under the watchful eye of her mother). There was no place in the endless winding streets of Downsview (the name of their subdivision) for young people to get together outside either. “But what about all the playgrounds?” her stepfather responded. Now it was Cathy’s turn to roll her eyes. (There seemed to be a lot of that going on in this household.) Obviously, Downsview had been planned for families with very young children and this had resulted in most young people feeling left out.

“The bungalow is clearly totally ‘dysfunctional,’ and so is Downsview,” Melanie opined. Bill gasped. Perhaps he didn’t know what “dysfunctional” meant. I don’t think I do either, but it certainly does sound bad.

“There is a solution, though,” Melanie proclaimed brightly. “This is America and we should do like our fellow Americans–Latin Americans, that is. Ever notice how from Mexico to the southernmost tip of Argentina, all the towns are laid out around a central plaza? The plaza is a place where everybody congregates, even teenagers. And the houses are laid out the same way. They are patio houses, which are like bungalows in that they are usually low, one-storey buildings, but the reverse of bungalows in the way they bring the outdoors indoors by having a patio at the centre, while distributing the rooms around the outer wall. The way the rooms all open onto the patio makes the house cosy, while the garden at the centre makes the house cool and, best of all, you are never cut off from the sky because there is no roof over the patio. You’re not cut off from other family either. The patio house easily accommodates extended families, since it is like a commune to begin with.”

I saw what Melanie was saying, but I couldn’t help feeling that had it not been for the disappearance of the veranda the bungalow could have remained a far more “functional” dwelling (to use Melanie’s language).

On another occasion I took this matter up with Bill. I said that I didn’t think the houses he built could really be called bungalows because, while they were simple, single-storey, single-family dwellings with extended eaves and open interiors, they lacked a veranda. He quoted me a line from some builder’s book he had on hand: “Although the bungalow has a number of distinguishing characteristics, none of them is so important as to be indispensable.” The veranda was one of these, he said, or rather, in the U.S.A. it had been replaced by the porch. Before World War II, I learned, most houses had a front porch and a broad stretch of front lawn. The porch was a place for entertaining and for talking to neighbours as they strolled by on a summer evening. After World War II, most people wanted their porch to be at the back of the house, overlooking a garden, and the front porch was replaced by a garage to house the indispensable automobile. The increased traffic and the decline of the evening stroll were further reasons for doing away with verandas or porches, though Bill had found that many of his clients still wanted to put in a bay window. That permitted them to watch without having to hear or smell their neighbours.

In any event, Bill said, the new buzzword among builders is “ranch house.” A ranch house is really the same as a bungalow, he confided. But people think ranch house sounds more distinguished, so I build them a bungalow and tell them it’s a ranch house.

One time when Bill (diehard salesman that he is) was going on about how perfect the bungalow is as a “starter home” for newlyweds eager to “move up” from an apartment in the city to a (cheap) house in the suburbs, where they can raise their children in “wholesome surroundings,” I pointed out that it made a good “finisher home” too. Seniors appreciate bungalows because there are no stairs and everything is in reach. It was the first time anything I said gave Bill pause. “Now why didn’t I think of that,” he said, and instantly began sketching a vision of a new subdivision called “Pleasant View” full of “specialty bungalows for old folks.” It had to be a new subdivision, he thought, because you don’t want to mix old people with young families, and it would probably have to be in some other state, like Florida, because of California’s youthful image, but what a great idea! Personally, I found the name sounded too much like a cemetery, and I think the generations should be integrated, not segregated, so I was not impressed.

Sitting here in “The Bungalow Hotel,” I have to wonder: Is the bungalow intrinsically flawed, the way Melanie seemed to think? That question begs the question of what a bungalow is, exactly. Colonial residence or single family dwelling? Vacation house or suburban house? Starter home or finisher home? If it is all these things and more, then perhaps it is the ultimate multipurpose dwelling, good for everyone, everywhere. And if that’s the case, it must be because it was a hybrid to begin with, a mixture of England and India.

I hear a lot of noise coming from the lounge downstairs. The Americans must have landed on the moon. They’ll soon be wanting bungalows there too, I suppose. Well, I’d better go and have a look. I like to move with the times.

This story originally appeared in our 2010 publication Journeys: How travelling fruit, ideas and buildings rearrange our environment.