Siting the Settler Record

Ella den Elzen, Rafico Ruiz, and Camille Saade-Traboulsi locate the objects of settler colonialism

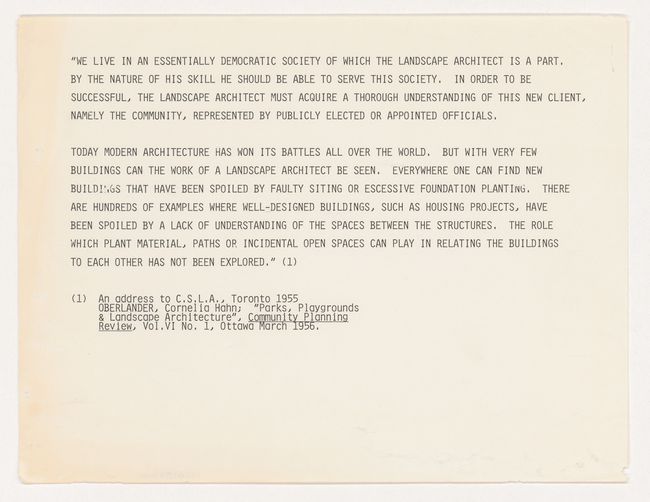

In what is now known as North America, design and architecture continue to play a role in the dispossession of Indigenous territories. These acts of settler colonialism occur through banal and widespread approaches to land, property, infrastructure, and notions of a taken for granted “common” ground (that is in fact land that has been cleared for settlement). Intentionally recognizing Indigenous lands while evaluating records of everyday design interventions can reveal spatial and power dynamics that often go overlooked in the rural, urban, and suburban contexts where architects work.

These CCA collection objects have been produced by settler architects across such sites of dispossession. To acknowledge this tension between these objects and their colonial legacies, their locations have been named to acknowledge the Indigenous territories they occupy. How should we read the settler archive for signs of dispossession? What forms of settler accountability can repositioning the lens through which we view these objects offer? How can we site the settler record with a view towards the restitution of land?

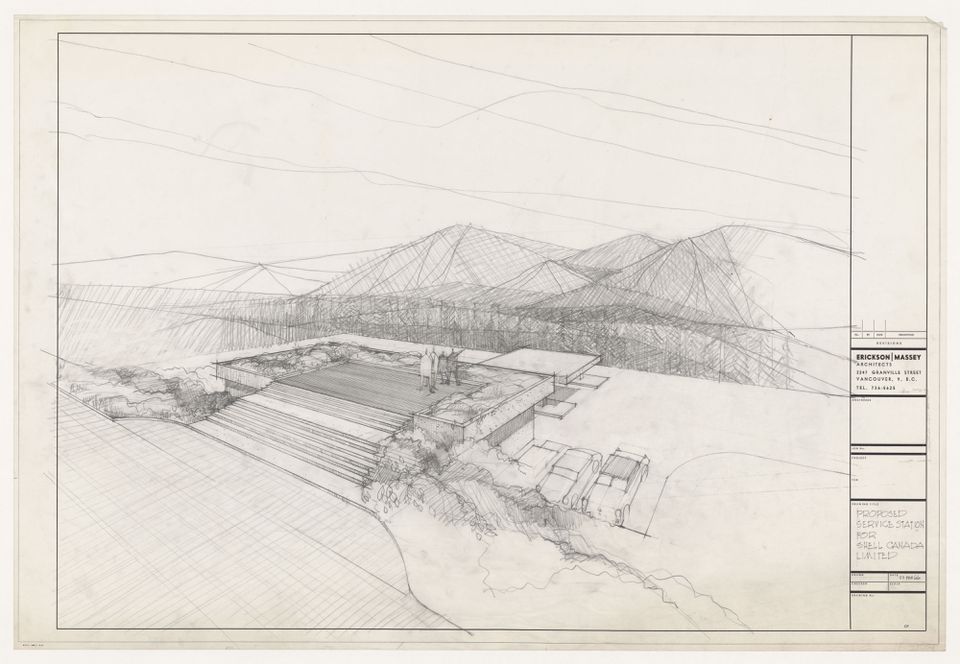

Arthur Erickson, a proposed service station for Shell Canada Ltd. at Simon Fraser University, unceded Coast Salish Territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh, and Kwikwetlem Nations, (Burnaby, British Columbia), 1966. Graphite and ink on transcluent paper, 61 × 91.4 cm. ARCH254965, Arthur Erickson fonds, CCA Collection © Estate of Arthur Erickson

Land is central to the practice of architecture, and sites, especially building sites, are often understood as neutral territory. This understanding enabled the colonial settlement of unceded Indigenous territories. Settler claims of dominion are often rooted in the dispossession of land, and architects, planners, and landscape architects continue to aid in the control of land through designing and building. This drawing, from Erickson/Massey’s design work for the Simon Fraser University campus in 1966, depicts a design for a Shell service station. Several student- and faculty-led protests had erupted over the aesthetics of Shell’s originally proposed design, which they saw as detracting from the campus’s coherence and connection with the surrounding mountain views. Erickson/Massey presented this alternative, in which a group assembles on the viewing platform of their proposed Shell station, looking over and standing on the unceded Territory of the Musqueam Nation.

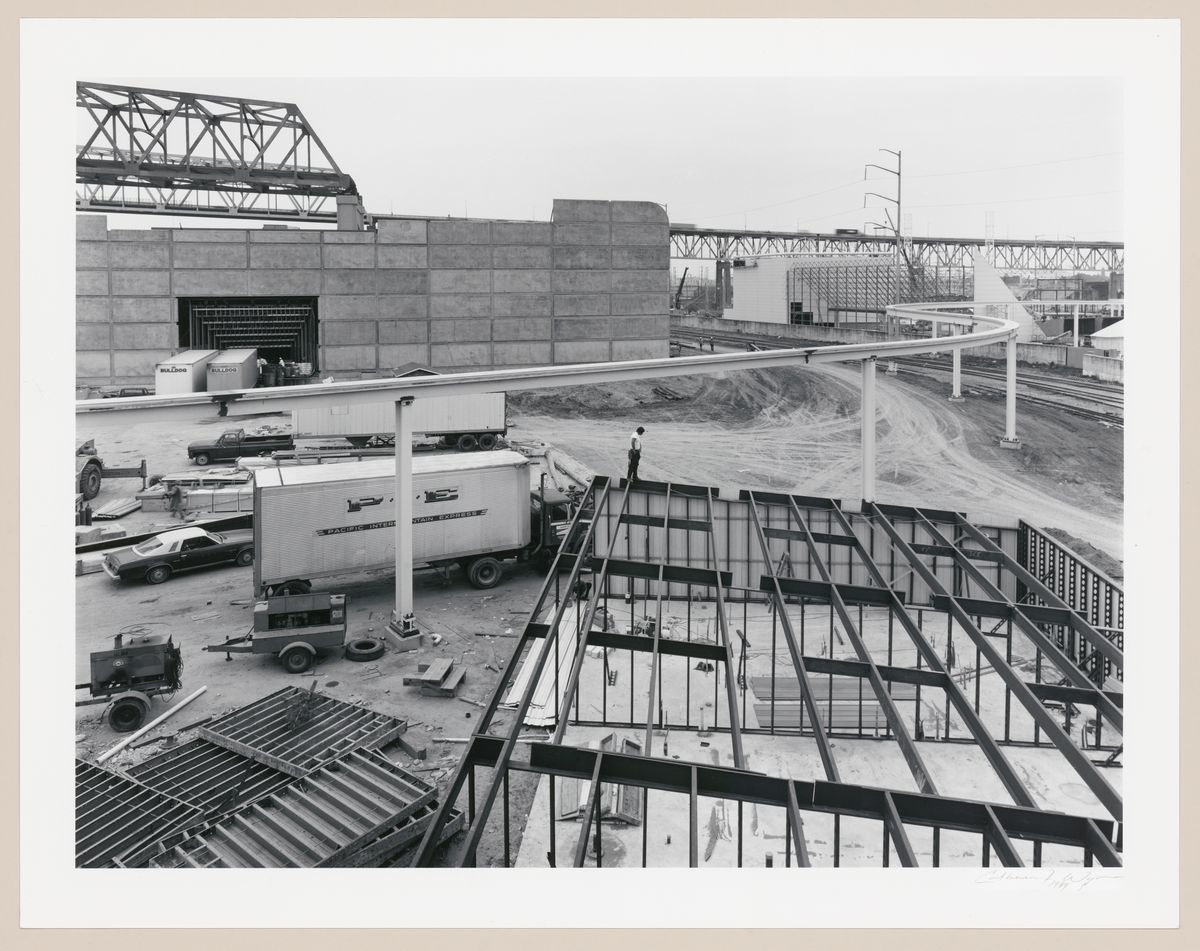

The vast continent of Turtle Island (North America) is connected through infrastructures that extend urban centres. The middle comes into focus when considering spaces that contain roads, railways, and other physical networks that connect centres of capital and commerce to peripheral settlements. The anonymity of the practice of architecture within these infrastructural contexts enables settlers in their consolidation of land into nations within geopolitical borders, subsuming Indigenous forms of land-based sovereignty.

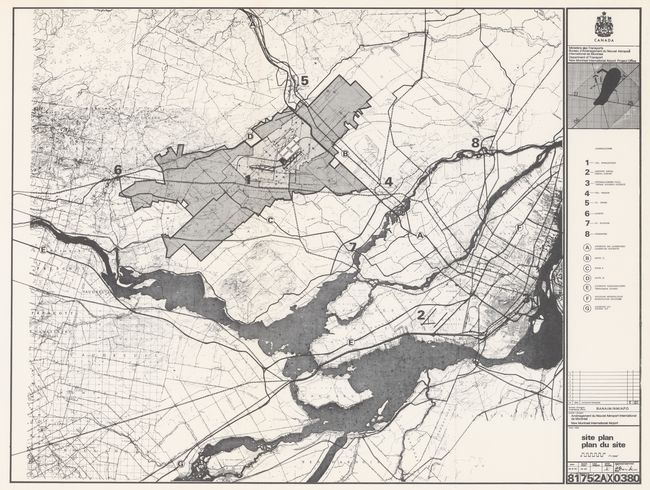

Consultants en Aéroports Internationaux de Montréal (CAIM), Regional Site Plan of the New Montréal International Airport inside Design Manual for the Ministry of Transport, 1970. Reprographic copy inside ring binder. ARCH284358, Papineau Gérin-Lajoie Le Blanc Architectes Fonds, CCA Collection.

PGL Architectes, presentation panel, Montréal International Airport Terminal, Unceded Territory of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, Algonquin, Haudenosaunee, Anishinaabe, and Mohawk Nations, (Mirabel, Québec), 1970-1972. Collage of cut out photographs and colour magazine pages on ink, coloured gouache and graphite pencil drawing, mounted on board. ARCH250432, Papineau Gérin-Lajoie Le Blanc Architectes Fonds, CCA Collection © PGL Architectes

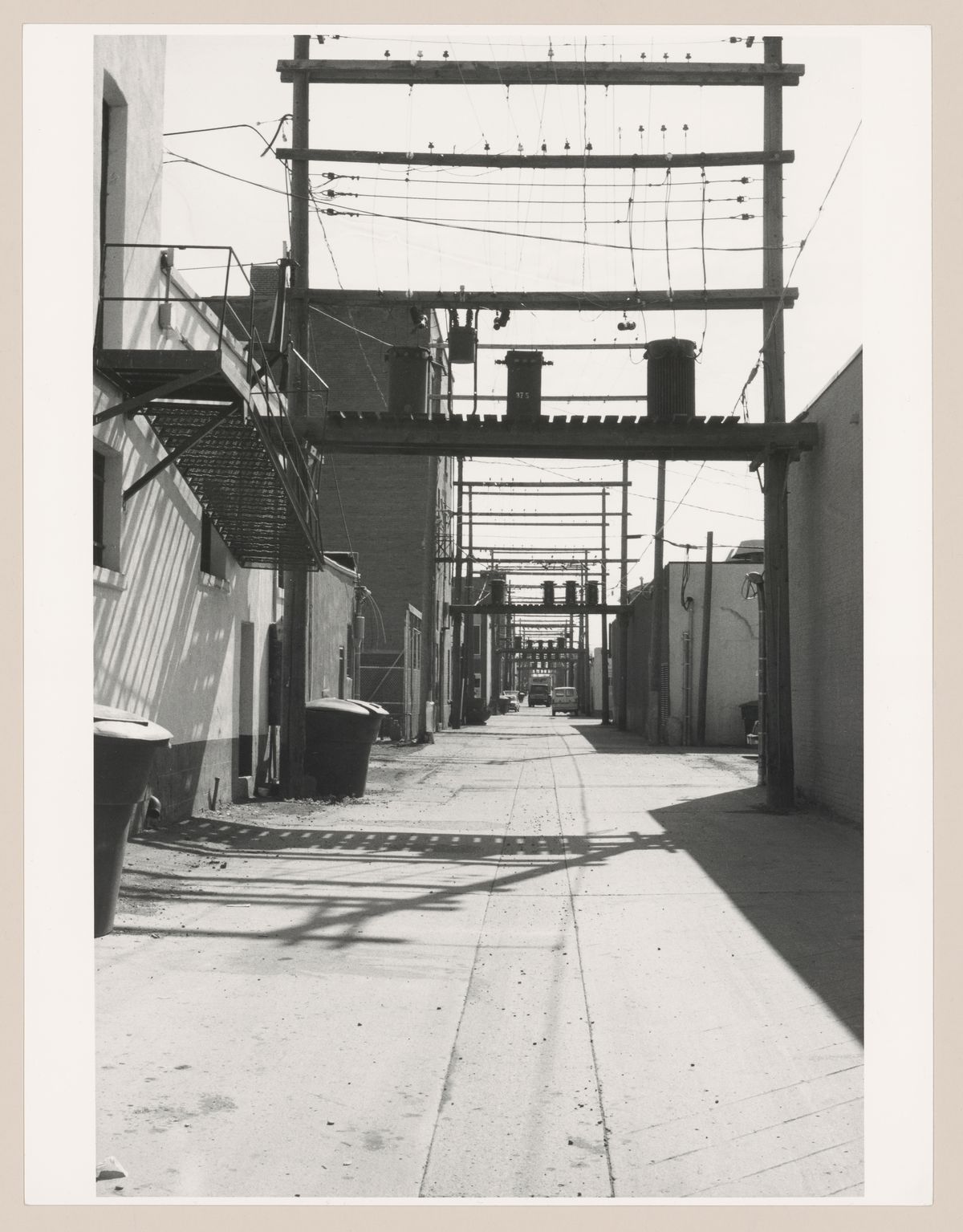

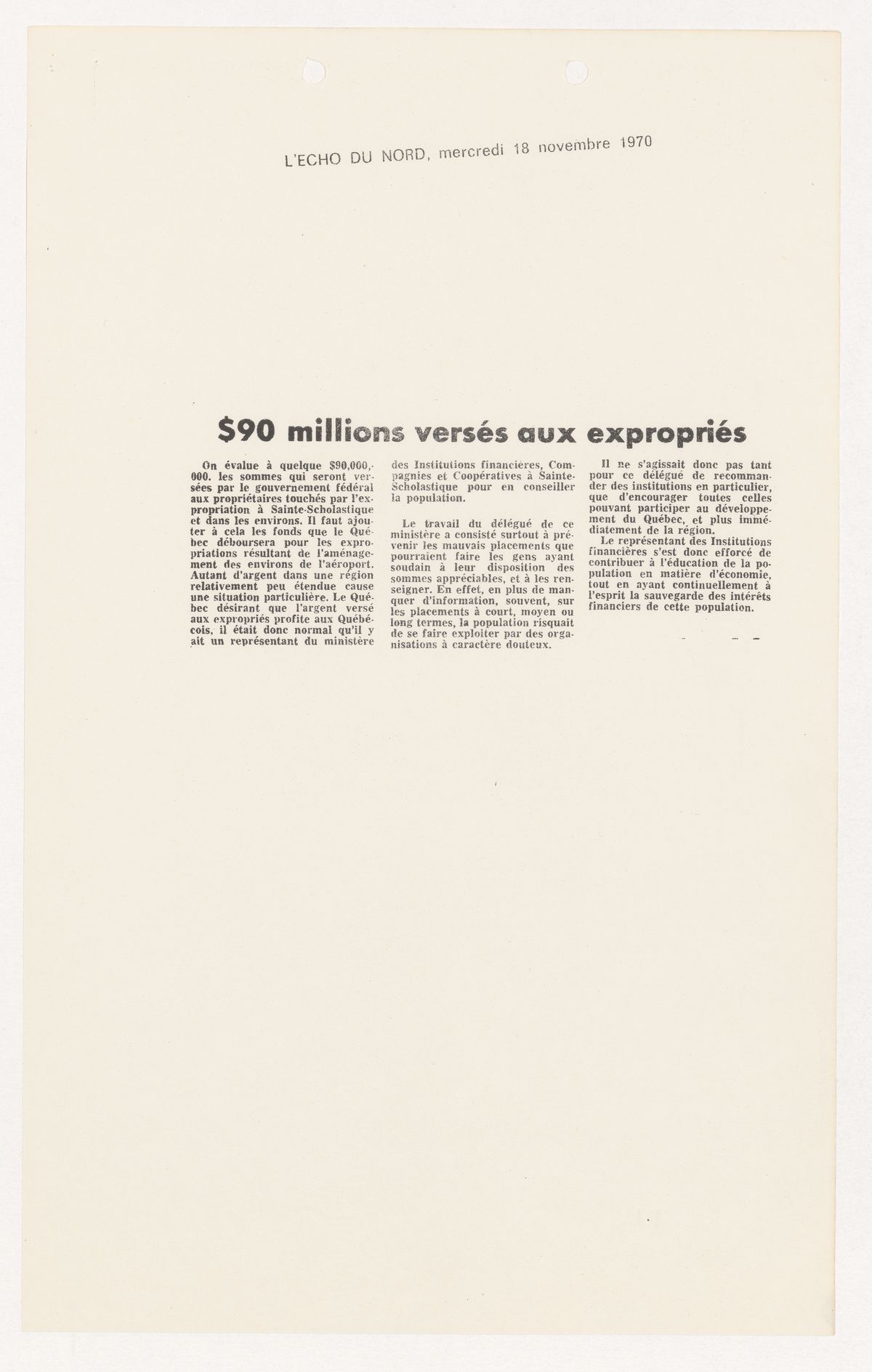

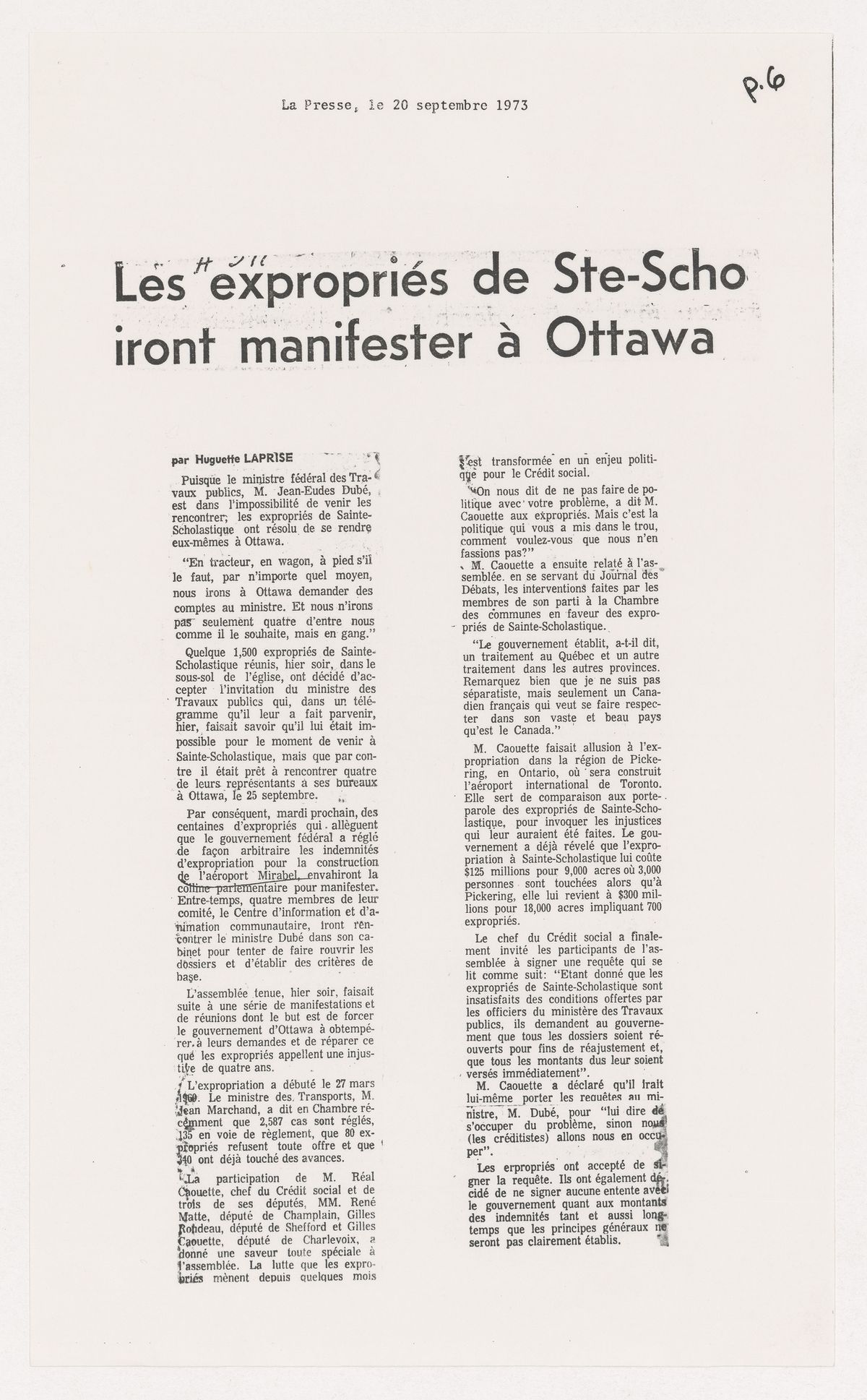

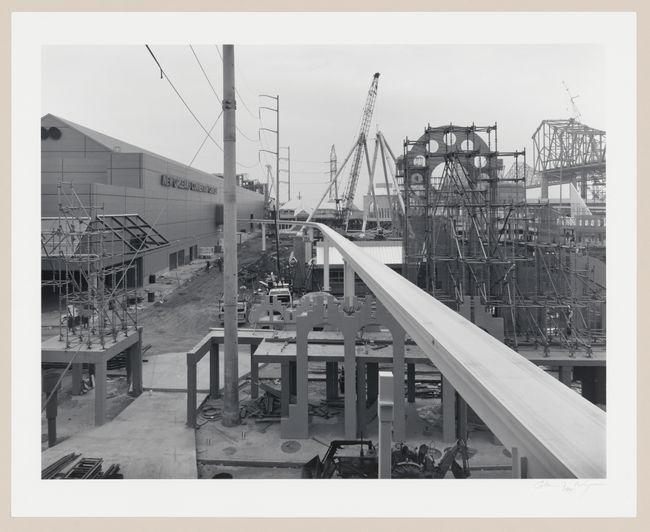

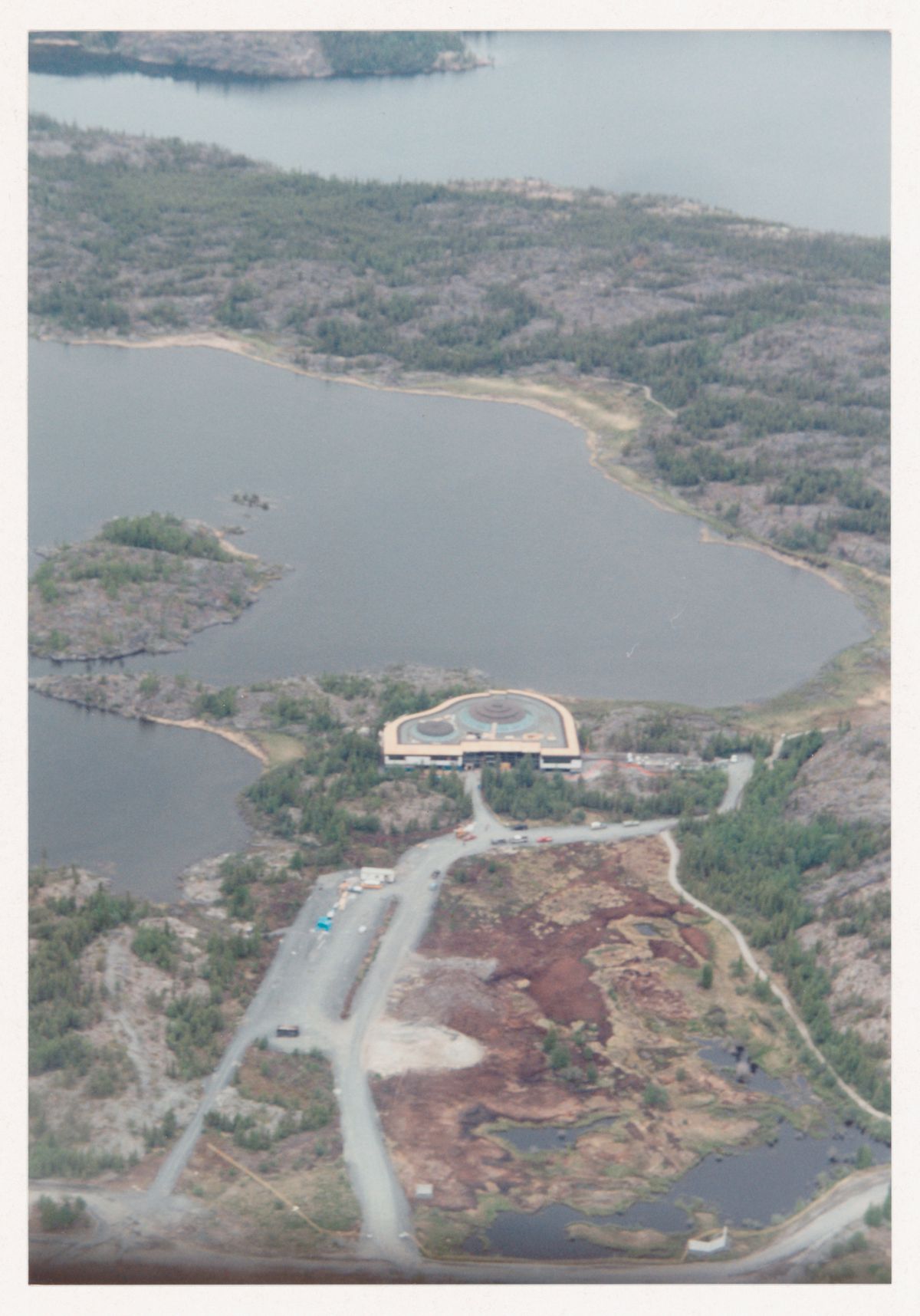

Within the middleground, land is often dispossessed to make way for so-called progress. This case presents controversies surrounding land ownership that coincided with the construction of the New Montréal International Airport (later known as Montréal-Mirabel Airport), designed by Papineau Gérin-Lajoie Le Blanc Architectes (PGL), which opened in October 1975. Montréal-Mirabel was proposed to be the largest airport in the world during a period of urban expansion in Montréal that followed Expo 67 and included the introduction of a new metro system. The new airport required the government’s expropriation of 97,000 acres of land from settler farming families, many of whom continued to protest their displacement for thirty years. Further, unacknowledged in most histories of these events, the land beneath the project remains unceded by the Kanien’kehá:ka of Kanehsatà:ke who have an unresolved demand for legal redress that dates back to at least 1717. In 2006, since much of the land was never used for construction of the airport, the Canadian government sold land back to the expropriés and failed to acknowledge the Kanehsatà:ke’s redress altogether.

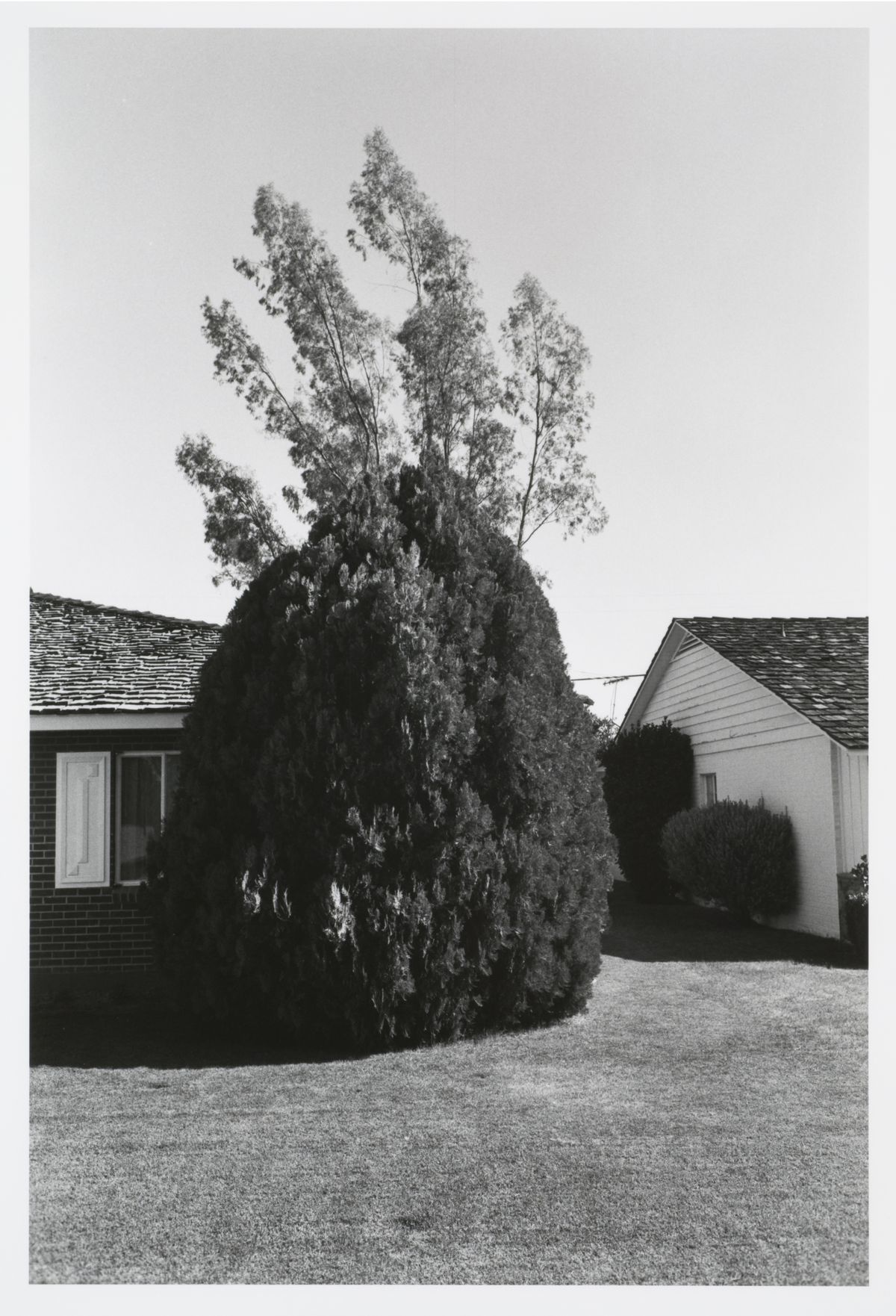

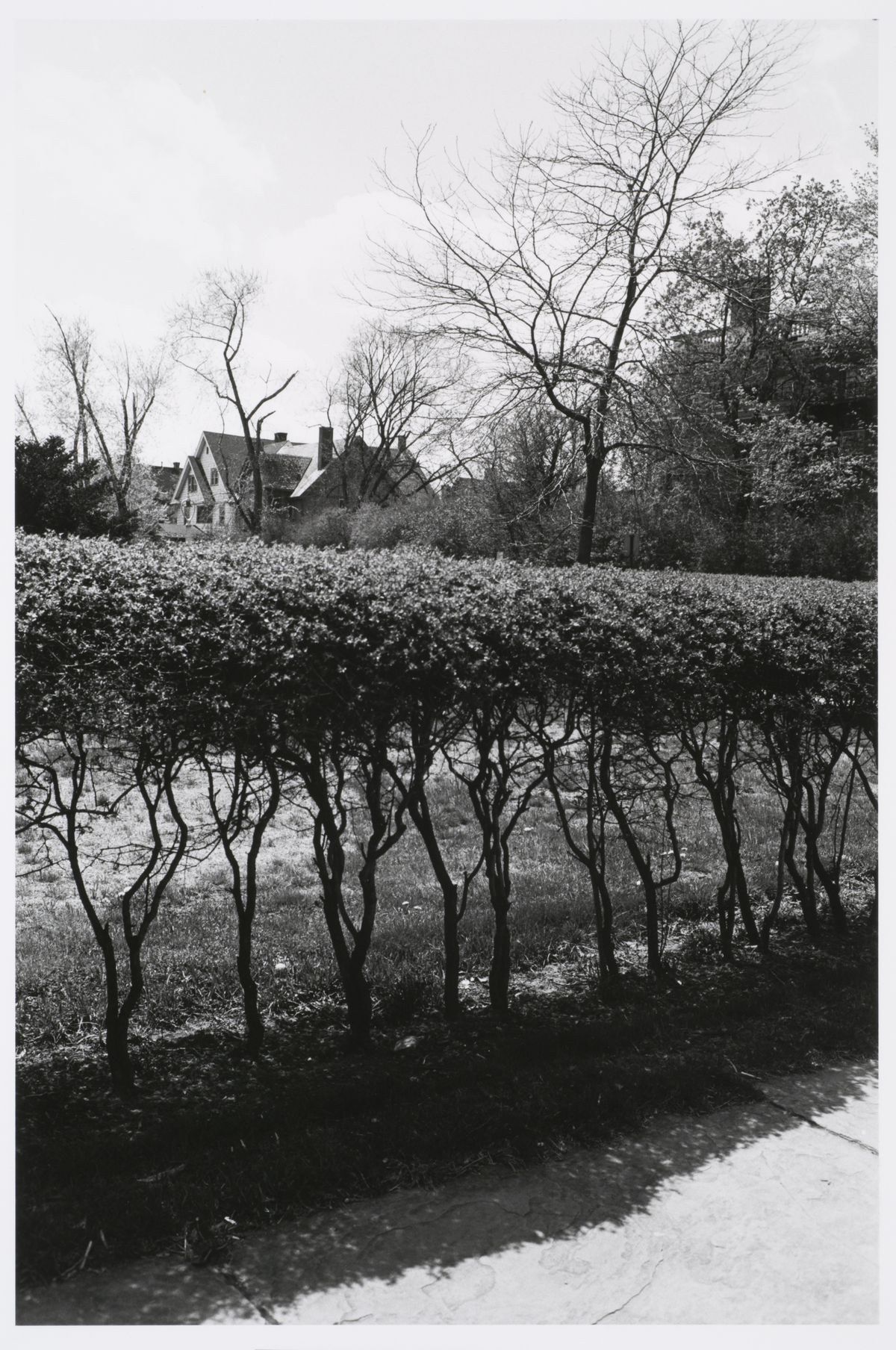

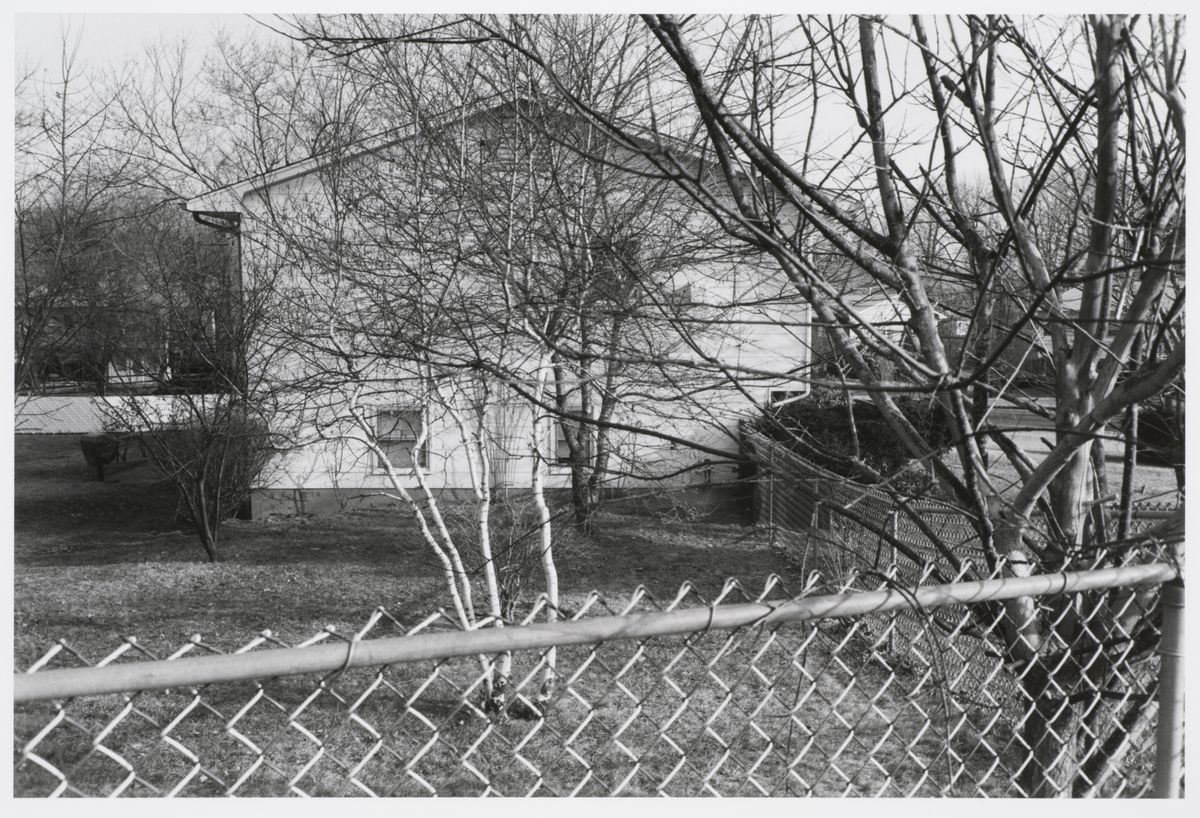

Property allows settlers to benefit from land. After land is captured, its redefinition as property determines a legal right to its possession and use and, in many cases, its development. Suburban landscapes lie between the urban and the rural, marked by deceivingly “natural” interventions such as hedges, trees, and planters that make property lines visible. The creation and demarcation of property thus obscures histories of dispossession and land stewardship under often Indigenous forms of sovereignty and tenure rights.

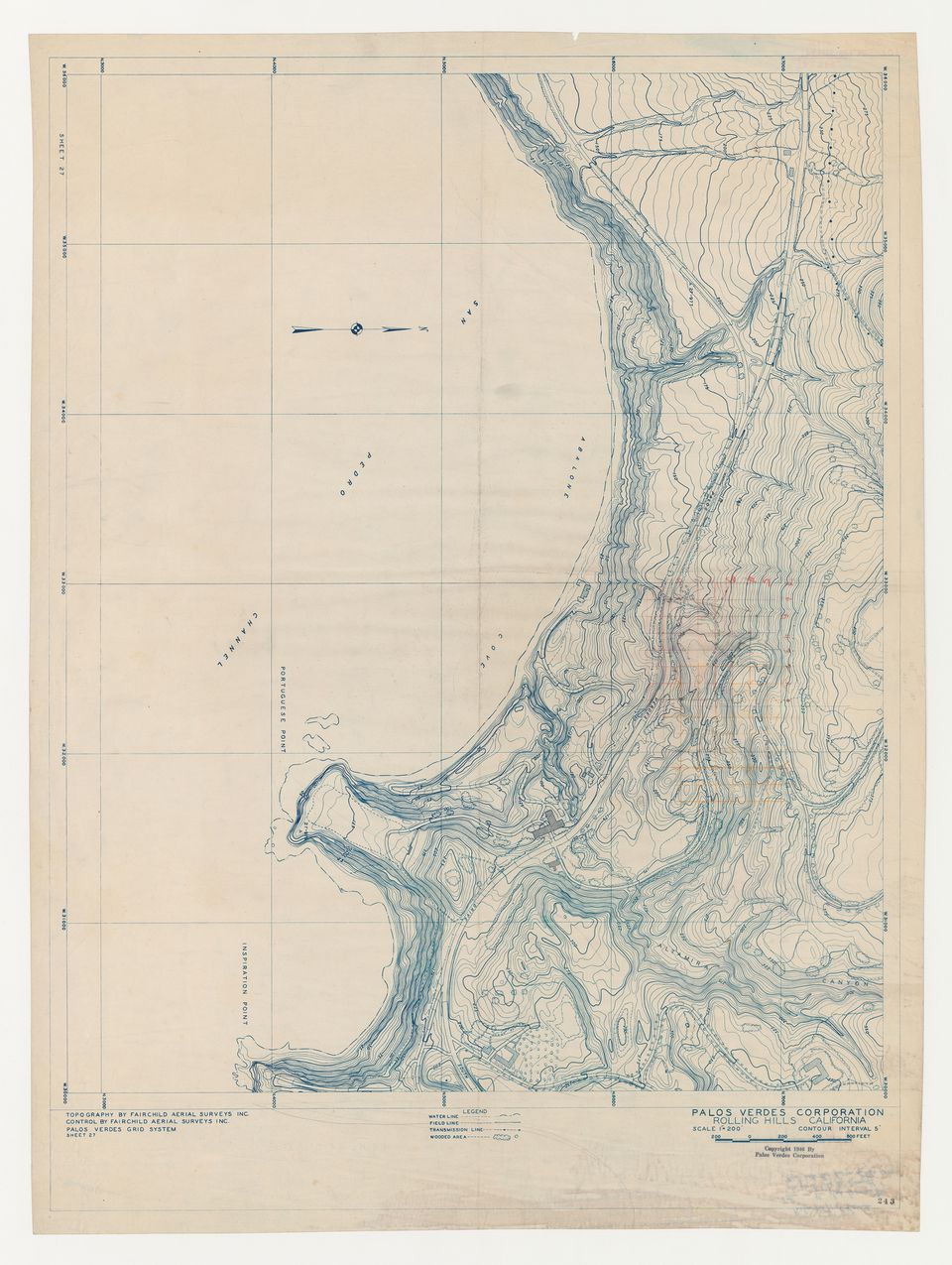

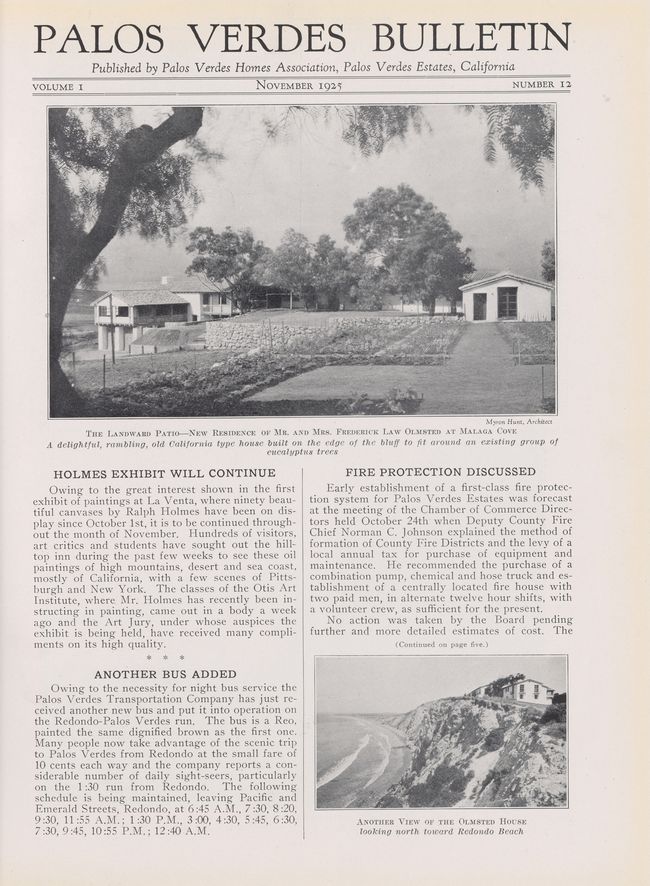

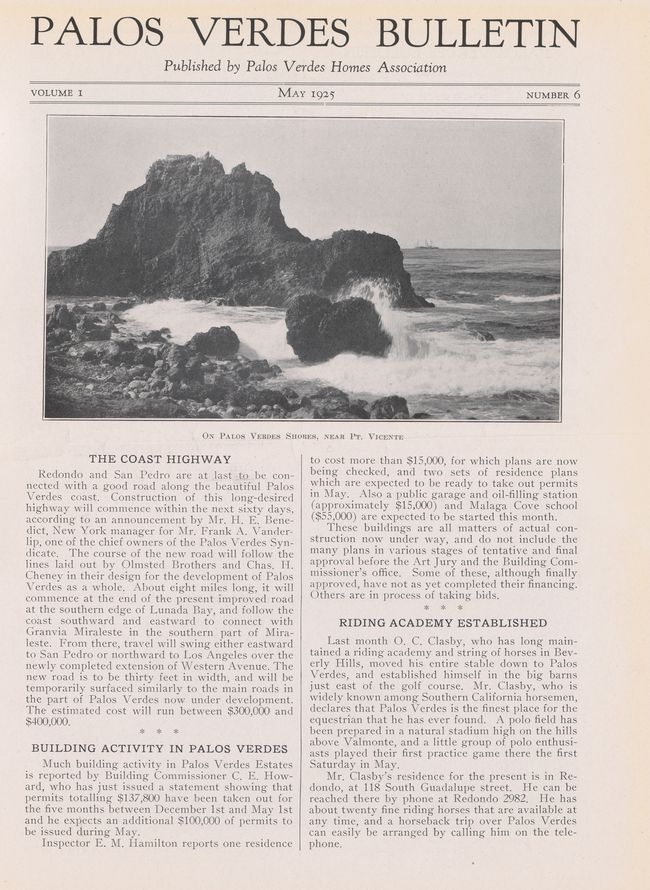

The act of surveying facilitates the assessment of property, creation of territoriality, and control of land through subdivision and construction. Surveys, such as this one of what is now known as the Palos Verdes Peninsula in California, are drawn representations that project the latent possibilities of land ownership. In 1913, the peninsula was purchased by a single property owner, the Palos Verdes Corporation, which entrusted John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to design the development of Palos Verdes Estates. Monthly newsletters, produced by the Palos Verdes Homes Association, show the rapid construction of the new development and forecast a future to homeowners, lot owners, and potential buyers in which land can become property.

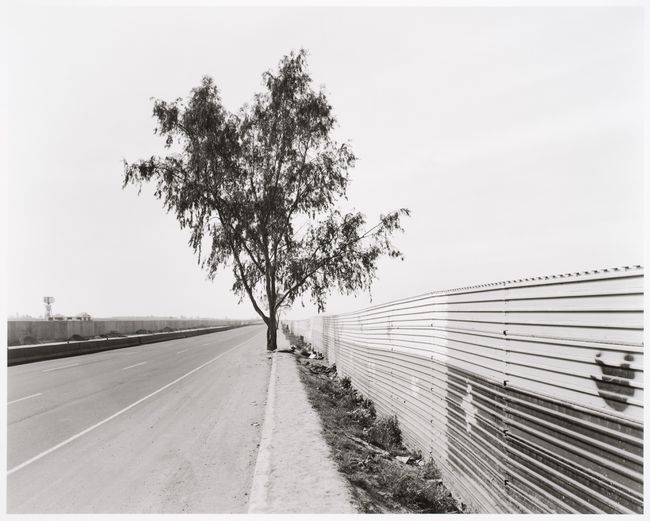

Geoffrey James, view of Kumeyaay Territory, split by the United States-Mexico border fence (Tijuana, Mexico and Cession 310 Territory, San Diego, California), 1997. Gelatin silver print, 46.1 × 57.9 cm. PH1997:0063, CCA Collection, gift of Geoffrey James and Jessica Bradley © Geoffrey James

The ubiquity of infrastructure promotes the idea of shared “common ground,” yet roads that connect are also corridors that divide. The 1984 Louisiana World Exposition spurred the construction of a new monorail and conference centre, two infrastructural interventions that simultaneously separated and restored certain neighbourhoods in New Orleans. Echoes of these projects continue to mark the city’s divided urban fabric to this day.

Walls are understood as necessary for the protection of property; thus they comprise part of the “common ground” of dispossession. This portion of the border wall between the United States and Mexico was built by the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1994. In contrast to the legal inaccessibility it represents, the wall here is discontinuous and climbable—an indication of San Diego and Tijuana’s geographic proximity and the “illegal” crossings that nonetheless take place. The border wall remains an icon of political violence and a reminder of the power that resides in taken-for-granted, omnipresent infrastructure.

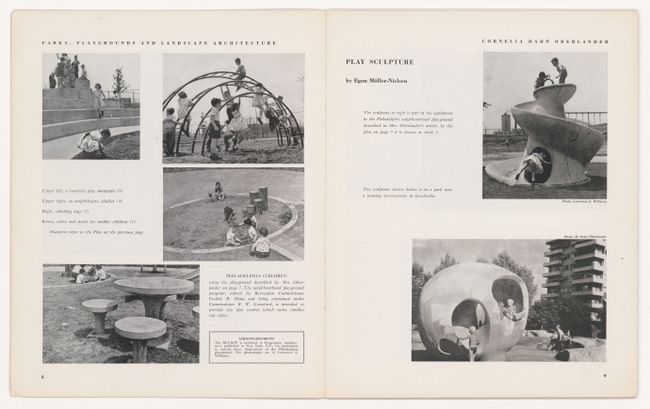

Playground manufacturing company workshop, 18th and Bigler Streets, unceded territory of the Lenni-Lenape people, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), 1954–1956. Gelatin silver print. ARCH284338, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander fonds, CCA Collection, Gift of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander © Cornelia Hahn Oberlander

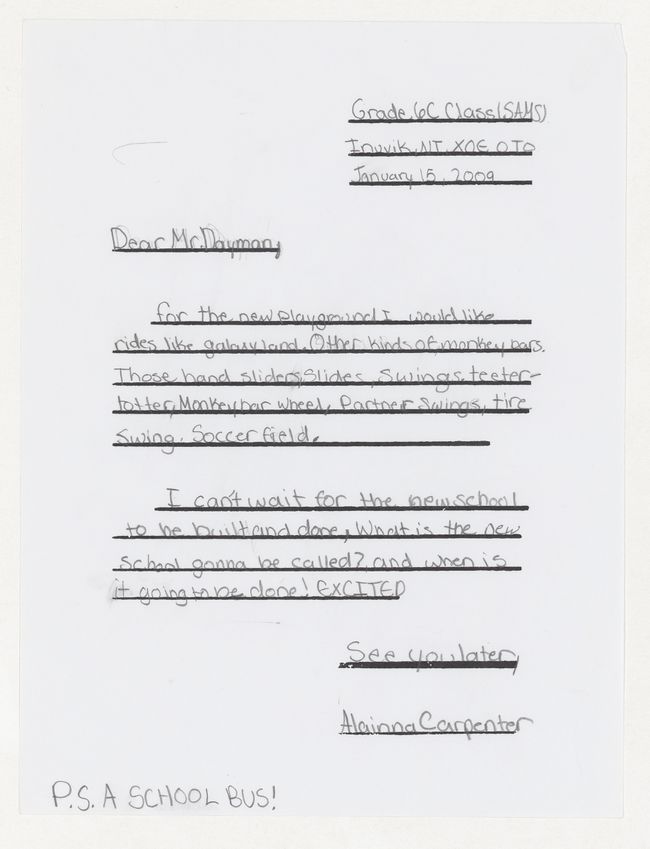

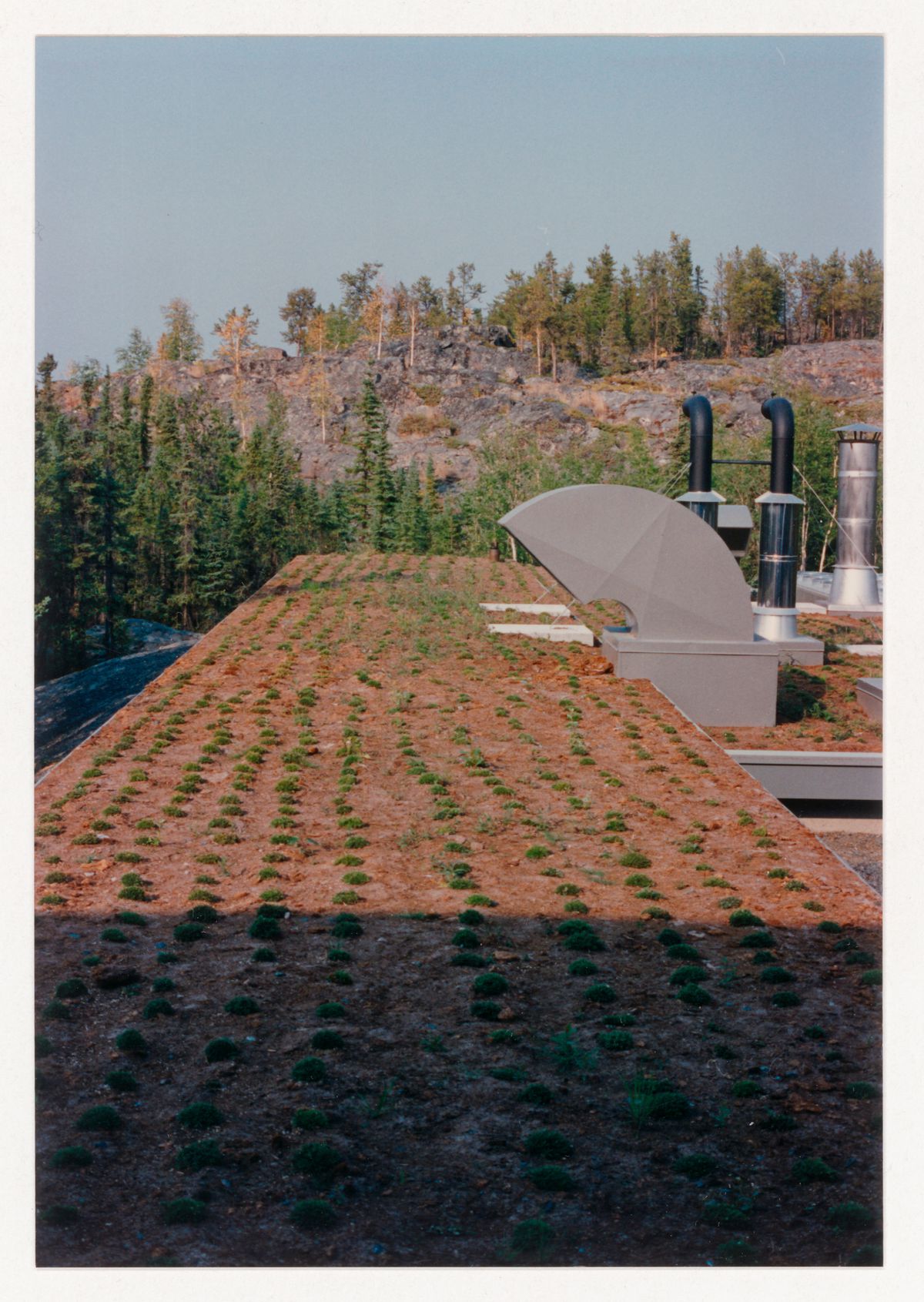

Letter from student for Inuvik School, Inuvik, Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Nunatsiaq, Inuit Nunangat (Northwest Territories), 15 January 2009. Electrostatic print on paper with graphite. ARCH284328, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander fonds, CCA Collection, Gift of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander © Cornelia Hahn Oberlander

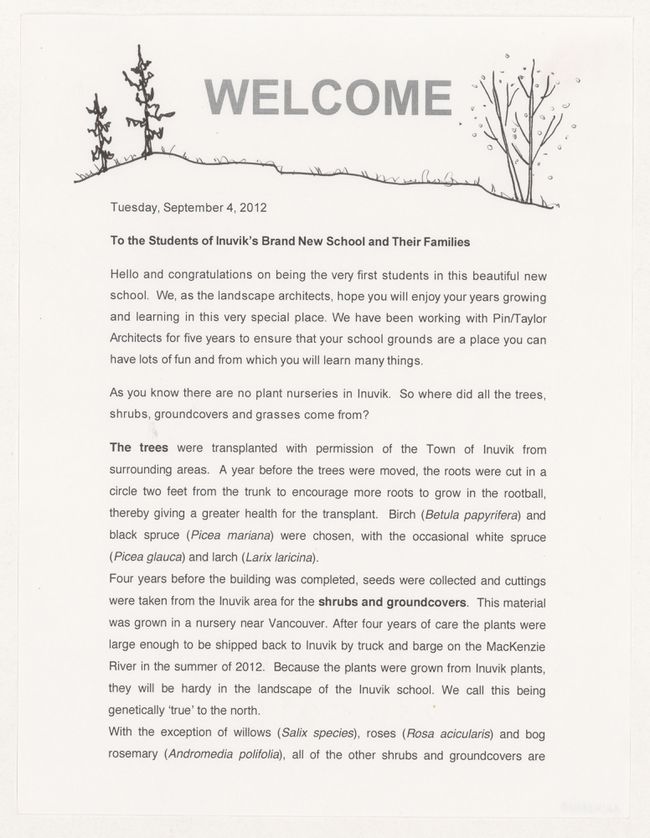

Letter from Cornelia Hahn Oberlander to students and their families, Inuvik School, Inuvik, Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Nunatsiaq, Inuit Nunangat (Northwest Territories), 4 September 2012. Electrostatic print on paper. ARCH283108, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander fonds, CCA Collection, Gift of Cornelia Hahn Oberlander © Cornelia Hahn Oberlander

Since beginning her landscape design practice in 1947, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander has privileged social and ecological responsibility. However, the ways through which she has included local knowledge in the development of projects have expanded. In the 1950s, Oberlander worked for the Department of Recreation and the Public Housing Authority of Philadelphia and enacted a top-down approach for several city playground designs that largely imposed the visions of commissioned artists and designers upon low-income communities. In the 1960s, she designed grading and planting strategies for the Skeena Terrace public housing project in Vancouver, negotiating with municipal officials on behalf of residents to improve the project’s siting. Later in her career, Oberlander’s approach shifted towards a process of working that encompasses more sited and occasionally Indigenous voices, from those of community Elders in what is now known as Yellowknife to those of local students, all of whom could foreground embodied knowledges of their land.

These CCA Collection objects are on display as part of Middleground: Siting Dispossession.