In absence of...adequate objects

Matthew Critchley, Hannah Rose Feniak, and Jia Gu on archival considerations

This article is the fifth in our “In absence of…” series, authored by the participants of our 2019 Toolkit for Today and introduced by Rafico Ruiz in this primer. In the following, Matthew Critchley reflects on losses that take place in translations, Hannah Rose Feniak considers the researcher’s position relative to the date of death of archival authors, and Jia Gu argues for the necessity of archiving architectural models.

In absence of…a possible translation

Matthew Critchley

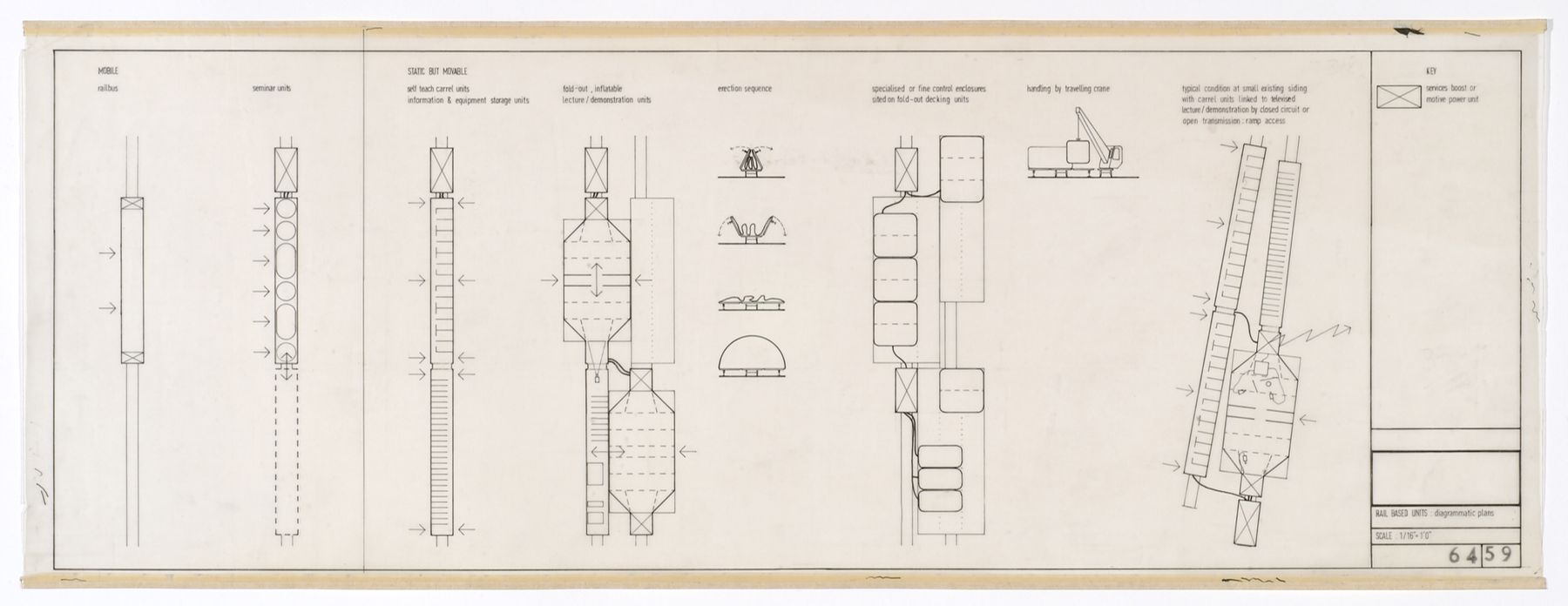

In our field, it is always worth rehearsing the argument that problems of translation are not the exclusive domain of the printed text. In architecture, such problems have their own particular inflection. As Robin Evans argues, in “Translations from Drawing to Building,” the architect is often in the curious position of not dealing with the object of their artistic production but with the distant proxies of drawings and maquettes, proxies which architects rarely treat as artistic objects in themselves.1 These problems are further compounded if we turn to the language we use to talk about architecture. In Words and Buildings, Adrian Forty highlights that modernism did not just involve an abstraction of form but also an abstraction of language. Forty explains that, through the language of modernism, the complexity of the built artefact was reduced to a few fundamentals of abstract form.2 Such an abstraction of thinking reached an apotheosis in the work of architects such as Cedric Price, whose designs resolved themselves through a taut visual economy. While modernism as a style has long since passed into history, the inheritance of modernist language remains a salient influence. It can act as a kind of filter that levels out all the haptic and figurative complexities of the built artefact and translates it into a reduced set of formal markers.

These inherent problems in the discipline are compounded by a broader and more recent problem in academia. Despite the geographic breadth of research topics, the anglophonic dominion has published polyphonic thinking out into the periphery of academic production. Of course, research and theory travel quickly through the English filter, but it is a filter, and the consequences of such a levelling are difficult to determine when one is working within it. The archive is often a repository of an extraordinary wealth of linguistically diverse material. Though diligent scholars will try their best to accurately translate the concepts that they encounter within the archive, translation remains a problematic process, not because meaning is “lost” but, more alarmingly, because meaning is transformed.

Fortunately, there are many writers and scholars who are cognisant of the manifold nature of these problems. They each outline separate and distinct conceptual traditions, ones which should not be ignored in any kind of serious archival investigation, architectural or otherwise. One such writer is the Haudenosaunee writer Alicia Elliott, who in her essay “A Mind Spread Out on the Ground,” explains that the lexicon of clinical psychology fails to capture the Indigenous experience of depression. She describes how terms such as “exogenous depression” and “endogenous depression” fail to account for the collective trauma that is simultaneously experienced at the personal, social, and intergenerational levels. The incongruent nature of such terms is made palpable in English, Elliott explains. The Haudenosaunee words most commonly attributed to depression are wake’nikonhrèn:ton and “wake’nikonhra’kwenhtará:’on*, which respectively mean “a mind suspended” and “a mind spread out on the ground.” As Elliott attests, the Haudenosaunee words demonstrably convey an experience, which cannot be captured within the reticulated labels of clinical practice.3

In a different register, Yijing Zhang also demonstrates the incongruity between separate epistemic traditions in her article “Is logos a proper noun? Or, is Aristotelian Logic translatable into Chinese?” Through a careful analysis of translations of the term “logos” into Chinese, Zhang teases out the fundamental philosophical problems inherent in attempts to translate Western philosophy into Chinese, leading her to reinforce the critique of the universality of Western logic. In concluding, she reframes the problem of untranslatability in a way that could extend across all fields of research including architecture: “As concerns the philosophical exchange between Europe and the East, untranslatability is not opposed to translation but is the process of translation itself.4

-

Robin Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building,” AA Files, no.12 (Summer 1986): 3–18. ↩

-

Adrian Forty, Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture (London: Phaidon, 2000), 19–27. ↩

-

Alicia Elliott, “A Mind Spread Out on the Ground,” in A Mind Spread Out on the Ground (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2019), 9–11. ↩

-

Yijing Zhang, “Is logos a proper noun? Or, is Aristotelian Logic translatable into Chinese?,” Radical Philosophy 2, no. 4 (Spring 2019). ↩

In absence of… a date (of death)

Hannah Rose Feniak

“But the question of the fragment in architecture is very important since it may be that only ruins express a fact completely…I am thinking of a unity, or a system, made solely of reassembled fragments… But it happens that historical obstacles - in every way parallel to psychological blocks or symptoms - hinder every reconstruction.”1

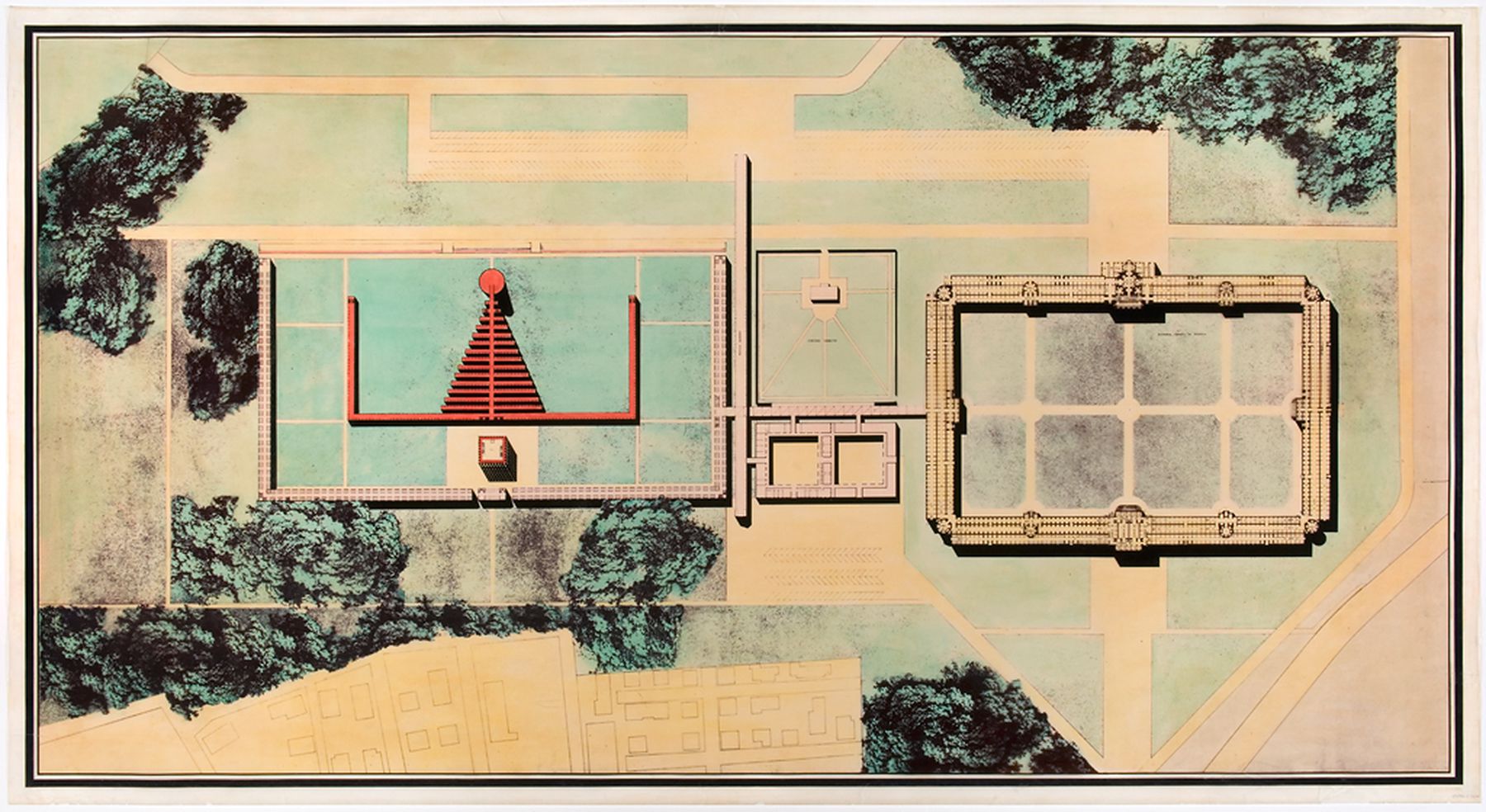

Aldo Rossi’s canonical San Cataldo cemetery has been dubbed the birthplace of architectural postmodernism. Famously, in lieu of a graveyard, the project proposes a city for the dead. In the cemetery, located in Modena, the deceased are suspended in an architectural space that is set apart from the lived present. A prominent ossuary cube marks the entrance to the site. Roofless and standing without windows, doors, or even floors, Rossi’s “house for the dead” does not offer the shelter or protection that are often the primary functions of homes for the living; the graves housed in San Cataldo are left exposed to the elements and put on display for the gaze of the city’s living visitors. Read allegorically, the dwellings provided for the dead residents of Rossi’s cemetery parallel the chronopolitical dimensions of contemporary archival and historical practices.

Archives are premised on a specific material conception of the relationship between past and present and between material object and researcher. Presumably, archives act as houses in which objects are laid to rest to be preserved in unchanging perpetuity. Like the afterlives of the dead who reside in Rossi’s cemetery, when an object enters an archival institution, it is assumed to no longer hold the same agency that it held while it was in circulation amongst the living and to have transformed into an inert artefact, inextricably tethered to the moment of its creation or the context of its production.

When an artefact is mobilized as evidence to an argument, it is often implied that the artefact, allocated the authority of objectivity, is an empirical fact, to which the researcher brings a subjective interpretation. Yet, once an object is catalogued as part of an archive, it continues to exist within an active system of signification and re-signification, mediated, for instance, by institutional values or disciplinary trends, before the researcher even arrives.

The relationship between a researcher and archival object thus hinges on a specific construction of the relationships between space and time and between humans and matter. Yet, the very conception of this temporality can also be understood as a contested site of power. Indeed, the assumption that a person’s date of death marks the end of their life is a touchstone of Western metaphysics (dualism), and this bias is reified judicially via post-mortem rights, which define the nature of our engagement with the documents and objects that survive the deceased vis-à-vis consent and intellectual and property law.

In my own research, I have often wondered how my position relative to an individual’s date of death affects the way that I interpret their archive: do I consider documents differently if they belong to a living person with whom I can (ostensibly) converse to “fill in” the missing information? How do such assumptions reinforce the notion that archival objects are of a particular time rather than continuing to exist in time?

Not all cultures share the same metaphysical conceptions of the relationship between life and death, or views on individual ownership and material culture. Take for instance the Swahili concept of zamani, which, as explained by literary scholar Jacqueline Jones Royster, refers to a temporal framework wherein a person, after dying, continues to exist in the present as a part of an immortal collective that engages with the living members of the community.2 Contrary to dominant understandings of the archival document as a static historic artefact, frozen outside of the flow of linear time, an active relationship exists between the object and the person, community, or organization with whom it is associated.

For Rossi, the physical past remains in a continuous but ever-changing dialogue with the present. Ruins, as fragments of the built past, are read through the interpretative lens of the contemporary architect and translated into modern aesthetics through modern building techniques. And so, “history” is continuously reconstituted and, thus, plods on. I wonder about the implications of acknowledging the situatedness of archival material and the authority that institutions invest in these objects or their previous owners after they are deceased. Not only do specific archival practices contribute to the canonization of certain individuals and works, while obscuring the histories of others, the ways in which we approach archival objects reinforce epistemological biases.

What would it mean to consider an archival object not as an inert fact but rather as an interlocutor? Could a discussion of reciprocity with marginalized cultures about non-normative concepts of time or knowledge practices contribute to more nuanced global histories? How could this change the types of and the ways that stories are told?

-

Aldo Rossi, The Scientific Autobiography (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1981), 4. ↩

-

See Jacqueline Jones Royster, “Reading Between the Lines,” in Traces of a stream: literacy and social change among African American women (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000), 78–93. For further discussion of the relevance of this concept to the ethics of archival research, see Heidi McKee and James Porter, “The Ethics of Archival Research,” College Composition and Communication 64 no. 1 (2012): 59–81. ↩

Recommended readings

• Brothman, Brien. “Archives, Life Cycles and Death Wishes: A Helical Model of Record Formation.” In Archivaria: Special Section on Archives, Space and Power 61 (Spring 2006): 235–269.

• Ghirardo, Diane. “The Blue of Aldo Rossi’s Sky.” AA Files 70 (2015): 159–172.

• Huebener, Paul. “Canadian Time: Reading the Politics of Time in Canadian Culture.” In Timing Canada: The Shifting Politics of Time in Canadian Literary Culture. Montréal: MQUP, 2015.

• McKee, Heidi A., and James E. Porter. “The Ethics of Archival Research.” College Composition and Communication 64, no. 1 (2012): 59–81.

• Rabe Smolensky, Kirsten. “Rights of the Dead.” Arizona Legal Studies Discussion Paper, nos. 6–27 (9 March 2009).

• Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Traces of a stream: literacy and social change among African American women. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000.

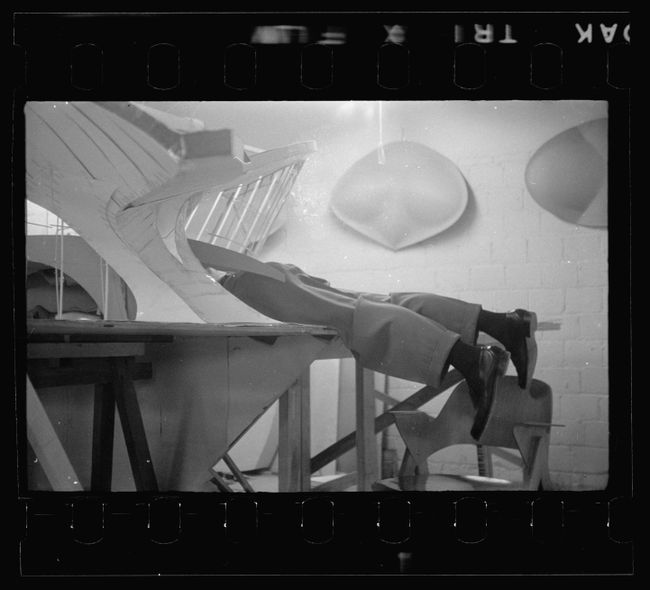

John F. Waggaman, portrait of Frederick Kiesler at work, c. 1965. Gelatin silver print, 34.3 x 27.3 cm. Museum of Modern Art. Digital Image © 2020 MoMA, N.Y. Photo © Estate of John F. Waggaman.

In absence of…model archives

Jia Gu

Consider two familiar, nearly canonical images from the history of architects and their models: one documenting Frederick Kiesler working on a plaster model of his Endless House, a notorious work of sculptural architecture, and the second, Balthazar Korab’s famous photograph of Eero Saarinen stuffed inside the paper model for the Trans World Airline (TWA) Flight Center with his (at least given this era, we can presume “his”) well-pressed slacks and black loafers emerging from the belly of the model. It is generally accepted that the images of both architects and their models capture a moment of architecture in progress, an act of design, a snapshot of a process that we cannot quite access through our exteriority as future viewers, but one which we understand to be vital to the production of architecture.

In the photograph of Kiesler, the architect has manually crafted an amorphous architecture, which we know to be the Endless House. We can clearly see the work that Kiesler is “doing”, the manual-ness of his labour: the architect is holding a spatula to apply concrete to an armature of wire mesh. The model’s form is shaped before the concrete appliqué goes on; the cavernous mesh house is held up on chains to approximate a shape that is then hardened to concrete. Everything about this image presents Kiesler as a genius artist at work in a messy workshop, crafting a sculptural masterpiece. On his head a black beret, almost a cliché and his body is coiled to meet the ground, on which splatters of plaster permanently settle as he works. This is an image of a working artist in his messy production space, of the architect working solely and individually on his model as sculpture.

In many ways, the second image of an architect at work is similar to the first—a document of Saarinen labouring over the production of the model of the TWA Flight Center. Like Kiesler, Saarinen designed the flight centre through a modelling-first approach, iteratively shaping and forming the body of the airport as a model before drawing it. Like Kiesler, Saarinen too is swallowed up by his model. At the times of their being photographed, both the TWA Flight Center and the Endless House models are buildings-to-be, not yet real and not yet realized. They were both designed to be constructed in concrete, a seemingly fluid and formless material of industrial production. Unlike the Endless House model, in which plaster approximates concrete fluidity, the TWA Flight Center model approximates its material future with strips of paper. Its geometric form is reduced or reducible to ruled surfaces, mathematically precise and describable through controlled curves.

Yet this mathematical precision is itself theoretical: we don’t know how Saarinen moved dimensional information out of the scale model into measured construction drawings. The messy edges of the paper and seams between strips suggests a haphazardness to the model’s construction and that Saarinen’s approach is closer to that of hand-crafted sculpture than dimensioned construction. Furthermore, unlike Kiesler, whose manual labour is evidenced in the spatula tool he that he holds, the labour of the architect in the second image is obscured. We don’t quite see what he is doing, what he is building, or what his methods and tools are.

In looking at these photographs, we are struck by a naïve question: when does the model become a method? Specifically, how does the practice of constructing a physical, scaled, material object come to stand in for an act of design? What difference does it make to our understanding that one model is produced entirely through the sculptural expression of an architect’s hand, while the other attempts to ascertain mathematical accuracy and a system of reasoned construction through methods that are decisively manual and imprecise? If the model in the first image documents a design process that approximates sculpture, how can the model in the second be categorized? Is it sculptural craft, or is it scientific method?

The TWA model no longer exists. As is the case of most architectural models, those produced in Saarinen’s office were largely considered disposable and were, therefore, not preserved. In order to describe, contextualize, and interpret the “conditions of existence” of a cultural formation (such as postwar modelling practices), we must approach the historical record as archaeologists, reconstructing and interpreting data in fragments. We must do so with the understanding that textual and visual sources are themselves fragmentary captures of the haptic, material, and procedural conditions of modelling. Thus, research on models involves reading what is present in the archive to describe the purposes and procedures of absent objects.

Recommended readings

• Bredekamp, Horst, Vera Dünkel, and Birgit Schneider, eds. The technical image: a history of styles in scientific imagery. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2015.

• Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.

• Daston, Lorraine. Things That Talk: Object Lessons from Art and Science. New York City and Cambridge, MA: Zone Books and The MIT Press, 2004.

• Myers, Natasha. Rendering Life Molecular: Models, Modelers, and Excitable Matter. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

• Puff, Helmut. Miniature Monuments: Modeling German History. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014.

• Smith, Pamela H. The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2004.

• Smith, Pamela H., Amy R. W. Meyers, and Harold J. Cook, eds. Ways of Making and Knowing: The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2014.