Caption This

Shukri Sultan and Endriana Audisho, Julia Ramos, and Jacqueline Tran on the stories constructed by the collection, documentation, cataloguing, and sharing of photography

This is the second article in a series that reflects on the value of interpretation in combination with the technical practice of cataloguing, authored by CCA staff and invited scholars and introduced by Martien de Vletter. Here, we examine the construction of narratives through photography. CCA curatorial intern (2022-23) Shukri Sultan uncovers the complex histories of a building hidden in the catalogue entry of a photograph within the CCA collection, and Endriana Audisho, Julia Ramos, and Jacqueline Tran examine counter-narratives developed through the dissemination of photographs on social media.

Beyond a caption

Shukri Sultan considers what remains to be unearthed

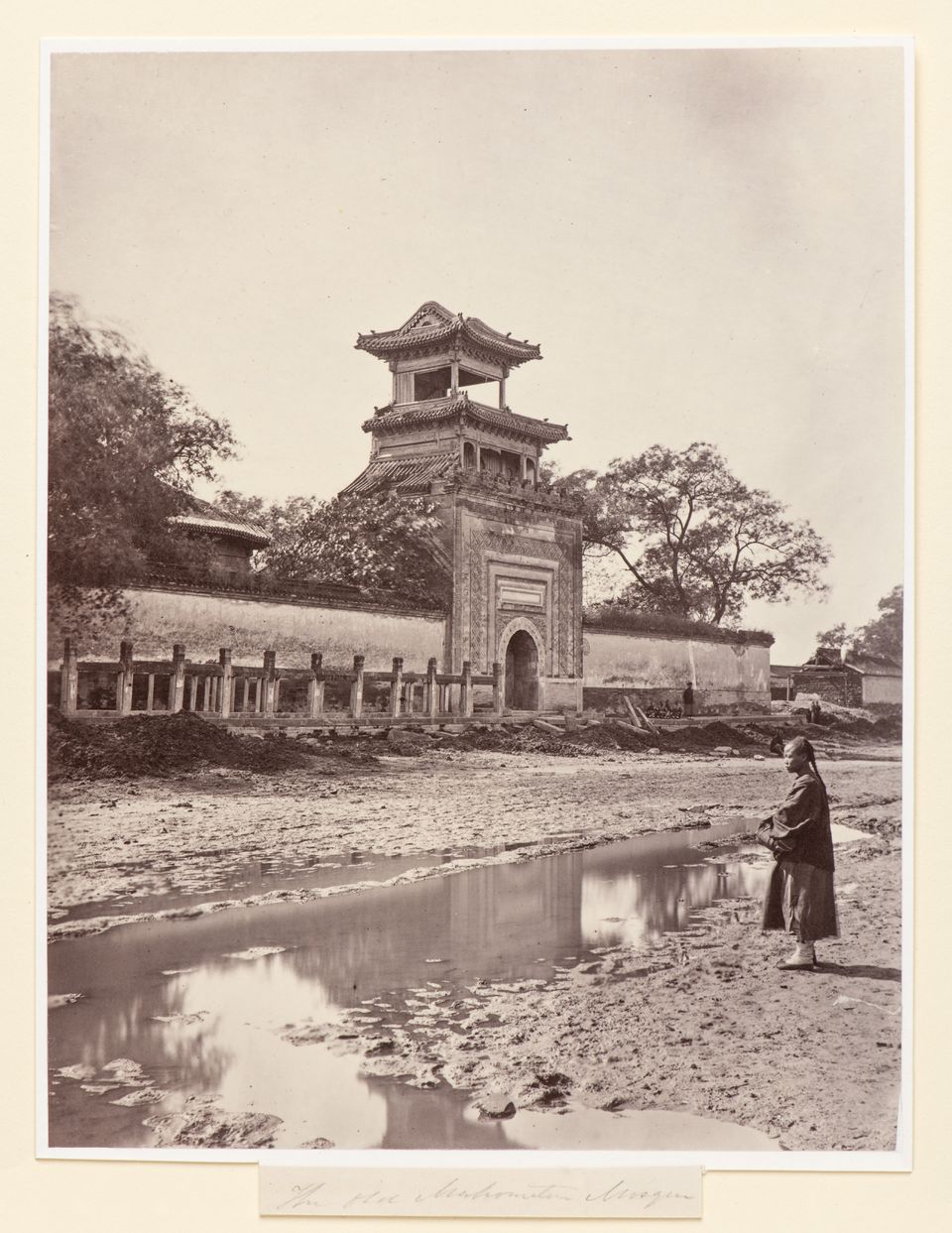

The direction of prayer for all Muslims—whether in a repurposed gym in Utqiagvik, Alaska or in an open-air Bedouin mosque in eastern Jordan—is the Ka’bah in the city of Makkah. Yet, evident in the image above of a mosque in Peking (now Beijing), this imperative rule was disobeyed. An adorned arched doorway topped with an elaborate banggelou (minaret), centres the photograph, taken by the Scottish geographer John Thomson in 1871.1 In the foreground of the photograph, stands an unnamed figure, whose role and relationship to the building are unknown. Beyond them, barely discernible, are four people sitting outside of the mosque compound wall; beside them stands a man in a turban, and further to his right are two blurry figures. Too small to be purposefully staged, these minor figures appear to be locals. Beneath the relatively benign scene presented here, lays a harsher truth. The supposed mosque at the centre of this photograph did not face Makkah but rather instead was designed and built to face the emperor’s throne. However, none of this was apparent to me when I first came across this image, in the CCA photography collection, rather, this narrative was concealed by the insufficient constructed title ascribed to it.

I stumbled upon this image, as part of an object package list that I reviewed for the Critical Cataloguing project. It was then accompanied by the title—View of the main gateway to a mosque, Peking (now Beijing), China. I decided to probe beyond the caption in a bid to perhaps identify the building or learn more about its architectural details. Subsequently, what we—the Critical Cataloguing team—uncovered revealed a narrative saturated with questions of identity and power. A narrative that depending on the narrator is embellished with romance or subsumed by genocide. This photograph and the contested history attached to it, encapsulates Edward Said’s statement that “nations are themselves narrations.”2 And although this narrative was crafted by a Manchurian Emperor, the ongoing settler-colonial project and current genocide of Uyghur people by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in pursuit of assimilating them into Han culture is tied to this mosque, as it can be argued that it was Qing imperial ideology that laid the foundation for a “multi-ethnic China.” In reviewing this photograph and its hidden narratives, our challenge was to consider, how this complex history can be reflected in the catalogue entry of the object.

The mosque in the photograph is located just outside of the Imperial City in Beijing and was constructed under the order of the Qianlong Emperor (1736 - 95), allegedly to console and woo Xian Fei, his “Fragrant Concubine” a Turkic-Muslim woman, taken from the recently annexed Altishahr (today’s Xinjiang).3 This legendary, allegorical figure, who refused the advances of the emperor, symbolized the forcible integration of the Turki people (today’s Uyghurs) into the Qing Empire.4 This symbolic union was commemorated in stone by combining Manchurian construction techniques and central-Asian decorative motifs. This was the only mosque to have been built using the Court treasury throughout the Qing dynasty, but it was neither its unique patron nor its mishmash style that separated it from the other mosques of Beijing. Instead, it was the orientation of the prayer hall that made it distinct. The local, Beijinger Muslims,—who have been present in the city since at least Tang dynasty (618 -907)—conscious of their peripheral position and distance from the sacred city of Makkah, orientated not only the prayer hall but all ancillary buildings within a mosque complex towards the holy city.5 Uniquely, as stated earlier, this mosque did not face Makkah but instead faced the emperor’s throne.6

The photograph’s original caption not only failed to convey this complex narrative but, through its insufficiency, concealed this history. We, the Critical Cataloguing team, set to rectify this. Through research and countless debates over semantics, we agreed on the current revised (or reconstructed) caption—View of the entrance to the Huiziying Qingzhensi (mosque of the Turkic-Muslim Camp, now demolished), Peking (now Beijing), China. This process revealed to us, that no caption can ever be absolute, and the process of critical cataloguing is indefinite. In a bid to be concise, silences and gaps formed, and this current caption still harbours questions regarding names and shifting identities. Huiziying Qingzhensi, the name that has been ascribed to this building by historians, is far from exact and encompassing.7 Deriving from the area, it can be translated as the “Hui camp.”8 The label Hui historically has had multiple uses. It was firstly used as a general term to refer to Muslims, Christians, and Jewish travellers from Western Asia.9 Towards the latter half of the nineteenth century, the term came to solely refer to Muslims, with Islam being known as Huijiao, (the religion of the Hui) and it followers as Huijaotu.10 With the advent of Social Darwinism in the same period and the introduction of Japanese racial terminology, minzu, the term Hui then emerged as its own ethnoreligious group, ascribed to Sinophone Muslims.11 However, this mosque was built for a different ethnic group, a Turkic-Muslim community, who, prior to the construction of this mosque, had been forcibly converted into imperial subjects. The name of the area and subsequently the mosque comes from an era when the label Hui referred to all Muslims, despite the term now being used solely to refer to Sinophone Muslims.

The main predicament when captioning this photograph is whether we can refer to the building it depicts as a qingzhensi (a mosque) or not. Personally, as a Muslim myself, I find it inconceivable to consider this building a qingzhensi, it is more akin to an architectural folly, and I can assume the Muslims of Beijing would have also struggled to come to terms with it. From an Islamic jurisprudence perspective, a mosque is a place that has been permanently set aside for the five daily prayers to be performed in, often through a waqf (an endowment that renders the property no longer under the ownership of the owner, in this case the emperor). The primary function of a mosque is to provide space for Muslims to congregate and worship collectively. There are minor variations in the way Muslims—despite differences in sects or schools of thoughts—perform the ritual prayer. Each prayer starts the same, the first bodily act is to orientate our body to face the qiblah. This act goes beyond just physically orientating, through this movement we are refining and attuning ourselves to the presence of God, so that we may be able to perceive Him wherever we may be. What then of this mosque that goes against this imperative and defining act? Out of the three most common and basic components of a traditional mosque, mihrab (niche in the wall indicating direction of Makkah), mimbar (pulpit) and minaret, I would argue that the mihrab is the most important. Even in the humblest of mosques there is some ad-hoc sign in lieu of the mihrab, attesting to the importance of the direction of prayer.

Built a decade after the annexation of Altishahr, which saw the complete annihilation of the Dzungar people, this qingzhensi was constructed as a form of humiliation and patronage of Turkic-Muslim people.12 Here, the emperor has commemorated the subjugation of the Turkic-Muslims by building them a place of worship that defies the basic principles of their faith and inserting himself in their daily prayers.13 Rather than viewing this building as a place of religious worship it can be read within a wider landscape of war commemorations commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor. The stela, which once sat in the qingzhensi compound, displays a text written by the emperor inscribed in four languages: Manchu, Chinese, Mongol and Turki (also known as Chagatai written in a Perso-Arabic script). The multiple languages were a reiteration of the Qing imperial quest to redefine China and what constitutes a Chinese language.14 The text exaggerated the importance of the qingzhensi as it proclaimed the wonderment of visitors and falsely stated that it was the first mosque to be built in China, despite the steady presence of Muslims from at least the Tang dynasty (618 -907).15 The only unprecedented aspect of the Huiziying Qingzhensi is the direction of prayer that it mandates.16

Despite the genocidal history behind the inception of this building there is evidence that this qingzhensi was cherished and used as a place of worship by some. When the qingzhensi was demolished at the order of Yuan Shikai (first President of the Republic of China, 1912-16), Ma Rong’en, who was then the Akhun (religious leader), attempted to rebuild it, but it remained incomplete at his death in 1937.17 In spite of the inception of the building, if the community regarded and used it as a qingzhensi then can it indeed be perceived it as one?18 However, it is only the voices of the male leaders of the community—those “endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor”19—that are presented in the writings of historians.20 How can we then give agency to the marginal accidental figures in the photograph (and others like them)? While the emperor’s inscription suggests that the qingzhensi was not opened to public, it is possible that those accidental figures may have appropriated the space, ignored the false qiblah and prayed facing west, towards Makkah.21

In revising this caption, I attempted the impossible task, “to reconstruct the past is, as well, an attempt to describe obliquely the forms of violence licensed in the present.”22 The fate of the marginal figures may remain unknown but their descendants alongside vestiges of the building continued to be present on the site until 2008 when the area was redeveloped by the city government. No longer registered as Turkic and they were regarded as Huizu, Sino-Muslims.23 However the violent Sinification of this community was completed, long before 2008. When the missionary Marshall Broomhall visited in 1910, he noted that only the older members of the community could still speak Turki and that of the younger generation, “all their customs and dress, except for religious matter are purely Chinese.”24 Thus the Qianlong Emperor’s project of assimilating the Turkic-Muslim—of this neighbourhood at least—was completed in just over a century. However, the quest to fully integrate Xinjiang into the Chinese nation is an ongoing process which continues today.

Photography and language are central to how the contemporary project of the CCP is disseminated to the public. In the past decade, the plight of Uyghurs has gained wider attention due to open-source research and leaked reports which reveal an apparatus of terror—composed of internment camps, residential schools, sterilization, and forced labour—devised to eradicate the Uyghur identity and culture.25 26 And like the false qiblah of the Huiziying Qingzhensi, this battle is being spatially fought through architectural styles of mosques, and the proliferation of surveillance technology in cities. In contrast, Sino-Muslims in China enjoy greater religious freedom, with moments of leniency, such as the early 2000s; which saw an increase of Hajj attendance—albeit under stringent conditions.27 However, they have begun to feel the brunt of the CCP quest to produce a “Sinicized” version of Islam.28 This contradicting treatment of Muslims minorities by the CCP mimics the narrative of favoured “Fragrant Concubine” and it is indicative of how “Uyghurs have become racially Muslim in ways that the Sinophone Hui have not.”29

Past and present inform each other. Historical objects cannot be quarantined to the past; how we read this photograph, of a mosque constructed in 1760s Beijing, informs our understanding of the current genocide of Uyghurs in China today. In turn the current genocide informs our reading of this photograph—no longer do we just see a slightly dilapidated qingzhensi, but also an embodiment of terror. And amidst the obfuscation of truth, this caption, the words ascribed to this photograph, plays a part in the ongoing battle of narratives.

-

Thomson took this photograph on his second expedition to Asia in 1871, over a century after the building’s construction, hence the subsequent disrepair and deterioration. ↩

-

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism, (London: Vintage Random House, 1994), xiii. ↩

-

The Tarim-Basin part of today’s Xinjiang, has historically been referred to as Altishahr, which although may not appear on any map it is a term that persists in everyday speech amongst Uyghurs, see Rian Thum, The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014), 3. ↩

-

There are historical records of a Turkic women who entered the Qing Imperial Haram in 1760s. However, her name and narrative are disputed and has been embellished and romanticized in Chinese popular culture. See James A Millward, “A Uyghur Muslim in Qianlong’s Court: The Meaning of the Fragrant Concubine,” The Journal of Asian Studies 53, no. 2 (1994): 427–58, https://doi.org/10.2307/2059841. ↩

-

Not all mosques are built facing Makkah, especially if situated in repurposed buildings, however internally the prayer hall is orientated facing it and the direction of Makkah is usually indicated by the mihrab (a niche in the wall). For example, the recent Cambridge Central Mosque designed by Marks Barfield Architects in UK. ↩

-

This is evident in number of written sources, see Tristan G. Brown, “Towards an Understanding of Qianlong’s Conception of Islam: A Study of the Dedication Inscriptions of the Fragrant Concubine’s Mosque in the Imperial Capital”, Journal of Chinese Studies no. 53, (July 2011): 143. ↩

-

Brown, 138. ↩

-

Since the Tang dynasty and till this day, there have been various Muslim enclaves in Beijing, some also referred to as Huiziying often peripheral to the city. See Wenfei Wang, Shangyi Zhou, C. Cindy Fan, Growth and Decline of Muslim Hui Enclaves in Beijing”, Eurasian Geography and Economics, (2002), https://doi.org/10.1080/10889388.2002.10641195. ↩

-

Similarly the word “Qingzhensi” was used to refer to Synagogues as well, see Marshall Broomhall, “Islam in China: A Neglected Problem”, China Inland Mission, (1910): 176-177, https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_ObcNAAAAIAAJ/mode/2up. ↩

-

Kelly A. Hammond, China’s Muslims & Japan’s Empire, (The University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 9. ↩

-

The word minzu has multiple meanings, such as nationality, peoples etc. There is a total of 56 recognised minzu in China, 10 of which as Muslim, the Hui form the largest, followed by Uyghurs. ↩

-

The Qing Empire annexed two regions within Central Asia, first Dzungaria in 1755 and then Tarim Basin in 1758 integrating them and renaming it, Xinjiang “New Frontier”. The Moingolian Dzungar tribe, who once resided there were ethnically cleansed from the region, see Mark Levene, “Empires, Native Peoples, and Genocide,” in Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History, ed A. Dirk Moses, (Berghahn Books, 2010), 183–204. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qd5qb.11. ↩

-

Islam is a religion that has no intermediaries, each individual Muslim communicates to God directly without an Imam interceding. Hence the Emperor inserting himself into their worship undermines the basic principles of the religion. ↩

-

Gang Zhao, “Reinventing China: Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century”, Modern China 32, no. 1 (2006): 3–30, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20062627. ↩

-

Beijing itself is home to the Ox Street Mosque which was first established in the 10th century and the historian Yang Naiji notes that, that the Huiziying, in size and style, is wholly unremarkable in comparison to it. See Yang Naiji 楊乃済 “Xiangfei Chuanshuo yu baoyuelou, huiziying” 香妃 伝説与宝月楼・回子営 [Xiangfei Legend, the Lofty Building of Treasure Moon and Turkic-Muslim Camp].Gugong bowuyuan yuankan 故宮博物院 月刊, 3 (1982): 44-48. ↩

-

The qiblah has not always been Makkah, but in the early years of Islam was Jerusalem. In 623 CE the Prophet Muhammad was commanded by God to change direction of prayer from Jerusalem to Makkah. ↩

-

After the part of the Imperial Wall, south of Baoyuelou (now Xinhua Gate)–the rumoured residency of the Fragrant Concubine—was demolished, the proximity of the qingzhensi to the Zhongnanhai compound displeased Yuan Shikai, who first proposed the mosque to be relocated. This roused an objection from Ma Rong’en angering Shikai who then ordered it to be demolished, see Onuma, 47. ↩

-

There were approximately 40 mosques present in Beijing at that time. We can presume that most Muslims would have preferred attending another mosque instead of Huiziying Qingzhensi. ↩

-

Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, (Great Britain: Serpent’s Tail, 2019), xiii. ↩

-

I have not personally investigated the archives but have reliant on the writings of historians such as Takahiro Onuma, who in his text apart from the current residency and the fragrant concubine references only the voices of male leader of the community. ↩

-

Brown, 143. ↩

-

Saidiya, Hartman “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008), 13. ↩

-

Onuma, 54. ↩

-

Broomhall, 263. ↩

-

Co-opting the language of war and terror, Uyghurs are being labelled as terrorists for simply growing a beard, using WhatsApp, or travelling abroad and sent to internment camps, see Raffi Khatchadourian, “Surviving the Crackdown in Xinjiang”, The New Yorker, April 5, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/04/12/surviving-the-crackdown-in-xinjiang. ↩

-

The large scale of internment was pieced together by Megha Rajagopalan, Alison Killing and Christo Buschek, Rajagopalan, Megha. Killing, Alison. Buschek, Christo. “China Built A Vast New Infrastructure To Imprison Uighurs”, Buzzfeed News, August 27, 2020. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/meghara/china-new-internment-camps-xinjiang-uighurs-muslims. ↩

-

Fouzia Khan, “Largest ever number of Chinese pilgrims coming for Haj this year”, Arab News, October 10, 2012. ↩

-

Emily Feng, “China is removing domes from mosques as part of a push to make them more ‘Chinese’”, National Public Radio (NPR), October 24, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/10/24/1047054983/china-muslims-sinicization. ↩

-

David Brophy, Good and Bad Muslims in Xinjiang, (ANU Press, 2022) https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv28x2b9h.11. ↩

Shukri Sultan was a Curatorial Intern (2022-23) and part of the Critical Cataloguing team.

Testimonies of the Egg

Endriana Audisho, Julia Ramos, and Jacqueline Tran retrace the counter-narratives of an unfinished building

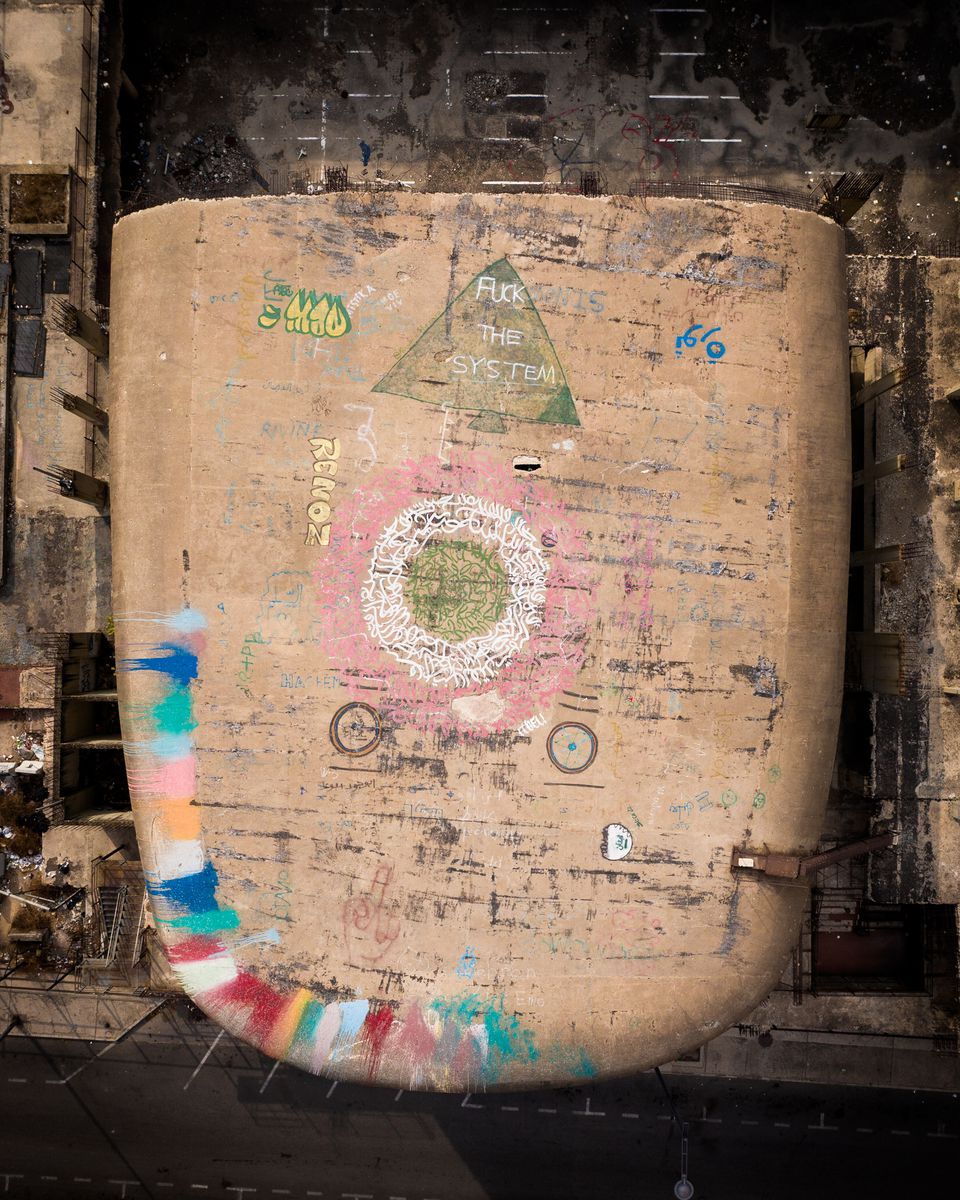

This is an incomplete story of an unfinished building. In downtown Beirut, metres from Martyrs’ Square, stands a dilapidated, graffitied concrete shell. Also known as the Egg of Beirut, “the Dome,” or “Sabouneh”—Arabic for “soap,” the brutalist-modernist movie theatre was originally designed in 1965 by Joseph-Philippe Karam. Initial readings of images of the building, which often capture it within the skyline of Beirut Central District, may suggest that the egg-shaped building is out of place. The crane foregrounding and framing this particular image either speaks to the redevelopment surrounding the Egg or its potential demise—a structure under demolition and on its way out. This preliminary reading of a single photograph is, however, surface level. It falls short of capturing the layered history of a building that has survived several threats to its existence and, in turn, has rebirthed into a symbol of resistance, revolution, and reclamation in Beirut. An investigative visual practice1—one that advocates for reading across, between, and within images as a method for comparison2—facilitates a retracing and resurfacing of the multiple voices and counter-narratives of the Egg.

A complex past haunts the Egg, one that is recorded on its material surface and captured so vividly through images of the building across time. Buildings are not mute.3 They are a form of archive in and of themselves. As registers of matter and transmitters of memories over time, they contribute to the making of history, or histories in the plural, when closely read. The surface of the Egg, peeling away at times and peppered with bullet holes, is a reminder of Lebanon’s past. The Egg was originally designed as part of “Beirut City Centre,” a proposal for a multi-use complex hybridizing the movie theatre with a shopping mall and office spaces.4 It was auspiciously used as a cinema until the Lebanese Civil War broke out in 1975. Construction immediately ceased, leaving the complex unfinished. With its prime location along the Green Line,5 and with its distinctive reinforced concrete shell coincidentally resembling a bunker, the Egg was occupied by snipers during the war.6 As a frontline spectator, it became not only a witness but also a victim of Lebanon’s socio-political history. Its surface registered the material effects, with each bullet hole.

-

In Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth, Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, describe investigative aesthetics as a practice of weaving “signals,” “traces,” and visual cues in relation to one another in order to uncover “counter-readings and counter-narratives” that may not be immediately evident. This approach is critical for unravelling the complexities of images as historical and political evidence, fostering a nuanced understanding of the visual world and its intersections with “truth” and “conflict”. Matthew Fuller and Eyal Weizman, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (London: Verso Books, 2019): 1-30. ↩

-

In Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images As Historical Evidence, historian Peter Burke claims that images sit alongside literary texts and oral testimonies as valid forms of historical evidence. While supporting the use of images, Burke points out that we must always situate the testimony of images in a context, or better, “in a series of contexts in the plural” (p.187). Working in the plural allows for comparison, either highlighting affinities, exposing absences, or constructing new associations. Peter Burke, Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images As Historical Evidence (London: Reaktion Books, Limited, 2014). ↩

-

In the introduction to Architectural Voices: Listening to Old Buildings, David Littlefield proposes to reimagine a building as a personality, asking “If it [a building] could speak, what would it say? What would it sound like? Would it be worth listening to?” (p.10). Although this book is more pointedly asking these questions in the context of re-use projects, it does call for a broader and expanded understanding of what it means to “interpret” a building. This is explicated in Saskia Lewis’ epilogue which suggests that buildings bear witness to events and hold evidence that become narratives, otherwise “It is true that without people to articulate them, exchange stories and interact with them buildings remain mute” (p.228). David Littlefield and Saskia Lewis, eds., Architectural Voices: Listening to Old Buildings (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2007). ↩

-

Please refer to the Joseph-Philippe Karam fonds, specifically the City Centre (Samadi & Salha) collection, to view the original drawings of the complex. https://arab-architecture.org/db/building/city-centre-samadi-and-salha ↩

-

The Green Line was a border of demarcation during the Civil War from 1975-1990. It acted as a form of division between the Muslim West and the Christian East of Beirut. ↩

-

In addition to the Egg’s location along the Green Line, the building stands near a significant intersection that not only connects the East and West part of the city, but makes it accessible from three roads (Bechara Khoury, Mere Gelas, and Saint Vincent). ↩

With its platforms and pilotis exposed and its surface riddled with cavities, the Egg was beyond repair after the war and, therefore, remained largely abandoned. Images of the Egg that circulate popular media merely present the building through this vulnerability—undressed, war-torn, and unfinished. Images, however, are also not mute.1 Closely reading the Egg through the images that circulated shortly after the war right up until the 2019 civil protests in Lebanon suggest otherwise. The Egg’s exterior and interior are repeatedly seen shrouded with paint, from colourful murals and messages of resistance to political statements condemning the government amid the 17 October Revolution. These once informal and temporal traces on the surface of the Egg resurface as counter-narratives of resistance, revolution, and reclamation. The constellation of images, or rather the visual archive, recording the Egg’s occupation and surface over time are the very documents that construct these counter-narratives.

The visual archive under inquiry here is not assembled through “conventional” sources or accessed through the “official” state-led archive. It has appeared through a combination of citizen-led campaigns and collective political activism produced through social media platforms, predominantly Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.2 In 2009 the social media campaign #SaveTheEgg emerged in response to a series of demolition threats associated with the city’s broader post-war redevelopment plans that began in the early 1990s.3 What started as a humble Facebook group, established by student Dania Bdeir,4 transformed into an “online” protest to #SaveTheEgg. The use of the hashtag provided a platform to share personal affinities with the building, thereby stimulating broader public awareness, support, and action for its preservation and restoration. The online movement was accompanied by exhibitions and concerts inside the Egg, all of which were memorialised through documented visual traces found within the hashtag. The campaign, which also included petitions and sought alternative design responses to that of private developers, was effective as the fate of the Egg was ultimately secured for a little longer. The building remained closed to the public for the subsequent years until #Eggupation unfolded.

-

Although focused on historically dismissed images, mainly identification photos, of the African diaspora, Tina Campt, through the provocation of “listening to images,” provides a methodology that can be used to critically engage with images today—both the re-imagining of the practice of observation as well as the opportunity to reclaim the agency of images through new readings. Choosing to closely “listen” to images is an act of interrogation that goes beyond looking at a “mute” image but, rather, constitutes “a practice of looking beyond what we see and attuning our senses to other affective frequencies through which photographs register’‘ (p. 9). As Campt aptly provokes, “some photos are not quiet at all” (p. 116). See T. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017). ↩

-

The launch of social networking platforms across the 2000s has facilitated the rise of citizen journalism in times of socio-political upheaval. As sites under conflict are often difficult to access or state-led media blackouts prevent any form of “ground-truthing” from occurring, “on-the-ground” citizen journalism has become a powerful act of political activism and resistance. This can be traced back to the first major social media movement in the age of omnipresent mobile phones, the Arab Spring (2010-2012), through to Occupy Wall Street (2011) and Black Lives Matter (2013-), all of which aimed to mobilize collective action, support, and allyship through social media. More recently, and at the time of this writing, the use of social media to live-stream/document events unfolding in Occupied Palestine has shaped networks of solidarity and collective action at an unprecedented scale. Whilst acknowledging the inherent ethical complexities associated with navigating this contemporary mediascape, including widespread misinformation and propaganda, targeted censorship and hate speech, it is crucial to highlight that social media continues to provide a collective space for self-determination, resistance, and the construction of counter-narratives. ↩

-

As part of the post-war reconstruction efforts for Beirut Central District (BCD), the Lebanese government (under the former prime minister, Rafik El-Hariri) turned to a private Real Estate Holding Company known as “Solidere.” Founded in 1994, Solidere became in charge of the reconstruction of BCD. ↩

-

See Merheb, Aimee “Saving the Egg Documentary” January 19, 2010, video, 9.32, https://youtu.be/AaYVIrFafBM?si=jAKMHgR8q1bz1ho6 ↩

The social media campaign #Eggupation transpired in the context of new tax measures announced by the Lebanese government on 17 October 2019, to address the economic crisis. What followed was a series of protests across the country calling for socio-economic justice. In Beirut, locals were committed to a historic occupation of the Egg, with images on Instagram displaying scenes of protesters climbing the rusted stairs that lead up and into the shell. If we look closely at this image and return to the first, they document a time when protestors had removed the fences and hoarding used to historically shield the Egg. The once-abandoned building was transformed into a “revolutionary classroom,”1 which facilitated a number of cultural events, including a venue for discussions, film screenings, and raves. The building was also exercised as a meeting and vantage point, a backdrop for the demands of the people, and a canvas for their political messages. The act of occupation not only supported a space of solidarity, but it also saw a reclamation of public property (the Egg) by the public.

Hashtags such as #SaveTheEgg and #Eggupation can be seen as tools of archiving2 as they connect individual posts into larger collections, ready to be interpreted and assembled into narratives.3 In the case of the Egg, they were mobilised to collate and circulate visual media to advocate for the preservation of the building as well as a broader reclamation of the city during the revolution. This widespread exposure, enabled by the hashtags, inherently forged a “digital” and lateral network of solidarity,4 increasing participatory engagement both online and offline. As we have seen, social media is emerging as an alternative archive. In “Instant Archives,” Haidy Geismar argues that “we need to take seriously how social media has become a new institutional framework.”5 As a living and growing repository registering informal traces, social media platforms are completely subverting “the ways in which archives are used as tools of power, social control, and centralisation.”6 The grass-roots engagement and citizen-led journalism facilitated through and by social media is not only generating an expanded visual field7 but has completely destabilised and re-drawn the boundaries of the “official” archive. Such reimaginings of the archive welcome a more democratised approach to the construction of cultural memory and more broadly, to historiography. Narratives that have consistently been excluded by traditional archives are resurfacing by the public and are becoming accessible to a broader audience.

The participatory witnessing and recording of recent socio-economic and political events in Beirut through social media have re-organized the cultural memory of the Egg, and by extension, the city. Although the Egg’s future remains unclear, its survival is a testimony to the significant cultural role the building has played in the city. In its defiance to be demolished, the Egg remains a spectre of pasts, presents and possible futures. It sits proudly as a reminder of the things that have become and the things that might become. This is an incomplete story of an unfinished building as we hope its surface will continue to register counter-narratives, further reimagining and expanding on the building’s revolutionary identity. The Egg has more to say, if we look beyond what we first see.

-

With the 2019 revolution causing the closure of all major universities in Beirut, many students and academics took their classrooms to the streets. Lectures, debates and teach-ins were being hosted on the sidelines of the protests - most predominantly within the Egg. See Ward, Euan “‘Eggupation’ breeds revolutionary thinking in Beirut”, Al-Monitor, November 6, 2019 https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2019/11/lebanese-protesters-eggupy-old-cinema.html ↩

-

As a classification tool, the hashtag functions as an interface through which visual media is connected, collated, and added to over time. In this sense, the hashtag forms a living repository whereby the act of hashtagging (and captioning) allows for active participation in the ongoing construction of social and cultural memory. ↩

-

The concept of archiving and interpreting through collective narratives is explored in Plot 987: Surfaced Phantoms of the Egg, an expanded drawing by Julia Ramos and Jacqueline Tran produced for the University of Technology Sydney, Master of Architecture design studio Cities Under Surveillance, Autumn Semester, 2020, led by Endriana Audisho and Tova Lubinsky. Through a performative exchange between the drawing and the user, the intervention acts as an apparatus to encounter and trace the multiple “surfaces” of the Egg. See http://www.interlude-archive.co/pages/egg-about.html ↩

-

In Instant Archives? Haidy Geismer explains that hashtags were introduced by Instagram in 2011 to “increase lateral connections across users” and that the consequential clustering of images has become an archival tool. See Haidy Geismer, “Instant Archives?,” in The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography, eds. Larissa Hjorth, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell (New York: Routledge, 2016), 336. ↩

-

Haidy Geismer, “Instant Archives?,” 331. ↩

-

Haidy Geismer, “Instant Archives?,” 333. ↩

-

There are limitations associated with the recently expanded visual field that need to be flagged here. The immeasurable amount of visual information our contemporary mediascape presents and the continual access to views “up-close” warrants further investigation. In a post-truth context, image manipulation, post-production techniques, deep fakes (as enabled by recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning), and different forms of censorship are radically transforming the way we see and experience reality. Therefore, the ability to view many things “up-close” at any time does not necessarily provide more detail or clarity. Instead, it raises questions of excess and the consequent limits of absorption, of authorship and the ability for anyone to produce online content or alternative fact. In a world dominated by two extremes, image excess and censorship, and where the question of ethics is very much entangled with aesthetics, what it means to “look” today needs to be re-considered. This not only becomes a question of what is visible and on show but, more importantly, what is hidden, cropped, or completely absent from the frame of the images. ↩

Authors’ note (November 2023): As a text exploring social media as an alternative archive, one that can facilitate the construction of counter-narratives and give voice to historically overlooked or silenced peoples, we recognize the need to confront the urgent realities of settler-colonial violence, oppression, and genocide committed against Palestinians for over 75 years. We stand in solidarity with Palestine and stand against any form of apartheid, ethnic cleansing, and settler-colonial violence.