CCA c/o Dakar

2023-2026

The CCA c/o program has moved. CCA c/o Dakar will enrich the CCA’s investigation into questions related to the African continent as well as the environment (see our research project Centring Africa: Postcolonial Perspectives on Architecture and the accompanying publication Fugitive Archives: A Sourcebook for Centring Africa in Histories of Architecture) as we will explore the current architectural, urban, and social context of Dakar.

In summer 2023 we began collaborating with Nzinga B. Mboup to produce a series of public programs and research projects in Dakar. Mboup is an architect and curator, co-founder of Worofila, a practice that specialises in bioclimatic architecture and construction using earth and biomaterial sourced locally. Here, she reflects on her aims for our collaboration.

There are a series of questions that we face as architects living and working in Dakar at this point. As CCA c/o Dakar curator, I will explore two primary questions:

What is the material heritage of our cities and what can we learn from it?

What type of Senegalese architectural identity(ies) define our city?

As we move forward with this research program and begin to explore some answers to these questions and highlight the projects that begin to address them, it is important to employ a transdisciplinary approach to interrogate the role that the architecture we are producing plays in the construction of our societies and economies and to give the architect authority to act in the interest of the people.

This program will also be a way to activate the production and dissemination of knowledge in order to breed the ground for the collective appropriation of new forms of building and practice that respond to the preoccupation and evolution of Senegalese and African society.

Research Project 1 – DPLG-S: Senegalese architects and their architectures

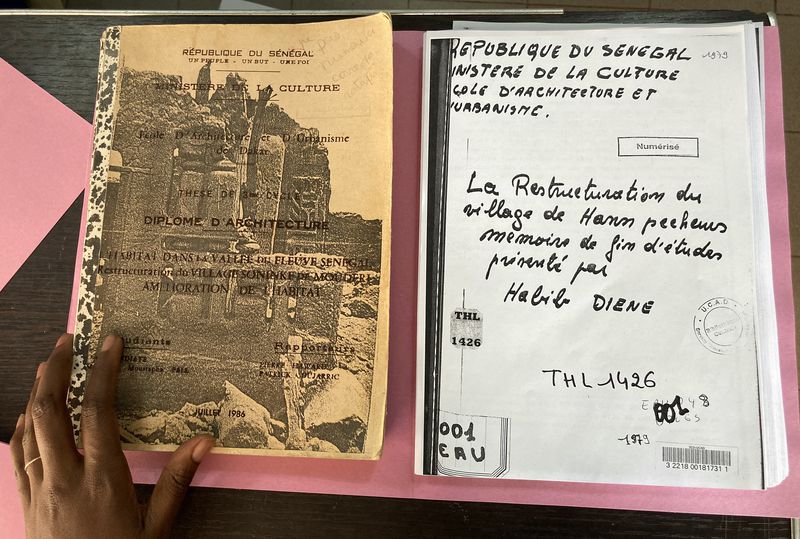

For many young Senegalese architects like myself, we studied architecture abroad and never got to learn about the architectural history of Senegal. There are very little resources on the life and work of Senegalese architects and their architecture and many of the first Senegalese architects to formally register and open their practice are still alive today. The National School of Architecture operated in Dakar between 1971 and 1991 and created a generation of architects who were trained locally, engaged with their architectural history, and questioned their context. There are very little to no archives on the work that they produced.

This research project aims to paint a portrait of the first generations of Senegalese architects and understand their origins, where did the impetus to study architecture come from, what were their careers and forms of practice, what did they produce, and what is their legacy?

There is an opportunity to present these figures whilst understanding the historical, socio-cultural, and political context that they operate in, and also question what they think the role of an architect can be.

The outputs of this project will be a publication and a series of public events in the form of conversations and exhibitions to allow these architects to share their work and journey with the younger generation and to use the opportunity for inter-generational conversation, reflection, and framing of the challenges that lie ahead.

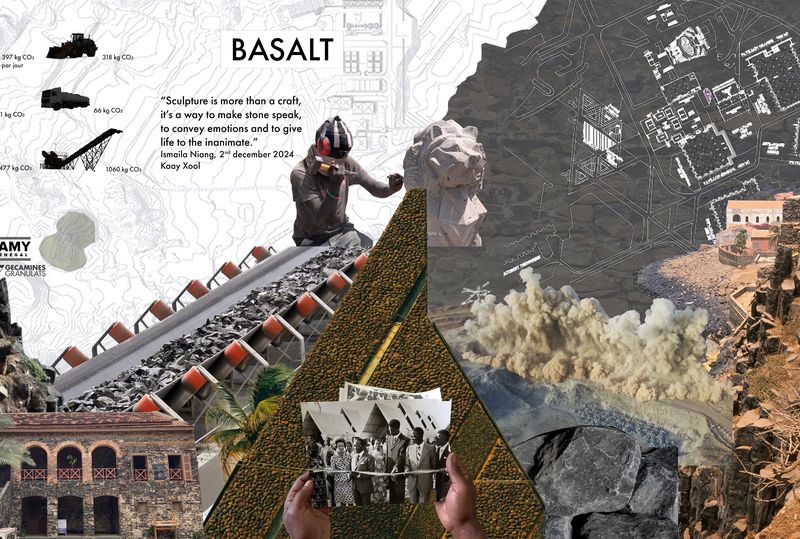

Research Project 2 – A compendium of building materials and constructive techniques of Senegal

Senegalese architecture has been produced through a series of materials both indigenous and imported. The reading of our architectural history can be done through the understating of the various materials used throughout space and time, their origins, their transformation and ultimately the character that they confer to buildings.

In a time when there is a regained interest in bio-sourced materials, their architectural expressions, their impact on the environment and local economies, assembling an atlas of the materials and constructive techniques of Senegalese architects can become a critical tool to define what type of architecture we want to create.

Senegalese context

Dakar is a vibrant and bubbling city that has long been one of Africa’s cultural capitals. From monumental historical events like the FESMAN in 1966 and the Biennale of Contemporary African Art, also known as Dak’Art, which is the continent’s largest contemporary art event, art and culture is everywhere in the city and cultural institutions1 are constantly opening doors and flourishing. The country is also known for its forward-thinking scientists and philosophers such as Cheikh Anta Diop and Felwine Sarr whose works have reminded us, as Africans today, of the rich cultural and scientific common heritage we hold and the necessity to (re)invent our modernity, in our own terms.

This heritage of art and culture at the forefront of the country’s identity is often attributed to our country’s first president, Leopold Sédar Senghor who was also an artist and poet and deliberately established a cultural policy to develop a modern Senegal. One of his theories, that of “asymmetrical parallelism” has inspired architects2 to create a distinctive post-modernist style, in which geometry is based on fractals and rhythm. The Law of Architecture of 1978 promulgated by Senghor stated that architectural creation must draw inspiration from the values of negro-African civilisation, particularly the “sudano-sahelian” whilst fulfilling the requirements of modernity.

We hold a range of architectural traditions dating from pre-colonial times with vernacular African architecture that showcased how to build durably with biomaterials in accordance with the climate. These traditions give us a range of constructive techniques but also of urbanism and establishes how to live communally and are still present in the city today as seen in the form of Penc3 and compound houses. These traditional forms are interwoven with other histories such as the colonial French buildings dating back to the 17th century, the Neo-Sahelian architecture of the 1930s of the Marché Sandaga, the bubble houses of Wallace Neff in the 1950s and the post-modern articulation of first Senegalese architects like in the Immeuble Faycal by Cheikh Ngom and the BCEAO tower of Atepa.

A true palimpsest city, Dakar has been a fertile ground for experimentation and forward-thinking and the place where a lot of questions about the future of cities are still being posed, some are unique to the context and others are universal. More specifically, we are faced with the challenges of defining what is the role of the architect, and of architecture, in a country of 18 million people, with less than 300 registered architects, and the absence of a National School of Architecture since 1991. For architects living and working in Dakar, research is critical to learning about the context despite the lack of resources specifically on architecture. To access knowledge and engage in a debate on the place of architecture in our societies, we have to think creatively and work across disciplines ranging from art, craft, anthropology, sociology, and history, and find a new language to convey ideas about architecture to the people and create archives and repositories to make knowledge available.

Community is key to how we, as Africans, relate to one another. As a young architect living in Dakar, I find it important to inscribe myself into a history and tradition where I am able to learn from my living ancestors, the first generation of architects in Senegal such as Cheikh Ngom, Pierre Goudiaby Atepa, Mbacké Niang, Annie Jouga, Jean-Charles Tall to name a few and confront the legacy of their practice with the challenges we face today. My contemporaries are also my teachers, and as a collective we are working together to start research projects such as Dakarmorphose4 or Habiter Dakar5. Most importantly, my practice of Worofila has enabled me to work with architects and engineers like Doudou Deme to define a language of bioclimatic architecture utilising raw earth and typha to make buildings that reduce the greenhouse-gas emissions of construction in a world where we are increasingly threatened by climate change exacerbated by uncontrolled rapid urbanisation with concrete, steel, and glass.

-

- Raw Material Company, Black Rock Senegal, Centre Yennenga, l’Ecole des Sables, Selebe Yoon, etc.

-

- The Trade Fair of Dakar and the Musée Senghor are a few examples.

-

- Refers to the civic center, often located under a tree around which various family compounds would be organised in traditional Lebu or Wolof settlements.

-

- Dakarmorphose is a research project centred on the architectural and urban history of the indigenous people of Dakar as an entry point to question what is the value of the built heritage of Dakar.

-

- Habiter Dakar is a research project that looks into the evolution of housing in Senegal and proposes an approach to conceptualise housing that addresses the socio-cultural, climatic and urban specificities of Dakar.

- Habiter Dakar is a research project that looks into the evolution of housing in Senegal and proposes an approach to conceptualise housing that addresses the socio-cultural, climatic and urban specificities of Dakar.

Related events

Related articles