Siej, Jri Bramon, and other plants

Pujita Guha on how Khasis build worlds in the forest

This article is part of Zomia Garden, a project curated and edited by the 2023–2024 CCA Emerging Curator Yutong Lin. In this series, Lin invites various scholars and artists to reflect on the ecology, landscape, and culture of the Himalayan-Hengduan Mountain region through an analysis of specific botanical species.

I. Siej

I was visiting Tyrna, a small forested village in the East Khasi Hills, which along with its neighbouring hamlets and towns, record the highest densities of rainfall anywhere in the world. Bordering Bangladesh, the East Khasi Hills are located in the northeastern Indian state of Meghalaya, which translates to “abode of the clouds.” Khasis, the Indigenous community who inhabit these hills, consider their elemental state of being as living in the mist.1 The landscape, carved by deep limestone gorges, consists of subtropical forests where pines and bananas often share space, in a milieu stewarded by, and under the autonomous rule of, the Khasi community.2

One late afternoon, Federick—my Khasi interlocutor—and I decided to take a walk through the more sparsely traversed trails around Tyrna. Earlier in the day, I almost lost my cool at a German backpacker who kept asking me for unknown routes in the forest. I repeatedly told him there are no empty, undiscovered lands, no terra nullius that he desperately sought, and no traces of scales and networks spanning across the Indigenous civilizations of the tropical belts of the world—suturing historical connections with Mayan and Aztec-built infrastructure. My interactions with the backpacker underscored my own relation to the forests as one of terra indigena, a place lived and attended to by the Khasi Indigenous community, whose invitation I wanted to respect as I walked these lands. Walking with Federick, I began to think how I walk “with” my Indigenous interlocutors: recognizing our companionship and friendship, talking to and attending to each other’s silences, and accounting for the fundamental differences in power and structural positions between us. Afterall, as an upper caste Bengali, I carry the baggage of my community’s cultural and economic domination of—and continued extractive relations with—Indigenous communities, and close ties to colonial forces in the region.3 Thus, Federick’s invitation to walk with me was a gift, an invitation to become a guest of the forest. Politically, it meant practicing a sense of ethical and critical settler allyship, and an orientation to researching forested life worlds in upland Asia.4

As we walked, I was intuitively drawn to noticing the trails as pristine places—bird calls and wild boar grunts echoed in the distance and the trails were overgrown with moss and mulch from the rain. However, my earlier conversation on forests and empty lands gradually pulled myself into noticing human presence in these forested trails. Federick pointed out to me how Khasi villagers had sculpted deep indentations on betel trunks to climb on their bulky stems to fetch leaves or nuts from the branches, since carrying ladders into the forest was impossible. Khasis make rungs to forage betel leaves and nuts to make Kwai, or betel nuts rolled with betel nut leaf and lime. The endless chewing and spitting of Kwai are the socially acceptable form of narcotic consumption, often the basis of any Khasi social gathering. The mild arecoline from the betel nut gives a tizz to new initiates.

-

Fileona Dhkar, “We Come from the Mist,” in We Come from the Mist, edited by Janice Pariat (New Delhi: Zubaan, 2023), pp.100–103 ↩

-

The Khasi Autonomous Councils is a Khasi-run council that has legal or administrative rule over the East and West Khasi Hills in Meghalaya. It was formed in 1952 and continues to have rule everyday presence in the region even today. ↩

-

Reeju Ray, Placing the Frontier in British North-East India Law, Custom, and Knowledge (Oxford University Press, 2023); Sanghamitra Misra, “Bengali Communities in Colonial Assam,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History (2019). ↩

-

Candace Fujikane, Mapping Abundance for a Planetary Future: Kanaka Maoli and Critical Settler Cartographies in Hawai’i (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 16. The notion of “critical settler ally” refers to a non-Indigenous researcher who is both attuned to the histories of colonial violence and to foregrounding Indigenous knowledge and ways of being in the world. ↩

Khasis forage betel leaves from the forest as a means to both earn in small village markets and derive pleasures from the forest. The rungs in the trunks make these pleasures possible. They are part of a Khasi design paradigm that recognizes the abundance of the forest, while showing humility. It is not a design or architectural practice that undertakes massive engineering, or modelling controlled environments, but tinkering with nature to allow new affordances and to flourish life amidst it. The forest is a space of everyday life for Khasis—a space of minor inscriptions, etchings, and marks that show how to live on its edges.

At a few places, Federick observed how the hardwood stumps had been gathering moss by the trailside, while the larger trunks had been taken away for making wooden huts in the forest. These stumps were also being swallowed by synsar (broom or jhadu grasses) and siej (bamboo). These are minor disturbances in the forest that allow light into the dense and tropical canopied expanse—to air the forest light, as it were. Both synsar and siej spread rapidly through these forests, especially around patches of forest clearing or secondary growth, taking over the grass along the forest’s edges. As these grasses spread rapidly, Khasis forage them. Synsar is primarily used to make brooms sold in the market. Siej is used according to its age, form, and structure: siej shrah (long, hard, tall bamboo) is used for construction; lung siej (young bamboo stock) is used for pickling and food; siej long (perfectly hollow and straight bamboo stem) is used to form irrigation pipes in the terraced hills; lighter, thin, and pliable bamboo is used for weaving. Bamboo proliferates and shapeshifts in these forests between genus and species, whose colours, forms, and leaves vary. The abundance and multiple affordances of bamboo is uncaptured in the singularity of the English descriptor for the family of grasses. Siej is ubiquitous, and Federick was building a whole world with it.

II. Jri Bramon

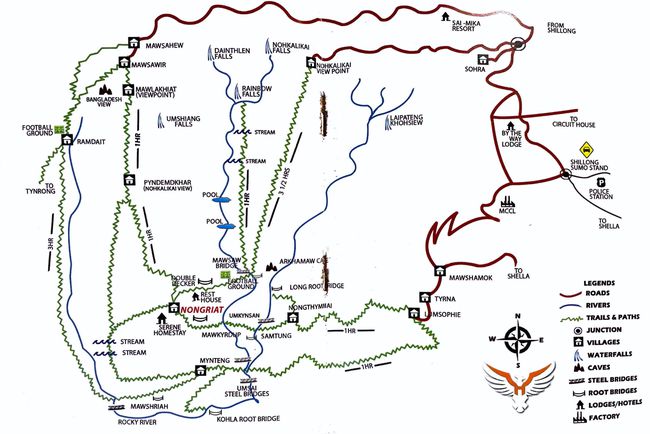

While tiny, Tyrna has recently been heavily visited by tourists, field ecologists, and state department officials, all of whom (however differently) study, walk upon, and document the living root bridges, trekking routes, and waterfalls in the area. The suspended living root bridges are built by weaving or stringing together the aerial roots of the Indian rubber plant, Ficus elastica. Khasis refer to them as Jingkieng Jri—Jingkieng for bridge and Jri Bramon for rubber. They first plant a Ficus elastica on one side or both sides of the stream. As the plant grows and roots develop, Khasis build a scaffold during the monsoons to wind and direct the roots when they are the softest and most malleable. This process is called iaki-thied, or the training of roots: a Khasi choreography of control and care with the plant. The scaffold is made up of Kwai or Siej poles that gradually weather over time, leaving the Ficus roots to become the bridge. Here, because of the heavy rain, Siej or steel bridges quickly wash away, crumble, or rust; only living root bridges grow and thrive over time in this climate.

Building the root bridges fundamentally means contending with the hilly terrain. One has to trek up and down thousands of steps along a steep hillside. Hamlets are perched higher on the ridges, and the root bridges are always at the foothill of gorges—where it is usually flat enough for the tree to take root and for Khasis to find and carry synsar or siej poles on the riverbanks. Khasis build bridges in close relation with vegetal time—allowing plants to mature thirty or forty years before they can be walked upon as functional bridges. Each bridge thrives for a century or longer.

Aparajita Majumdar notes that root bridges are a “recalcitrant” or ungovernable Indigenous typology that challenged British colonial uses of Ficus elastica. British plantation owners had sought to tame, extract, and make rubber plantations from the plant, a process that had eventually failed in the region.1 Sitting at a root bridge in Tyrna, I saw gashes on the Jri Bramon trunks too. These gashes, as Federick told me, point to a time when Khasis also tapped rubber from the trees. But once their roots were extended onto a bridge, Khasis stopped tapping them—letting the trees, as they say, live and gift longer. Khasis build worlds with gashes that heal across time, as new layers of bark that extend and close older wounds.

-

Aparajita Majumdar, “Recalcitrant Lifeworlds: Decolonizing the History of Human-Plant Relations,” Environmental Humanities, 16, 1(2024): 79–99 ↩

Over the last decade or two, Jiengking Jri have gained public and state recognition. They were recently submitted by the state of Meghalaya for a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage status. In Shillong, Meghalaya’s hilly capital, there is a plaque of the Jiengking Jri outside the state archives and a mural opposite the High Court building, each depicting the bridges in a thriving ecology of forests, tigers, Khasis, and other living beings—a tableau vivant of kinship, sustainability, and multispecies relations. This recognition for Khasis, has also threatened local ecologies; the cunning, or duality of recognition that both Aparajita Majumdar and Frederick express differently.1 Tyrna is home to the Rittymen root bridge—the longest in the world—and the Nongriat double decker root bridge, which is more than 150 years old and the iconic emblem of Meghalaya. While Rittymen is accompanied by signs or requests from local villagers not to walk across it in groups to avoid its collapse, at Nongriat Khasis have placed wooden planks on the bridge to sheath the ever-growing young roots.

The discourse of recognition is always caught in a double bind. As I keep overhearing people murmur whether this recognition is deserved or not, the homestays and cemented pathways and trails have been created on these lands to serve tourists. Meanwhile, limestone and coal mining in Meghalaya cause greater ecological harm to these forested environments. Witnessing these events of ambivalence, people ask me, what is the impact of tourist economies, on which these villages survive, in a neoliberal economy?2

Beyond binaries of harm and violence, economies and their opportunity costs, I also realize recognition disavows how local Khasi residents recollect building Jingkieng Jri. As the Khasi community moved deeper and deeper into the hills because of war, these vegetal infrastructures provided the means to cross the riverine and forested terrain. According to the oral history and genealogical recollection around Tyrna, the region came into being because of war between neighbouring villages Mawphu and Nongriat, and the larger resistance to the Sohra kingdoms. Mawphu villagers sent over bulls to plunder Nongriat, whose residents killed and ate these bulls. However, the bulls had been poisoned by Mawphu residents and the Nogriat villagers died as a result, except for one family that refused to eat the bull meat and survived, eventually spreading their clan across the Tyrna area. Fugitivity, war, and seeking refuge in the forest undergirds a local historical understanding of why they came to build root bridges in the first place, and such fugitive conditions have produced multispecies relations with the Jri Bramon tree. Contemporary state recognition thus colonizes the community’s political agency—preying and prying on their worlds by making them icons of multispecies and sustainable living—while obfuscating the political and historical conditions of refuge and refusal in the forest through which these worlds are built.

Khasi refusal or distance from the state manifests in many forms, some laced with humour. My Khasi friends and interlocutors tell me how modern steel bridges in the area, designed by civil engineers, have either collapsed, thanks to boulders or rocks flowing with the force of the stream, or rusted away in Meghalaya’s extreme humidity. On the other hand, Khasis built their living root bridges by placing them at a slight oblique angle to the stream, at bends and curves along the riverbanks to prevent the direct impact of boulders. And they were made with living roots that thrive instead of collapsing in the rain. Khasis are often amused by the state’s efforts to build bridges in the area—a mild disdain towards modern civil infrastructure. At the Mawsaw bridge, Khasis have extended roots from the adjacent Jri Bramon trees and woven them around an existing steel bridge—an attempt at recuperating a bridge that they consider as the state’s presence in the hills. While the Mawsaw bridge is closed to visitors for now, I saw how tree roots have been tucked in, woven around, and made to fill the gaps on the steel bridge. One day, this rusty steel scaffolding will chip away and the three Jri Bramon trees that envelope it will hold the bridge and those who cross over it.