$60.00

(available to order)

Summary:

The story of midcentury architecture in America is dominated by outsized figures—Richard Neutra, George Nelson, Louis Kahn—who were universally acknowledged as creative geniuses. Yet virtually unheard of is the intensive 1958–59 study, conducted at the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research at the University of California, Berkeley, that scrutinized these and(...)

The creative architect: inside the great midcentury personality study

Actions:

Price:

$60.00

(available to order)

Summary:

The story of midcentury architecture in America is dominated by outsized figures—Richard Neutra, George Nelson, Louis Kahn—who were universally acknowledged as creative geniuses. Yet virtually unheard of is the intensive 1958–59 study, conducted at the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research at the University of California, Berkeley, that scrutinized these and dozens of other famous architects in an effort to map their minds. Deploying an array of tests reflecting current psychological theories, the investigation sought to answer questions that still apply to creative practice today: What makes a person creative? What are the biographical conditions and personality traits necessary to actualize that potential? The study’s findings have been gathered through numerous original sources, including questionnaires, aptitude tests, and interview transcripts, revealing how these great architects evaluated their own creativity and that of their peers. In The Creative Architect, Pierluigi Serraino charts the development, implementation, and findings of this historic study, producing the first look at a fascinating and forgotten moment in architecture, psychology, and American history.

History since 1900, Reference Books

books

$99.99

(available to order)

Summary:

This second volume of "The Details of Modern Architecture" continues the study of the relationships of the ideals of design and the realities of construction in modern architecture, beginning in the late 1920s and extending to the present day. It contains a wealth of new (...)

June 1996, Cambridge, Mass.

Details of modern architecture - volume 2 : 1928-1988

Actions:

Price:

$99.99

(available to order)

Summary:

This second volume of "The Details of Modern Architecture" continues the study of the relationships of the ideals of design and the realities of construction in modern architecture, beginning in the late 1920s and extending to the present day. It contains a wealth of new information on the construction of modern architecture at a variety of scales from minute details to general principles. There are over 500 illustrations, including 130 original photographs and 230 original axonometric drawings, arranged to explain the technical, aesthetic, and historical aspects of the building form. Individual chapters treat the work of Eliel and Eero Saarinen, Eric Gunnar Asplund, Richard Neutra, Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, and Louis Kahn, as well as the Case Study, High Tech, Postmodern, and Deconstructivist architects. Among the individual buildings documented are Eliel Saarinen's Cranbrook School, Asplund's Woodland Cemetery, Fuller's Dymaxion house, the Venturi house, the Eames and other Case Study houses, the concrete buildings of Le Corbusier, Aalto's Säynätsalo Town Hall, and Kahn's Exeter Library and Salk Institute -- with many details published for the first time.

books

June 1996, Cambridge, Mass.

$77.00

(available to order)

Summary:

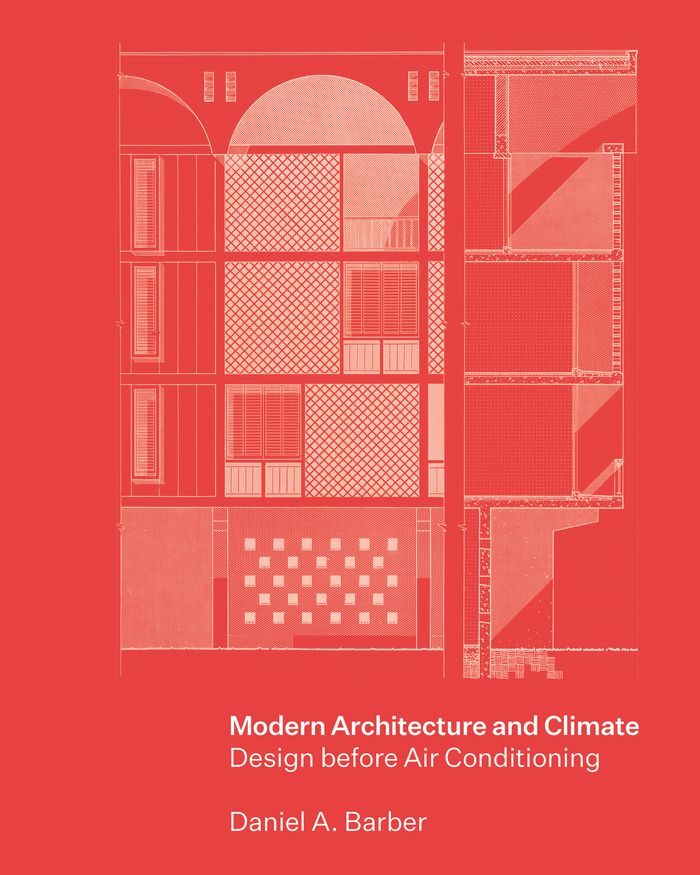

explores how leading architects of the twentieth century incorporated climate-mediating strategies into their designs, and shows how regional approaches to climate adaptability were essential to the development of modern architecture. Focusing on the period surrounding World War II—before fossil-fuel powered air-conditioning became widely available—Daniel Barber brings to(...)

Modern architecture and climate: design before air conditioning

Actions:

Price:

$77.00

(available to order)

Summary:

explores how leading architects of the twentieth century incorporated climate-mediating strategies into their designs, and shows how regional approaches to climate adaptability were essential to the development of modern architecture. Focusing on the period surrounding World War II—before fossil-fuel powered air-conditioning became widely available—Daniel Barber brings to light a vibrant and dynamic architectural discussion involving design, materials, and shading systems as means of interior climate control. He looks at projects by well-known architects such as Richard Neutra, Le Corbusier, Lúcio Costa, Mies van der Rohe, and Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, and the work of climate-focused architects such as MMM Roberto, Olgyay and Olgyay, and Cliff May. Drawing on the editorial projects of James Marston Fitch, Elizabeth Gordon, and others, he demonstrates how images and diagrams produced by architects helped conceptualize climate knowledge, alongside the work of meteorologists, physicists, engineers, and social scientists. Barber describes how this novel type of environmental media catalyzed new ways of thinking about climate and architectural design.

Architectural Theory

$62.00

(available to order)

Summary:

When we think of the gardens of Southern California, we tend to think of the enormous semiarid landscapes of the Huntington and Rancho Los Alamitos, often built on the sprawling grounds of former ranches. But there is another garden tradition in Southern California: the modest, rectangular suburban plots designed by the most famous architects of mid-century modernism:(...)

Private landscapes : modernist gardens in Southern California

Actions:

Price:

$62.00

(available to order)

Summary:

When we think of the gardens of Southern California, we tend to think of the enormous semiarid landscapes of the Huntington and Rancho Los Alamitos, often built on the sprawling grounds of former ranches. But there is another garden tradition in Southern California: the modest, rectangular suburban plots designed by the most famous architects of mid-century modernism: Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler, Gregory Ain, Raphael Soriano, Harwell Hamilton Harris, A. Quincy Jones, and John Lautner. These architects saw the garden as an outdoor extension of the space of the houses they designed, rather than a neo-Spanish fantasy to be added later by a "landscapist." Their modern gardens made use of low-maintenance, drought-resistant plants, and made room for informal outdoor living by children and adults with an emphasis on recreation and exercise. «Private Landscapes» profiles twenty significant gardens-and their accompanying houses-by these celebrated architects. Using contemporary photographs by Julius Shulman and newly commissioned color images, along with plans and plant lists, «Private Landscapes» provides a never-before-seen look at these gardens. As beautiful and practical now as they were 50 years ago, these designs continue to provide inspiration for gardeners and designers everywhere.

Gardens

$44.95

(available to order)

Summary:

CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne), founded in Switzerland in 1928, was an avant-garde association of architects intended to advance both modernism and internationalism in architecture. CIAM saw itself as an elite group revolutionizing architecture to serve the interests of society. Its members included some of the best-known architects of the twentieth(...)

Urban Theory

October 2002, Cambridge, Massachusetts

The CIAM discourse on urbanism, 1928-1960

Actions:

Price:

$44.95

(available to order)

Summary:

CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne), founded in Switzerland in 1928, was an avant-garde association of architects intended to advance both modernism and internationalism in architecture. CIAM saw itself as an elite group revolutionizing architecture to serve the interests of society. Its members included some of the best-known architects of the twentieth century, such as Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Richard Neutra, but also hundreds of others who looked to it for doctrines on how to shape the urban environment in a rapidly changing world. In this first book-length history of the organization, architectural historian Eric Mumford focuses on CIAM's discourse to trace the development and promotion of its influential concept of the "Functional City." He views official doctrines and pronouncements in relation to the changing circumstances of the members, revealing how CIAM in the 1930s began to resemble a kind of syndicalist party oriented toward winning over any suitable authority, regardless of political orientation. Mumford also looks at CIAM's efforts after World War II to find a new basis for a socially engaged architecture and describes the attempts by the group of younger members called Team 10 to radically revise CIAM's mission in the 1950s, efforts that led to the organization's dissolution in 1959.

Urban Theory

books

$41.95

(available to order)

Summary:

Beginning with the inception of the U.S. embassy building program in 1926, and continuing through the 1996 competition for a new embassy in Berlin, "The Architecture of Diplomacy" examines a remarkable(...)

Commercial interiors, Building types

August 1998, New York

The architecture of diplomacy : building America's embassies

Actions:

Price:

$41.95

(available to order)

Summary:

Beginning with the inception of the U.S. embassy building program in 1926, and continuing through the 1996 competition for a new embassy in Berlin, "The Architecture of Diplomacy" examines a remarkable yet little-known chapter in architectural history. It focuses on the 1950s, when modernism became linked with the idea of freedom and the State Department's Office of Foreign Buildings Operations began to showcase modern architecture in its embassies. Architects could build abroad in styles never sanctioned at home, resulting in unusual and sometimes outlandish designs intended to express an "open" America overseas. Indeed, the embassy building program was part of the nation's larger effort to establish and assert its superpower status following World War II. Terrorist threats and espionage scandals also shaped the worldwide building program, and continue to affect it today. "The Architecture of Diplomacy" features the stories behind the Rio de Janiero and Havana embassies by Harrison & Abramovitz, Ralph Rapson's designs for Stockholm and Copenhagen, Gordon Bunshaft's work in Germany, Eero Saarinen's constructions in London and Oslo, and Edward Durell Stone's embassy in New Delhi. Other architects involved in the program included Arquitectonica; Pietro Belluschi; Marcel Breuer; Walter Gropius; Kallmann, McKinnell & Wood; Richard Neutra; and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Author Jane C. Loeffler obtained access to original correspondence, drawings, and photographs that have never been published.

books

August 1998, New York

Commercial interiors, Building types

$45.95

(available to order)

Summary:

Even when an architectural drawing does not show any human figures, we can imagine many different characters just off the page: architects, artists, onlookers, clients, builders, developers, philanthropists—working, observing, admiring, arguing. In ''Stories from architecture,'' Philippa Lewis captures some of these personalities through reminiscences, anecdotes,(...)

Stories from architecture: Behind the lines at Drawing Matter

Actions:

Price:

$45.95

(available to order)

Summary:

Even when an architectural drawing does not show any human figures, we can imagine many different characters just off the page: architects, artists, onlookers, clients, builders, developers, philanthropists—working, observing, admiring, arguing. In ''Stories from architecture,'' Philippa Lewis captures some of these personalities through reminiscences, anecdotes, conversations, letters, and monologues that collectively offer the imagined histories of twenty-five architectural drawings. Some of these untold stories are factual, like Frank Lloyd Wright’s correspondence with a Wisconsin librarian regarding her $5,000 dream home, or letters written by the English architect John Nash to his irascible aristocratic client. Others recount a fictional, if credible, scenario by placing these drawings—and with them their characters—into their immediate social context. For instance, the dilemmas facing a Regency couple who are considering a move to a suburban villa; a request from the office of Richard Neutra for an assistant to measure Josef von Sternberg’s Rolls-Royce so that the director’s beloved vehicle might fit into the garage being designed by his architect; a teenager dreaming of a life away from parental supervision by gazing at a gadget-filled bachelor pad in Playboy magazine; even a policeman recording the ground plans of the house of a murder scene. The drawings, reproduced in color, are all sourced from the Drawing Matter collection in Somerset, UK, and are fascinating objects in themselves; but Lewis shifts our attention beyond the image to other possible histories that linger, invisible, beyond the page, and in the process animates not just a series of archival documents but the writing of architectural history.

Architectural Theory

$49.95

(available to order)

Summary:

This second volume of "The details of modern architecture" continues the study of the relationships of the ideals of design and the realities of construction in modern architecture, beginning in the late 1920s and extending to the present day. It contains a wealth of new information on the construction of modern architecture at a variety of scales from minute details to(...)

Architecture since 1900, Europe

October 2003, Cambridge, Mass.

The details of modern architecture volume 2 : 1928 to 1988

Actions:

Price:

$49.95

(available to order)

Summary:

This second volume of "The details of modern architecture" continues the study of the relationships of the ideals of design and the realities of construction in modern architecture, beginning in the late 1920s and extending to the present day. It contains a wealth of new information on the construction of modern architecture at a variety of scales from minute details to general principles. There are over 500 illustrations, including 130 original photographs and 230 original axonometric drawings, arranged to explain the technical, aesthetic, and historical aspects of the building form. Most of the modern movements in architecture have identified some paradigm of good construction, arguing that buildings should be built like Gothic cathedrals, like airplanes, like automobiles, like ships, or like primitive dwellings. Ford examines the degree to which these models were followed, either in spirit or in form, and reveals much about both the theories and techniques of modern architecture, including the extent to which the current constructional theories of high tech and deconstruction are dependent on the traditional modernist paradigms, as well as the ways in which all of these theories differ from the realities of modern building. Individual chapters treat the work of Eliel and Eero Saarinen, Eric Gunnar Asplund, Richard Neutra, Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, and Louis Kahn, as well as the Case Study, high tech, postmodern, and deconstructivist architects. Among the individual buildings documented are Eliel Saarinen's Cranbrook School, Asplund's Woodland Cemetery, Fuller's Dymaxion house, the Venturi house, the Eames and other Case Study houses, the concrete buildings of Le Corbusier, Aalto's Säynätsalo Town Hall, and Kahn's Exeter Library and Salk Institute.

Architecture since 1900, Europe

$79.95

(available to order)

Summary:

Although both are central to architecture, siting and construction are often treated as separate domains. In "Uncommon Ground", David Leatherbarrow illuminates their relationship, focusing on the years between 1930 and 1960, when utopian ideas about the role of technology in (...)

Uncommon ground : architecture, technology. and topography

Actions:

Price:

$79.95

(available to order)

Summary:

Although both are central to architecture, siting and construction are often treated as separate domains. In "Uncommon Ground", David Leatherbarrow illuminates their relationship, focusing on the years between 1930 and 1960, when utopian ideas about the role of technology in building gave way to an awareness of its disruptive impact on cities and culture. He examines the work of three architects, Richard Neutra, Antonin Raymond, and Aris Konstantinidis, who practiced in the United States, Japan, and Greece respectively. Leatherbarrow rejects the assumption that buildings of the modern period, particularly those that used the latest technology, were designed without regard to their surroundings. Although the prefabricated elements used in the buildings were designed independent of siting considerations, architects used these elements to modulate the environment. Leatherbarrow shows how the role of walls, the traditional element of architectural definition and platform partition, became less significant than that of the platforms themselves, the floors, ceilings, and intermediate levels. He shows how frontality was replaced by the building's four-sided extension into its surroundings, resulting in frontal configurations previously characteristic of the back. Arguing that the boundary between inside and outside was radically redefined, Leatherbarrow challenges cherished notions about the autonomy of the architectural object and about regional coherence. Modern architectural topography, he suggests, is an interplay of buildings, landscapes, and cities, as well as the humans who use them. The conflict between technological progress and cultural continuity, Leatherbarrow claims, exists only in theory, not in the real world of architecture. He argues that the act of building is not a matter of restoring regional identity by re-creating familiar signs, but of incorporating construction into the process of topography's perpetual becoming.

Architectural Theory

books

$56.95

(available to order)

Summary:

Although both are central to architecture, siting and construction are often treated as separate domains. In "Uncommon Ground", David Leatherbarrow illuminates their relationship, focusing on the years between 1930 and 1960, when utopian ideas about the role of technology in (...)

Architectural Theory

October 2000, Cambridge, Mass.

Uncommon ground : architecture, technology, and topography

Actions:

Price:

$56.95

(available to order)

Summary:

Although both are central to architecture, siting and construction are often treated as separate domains. In "Uncommon Ground", David Leatherbarrow illuminates their relationship, focusing on the years between 1930 and 1960, when utopian ideas about the role of technology in building gave way to an awareness of its disruptive impact on cities and culture. He examines the work of three architects, Richard Neutra, Antonin Raymond, and Aris Konstantinidis, who practiced in the United States, Japan, and Greece respectively. Leatherbarrow rejects the assumption that buildings of the modern period, particularly those that used the latest technology, were designed without regard to their surroundings. Although the prefabricated elements used in the buildings were designed independent of siting considerations, architects used these elements to modulate the environment. Leatherbarrow shows how the role of walls, the traditional element of architectural definition and platform partition, became less significant than that of the platforms themselves, the floors, ceilings, and intermediate levels. He shows how frontality was replaced by the building's four-sided extension into its surroundings, resulting in frontal configurations previously characteristic of the back. Arguing that the boundary between inside and outside was radically redefined, Leatherbarrow challenges cherished notions about the autonomy of the architectural object and about regional coherence. Modern architectural topography, he suggests, is an interplay of buildings, landscapes, and cities, as well as the humans who use them. The conflict between technological progress and cultural continuity, Leatherbarrow claims, exists only in theory, not in the real world of architecture. He argues that the act of building is not a matter of restoring regional identity by re-creating familiar signs, but of incorporating construction into the process of topography's perpetual becoming.

books

October 2000, Cambridge, Mass.

Architectural Theory