Querido Amancio, organized on the occasion of our new Amancio Williams fonds, featured a public reading of personal letters during which participants—Emilio Ambasz, Florencia Álvarez, Giovanna Borasi, Fernando Diez, Kenneth Frampton, Mario Gandelsonas, Juan Herreros, Martin Huberman, Cayetana Mercé, Inés Moisset, Ciro Najle, Ana Rascovsky, Claudio Vekstein, and Claudio Williams—commented on the legacy of Amancio Williams.

Querido papá

Claudio Williams imparts a legacy

Dear Dad,

After many years of maintaining your archive and placing great effort and personal investments into disseminating your work, we, your children have finally decided to donate the archive in its entirety to the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montréal, Canada.

This is the culmination of a long process that began with your death in October 1989, though it truly began much earlier, when you started to develop your first works in 1943.

As you know, the archive comprises some 7,000 plans, over 5,000 letters, over 7,500 negatives and slides, a large number of printed photographs, all the publications about your work published during your lifetime and since your death, six models, and a large collection of plates, all full-size and high quality. To document and present your projects, you had produced these plates of great expressive force, typically in series related to each of your projects, and they are, in themselves, powerful aesthetic displays.

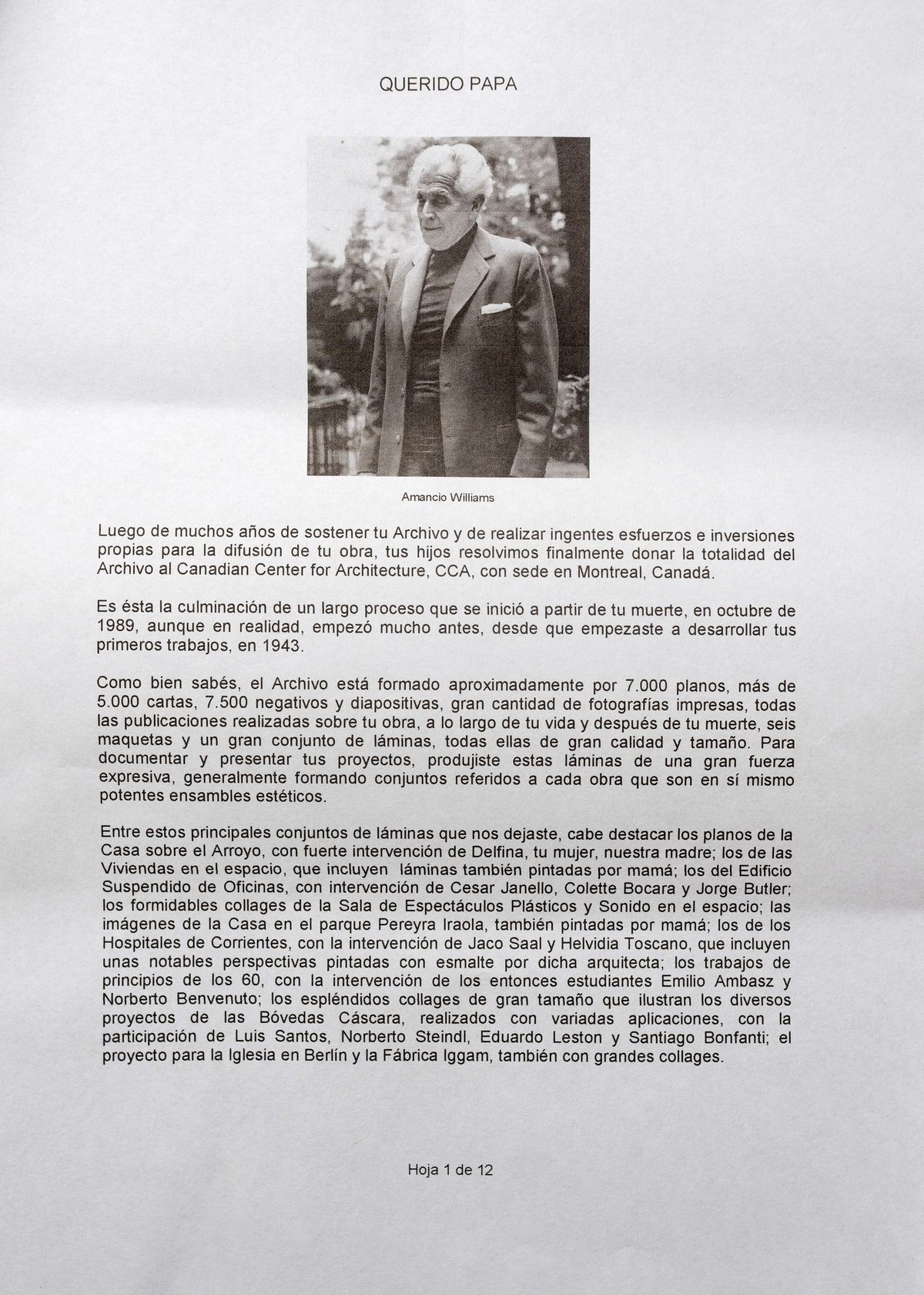

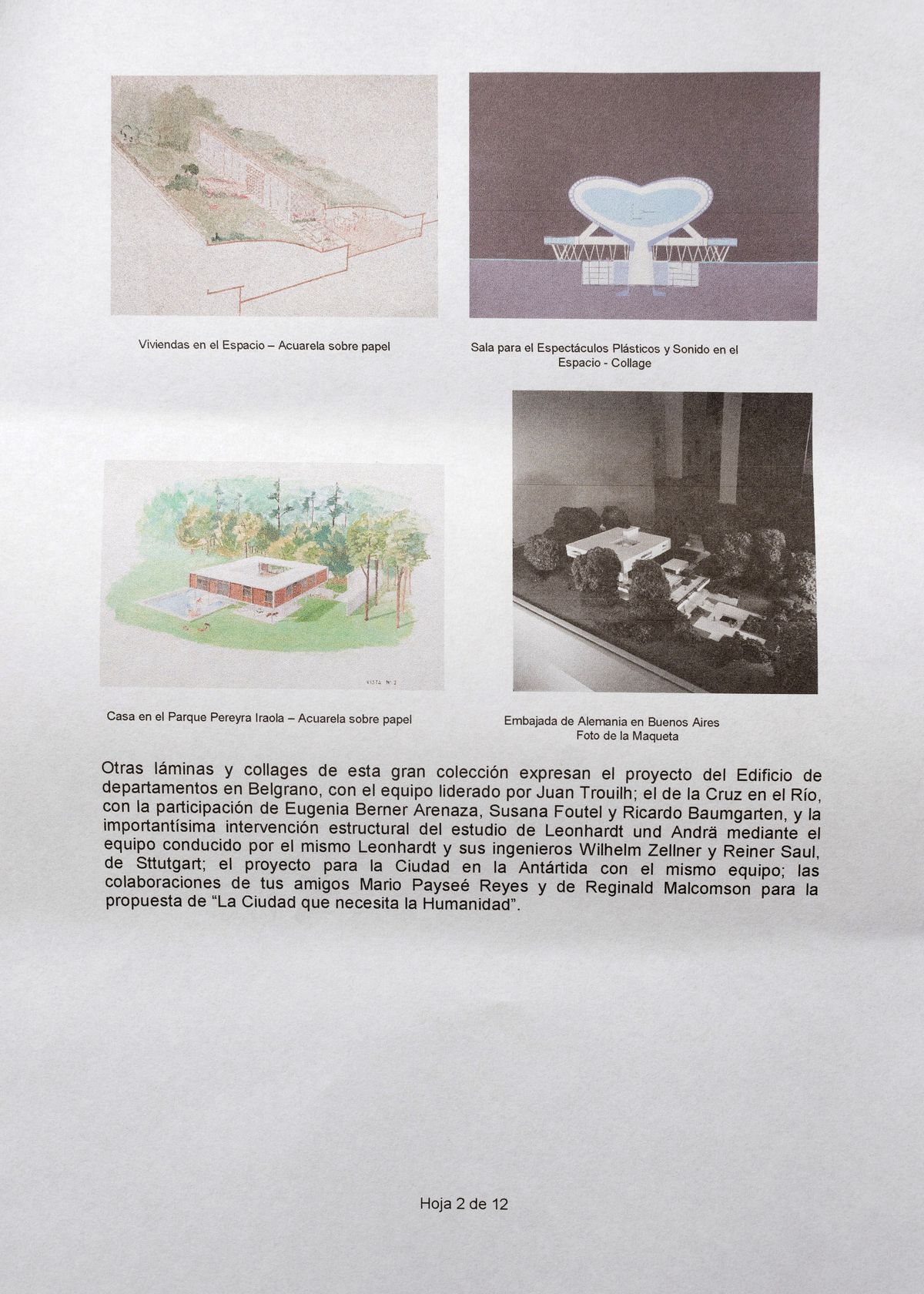

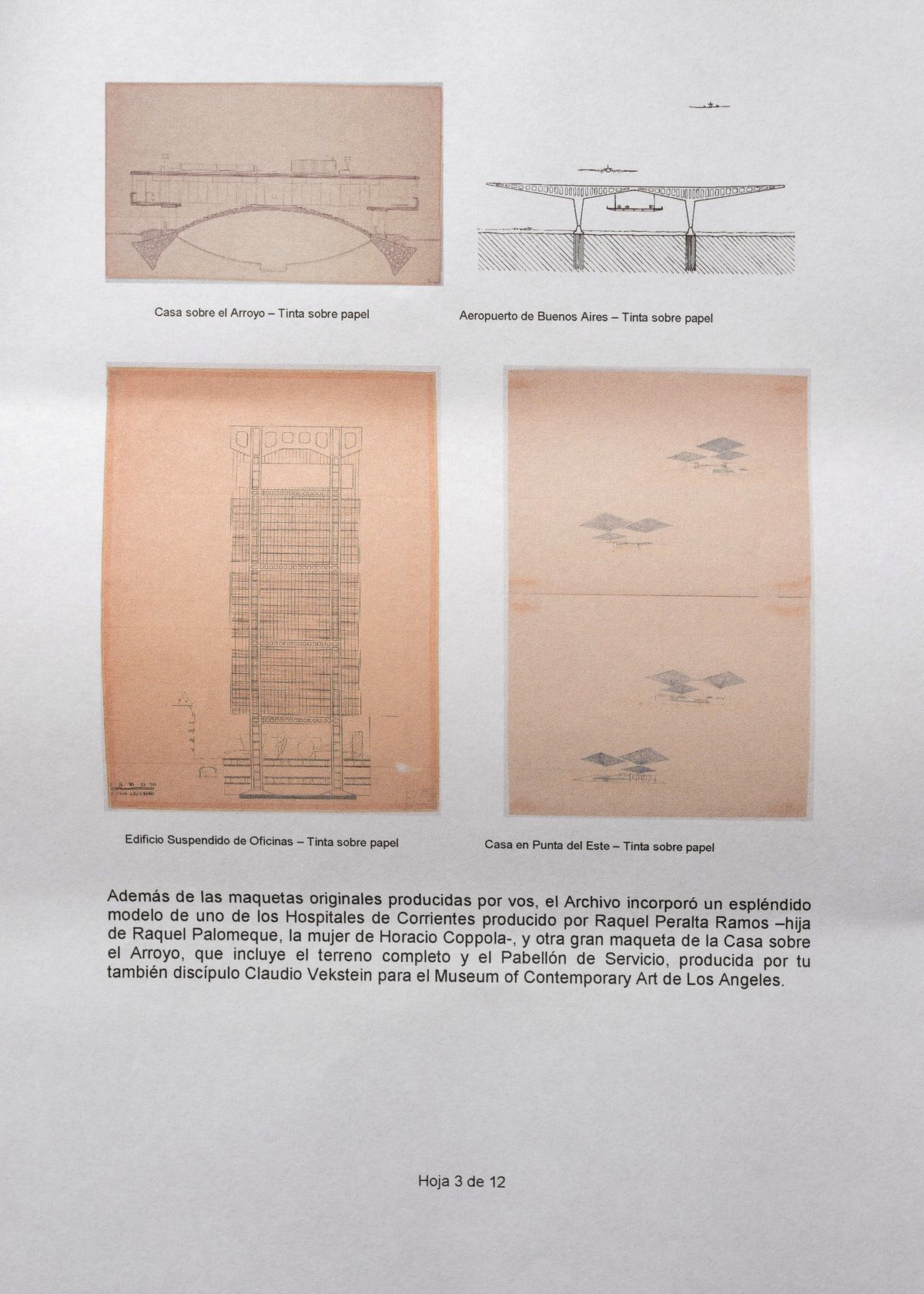

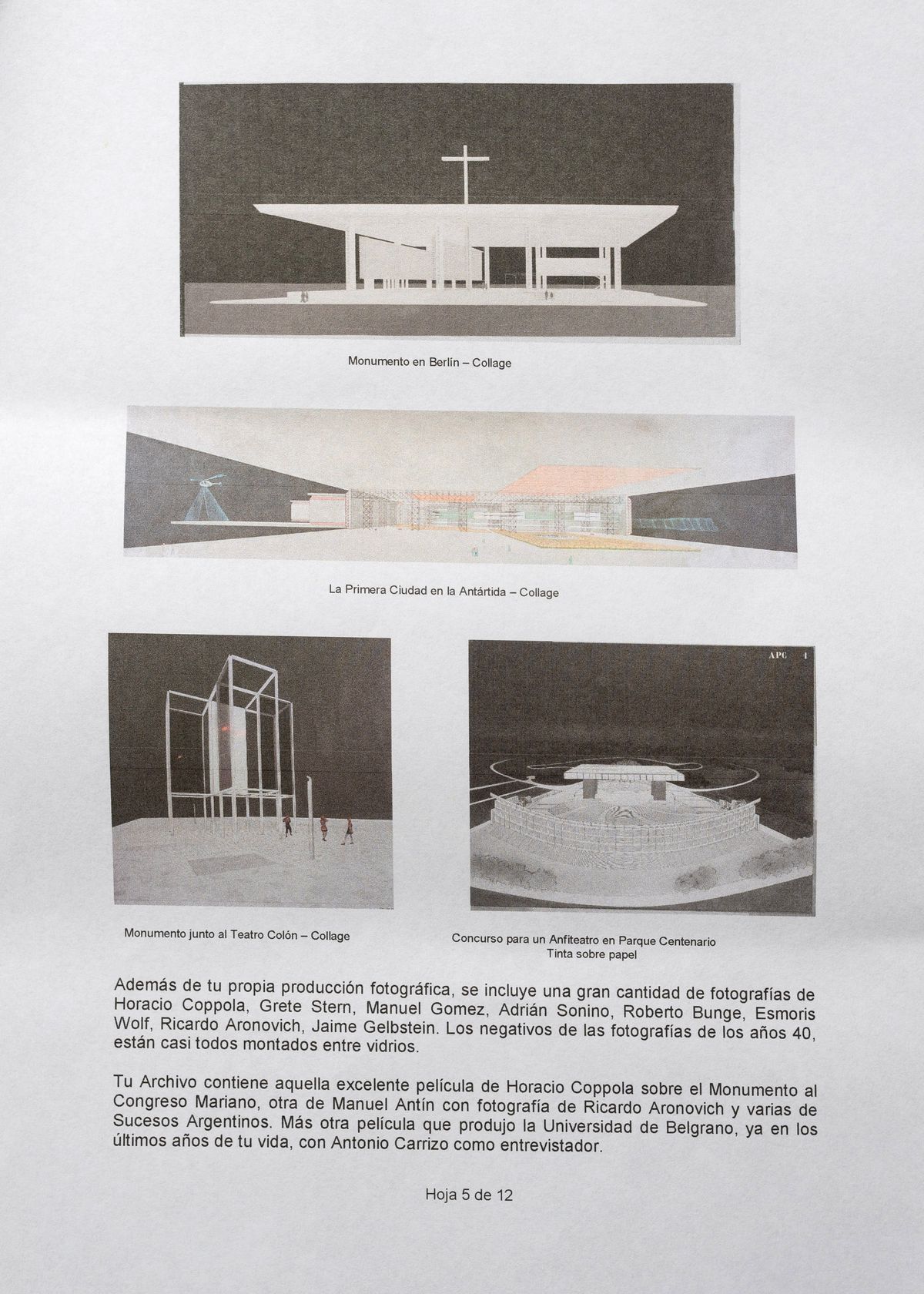

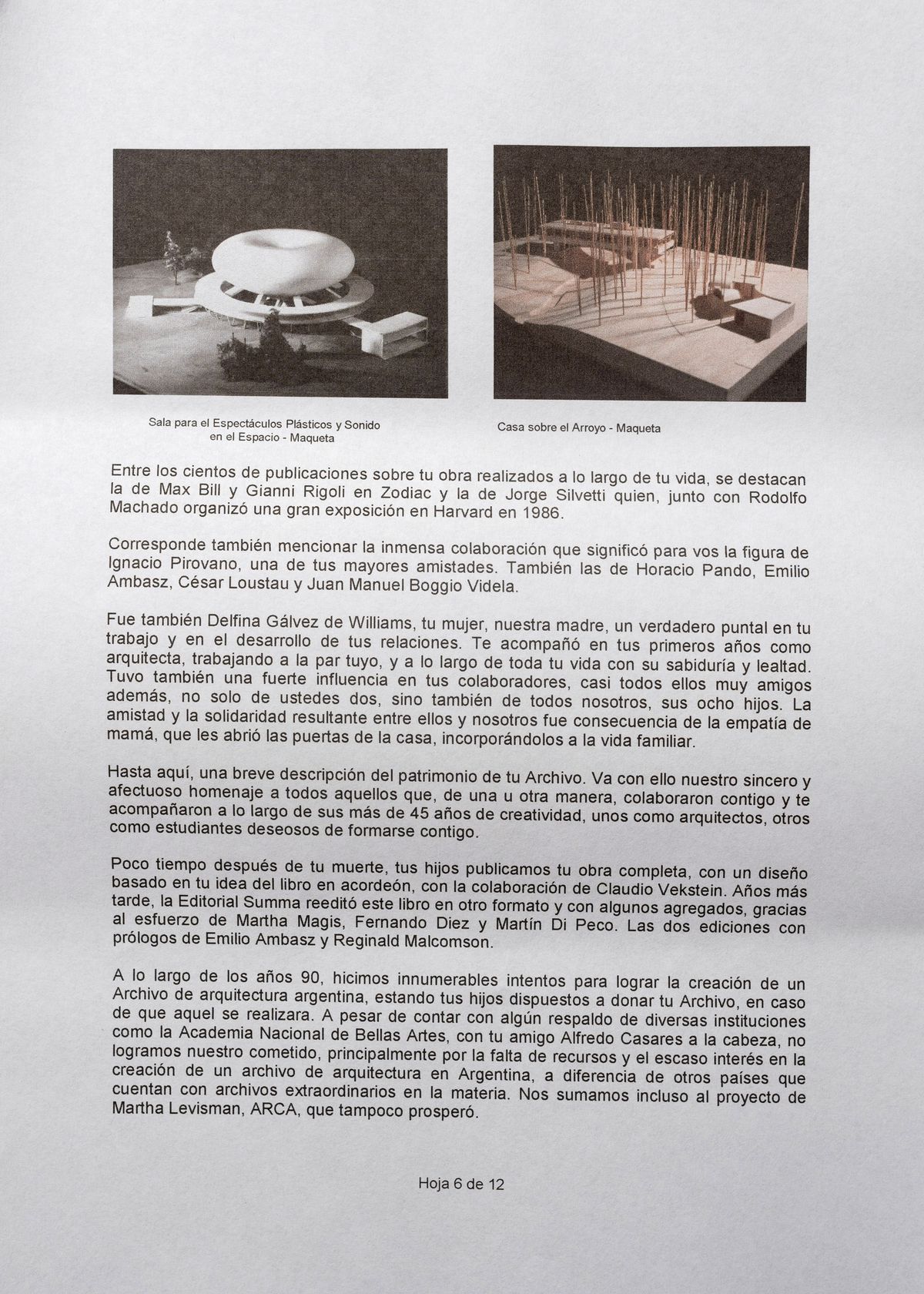

Exceptional among this principal collection of plates that you left us are the plans for Bridge House, the work on which importantly involved Delfina, your wife, our mother; plans for Houses in Space, with plates painted by Mama; plans for Suspended Office Building, designed with César Janello, Colette Boccara, and Jorge Butler; wonderful collages for the Hall for Visual Spectacles and Sound in Space; images of House in Pereyra Iraola Park, also painted by Mama; images of the Hospitals in Corrientes, aided by Jaco Saal and Helvidia Toscano, including the latter’s remarkable perspectives in enamel paint; works from the early sixties, done with the help of then students Emilio Ambasz and Norberto Benvenuto; splendid large-scale collages illustrating the various shell vault projects with various applications, which involved Luis Santos, Norberto Steindl, Eduardo Leston, and Santiago Bonfanti; and large collages for the Church in Berlin and the Iggam Factory.

Other plates and collages in this great collection represent the project for the Apartment Building in Belgrano, designed with a team led by Juan Trouilh; the Cross in the River, completed with the participation of Eugenia Berner Arenaza, Susana Foutel, and Ricardo Baumgarten, with the immensely important structural assistance of the studio Leonhardt und Andrä of Stuttgart, its team led by Leonhardt himself and his engineers Wilhelm Zellner and Reiner Saul; and the project for the City in Antarctica that was produced with the same team, with the collaboration of your friends Mario Payssé Reyes and Reginald Malcolmson on the “The City that Humanity Needs.”

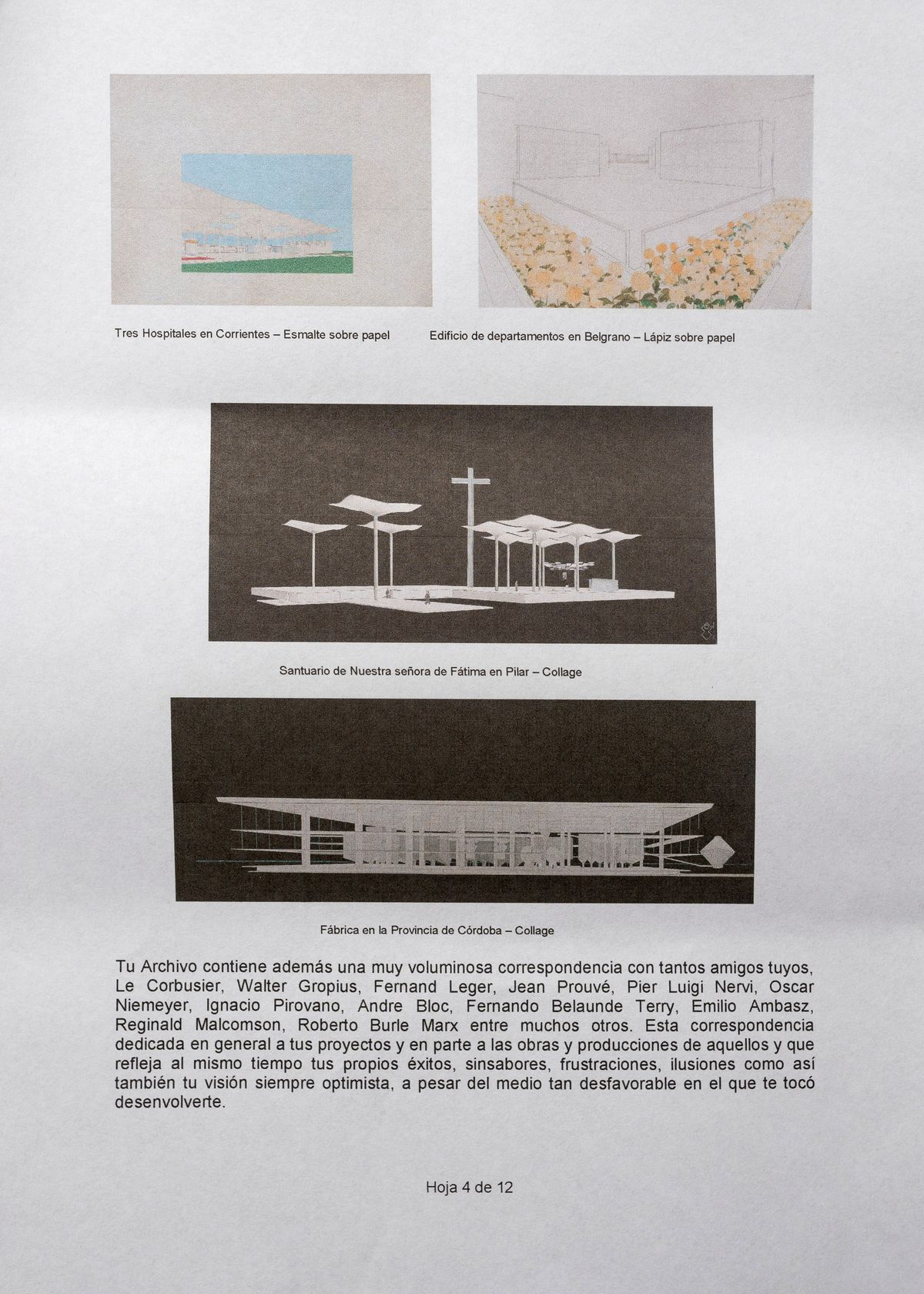

In addition to the original models that you produced, the archive includes a splendid model of one of the Hospitals in Corrientes produced by Raquel Peralta Ramos—the daughter of Raquel Palomeque and wife of Horacio Coppola—and a large model of Bridge House that includes the complete site and the Service Pavilion, produced by another of your students, Claudio Vekstein, for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

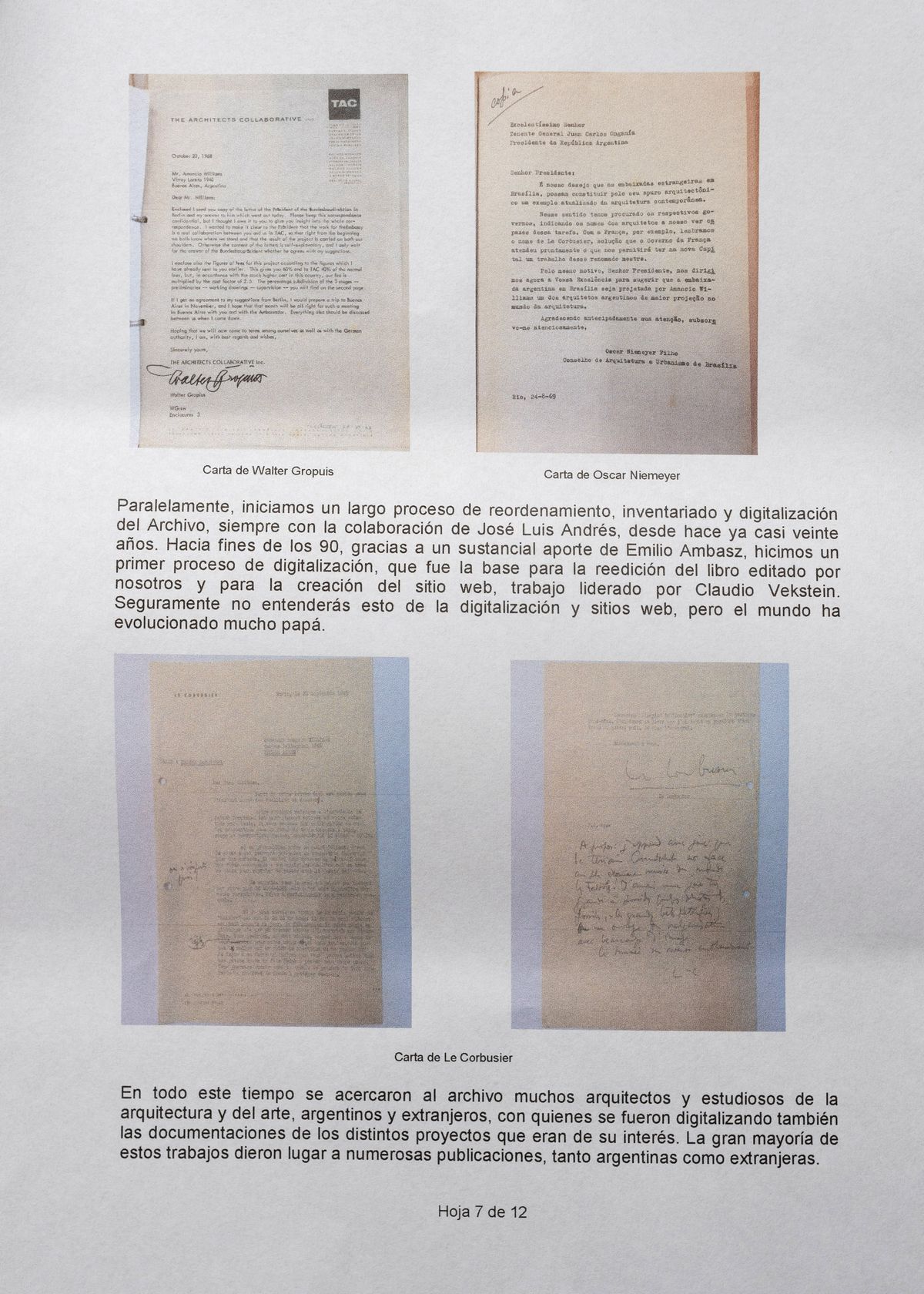

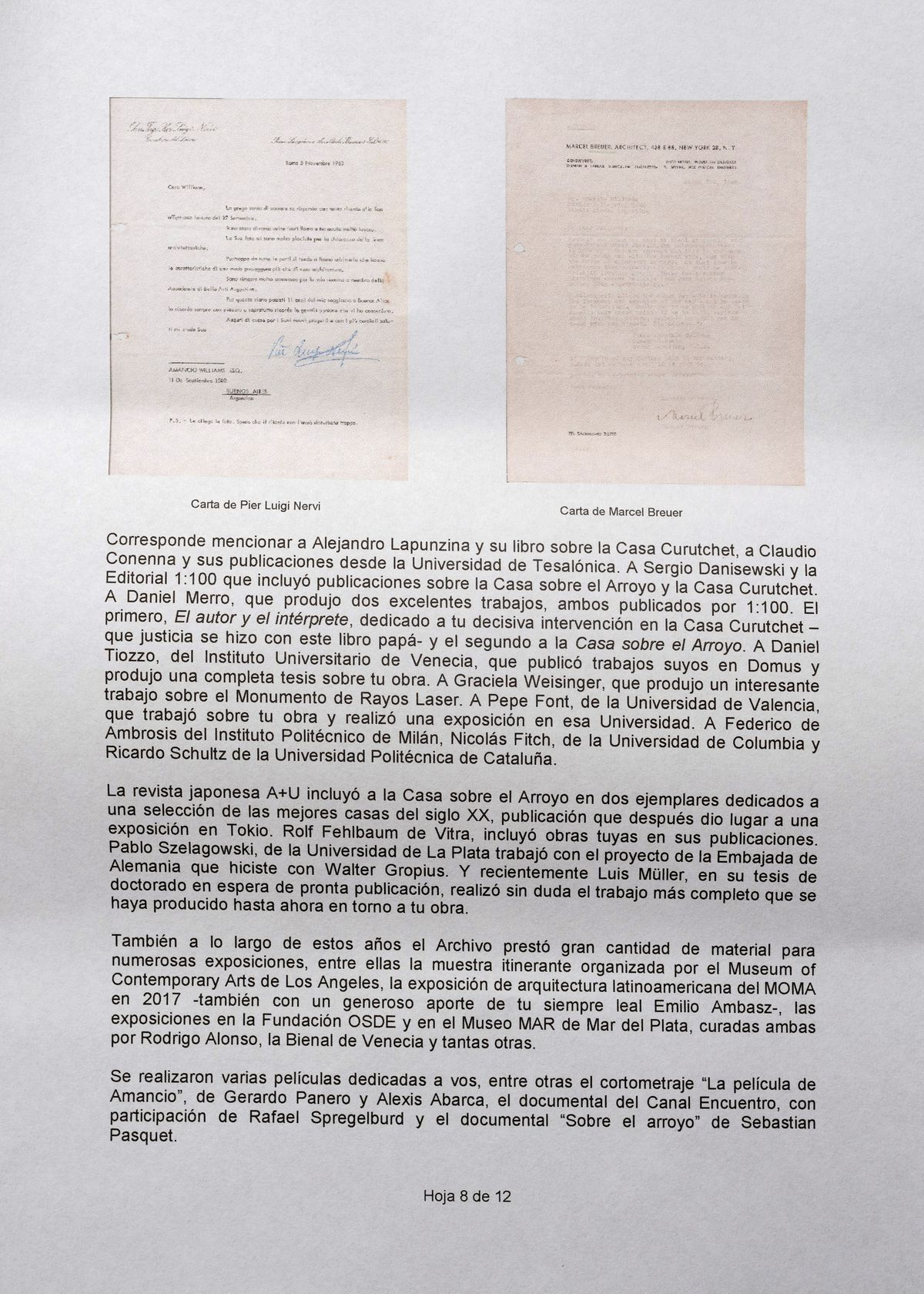

Your archive also contains a very voluminous collection of correspondence with your many friends—Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Fernand Léger, Jean Prouvé, Pier Luigi Nervi, Oscar Niemeyer, Ignacio Pirovano, André Bloc, Fernando Belaúnde Terry, Emilio Ambasz, Reginald Malcolmson, Roberto Burle Marx, and many others. This correspondence was devoted, broadly, to your projects and, in part, to the work and productions of the others that also reflected your own successes, disappointments, frustrations, and hopes, as well as your ever-optimistic outlook, despite the unfavourable environment in which you had to work.

As well as your own photographic work, there are many photographs by Horacio Coppola, Grete Stern, Manuel Gómez, Adrián Sonino, Roberto Bunge, Wolf-Esmoris, Ricardo Aronovich, and Jaime Gelbstein. The negatives of the photographs from the forties are almost all mounted between glass.

Your archive contains Horacio Coppola’s excellent film about the Monument to the Marian Congress, another by Manuel Antín with photography by Ricardo Aronovich, several films of Argentinian events, and a film produced during the final years of your life by the University of Belgrano with Antonio Carrizo as your interviewer.

Of the hundreds of publications about your work produced during your lifetime, particular mention should be made of those by Max Bill and Gianni Rigoli at Zodiac, and by Jorge Silvetti, who, together with Rodolfo Machado, organized a big exhibition at Harvard in 1986.

Also worthy of mention are your priceless collaborations with Ignacio Pirovano, one of your greatest friends, along with Horacio Pando, Emilio Ambasz, César Loustau, Juan Manuel Boggio Videla—

And, finally, Delfina Gálvez de Williams, your wife, our mother, who was an absolute mainstay in your work and in the development of your relationships. She accompanied you, in your early years, as an architect working alongside you and, throughout your life, with her wisdom and loyalty. She was also a big influence on your collaborators, almost all of them very close friends not just of the two of you but of all of us, your eight children. The resulting friendships and solidarity with them was a consequence of Mama’s empathy, which opened the doors of the house to them, drawing them into family life.

Thus far, I’ve given a short description of the legacy contained within your archive. It carries a sincere and affectionate homage to all those who, in one way or another, collaborated with you and accompanied you throughout your over 45 years of creativity, some as architects and others as students eager to train with you.

Shortly after your death, in collaboration with Claudio Vekstein, your children published your complete works in a format based on your idea for an accordion book. Years later, Summa republished this book in another format and with some additions, thanks to the efforts of Martha Magis, Fernando Diez, and Martín Di Peco. Both editions include forewords by Emilio Ambasz and Reginald Malcolmson.

Throughout the nineties, we made countless attempts to help create an archive of Argentinian architecture, and we were willing to donate your archive if the endeavour were successful. Despite receiving some support from various institutions such as the National Academy of Fine Arts, which your friend Alfredo Casares helmed, we failed in our mission, due mainly to an absence of funding and a lack of interest in creating an archive of architecture in Argentina, unlike other countries with outstanding archives in this field. We even joined Martha Levisman’s project, ARCA, which did not prosper either.

At the same time, we embarked on a long process that has lasted almost twenty years now of reordering, inventorying, and digitizing your archive with the constant collaboration of José Luis Andrés. Toward the end of the nineties, thanks to a substantial contribution by Emilio Ambasz, we began the initial process of digitization, which was the basis for republishing the book and creating a website, an endeavour led by Claudio Vekstein. You will probably not understand all this about digitization and websites, but the world has changed a lot, Papa.

In all this time, the archive was consulted by many architects and students of architecture and art, from Argentina and beyond, who digitized the documentation of the various projects that were of interest to them. The vast majority of these consultations gave rise to numerous publications in Argentina and abroad.

I would like to mention Alejandro Lapunzina and his book about Curutchet House and Claudio Conenna and his publications at the University of Thessalonica; Sergio Daniszewski and Ediciones 1:100 with publications about the Bridge House and Curutchet House; Daniel Merro, who produced two excellent works, both published by Ediciones 1:100—the first, El autor y el intérprete, deals with your decisive design of Curutchet House–justice was done in this book, Papa—and the second is Casa sobre el Arroyo; Daniel Tiozzo, of the Instituto Universitario di Architettura in Venice, who published work in Domus and produced a complete thesis about your work; Graciela Weisinger, who wrote an interesting work about the Laser Ray Monument; Pepe Font, at the University of Valencia, who studied your oeuvre and organised an exhibition at his university; Federico Deambrosis of the Politecnico di Milano; Nicholas Fitch of Columbia University; and Ricardo Schultz of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

The Japanese magazine A+U included Bridge House in two issues devoted to a selection of the best houses of the twentieth century, which gave rise to an exhibition in Tokyo. Rolf Fehlbaum of Vitra included works of yours in his publications. Pablo Szelagowski, at the University of La Plata, worked with the project for the German Embassy that you designed with Walter Gropius. And recently, Luis Müller, in his soon-to-be-published doctoral thesis, has written the most complete study to date about your work.

In the course of these years, too, the archive loaned a great deal of material to numerous exhibitions, including the touring show organized by the Museum of Contemporary Arts, Los Angeles, the Latin American architecture exhibition at the MoMA in 2015 (which also included a generous contribution by your ever-loyal Emilio Ambasz), exhibitions at the OSDE Foundation and the MAR Museum in Mar del Plata, both curated by Rodrigo Alonso, the Venice Biennale, and many others.

Several films have been made about you, including the short film La película de Amancio by Gerardo Panero and Alexis Abarca, the Canal Encuentro documentary with the participation of Rafael Spregelburd, and the documentary Sobre el arroyo by Sebastian Pasquet.

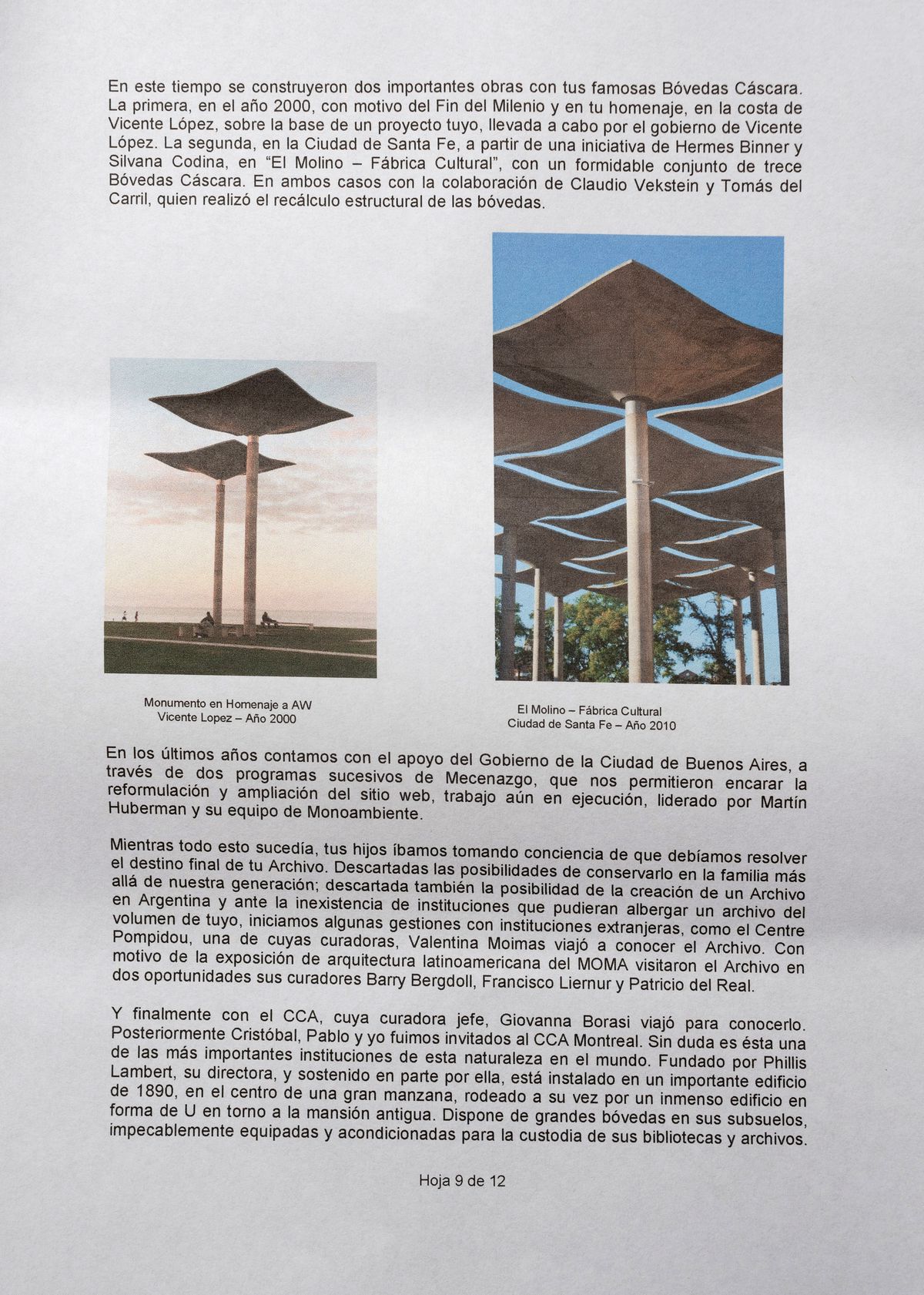

In this time, two major works with your famous shell vaults were built. The first, built in 2000 on the coast of Vicente López, was based on one of your projects and commissioned by the local government to mark the end of the millennium and as a tribute to you. The second, at El Molino Fábrica Cultural in the City of Santa Fe, was an initiative by Hermes Binner and Silvana Codina, with a formidable complex of thirteen shell vaults. In both cases, Claudio Vekstein worked with Tomás del Carril, who was responsible for the structural recalculation of the vaults.

In recent years, we have received the support of the City of Buenos Aires municipal government through two successive patronage programmes that have allowed us to reformulate and expand the website, a work still in progress, led by Martín Huberman and his team at Monoambiente.

While all this was happening, your children were becoming aware that we had to decide upon a final destination for your archive. Having ruled out the possibility of keeping it in the family after our generation, having also ruled out the possibility of creating an archive in Argentina, and faced with the non-existence of institutions that could house an archive of the volume of yours, we started negotiating with foreign institutions such as the Centre Pompidou, one of whose curators, Valentina Moimas, travelled here to see the archive for herself. On the occasion of the exhibition of Latin American architecture at the MoMA, the archive was visited twice by its curators, Barry Bergdoll, Jorge Francisco Liernur, and Patricio del Real.

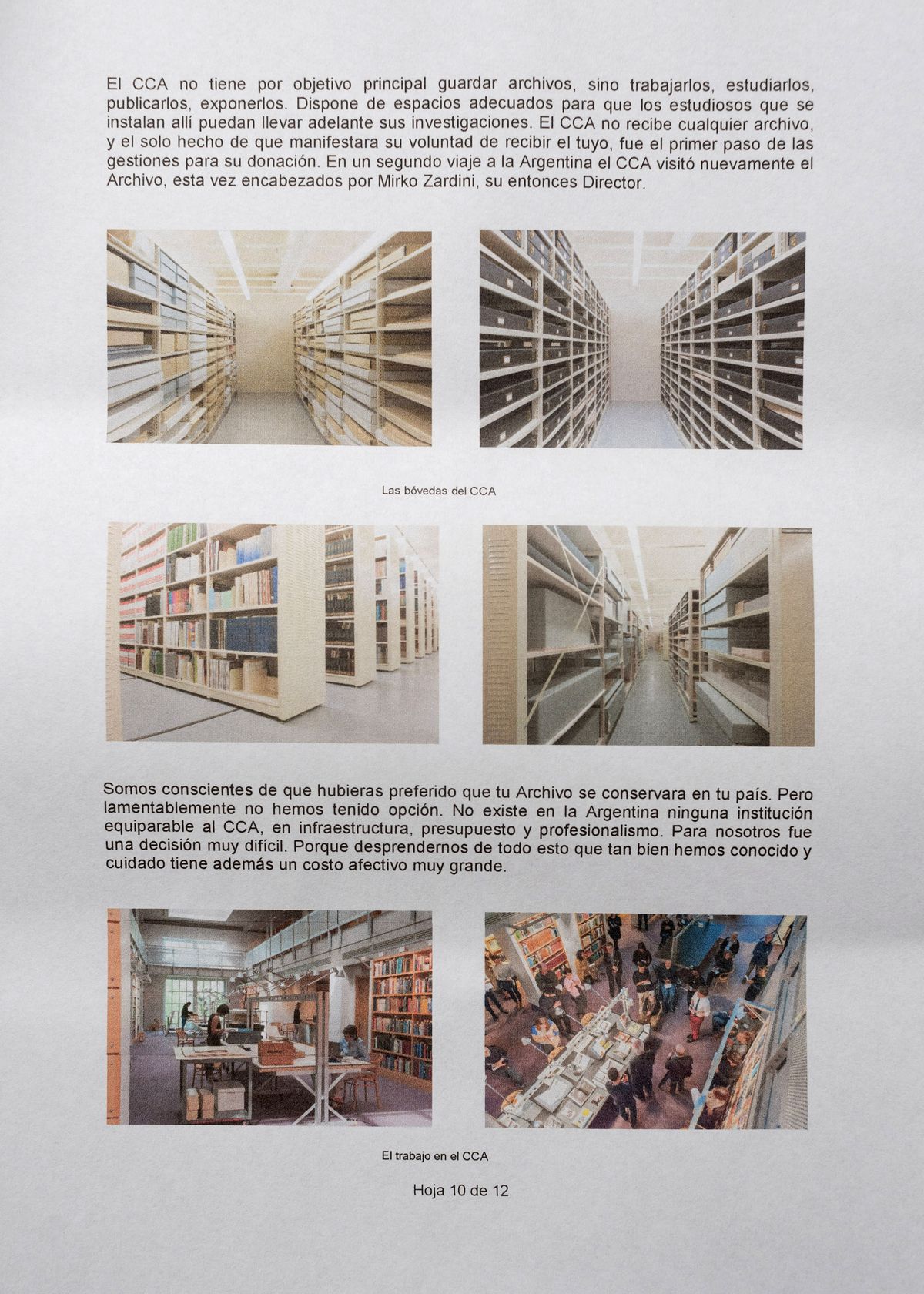

And, finally, the CCA’s chief curator, Giovanna Borasi, travelled to see your archive. Later, Cristóbal, Pablo, and I were invited to the CCA in Montréal. This is undoubtedly one of the leading institutions of this kind in the world. Founded by Phyllis Lambert, its first director, and partly supported by her, it is housed in an important building built in 1875 located at the centre of a large street block, with the old mansion surrounded in turn by a huge U-shaped building. It has large vaults in its basements, impeccably outfitted and equipped to preserve its libraries and archives. The principal aim of the CCA is not to keep archives, but to consult them, study them, publish them, and exhibit them. It has suitable spaces for students to settle there and carry out their research. The CCA does not accept just any archive, and the mere fact of expressing its willingness to receive yours was the first step in the negotiations for its donation. During a second trip to Argentina, the CCA made another visit to the archive, this time headed by Mirko Zardini, then Director.

We know that you would have preferred your archive to remain in your country. Sadly, we had no option. There is no institution in Argentina comparable to the CCA in terms of its infrastructure, budget, and professionalism. It was a very difficult decision for us. Letting go of all this, which we have cared for and come to know so well, comes at a big emotional cost.

We are so convinced by this decision that we have chosen not to keep any of the plates or drawings for ourselves. We wanted to keep the archive whole, as you always said it should be, as it was passed down to us and as we have increased it with everything added in these thirty years since your death. We know that taking anything from it would have affected the force and the value of the whole.

Finally, Papa, I would like to especially thank those who accompanied me in this long process. Starting with my brothers and sisters, Verónica, Florencia, Inés, Cristóbal, Gloria, Teresa, and Pablo, who spared no effort and took part wholeheartedly from the start. Clara Bel, who was, for many years, an effective counsellor to you and to me, as well as Norberto Padilla and Gustavo Fiorito. And my daughters Leticia and Cecilia, and Ana Meyer, my emotional mainstays.

I would like to end these reflections by quoting the words of the then-mayor of the City of Buenos Aires, Carlos Grosso, at the presentation of your book in 1990:

Let me recall two or three things about this great man. First, his obstinate persistence in creation and innovation. He was not afraid of change, of the future. He clearly identified the quintessence of tradition as a foothold for his next leap. A society in general like ours, rather timid toward some things, chose to describe his work with the word utopia since it could not deny him the authority and hierarchy of creativity and innovation. Because, with the word utopia, one can freeze the conducive effects of innovation. The word utopia takes us into the next century. And the second element that comes after consolidating respect for creativity and innovation, freezing it in utopia, is sanctification. And this sanctification brought with it frustration. Because it was so sacred that it was unworkable. It was so utopian that it was not of this time. It was so innovative that it was scary to undertake his projects. And so he found a third virtue that I would like to underline, which was his generosity in thinking permanently of projects for the community, seeing that he was reaching the end of his life, very sacred, very award-winning, very utopian, and very unbuilt. Perhaps, more than the tributes, more than a new page of sanctity, it would be good to reopen the debate, to take a good look at the projects of Amancio Williams, and to see whether now is the time to normalize his utopia.

And that is what your children are doing, dear Papa, by donating your archive in its entirety to the Canadian Centre for Architecture. We are ensuring its future, its conservation, and its dissemination. Just as we have kept it alive throughout the last thirty years, the CCA will keep it alive from now on.

Claudio Williams

Buenos Aires, February 2020