From a height of one metre

Émilie Retailleau reflects on the CCA’s youth programs

Due to the dominant position of adults over children, our cities and built environments are not designed for young people. However, children are experts of their own spaces, and their perspectives and voices are essential to shaping and building lived environments because they use and inhabit them just as much as adults do.

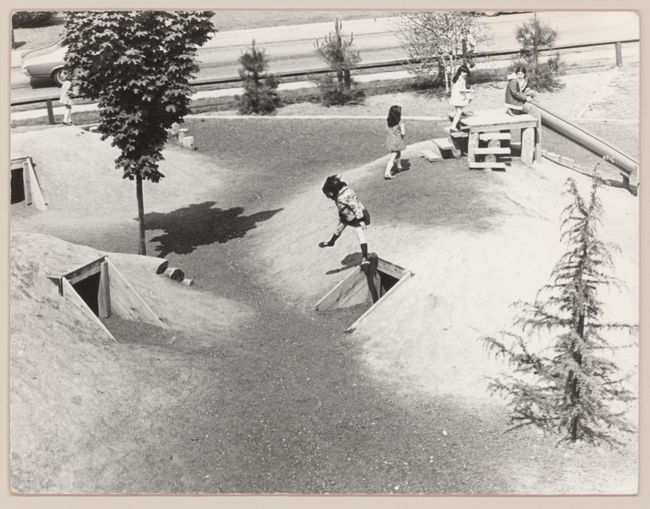

How do we see space from a one-metre height? To think from a child’s height, we must radically shift our perspective. Some architects and landscape architects—like Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, who designed many playgrounds—pay close attention to the multiple uses and temporalities of space, borne by the bodies and minds of children.

View of children playing in Talmud Torah School Playground designed by Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, Vancouver, 1970. Cornelia Hahn Oberlander fonds, CCA, ARCH401976. Gift of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander

So how can the CCA’s public programs also create the conditions for this shift in perspective? Welcoming young people to the CCA means talking with them and sharing our spaces, making room for their opinions and interests, but not only that. We do not necessarily want to train a future generation of architects. Rather, we seek to create transformative situations for ourselves and for young people with the aim of supporting their open reflection and participation in and for their built environment.

We deliberately avoid words such as “mediation” or “education” in our programming. Instead, we explore architecture through the more indirect paths of questioning, conversation, research, and experimentation. Our youth programs do not produce didactic tools or popularize knowledge for young people. We address complex contemporary issues with youth of all ages: the impact of buildings on natural and urban resources (To Live Differently), as well as on landscapes and territories (What Makes a Landscape?); the collective and intimate uses of space (Architecture Challenge); the social, economic, and political dimensions of architecture (Youth Collective programs The Urban Unknown and Grown from the Concrete); the physical, sensory, and emotional perceptions of the spaces we pass through and inhabit (Disco Tomorrow?). We explore the different ways in which our built environment reflects—or fails to reflect—our society, and how it creates, exacerbates, or alleviates friction among communities. Through our conversations with young people, we have learned that they sorely lack meeting spaces outside of school, and that social connections are an increasingly important issue for them. They also have a heightened awareness of the environmental and socioeconomic challenges facing our society, in which they want to play an active role and where their actions must be meaningful.

Although ephemeral and experiential in nature, our youth programmes aim to highlight, articulate, and question young people’s opinions on the built environment. They forge a space where dialogue can flow without promises, evaluation, expectation and where ideas and concepts can be freely approached, explored and explored in depth. Because we do not know how these reflections will take shape or whether they will transform or be taken up and developed further by young people, this is one of the most modest forms of transmission and learning.

We have no dedicated mediation space or permanent workshop room. The CCA’s youth programmes and activities take place everywhere: in the galleries and museum spaces, nearby parks, and community centres. They open a discreet counterspace away from defined frameworks. In these spaces, we try to create moments of direct exchange, questioning, research, and experimentation. These moments are constantly renewed and take on varying forms and levels of intensity. We avoid readymade formulas to our programs. The foundation of the CCA as a research institution keeps us from doing so.

We are surrounded by a diverse group of committed adults who are open to learning: architecture and museum experts, graphic designers, cultural and social workers, artists, entrepreneurs, teachers, educators, citizens, activists, parents, school services, community organizations, and the CCA staff. We work with adults who help to create points of contact between young people and the museum, and between their own ideas about the built environment and those held by young people.

However, this mission remains fragile and vulnerable. Numerous obstacles, both material and institutional, limit processes of including young people’s thinking in museum spaces and other environments. What’s more, young people also suffer from social inequalities and ethnic and gender discrimination.

Faced with the erasure of children from the built environment, creating public programs to talk about architecture, for and with young people, is not a heroic gesture. It is often a modest social and political gesture toward intellectual involvement, and the fragility of this mission makes it urgent to create tenable and necessary counterspaces to involve young people.

This text is a preamble to a series of upcoming articles giving adults, children, and teenagers a turn to speak about their relationship with built spaces and present their ideas on current issues in architecture and urban space issues—and their role in defining them.