Learning Naturally Results

Recollections by students of Rural Studio, Talca, Taliesin, and Black Mountain

Another tradition of architectural education exists outside urban centers and circumscribed pedagogies: unorthodox institutions which are themselves experiments in building community. We sought out alumni of four such schools to try to discover what sets them apart. These are their accounts.

Rural Studio

as told by Jennifer Bonner

During my time, from 2001 to 2003, there were seven staff and faculty members, twelve second-year students, twelve thesis students, and about six outreach students who came from all over the world. We also had prisoners helping students build their projects. It was a mixed social situation. Since there’s nothing really around—there’s no good coffee, there’s no television, and the internet connection sucks—our downtime would be spent around a bonfire, cooking or barbecuing and having discussions on a daily basis.

At the time, to be a thesis student at the Rural Studio, you would fill out a paper application that asked strange questions like, “Are you a Republican or a Democrat?” or “Do you prefer a hammer or a drill?” Before applying, my teammates and I contacted students from previous years and asked them if they had come across any needs, clients, or ideas for projects. Some students said we should talk to the probate judge in Marion, in Perry County, who had a vision for a former Works Progress Administration park that had been closed for almost a decade. He had put together a board consisting of the local mayor, a county commissioner, a biology professor, and people who were working at the state fisheries adjacent to the property. Rural Studio accepted our application, and the board became our client.

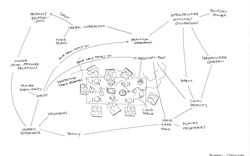

We started meeting with the board weekly, presenting them our design proposals, budgets, and how we would present the project to the public. They wanted a gazebo, and we knew gazebos to be kind of prefabricated objects from Home Depot, so as ambitious young students, we were thinking much larger. We thought we were going to build a series of five structures—a toilet, a bridge, a birding tower, a pavilion, and a fishing pier—but we realized that we had to strategically choose first the kind of civic space that would be necessary to open this park back to the public. We felt the pavilion was the right one. There were racial and social tensions happening around the Rural Studio. But I would say the reverse was happening with our project, in that everyone was working together towards the good of the project.

Once you’ve spent some time in a rural community, you try to find the most eccentric and interesting people. That’s how we met Mary Ward Brown, a short-story writer who lived her whole life in Perry County. We started spending time with her, learning about her writing and telling her about our project. Once, it came up that we were trying to figure out the materials to use on the pavilion, and she said, “Well, I have a cedar thicket down the road and I’d be happy to donate it to you. You’re going to have to cut it all down.” And so we went out with chainsaws and cut down dozens of trees and hauled them over to a guy in Greensboro, Alabama, who had a mill to cut down the logs into planks. The entire floor of the pavilion, which is about twelve hundred square feet, was made out of cedar from Mary Ward Brown’s thicket, located literally a mile away from the site.

After I completed my thesis project, I stayed for the following academic year as a faculty member. I had the title Clerk of the Works, which is someone who does a little bit of everything. I was teaching a course, reviewing students’ work, and picking up inmates from a local penitentiary in a Ford F-150. I would bring them to our campus to work with students and then drive them back. We had really interesting conversations, but the locals didn’t think it looked good and they called Rural Studio to complain. I’d also be driving around with a journalist from New York, or touring someone from the Oprah Winfrey Show around all the Rural Studio projects. Spending two years in the rural South presented a very different view of the world, which was emotional, unique, and overwhelming. Life-changing, really.

Talca

as told by José Luis Uribe

The rural condition is an integral part of training at the University of Talca, which is based in an intermediate city located between two capital cities: the regional capital, Concepción, and the national capital, Santiago de Chile. Until 1999 there was no school of architecture in this region, which is known as Valle Central. This was the same year I started. At the beginning, because it was a new faculty within a public university, the school had no specific building assigned to it. I remember some classes were held in an old carpentry workshop belonging to the faculty of forest engineering. It was really hard to listen to the professors with the sound of engines in the background. It was in that same room that we stayed up all night for the first time, trying to finish our project—actually, we stayed up studying for a maths exam, and we all failed!

We even had many classes in a forest on the university campus. We would bring our chairs to a clearing and hold the class there. Juan Román, the founder and at that time the director of the school, would wander around the forest, checking in on us—he was kind of a wolf with ninety Little Red Riding Hoods. He would then ask us about the spatial dimensions and the limits of our “classroom” in the woods. It was a very modest beginning and it was the strength of both teachers and students coming together that made the school take off.

The daily dynamics of the school were very active, because everyone was coming from somewhere else. Basically 80 percent of the students came from the countryside and some teachers came from different parts of Chile. There was always a constant coming and going—but always working—in the school, except during the “August Workshop,” when the school stops all its activities and becomes a transversal workshop. During this month, we use the valley as a large classroom, moving around the landscape and building interventions. Students from every year work together in small groups designing, managing, and building public spaces in rural areas.

One year, however, what we designed was not a building but an experience. With twenty students, we traveled across the valley, from the Andes Mountains to the Pacific coast. It was three days of pure celebration. The most important thing was getting to know the territory and getting to know each other as a group. It was in these intimate conversations, over a few glasses of wine, that different interests and ideas appeared. What you don’t see in the pictures of the built structures is actually that wandering around and sharing with students and locals.

For my final project, I designed a small oratory in the Andes Mountains, a place where people could gather to pray. The funny thing is that I found the place to build this project totally by chance. I was walking along the mountains, trying to find a building designed by Smiljan Radic. I couldn’t find it, but at the end I found the perfect spot for my project. I think that this project incorporated and reflected my experience of the school, as well as the materiality and rurality of the landscape.

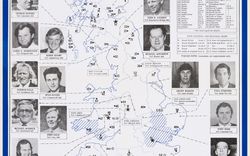

Taliesin

as told by Roger D’Astous

At Taliesin, on Monday morning, weekly assignments were on the pin board: construction of Taliesin buildings, maintenance, meal preparation, gardening or farm work at Midway, stone extraction from quarries as well as draughting ongoing projects. Why so many manual tasks were required was an inevitable question to a new apprentice. Seniors, sharing the same activities, knew the answer. Nobody had to report on it, but everyone realized that failing to contribute meant that this extra weight had to be borne by others! Of course manual chores were not the only daily activities; music, ceramic, sculpture, and cabinet making, with their respective shops and theaters, were available.

The draughting room, which we liked to call “the sanctum,” was the main target. With the supervision of Mr. Wright and seniors, we worked on actual projects (working drawings, details, specifications, etc.), a different approach from my previous standard schooling which was done mainly in classes. The master regularly made his round of tables. One day looking over a woodwork detail I was working on, he said: “Roger, this will not work.” Why? I asked. “Take it to the workshop and make it. You will see…” That is how I learned to make a good drawer detail that worked. It was later to be part of the Guggenheim project.

The draughting room had access to files and a library where all of Mr. Wright’s works were available, a tremendous source of information. It was up to us to “dig into it.” Even if the bell rang at 6:30 a.m., we very often spent a good part of the night studying them. Construction details of La Miniatura, sections of the Robie House, details of the Johnson Wax project, evolution of the Guggenheim Museum, project for Pittsburgh, Fallingwater, everything was there! All this from originals, bearing personal notes by the master, a real gold mine!

Another facet of apprenticeship was the construction of the buildings we lived in. Then did I understand why the “tool box” was mandatory when accepted as an apprentice, along with pencils and compasses. The purpose of this activity was to get in close contact with materials: to feel and understand their intrinsic nature. Using stone by making it as comfortable in a wall as it was in the quarry. Using wood correctly by revealing its grain and fiber. Using steel by demonstrating its unique tensile quality (cables in a suspended bridge). Using transparent glass to accentuate visual continuity between inside and outside or incorporate pigments to it combined with light.

Living inside a space created by Frank Lloyd Wright is a great experience by itself and this was provided profusely, at both Taliesin East and West. Living rooms, dining rooms, loggia and other spaces flowed into one another in a sublime way. As by phenomena of osmose, those interiors revealed themselves outside and become the exterior architecture, born from within, a direct result of the original plan concept.

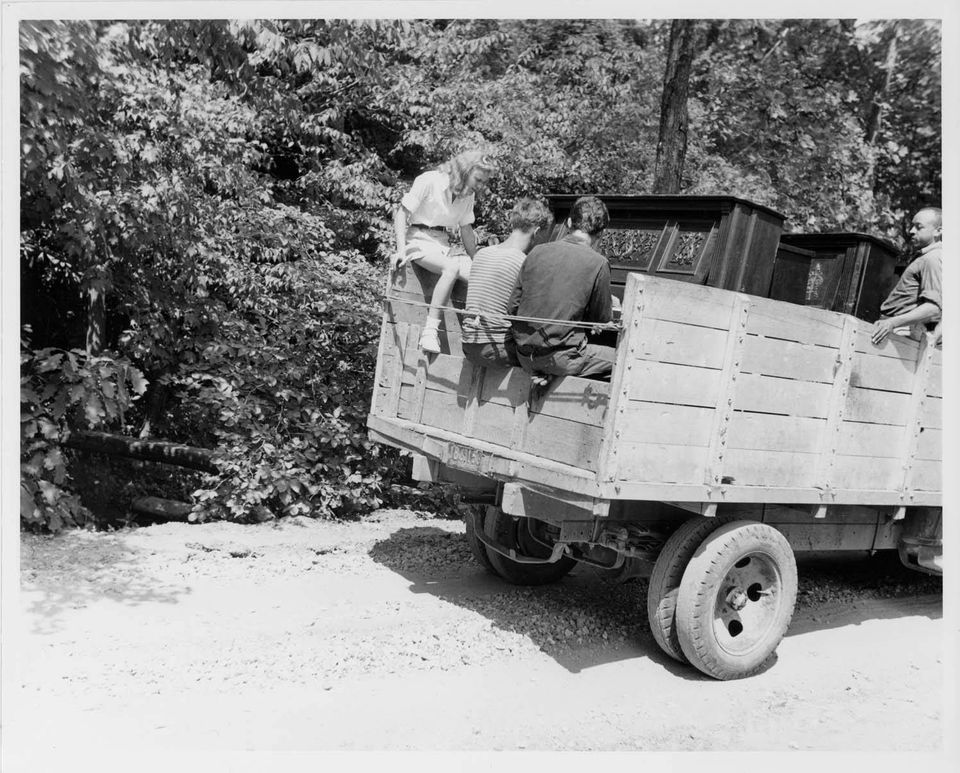

Black Mountain

as told by Herbert B. Oppenheimer

I was at Black Mountain from July 1942 until April 1943, when I was called into active service with the air force. I love that year. The Saturday-night dances; singing with Dr. Jalowetz in the chorus that contained as many teachers as students; classes with Albers and Bentley; and most of all the extraordinary people, the intensity of this small, brilliant community. I constantly talk about those days. They were mostly crowded with activity and pleasure. I recall then making some tortured figurines in clay, and Albers heard about this work. I showed them to him and was thrilled by his high praise. I realized then I could be a sculptor, and I have continued this art as an avocation related to my work as an architect. I remember a class with Albers in the basement of the new Studies Building. (We were still stuffing insulation into the space below the roof slab.) There must have been six or eight of us, a large class, and we were sitting about a large heavy table. He began talking about the weakness of the Gothic pointed arch, the lateral thrusts that had to be countered with the flying buttress and the pinnacle to prevent the arch from moving out to failure. And he was suddenly up on the table, his arms thrusting down to his hand on his tights, his legs moving apart—the buttress, the pinnacle, and the arch. The danger of physical collapse was frightening!

Frances de Graaf and Eric Bentley were the faculty members most concerned with the raging political world beyond the campus, and several of us would gather with them to talk and drink. Fran was a large graceful woman, who danced sedately but I recall one of our parties when she was inspired to place a chair on either side, crouch between them, and then to some stirring Russian dance music, with an elbow on each chair, she began a tsatska, furiously kicking out, bouncing up and down. Since that time and under similar conditions, I have repeated that stunt.

There were so few young men at school that each time Bob Wunsch or Fritz Cohen or Eric Bentley were staging an event, they conscripted me. I loved those Saturday-night performances: Ethan Frome, The Taming of the Shrew, and the singing.

My nine months at Black Mountain were probably the most intense several months of my life, and the happiest, but I have often wondered at the irony of my pleasure at a time when so much of the world was in a state of agony and horror, literally burning in pain. I am glad I had those nine months. Living in an isolated community of limited size and scale is perhaps even more valuable today, when we are in a world of vast scale and constant speed. We seem to be producing more and more, with ever-decreasing substance. Relationships between people now seem more limited, more fragile. But then I was eighteen years old when I was at BMC. It was an amazing time.

Jennifer Bonner and José Luis Uribe graciously recounted their college days to David Huber and Federico Ortiz in spring 2018. The account by Roger D’Astous, originally published in ARQ 60 (April 1991), was discovered in his archive at the CCA, which spans his entire career, beginning with his time at Taliesin between 1951 and 1953. Herbert B. Oppenheimer’s text first appeared as “Nine Months at BMC” in Black Mountain College: Sprouted Seeds: An Anthology of Personal Accounts, edited by Mervin Lane and published by The University of Tennessee Press (Copyright © 1990, reprinted by permission).