Mikwayndaasowin: Remembering that which was there before

Dani Kastelein questions the boundary between the land and the water

Mechanisms of Canadian government and industry have laboured for centuries to dispossess Indigenous Peoples, affecting First Nations, Métis, and Inuit’s maintenance of traditional land-based practices and spiritual and bodily connections to land and water. Despite colonial processes, Indigenous land defenders and water protectors assert their stewardship responsibilities and rights at various sites,1 reminding us that Indigenous laws existed long before “the rule of law” of Canadian jurisdiction.

For most of the landmass in Canada,2 it was the Royal Proclamation of 1763 that outlined how to “establish” Indigenous land rights and provided a structure for the negotiation of treaties,3 contending that Indigenous land rights were “personal and usufructuary.”4 The term usufruct is defined as “the legal right for using and enjoying the fruits or profits of something belonging to another” rather than a right that is hinged on individual land ownership.5 However, these colonial dissections of land do not reflect the symbiotic relationship between Indigenous Peoples and the landscape. This determination effectively mischaracterizes Indigenous rights and obligations and has worked to dispossess Indigenous Peoples of our lands and narratives. The Royal Proclamation effectively gave the Crown legal jurisdiction to “acquire” the land from First Nation caretakers and remove them from their territories. The transfer of Indigenous lands to the Crown laid the foundation for the application of British law, which Canada adopted, including the concept of “Crown Land” so that the Crown, as an entity, held the “underlying title to all lands in the country.”6 As time went on, additional policies were carefully orchestrated by government as a means not only to continue to facilitate the dispossession of Indigenous lands but to ensure the gradual and total erasure of Indigenous Peoples and our rights. This is especially true in the case of harvesting traditions, including those that exist along the shorelines and on the water.

Under section 35 of the Constitution Act, treaties and harvesting agreements are in place to protect and uphold Indigenous harvesting practices like fishing. Regardless, challenges surface in determining the jurisdiction of the shoreline and access to it. This begs the question: how does one determine the boundary between the land and the water and who is in “possession” of it? The principles in establishing water boundaries derive from the English common law,7 but it is important to note that the jurisdiction of water boundaries vary across provinces and territories. Establishing an absolute demarcation is subjective due to the variability in water levels and the complex observations that must be made of numerous factors such as naturally occurring riprap, vegetation, and other forms of deposition or debris.8

-

Examples include the defence of Wet’suwet’en territory from the Coastal GasLink pipeline in British Columbia, blockades in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en by members of Tyendinaga Mohawk territory, the 1492 Land Back Lane camp in Caledonia Ontario to protect land promised to the Haudenosaunee of Six Nations, and Inuit hunters in Nunavut who gathered to defend their territory from the Mary River Mine expansion in Nunavut. ↩

-

Government officials granted that the provision of terra nullius, a term meaning “nobody’s land” or “no land,” would apply in British Columbia as part of the doctrine of discovery. This denied the existence of any native title. See Blake A. Watson, “The impact of the American Doctrine of Discovery on native land rights in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand,” Seattle UL Rev. 34 (2010): 507, 530. ↩

-

Watson, “The Impact of the American Doctrine of Discovery,” 507, 530. ↩

-

Watson, “The Impact of the American Doctrine of Discovery,” 507, 530. ↩

-

Merriam-Webster, s.v. “usufruct,” accessed November 27, 2020, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/usufruct. ↩

-

Yellowhead Institute, “Land Back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper,” October 2019, 24, https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/red-paper-report-final.pdf. ↩

-

Brian Andrew Ballantyne, Water Boundaries on Canada Lands: That Fuzzy Shadowland (Edmonton, Alberta: Natural Resources Canada- Ressources naturelles Canada, 2016), ix. ↩

-

Ballantyne, Water Boundaries on Canada Lands, vii-viii. ↩

Dr. Brian Ballantyne, in his paper “Water Boundaries on Canada Lands: That Fuzzy Shadowland,” identifies how problematic the action of putting a line on the landscape can be by using the example of two surveyors who were tasked with identifying “The High-Water Mark” along a lake in the Northwest Territories. Adapted from figure #14 “Two surveyors’ opinions of a water boundary, NWT” in “Water Boundaries on Canada Lands: That Fuzzy Shadowland” by Dr. Brian Ballantyne, 2016, Natural Resources Canada-Ressources naturelles Canada.

The process of establishing a water boundary is made even more difficult in places where tidal-like changes occur. Theses areas, found throughout the Great Lakes, have been designated by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) as “dynamic beach environments” and defined as sensitive sites requiring environmental protection.1 The intent of this classification was made to preserve the shoreline and the dunes from erosion, and to protect sensitive habitats of various bird and plant species. These dynamic beach environments are prevalent in Georgian Bay along the shorelines of Tiny Township, a peninsula on the Bay’s southeastern edge.2

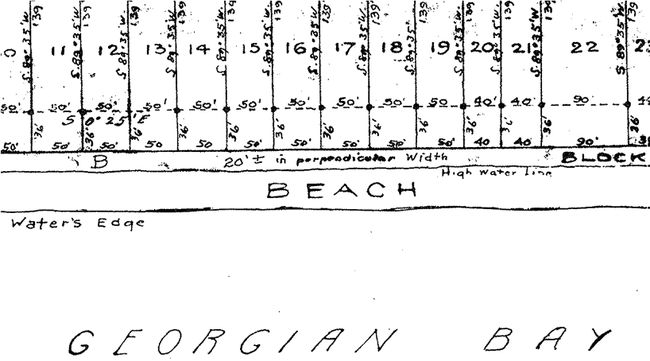

The water boundary in many parts of Ontario, including that of Tiny Township, was historically determined by what the government had identified as the High-Water Mark (the highest point where the water’s edge can climb up the shoreline), not to be confused with the water’s edge. The intention was not only to consider the variable changes in water level but also the provision of shoreline access for boats to land and launch from during the commercial logging and fishing boom of the late nineteenth century. The Crown’s surveyors were responsible for mapping out the municipal shore allowances, including a sixty-six-foot strip of land along the shorelines of Georgian Bay. Recently, however, a new provision was made for shoreline setbacks in Georgian Bay to comply to a 178-metre elevation. These changes in the setbacks were made not only due to the variability of the High-Water Mark but also subsequently due to the subjectivity in identifying that boundary.

While these changes were made in the hopes to clarify the jurisdiction of the water boundary, the title of shoreline ownership in the area is still quite varied. Some property owners have purchased the land “to the water” and subsequently have riparian rights, while others may not. Unfortunately, there is still confusion regarding the extent of someone’s land title due to the tidal-like changes of the water as well as the rights regarding the use of the beach and ability to build along the shoreline. Tiny Township has, therefore, become notoriously strife with tensions between public policy and private beach rights.1 For years there have been disputes regarding public access to the beaches, which has produced a division between beachfront owners who want to create a private beachfront and the public (including “backlot” owners) who have been accessing the beaches for generations. Private beachfront owners have gone as far as erecting fences, barricades, and even rock walls in the hopes of preventing people from walking the beach or swimming, spurring many confrontations between beachfront owners and the public.

-

Andrew Mendler, “Hot spots for conflict: Tiny Township to assess waterfront property boundaries,” The Peterborough Examiner, May 7, 2021, https://www.thepeterboroughexaminer.com/local-midland/news/2021/05/07/hot-spots-for-conflict-tiny-township-to-assess-waterfront-property-boundaries.html. ↩

A sign that reads “Private beach to water’s edge. No Trespassing,” Balm Beach in Tiny Township, ON. In Dani Kastelein, We Belong With the Water: Mobility, temporal habitation, rituals, and other ‘incidental’ elements surrounding fish harvesting traditions of Indigenous communities in Southern Georgian Bay - A Graphic Novel, (Waterloo, Ontario: UWSpace, 2020), 271

Amidst these jurisdictional conflicts, the rights and existence of Indigenous populations along the shoreline have been overlooked. Long before these waterfront properties existed, the beaches were used as sites of temporary habitation and of harvest. However, the practice of building transitory cabins and docks along the shorelines throughout the Great Lakes no longer endures. The answer as to why is linked to a long and complex history that I will attempt to summarize. During the commercial fishing boom in the late nineteenth century, Indigenous Peoples encountered pressure, violence, and racism from settler fishers who drove them out of their traditional harvesting grounds.1 Later, sport fishers and the discipline of western fisheries science used their position and authority to restrict Indigenous fishing systems under the guise of resource management and conservation.2 Subsequently, socioeconomic and cultural shifts following the Second World War allowed leisure activities to become more common among the middle class, making beaches and shoreline property more desirable. As the beaches became more popular and, therefore, more populated over time, the effects on the use of the shoreline for harvesting were devastating. The delineation of the land through the process of identifying areas of environmental concern, leisure, and private ownership also created an opportunity for the government to develop polices to support activities within those classifications and prohibit those incidental to harvesting. This led to establishing laws, including in Tiny Township, prohibiting anyone from disturbing these spaces save for “passive enjoyment,” ensuring they be “maintained as close as possible to a natural state.”3

Although section 35 of the Constitution Act protects Indigenous Peoples’ ability to carry on activities that are integral to our Nations, these rights are not clearly defined. This has resulted in constitutional challenges as to what is integral to certain practices including landscape modification, access, and use of natural resources. For example, in accordance with the Sparrow test,4 treaty rights can be infringed upon by provincial legislations necessary for conservation, including those that restrict building anything that could be construed as a permanent structure.5 While incremental changes have resulted in “recognized” rights that have restored some power over lands and resources for Indigenous communities, through landmark cases such as the Marshall decision, Powley, and Sundown, they do not always protect Indigenous Peoples from violence rooted in misbelief, racism, and indifference.6 Moreover, the restrictive process of “negotiating” for Indigenous rights in court is anything but equitable. The goal of these negotiations has always been predicated on “limiting Indigenous rights within federally managed discussions from which solutions are predetermined by federal policy.”7 Due to the established legal precedent of “Crown Lands,” even if a First Nation establishes that their territories were and are unceded, there is still no way to resume full jurisdiction and governance authority through legal means.

When evaluating strategies to reinstate Indigenous presence on the land and along the water, some argue that it is critical to de-centre oneself from the legal framework established by the federal government. Re-occupying land previously occupied and/or physically resisting dispossession is one strategy that can be used to assert Indigenous jurisdiction and actively resist settler authority. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson argues that the key to Indigenous resurgence is tied to the notion of “grounded normativity”8 or a reattachment of our minds, bodies, and spirits to form non-hierarchical relationships with the land.9 She argues that harvesting medicines and food must be practiced, unapologetically, in whatever capacity within our altered landscapes, whether that be in an urban, suburban, or rural environment. Simpson provides examples through her storytelling in short stories such as “Plight” and “Circles Upon Circles,” which follow her protagonists reviving the practice of harvesting wild rice in cottage country or tapping maple trees in a Toronto park.10 These stories mirror the changes evidenced in communities such as Pigeon Lake First Nation, where activities like the yearly ritual of wild rice harvesting have been renewed.11

-

Edwin C. Koenig, “Native fishing conflicts on the Saugeen-Bruce Peninsula: perspectives on resource relations past and present,” (PhD diss., 2000) p. 86, 106, 115. ↩

-

Michael J. Thoms, “Ojibwa Fishing Grounds: A history of Ontario fisheries law, science, and the sportsmen’s challenge to Aboriginal treaty rights, 1650-1900.” (PhD diss., University of British Columbia, 2004), 2-6. ↩

-

Township of Georgian Bluffs, “Policy Use of Unopened Road Allowances,” March 24, 2010, 3, https://www.georgianbluffs.ca/en/resourcesGeneral/PDFs/Policies/TRA-010-10_Use_of_Unopened_Road_Allowances_0.pdf. ↩

-

The Sparrow test is used to interpret section 35 of the constitution when determining if a government activity threatens to infringe on an Indigenous right. There are two parts for the test. Firstly, it asks; “has a right been infringed on?,” this includes imposing “undue hardship” and denying the “preferred means of exercising that right.” The second part of the test outlines the reasons for which that right may be infringed on, which includes if it serves a “valid legislative objective, such as conserving and managing a natural resource.” See Gérald A., “Sparrow Case,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, ed. Michelle Filice, February 7, 2006, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sparrow-case. ↩

-

Kent McNeil, “Treaty Rights, the Indian Act, and the Canadian Constitution: The Supreme Court’s 1999 Decisions,” Canada Watch 8, no. 1-3 (2000), 45. ↩

-

Steve McKinley and Alex McKeen, “‘The RCMP just stood there’: Attack on Mi’kmaq fishery sparks tense standoff, condemnation,” Toronto Star, October 14, 2020, https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/10/14/mikmaq-chief-slams-nova-scotia-fishery-violence-they-are-getting-away-with-these-terrorist-hate-crime-acts.html. ↩

-

Rolland Pangowish, “The Last Word: Statement by Long-Time Odawa Policy Analyst Rolland Pangowish, on AFN and Chiefs’ ‘Negotiations’ within Canada,” First Nations Strategic Bulletin 18, no. 6-12 (June-December 2020), 24, https://mediacoop.ca/sites/mediacoop.ca/files2/mc/fnsb_june_dec_20.pdf. ↩

-

Dene political theorist Glen Coulthard defines the notion of grounded normativity as Indigenous land-connected practices and associated experiential knowledge that “inform and structure our ethical engagements with the world and our relationships with human and nonhuman others over time.” See Glen Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2014). ↩

-

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance (University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 44. ↩

-

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, This Accident of Being Lost: Songs and stories (Toronto: House of Anansi, 2017), 5-8, 75-78. ↩

-

Rhiannon Johnson, “Cottage Country Conflict over Wild Rice Leads to Years of Rising Tensions,” CBC News, November 12, 2018, https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/kawartha-lakes-pigeon-lake-wild-rice-dispute-1.4894495. ↩

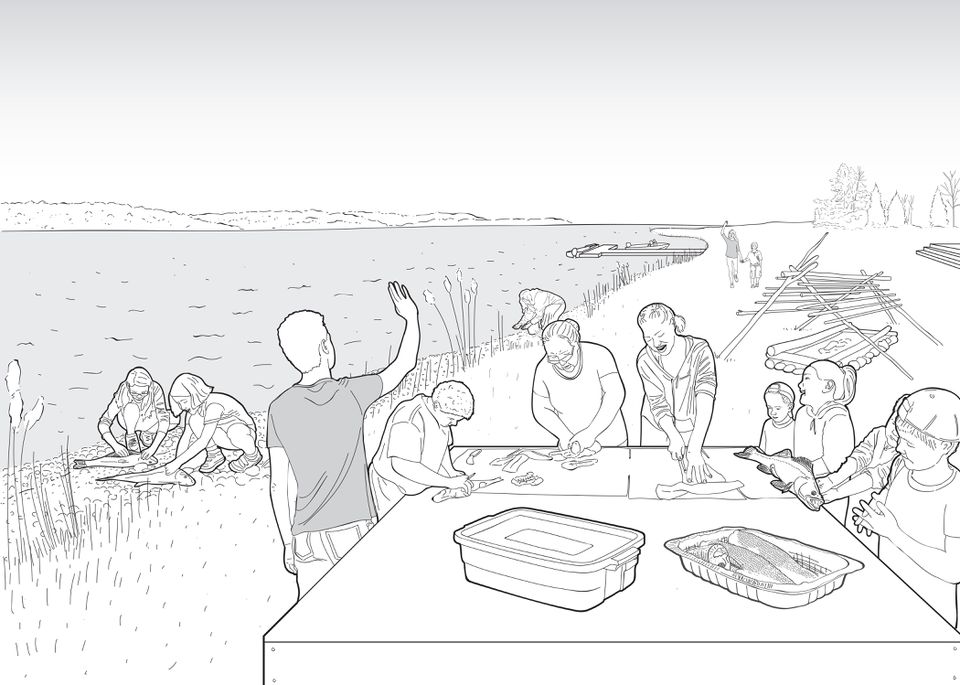

In reinvigorating Indigenous harvesting practices, the process of grounded normativity could be supported and anchored by Indigenous tectonics. Docks, cabins, and other constructions can serve as tangible tools to confront the hegemonic paradigm between public and private space, ownership, and rights, one which reinstates Indigenous presence on the land and the water. At the core, Indigenous harvesting rights, water access, and temporal structures linked to the practice are pieces of a larger story. They represent the ability for self-determination and mobility. The making of incidental elements such as drying racks, which include pole harvesting and rope fibre production to latch them together, provide a means of transmitting teachings that link us both to culture and to the land. These tools are not meant to only exist in our past, nor are they intended to remain static, but rather to continue to inform our ethical engagement with the land. It is our disenfranchisement that helped fuel a fundamental misunderstanding that these tools and techniques were never intended to lead us forward. Reappropriating this knowledge will work to make our rights, systems, and laws visible, thereby challenging those linked to settler colonialism, including “the colonial dissections of our territories.”1

Throughout her work, Simpson contends that government policies and entities, such as the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, have “no real physical power over us.”2 In determining the path forward, she suggests that “If we accept colonial permanence, then our rebellion can only take place within settler colonial thought and reality.”3 This reality continues to have a negative effect on our psyche. For decades it has taken away our confidence in articulating our rights and respecting our laws for fear of encountering resistance not only from government bodies but from interjecting colonialist thoughts, Western perspectives, and, as we have seen, violence from settlers. The challenges that Indigenous Peoples face in re-establishing a relationship with the land and our relations are beyond those that dispossess our bodies of the land, for they are tied to the deep psychological and spiritual traumas of colonialism.4 In the process of resurgence, it is critical for the continuance of Indigenous Peoples and knowledge to consider, as Isaac Murdock (Bombgiizhik)5 points out, that the land and its spirits do not recognize status cards; that all you need to connect to ceremony, medicines, and the land is to go out and reclaim it.6

-

Simpson, As We Have Always Done, 173. ↩

-

Paula Sherman, “Chapter 6, The Friendship Wampum: Maintaining Traditional Practices in Our Contemporary Interactions in the Valley of the Kiji Sibi,” in Lighting the Eighth Fire: The Liberation, Resurgence, and Protection of Indigenous Nations, ed. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring Publishing, 2008), 121-122. ↩

-

Simpson, As We Have Always Done, 153. ↩

-

Simpson, As We Have Always Done, 153. ↩

-

Isaac Murdoch, whose Ojibway name is Manzinapkinegego’anaabe / Bombgiizhik (fish clan from Serpent River First Nation) is an artist, activist, and environmentalist. ↩

-

Isaac (Bomgiizhik) Murdoch, “Indian Act Bunk….” Facebook, December 9 2020, https://www.facebook.com/100008333559927/videos/2801482196806205. ↩

Dani Kastelein wrote this text as an extension of our exhibition Middleground: Siting Dispossession, on display until February 2022.