Can Things Be Devious By Design?

Excerpts from a conversation between Francesco Garutti, Stephen Graham, and Albena Yaneva

Following a preview screening of Misleading Innocence held at the CCA in 2014, Francesco Garutti discusses the story of the Long Island overpasses and the politics of architectural détours, with Stephen Graham and Albena Yaneva.

- FG

- The subject of Misleading Innocence is an academic debate and a fragment of the theoretical research that, thirty years ago, changed our way of observing the pieces of cities and the technical objects we live with. Maybe it is simply a circumstantial research project that intentionally occupies the ambiguous space between the history of American material culture and the rumours of an urban legend. The film was conceived as a curatorial tool to provoke a debate, to collect different point of views and possible readings of the facts and of the story.

- AY

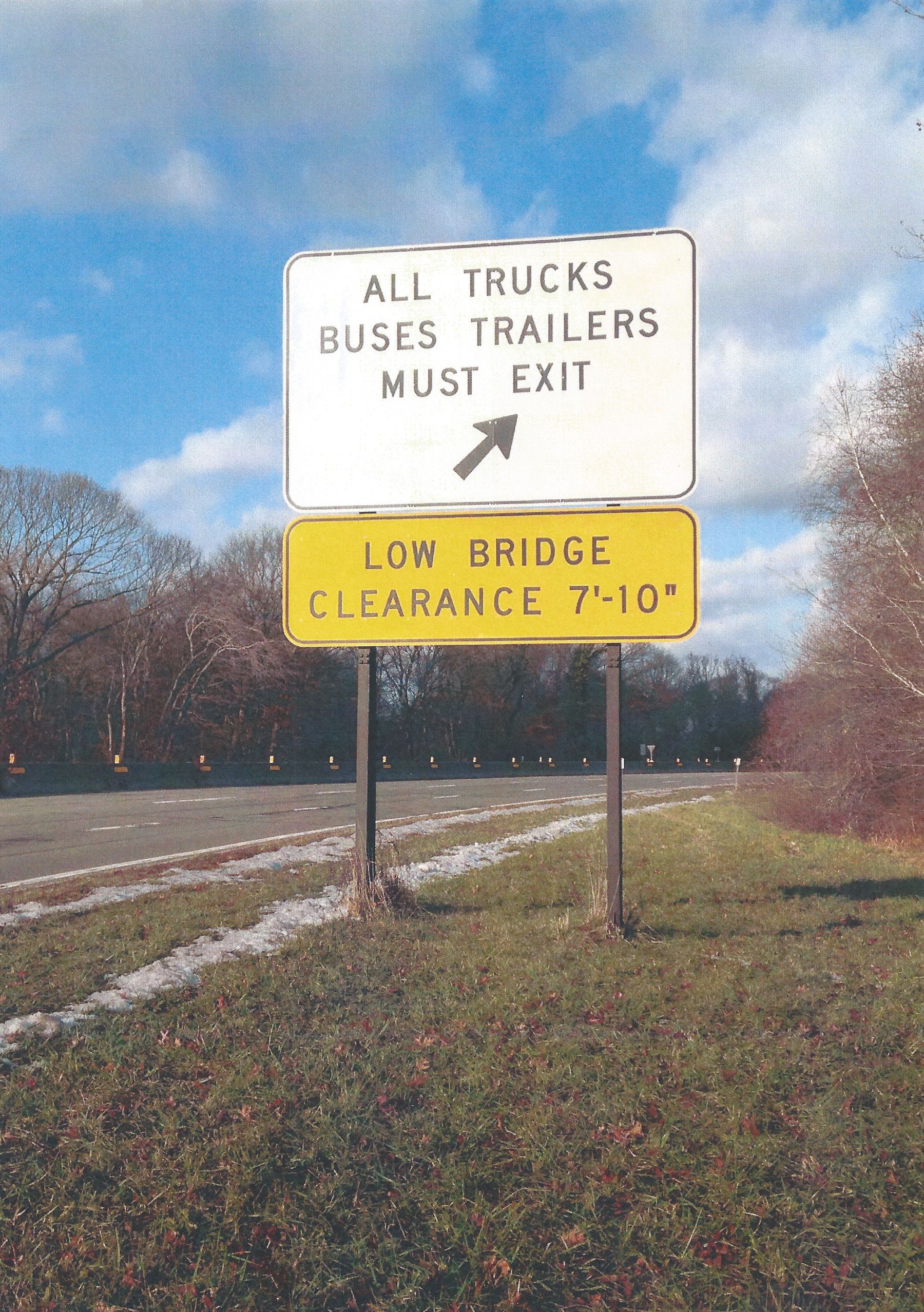

- It’s interesting that you don’t explicitly critique Winner’s1 idea about Moses designing deliberately low bridges to stop bus traffic, but that you rather involve him as just one of the protagonists in this debate. Winner’s interpretation presents a very anemic version of technology, as only the height of the bridge is discussed. There is a funny moment in the film when we see Winner picking up the tape measure as a way of demonstrating the bridge’s height. Yet, there is no mention of materiality, shape, construction, technological innovations, users, and so on; nor is there mention of natural forces and how they happen to be channelled in a specifically shaped artefact—the “low bridge.” On the other side, only one type of politics is discussed: racial discrimination. Winner reduces the politics of Moses’s design by putting the bridge’s height and racism into a kind of equation of causal explanation that reproduces the divide between the political and the technical. In the film, the bridge is neither simply material, nor is it merely political. We see its materiality with the series of close-ups. We witness its different dimensions. We see the technology doing things. We see this artefact being used, failing and being repaired. So, we witness the agency of a very complex artefact, which you bring out visually by illustrating its various dimensions and the many different actors that gather around it and maintain it on a daily basis. We watch this wonderful failure of the artefact to perform what it’s meant to perform, and so we have a much more complex understanding of both technology and politics.

Francesco, you present a much more hybrid artefact because you’re interested in what it does, not just in what it is or what it means. The message here is that if we follow the process of design or the processes of contestation, of daily use or maintenance, we will gain unique access to architecture and urban infrastructure.

-

Langdon Winner reported that Robert Moses urposefully designed low overpasses to limit access to Long Island’s leisure spaces in “Do Artifacts Have Politics?,” Daedalus 109, no. 1 (Winter 1980): 124; citing Robert Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Knopf, 1974), 952. ↩

- SG

- I think this film is a really powerful evocation of some of the complex debates about cities and infrastructure that have been very influential, but only within a fairly narrow sphere of the social sciences. It’s great to see this enter the visual domain, because there are very few good documentaries about infrastructure that go beyond clichés and give a nuanced interpretation of the politics of technological artefacts within an infrastructural landscape. It’s important to make the point, first of all, that these are political objects. Going back to Moses’s time, we have to locate these objects within the broader modernist discourses that held that a certain individual could heroically remake an entire urban landscape based on some ideas of progress, modernity and the future. The film integrates these points elegantly through the protagonists, including scholars in the field of social studies of technology we have read for years and the bridge itself, and shows us the countless ways in which it’s being incorporated as an agent into political, cultural and social discourses.

There’s a lot of evidence of the careful planning and design of highways by political elites to push through massive engineering projects with a view to the deliberate destruction of particular neighbourhoods. According to Marshall Berman,1 this was done to empower the car-owning minority who would move daily up and down these landscapes. There are many other urban justice issues that surround questions of highways, but we could go on for hours discussing these.

Read more

- FG

- I understand what you mean. That’s why from the beginning of the research and filming I asked myself how much to include of a story that contains many layers and subtopics: from the urban history of twentieth-century New York, to studies of the unexpected effects of designing artefacts and technologies. It was fascinating for me to discover how the debate I was re-enacting was at the core of Science and Technology Studies, a relatively new field.

- AY

- The documentary is inspired by the tradition of STS founded in the 1970s with the work of Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar.2 They followed “science in action” rather than “ready science” and tracked the everyday rhythm of a lab. They used ethnographic observation to follow science in the making so as to understand the production of scientific facts, scientific visualization and the material operations that accompany scientific work.3 As Steve said, we grew up intellectually with this debate about social constructivism versus actor-network theory, control versus contingency. With the film you capture this very specific moment of intense scholarly controversies in the STS field in the 1990s, and you take it as a way to address issues of technology and politics in the field of architectural studies.

-

Marshall Berman, All that is solid melts into air: The experience of modernity (New York: Verso, 1983). ↩

-

Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar, Laboratory life the construction of scientific facts (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1979). ↩

-

The works of Michael Lynch, Karin Knorr-Cetina, Bernward Joerges, Michel Callon, Madeleine Akrich, and Peter Galison, among others, have led to important developments in the thinking about the practices of science, technology, and innovation in the 1990s. ↩

- FG

- There are two issues that I’d like to bring up with you. Controversy—in the end the film is itself a contention and it looks at the bridges as contested artefacts—and the topic of breakdown or failure.

- SG

- The issue of the accident is related to infrastructure, which is a socially defined term. There are lots of technologies that are not rendered as infrastructure. The anthropology of infrastructure suggests that in order to become infrastructure, a technology has to become invisible, or at least culturally invisible—obviously certain infrastructures are quite literally pushed underground, beneath the city, or sent through the airwaves of space. The normal function of infrastructure in many advanced economies—it’s different in the Global South where this stuff isn’t a matter of course—is a smooth, uninterrupted flow that’s taken for granted. This is what sociologists call the black box. As Bernward Joerges says, technologies are black-boxed when they become culturally invisible. Accidents are moments when these arrangements become much more visible, ironically and paradoxically, because the infrastructure’s not working. The 1998 ice storm in Ontario and here in Montreal is one example.1 Arcade Fire, the local band, did a song about what it’s like to live in a modern industrial city without power for a long time. You’re in the dark, you’re in the cold, you can’t get money out of the ATM… The infrastructure becomes profoundly visible by not working. The eruption of the volcano in Iceland is another example. All of a sudden the entire global airline system was in disarray. You could pick up a newspaper and see cross-sections of five different types of jet engines on the front page. The minute the aircraft started flying again, these diagrams vanished. It was the same with the disaster at Fukushima. It’s possible to contest the politics of technology much more powerfully during those moments of accident. It’s much harder when the stuff recedes back into the infrastructural substrate, which people tend just to take for granted.

- FG

- I think Latour’s list of situations in which it’s possible to detect the hidden complexity of infrastructure is relevant here. He talks about failures, breakdowns, strikes, innovations, and archaeology.

- SG

- I agree. And how does political action exert the most power in cities today? Is it by coalescing in city streets, as was done in traditional times of revolution? Maybe not. If you want coercive power over the entire economy, you close down the airport! There’s a good example from a few years ago: a strike of the people who bring the food to Heathrow Airport. It’s a huge labour process; workers are often very badly paid and work in very poor conditions. And it’s totally invisible. I don’t think many of us ask, “Who produces this really horrible meal that I’m getting every time I fly?” The strike made this world visible: a huge company called Gate Gourmet, undocumented migrants from all over the world, and terrible labour conditions. You can see this is a very powerful sense of political vulnerability because we live in infrastructural societies, in cities that are utterly reliant on whole suites of infrastructures. We don’t have alternatives to these systems, and that makes them vulnerable.

- FG

- A strike empties the building and brings the people out into the streets, which reveals the building as a body of bodies. Albena, I’d love to go back to the idea of the controversy that is so central to your research at the intersection of STS and architecture studies.

- AY

- Design controversy denotes shared uncertainty over the nature of design or contested urban knowledge; it refers to the series of uncertainties that an urban project undergoes and is a synonym of “architecture in the making.” These issues are close to the public because of their complexity. Mapping controversies covers the research that enables us to describe the successive stages in the production of architectural knowledge. The film is a strong example of the controversy-mapping approach, as you map the scholarly debate in the 1990s. In a way you are thinking like an actor-network theorist. You do not question the essence of the artefact; you don’t ask whether this artefact reflects politics or not, as Winner does. Rather, you bridge the divide between politics and architecture. To do this you follow as many different actors as possible, you listen carefully to what these actors have to say, not just to the interpretations and the stories; you also trace the actors’ positions and the variety of elements and issues that the bridge is made of, together with the vast range of factors that impinge on design, use and maintenance. This helps us understand the architectural character of objects and the urban character of networks and artefacts, instead of trying to provide an explanation of architecture. The film takes us into the world of the controversy around social constructivism as well as into the bridge’s world.

- FG

- Reading Winner’s essay, I was immediately fascinated by the idea of masking intention and by the degree to which it’s possible for a designer or an architect to create ambiguous artefacts or simply artefacts with double functions. It’s of course this specific aspect of the Winner text that suggests the topic of deviousness. Could you mention some examples of artefacts that embody and define politics in relation to design and STS?

- SG

- There are lots of examples. The field of STS relies on thick descriptions of certain cases: doors and keys, and bicycles as well. There’s even a narrative of the history and design of the Portuguese galleon, which facilitated the entry of Portugal into imperial navigation. Bakelite telephones are another example. You name it—you can find a set of very detailed ethno-methodological discussions. Then there’s the whole debate about the cyborg, the biotechnological debate that Donna Haraway has been very influential in forming. She renders gender-political discussions of the fusing of technology and bodies, which is hugely important. It’s difficult to find an example that’s been discussed as extensively as these bridges have been, though.

- AY

- There are many other interesting examples. The typology of parliament architecture is one. Jean-Philippe Heurtin for instance studies the shapes of the parliaments in France at the time of the Revolution. He argues that the shape of parliament chambers has an impact on the way deliberations happen and on overall parliamentary culture. He states in particular that the successful process of “political” deliberations in the first parliaments at the time of the French Revolution was cognitively conditioned by the spatial arrangement of the semi-circular assembly chambers. We can in a similar way say that the shape of this theatre and our seating arrangement have an impact on the way we talk right now. What Latour says in the context of the tradition of mediation is useful here. We cannot say that this chair, the chair I sit on, makes me sit in a particular way and determines my behaviour. But chairs, artifacts, technologies, material arrangements and architectures do allow a certain number of activities to happen; they enhance ways of acting, help performance, mediate and facilitate actions.

- FG

- That’s the definition of political, right?

- AY

- Exactly. That’s a soft way to talk about what technology does without folding in architectural or social determinism.

-

See also Stephen Graham, ed., Disrupted cities: When infrastructure fails (New York: Routledge, 2010). ↩

- SG

- As Latour says in the film, certain micro-elements of the built environment can be easily interpreted as political. The benches that make it impossible for someone to lie down are a classic example of what geographers call revanchist politics, which is all about gentrifying urban spaces with the elite user in mind, and excluding marginalized communities. It’s not simple cause-and-effect technological or environmental determinism, but the intentionality is pretty obvious.

- FG

- Bruno Latour’s use of the term devious interests me. He refers to deviousness as a non-direct effect, something that is conceived of as indirect but that, in this case, has moral implications. And moral implications are almost impossible to detect and verify. Devious is connected to the idea of détour. For STS scholars, détour is the crucial topic to be explored in order to study techniques and their ecosystems and effects, rather than the moral implications related to the devious. What do you think?

- AY

- Detours are important indeed. You never follow a linear path of actions in design, in use, in dwelling or in maintenance. This is very relevant for architecture: a building never looks exactly like the initial drawings or plans. The idea of détour is very different from Steve Woolgar’s interpretation. Woolgar is concerned only with the discourse, which implies that the bridge never changes, only its interpretation does. The film presents a rather different story: the bridge is a changing object here, and is different in every single shot. It’s changing all the time, and not just discursively, but also materially and relationally.

- SG

- Well, many things have to be materially remade, otherwise they collapse. There’s a huge crisis at the moment—particularly in North America—because infrastructure is not being remade. There’s an absence of investment in maintenance. There are some very clear examples in which there is real evidence of intentionality including, as we’ve discussed, the spiky landscapes which are specifically designed to be anti-homeless. But even in that case, there is a set of practices and politics that makes the interpretation more complex. Architects and designers often don’t control the actual shape of the project in the end. They certainly don’t control maintenance. How many tower blocks in cities around the world have failing elevators? Any notion of a modernist lifestyle collapses the minute that the elevator doesn’t work. And architects don’t control the way that the space is used, either. There’s often a lot more flexibility to the use of spaces than is intended.

- AY

- If we follow designers at work, we see that the final result can be completely different from the original plan. There is one particular intention—usually a good one—but then so many factors impinge on the process of design, and so many detours appear that the project takes on new dimensions. A recent example is Frank Gehry’s Stata Center on the MIT campus. He had the good intention to design a wonderful building for scientists, but he never consulted them. So at the end of the process, these scientists were unhappy with the space. They said, “This is a beautiful curved space, but we feel like rats in here.” The architect’s intention was good. But from the point of view of the users, this design could be interpreted as “devious” in Francesco’s terms because it results in a negative experience of space.

This conversation was published in our digital publication Can Design Be Devious? (2015).