Found in Translation: Palladio – Jefferson

Photographs by Filippo Romano. Text by Guido Beltramini

A translation can often bring out the deep, innermost nature of a culture that cannot be transferred from one linguistic context to another. The theme of the images presented here is what remains in that two-way process: what has survived of American architecture despite Jefferson’s attempt to transform Palladio into a model for the architecture of a new nation, but also what has survived of Palladio in the American translation, confused by vague classicalism, British idioms, French modernity, and the quest for convenience. So what are the irreducible elements in his language that make it recognizable despite changes of context, function, clients, and climate?

Palladio made the great heritage of ancient Roman architecture available to architects for modern uses. He did so mainly through his treatise, the Quattro Libri dell’Architettura—the Four Books of Architecture. In Book One, Palladio illustrated the language of the five orders of architecture. In Books Three and Four, he published very careful drawings of the principal ancient monuments. Of course, at that time the ancient monuments were in ruins; they were fragmented remains. But Palladio published them reconstructed, and partly reinvented. We can use the metaphor of language to say that the ruins showed architectural Latin as a dead language, while the illustrations in the Four Books showed architectural Latin as very much alive, a language that could still be spoken.

But Palladio also constructed his own buildings.

Therefore, when we assess Palladio’s heritage in subsequent architecture—what we call Palladianism—it is easy to be excessively generic. There is a risk that Palladianism becomes everything vaguely inspired by ancient classical architecture. I remember having an argument a few years ago with an American colleague while we were working on an exhibition on Palladio in the USA; he described the Capitol in Washington as Palladian. I tried to point out to him that the dome had been inspired by Bramante’s dome at Saint Peter’s, as published by Sebastiano Serlio in 1540. But I couldn’t make him change his mind!

So I would like to reflect with you on some specific elements of Palladianism, cases in which architects have truly captured the spirit of Palladio’s way of designing and building.

Read more

One good example comes from the villas and the way that Palladio fuses together the landowner’s house, the barchesse (the outbuildings) and all the buildings generally involved in farm production, such as those containing the stables, stalls, cellars, farm equipment, and the rooms where the silkworms were raised.

We must bear in mind that the Palladian villa was not simply a summer retreat but a place of production, organized for the purpose of work in the fields. Of course, even before Palladio, there had been farms consisting of the landowner’s house, the barchesse, dovecots, and the yard for threshing wheat. All these elements are found in the Villa Emo. But the difference is that in the Villa Emo, Palladio gives an overall form and unity to these functional buildings; he aligns them and so effectively invents a new type of rural building—the villa.

The interesting thing is that this invention of a new type of building stems from a mistake on Palladio’s part. He saw and measured the ruins of the Temple of Hercules Victor at Tivoli, but he was convinced that they were the ruins of a great imperial villa. He mistook the temple cell for the block of the landowner’s house, and the temple porticos for the barchesse. In reality, the ancient Roman villa had nothing of this “Palladian form” but rather was a shapeless group of buildings encircling some courtyards. Nonetheless, on the basis of this inspired error, Palladio changed the way of living in the country.

Therefore when we say that Jefferson’s villa-mansion at Monticello is “Palladian,” we don’t mean it is Palladian because of the forms of the house, but because of the relationship between the principal building and the buildings used for work purposes. They are integrated into the house. Similarly, there is a Palladian relationship in the University of Virginia between the large block of the library and the pavilions arranged around it, which house faculty residences and classrooms. It is this fusing together, this integration of the main building and the two wings of the other buildings that is Palladian, not the “rotunda” form, which is actually inspired by an ancient Roman building—the Pantheon.

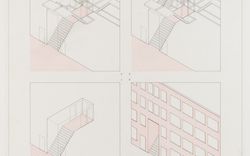

When we consider, for example, the plans of so-called Palladian buildings in the eighteenth century, we find that they are very different from Palladio’s originals. Palladio’s buildings are characterized by the harmonious proportional relations between three kinds of rooms, which are square or rectangular in form. This suite of rooms is Palladio’s invention. The rooms, however, are arranged one after the other, and to reach the last you have to go through the others. There is no privacy. There are no access corridors, which was something that became indispensable in the eighteenth century. This reflects a big difference between the way people lived in interior spaces in the sixteenth century and in the eighteenth century. In the sixteenth-century Palladian residence, whether a villa or a palace, there were no bedrooms or dining rooms. There were no rooms dedicated to a specific use. People ate, slept, and received guests in the same room. This was a kind of nomad way of living in a house; you moved from one room to another according to the season, in response to the cold or the heat. Four-poster beds with curtains were used to create some privacy in the rooms and to protect from the cold. But then in the eighteenth century, everything changed. The plans of houses included corridors, antechambers, and specific rooms for dining, studying, and receiving guests. The interior of Monticello illustrates this very well. Moreover, Jefferson added a number of inventions to make life more comfortable. For example, the bed was arranged so that it divided the bedroom and the study. So you could get up from one side of the bed and be in the study, or you could get up from the other side and be in the bedroom. In short, there is nothing Palladian at all about this plan!

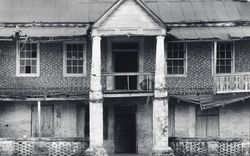

Aside from the integration of the main building with the barchesse, another marker or significant feature of Palladianness is the pediment on columns set on a villa facade. This is an ancient feature. We find it on the models of ancient Roman villas, where we can see a pediment above a loggia. The idea of putting a temple pediment on a villa was not Palladio’s invention, however. It first appeared on a villa created by Lorenzo the Magnificent and Giuliano da Sangallo in the mid-fifteenth century at Poggio a Caiano, near Florence. But it was Palladio who made it a distinctive sign on all his villas. And this element was then borrowed by subsequent Palladianism. The pediment with columns was transferred from the sacred context of the temple to the domestic sphere of the house. It has characterized models of the villa from the second century AD up to the unwitting Palladianism of freed American slaves’ houses in Liberia in the nineteenth century.

The materials of American Palladianism—wood and brick—are interesting. They are much closer to the Palladian originals than we would imagine. In fact, Palladio often used wood clad in marble plaster and bricks instead of more costly stone. He used wood for the lintels, both to economize and also to have wider intercolumniations. But in the nineteenth century this “low-cost Palladio” was transformed into a more monumental Palladio, when the wood parts were replaced by stone parts during restorations. Fortunately, in several buildings that were not restored in the nineteenth century, we can still see the original elements.

From the social point of view, Palladio’s villas created a new type of country residence, developing farmhouses into mansions fit for gentlemen. The social aspects of this design approach were peculiar to the Venetian Republic, in which there were no kings, courts, or courtiers. The Venetian nobles spent part of the year in the country and managed their own farm business while devoting time to architectural quality, reading the classics, and the pursuit of physical well-being.

When the ruling classes in the United States began to forge their own architecture, they looked to Palladio. This was not only a question of taste. It was also connected to the way architecture in Venice reflected that city’s identity as a republic. For centuries, the Venetian Republic had been identified with the Republic of Plato and had three levels of government: monarchy, with the figure of the doge (an elected king with no dynasty); oligarchy, with the Council of Ten; and democracy, in the form of the Senate.

The theme of the villa—be it Venetian or American—involves the representation of power in architecture. In the American case, it also points to the dark side of the American conscience: in Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained, liberation comes with the destruction of Candyland, the slave owner’s Palladian manor.

Thomas Jefferson famously claimed “Palladio is the Bible!” but he had never visited the Veneto and only knew Palladio’s work through the Quattro Libri, or rather The Architecture of A. Palladio, an unfaithful translation of the Four Books published in London by Giacomo Leoni between 1715 and 1720, with the images transfigured by baroque taste.

Convinced he was working from the original text, in his project for the President’s House in the form of the Villa Rotonda, Jefferson designed a dome with light filtering through glazed windows. The inspiration for these were actually the large oval windows in the dome of the Villa Rotonda as presented in the English translation and completely invented by Leoni. They were enlarged, however, into long glass segments, modelled on the dome of the Halles aux Blés, which Jefferson had admired first hand in Paris in 1786.

The resulting design is typical of Jefferson’s Palladianism: a combination of enthusiasm and misunderstanding, as well as ingenuity and pragmatism.

Found in Translation: Palladio – Jefferson is a project by Guido Beltramini, Director of the Centro Palladio, and photographer Filippo Romano that resulted in an exhibition we carried out in 2014 and 2015.