Interim Urbanism, Youth, and Homes In-Between

Nahyun Hwang and David Eugin Moon of N H D M speculate on the precarity and possibilities of youth dwelling

Interim Urbanism

As society continues to adapt to shifting economic and environmental conditions, familiar formats of living have started to be contested.1 The myth of the permanent nuclear household as the ideal spatio-political unit of a productive society is no longer tenable, and increased mobility and transiency—both voluntary and forced—produce elusive yet ubiquitous conditions of in-betweenness for the hidden majority of the population in what we term “Interim Urbanism.”2 For some, dwelling in the tentative space of the interim is tolerable at best due to its purported temporality, and for others, expectations of detachment and possibilities of noncommittal encounters make it that much more alluring. “Interim Urbanism” shapes and is shaped by the provisional and indeterminate spaces of “the stay,” which evade settlement and fixity.3 From the makeshift homes of refugees to the fragile autonomy of tent cities, from the remote retreats of youthful digital nomads to the carefully personalized bunk beds in group homes, permanence and belonging are suspended and pursued at once. Sometimes as fortressed as what Koolhaas calls the “commune” of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, or as fleeting as the instant families formed at the shared kitchens of coliving spaces like WeLive, the spaces of the stay are often transient yet necessary utopias.4 The sites of the stay are the ultimate environments for politics and biopolitics, where delegates mingle and nations are presented, and where the promiscuity of work and life surface to Kracauer’s content.5 Sometimes with expressive facades but more often through wistfully intimate and hidden interiors, the spaces of Interim Urbanism transcribe lives “in the meantime.”

-

In 2019, only nineteen percent of the US population were traditional households of married couples with children, and there were an estimated 280 million migrant workers worldwide. See Alicia VanOrman and Linda Jacobsen, “America’s Changing Population,” Population Bulletin, June 2019. See also “Total number of international migrants at mid-year 2020,” The Migration Data Portal, 20 January 2021, https://www.migrationdataportal.org/international-data?i=stock_abs_&t=2020. ↩

-

Interim Urbanism is a term coined by the authors in 2015 and encompasses an ongoing series of pedagogical, research, and design projects that investigate the increasingly itinerant and transient nature of habitation. ↩

-

“The stay” is a working term that acknowledges the underexplored concept of a genre of architecture and urbanism that describes a spectrum of temporary habitation in all of its forms and intricacies, and conceived by the authors in 2016 for a Columbia University design studio “Interim Urbanism: Habitation of the City.” ↩

-

Rem Koolhaas, “The Lives of a Block: The Waldorf-Astoria Hotel and the Empire State Building,” in Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan (New York: The Monacelli Press, 1997), 144. ↩

-

Temporary dwelling spaces play significant roles in geopolitics as informal settings for diplomatic exchanges and gatherings, and as spaces that present national and ideological intentions and ideals. See Ruth Craggs, “Hospitality in geopolitics and the making of Commonwealth international relations,” Geoforum 52 (2014): 90-100. See also Siegfried Kracauer, “The Hotel Lobby,” in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995). ↩

Youth and their Homes In-Between

In this context, youth offer a unique lens for the examination and projections of the varied and evolving domesticities that reside in the spaces of the interim, representing one of the most dynamic yet precarious sections of today’s populations. No longer belonging to safe spaces of childhood, but not yet, if ever, integrated into the expected paradigms of traditional family structures, a large portion of today’s young adults, while seemingly spontaneous in lifestyle choices and welcoming mobility, occupy the vulnerable spaces of the in-between and prolonged interim.

As a generation most exposed to socio-political and economic uncertainties and evolving lifestyles, and as a group that is most likely to contest the status quo and inherited social norms, today’s youth and their ways of dwelling and belonging form a poignant cross-section of living that is not only critical in its own right, but also instrumental for the larger investigation of transforming frameworks of life. Not fitting in the prescriptions of nuclear homes and often at the margins of highly commodified conventional housing markets, youth’s domestic realms often operate extra-typologically (and at times extra-legally). These realms boldly or precariously parallel the spaces of conventional residential architecture or “housing,” contending their prescribed urbanisms at the margins.

In Seoul, Korea, despite the general prosperity of the city, more than 37% of the youth between age twenty and thirty-four live in makeshift, temporary, and often below-standard dwellings, such as the Ji-Ha-Shil (legal and illegal basement), the Ok-Top-Bang (impromptu rooftop additions), or the Go-Shi-Bang (modified study carrel rooms).1 A coincidental but apt acronym of these three informal dwelling spaces, “Ji-Ok-Go”—roughly translated from Korean as “hell-like suffering”—reflects the extremely fragile semi-informal domestic realms that single-person households of youth inhabit.2 The proliferation of “Ji-Ok-Go” as a common term and experience, and as some of the most recognizable dwelling typologies shared across this generation, brings forward the limitations in existing housing paradigms and their architectural conventions. As regulatory changes are slowly attempted, the alternative dwelling frameworks specific to youth such as “share houses,” however limited, emerge and permutate.3

On the other side of the globe in cities across Holland, many young professionals and students took advantage of “the House Right, ” or Dutch citizens’ long-held right to live legally in vacant spaces, residing in empty office towers and occupying industrial buildings until the conservative government’s 2010 squat ban.1 Often resulting in minimal but communal living arrangements, the now-prohibited practice of “kraken” inspired the establishment of many new cooperative housing projects and the “Post-Squat” experimentations in dwellings such as OT301, a school building turned into collective housing.2 While situated in drastically different economic and cultural contexts, circumstances of youths’ dwelling in Seoul and Holland both point to the mismatch between the outmoded yet obdurate socio-political, financial, and architectural frameworks of our cities and the contemporary conditions of living and working. Youth and their myriad homes in-between exemplify their ability, or mandate, to expand the rules of dwelling and the very notions of domesticity and belonging.

-

Until 2010, legislation allowed for squatting to become legal under certain circumstances in Holland. See Hans Pruijt, “Is the Institutionalization of Urban Movements Inevitable? A comparison of the Opportunities for Sustained Squatting in New York City and Amsterdam,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27.1 (2003): 145. ↩

-

The minimal living arrangements with a limited number of personal objects resemble the scenes of alternative living from Hannes Meyer’s Co-op Interieur, and the endlessly changing communal interiors the subversive occupation of generic towers in the projects like Archizoom Associati’s “No Stop City.” The term “Post-Squat” comes from David Eugin Moon, “Post-Squat NL: Reprogrammable City,” in Bracket 4, ed. Neeraj Bhatia and Mason White (New York: Actar, 2019), 236-243. ↩

Youth, Dwelling, City—New York

Throughout history, youth in large metropolises, pursuing the possibilities afforded by the urban and distanced from structures of family life, have inhabited the city in remarkably heterogeneous ways. Interim Urbanism: Youth, Dwelling, City- New York” (N H D M, 2019) is part of a larger investigation on “Interim Urbanism” and its intersections with youth’s domestic realms, exploring selected critical instances and projections set forth in New York City and engaging the rich history and demographic complexities of its youth population. Manifesting alternative formats of home and questioning conventional household structures, youth and their ways of dwelling in the city often reveal and presage alternative domesticities and evolving notions and formats of home. Questioning conventions of home, youth’s inhabitation often prefigures other manifestations of new domesticities to come. In the externalized kitchen of FOOD, the famed bohemian restaurant in the 1970s’ pre-gentrification SoHo, young artists including Tina Girouard, Carol Goodden, and Gordon Matta-Clark convened a spontaneous and non-hierarchical “family” and assembled an ephemeral but radically open household at every mealtime.1 Materializing alternative formats of living, youth’s dwellings evince evolving notions and shifting ideals of home. In contemporary membership residences like WeLive, “community living rooms” carefully appointed with trendy furniture and an always-fully-stocked bar guarantee optional but instantly gratifying interactions with others.2 In a parallel but connected topology, a hidden population of “doubled- up” youth redefine the home as fleeting and portable as they crash on friends’ or relatives’ couches night by night, while the upscale interiors of an Apple Stores become a momentary home for some when “disconnected” youth who gather to charge their phones and check their messages for potential jobs and shelters.3 As instruments like food apps connect the shared apartment of the young immigrants delivery workers and the living rooms of tech communes, beyond the apparent disparity and disjuncture in the landscapes of youth dwelling is a connected milieu where the shared socio-economic and technological forces, and both the spontaneous and involuntary transiency of our times, shape new meanings of home.

-

Richard Kostelanetz, Soho: The Rise and Fall of an Artist’s Colony, 1st edition (New York: Routledge, 2003), 90. ↩

-

Interim City, New York illustrates selected examples of the spaces of tentative domesticities—sometimes actively shaped by and at times violently forced upon the young adults of the city of New York—framing about twenty historic and contemporary instances from different eras and neighborhoods of New York. ↩

-

“Doubled-up” refers to living with relatives or friends in temporary arrangements due to loss of housing or economic hardship. See Susanna R. Curry, Matthew Morton, Jennifer L. Matjasko, Amy Dworsky, Gina M. Samuels, and David Schlueter, “Youth Homelessness and Vulnerability: How Does Couch Surfing Fit?” American Journal of Community Psychology 60, no. 1–2 (2017): 17–24. Disconnected youth are defined as young people who are neither in school nor working, usually between the ages of 16 and 24. See Michelle Chen, “Disconnected Youth is a Growing Crisis,” The Nation, 28 February, 2019. ↩

This connected milieu is defined by an architecture of home that is paradoxically scattered. Rather than the “wholesome” completeness of a stereotypical single-family home, the architecture of the youth’s home is fragmented and partial, hinging on its open-endedness. In contrast to the legibility and identifiability of the mechanisms of conventional housebuilding and homemaking, the instruments of belonging for youth are illicit and pliable. The Interim Urbanism that youth participate in and shape is both liberating and precarious.1

-

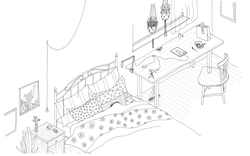

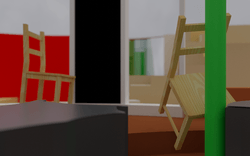

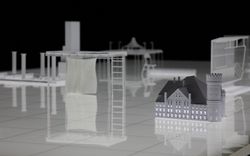

Architecture of Home (For Now) (model and moving image) presents the typological and formal excerpts of the architecture that define and facilitate the fluid yet precarious domestic realm of youth in New York City and their emergent notions of home. ↩

Changing meanings of home and belonging, and the manifold forms of youth’s transient domesticity, are not only critical contexts but may also be effective instruments for reshaping society. The acknowledgement of the shared but systematically biased and diametrically opposed experiences of today’s youth encourages the recognition of increasing precarity in the context of increasing mobility usually hidden away as private matters. Youth’s openness affords experimentation and their fast-evolving notions of domesticity provoke the exploration of alternative programmatic and typological frameworks of living that reconsider the places of the individual and the collective. Radical propositions of the new interim urbanism may frame the possibilities of architecture that engender more equitable sharing of resources and open collaboration in the context of increasingly fragmented collective spheres.

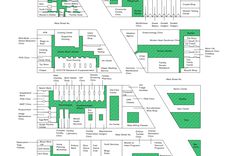

Five Proposals for Youth, Dwelling, City © N H D M.

Engaging drastically different socio-political and physical contexts, five propositions explore new programmatic and typological possibilities in collective living through distinctive experimental dwelling prototypes for youth.

1. Midtown Social Club / 2. Calyer Living Lab / 3. Town, Houses / 4. HQY / 5. Park Avenue Farmhouse

“Interim Urbanism: Youth, Dwelling, City- New York” (N H D M, 2019) is part of a larger investigation on “Interim Urbanism” and its intersections with youth’s domestic realms. The project explores selected critical instances and projections set forth around youth dwelling in New York City, utilizing its rich demographic complexities of the youth population and exploring the specificities in their lives as well as general conditions of living in large metropolises.