How do you really transform this ground?

Carla Juaçaba on permanence and fragility

This lecture marked the opening of With an Acre. Edited excerpts of the transcription are published below.

This [Groundwork] trilogy is about ideas and dreams, but I think there is absolutely no utopia in these ideas and dreams. Everything is grounded in reality. I learned from the theatre director, Peter Brook, that in his theatre, it is the imagination of the public that fulfills the image. Nothing is entirely given. So, with the projects in these three exhibitions, you can imagine what they might become, whatever you want.

I have a problem not only with the idea of permanence in architecture, but with the idea that images will never change. In the exhibition, With an Acre, is a fragment from Camila Freitas’s film Chão (2019) where you can see Brazil from the top. I think it’s a very beautiful image, and it’s an important moment to observe the ground of Brazil from above and therefore understand its history in the present moment. Chão, which means land or ground, is about the Landless Workers Movement [MST]. MST is the most important agro-social movement today, a peaceful organization of around 400,000 families, moving around Brazil searching for land to plant. They occupy unproductive land, set up camps made of black plastic tents. Real cities that are extremely fragile and easily collapse with the wind. We also have a history of this fragility with the Indigenous nomad structures that, for other reasons, are nomads. They are nomads because they understand that they have to move so the land can be restored. The reasons are different, but the fragility is the same.

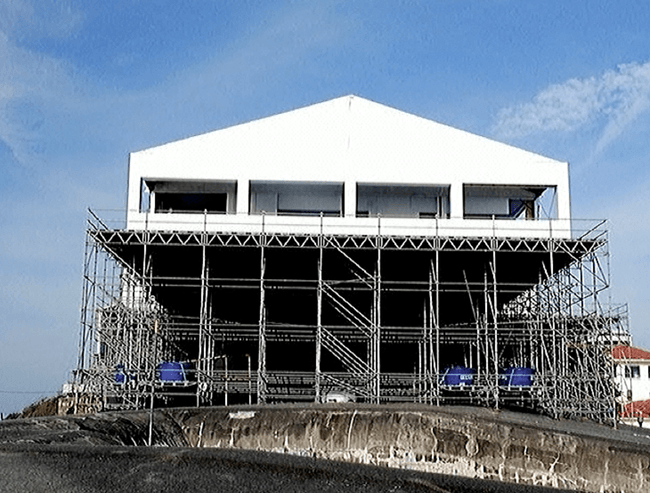

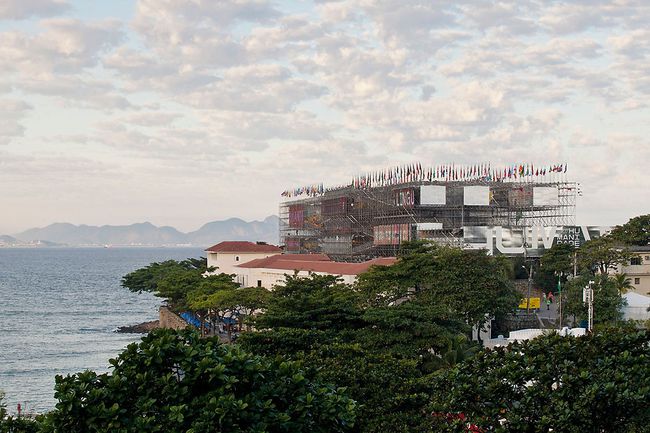

I’m going to show a project from 2012 made together with the theatre director Bia Lessa. Pavilhão Humanidade was a temporary building made with 9000m² of scaffolding for Rio+20, the International Conference of Sustainable Development. It is a design that comes from the observation of a place in the case of Copacabana, of its events. If you go to Copacabana at any time of the year, there is a scaffolding for volleyball, or for shows, or for the New Year’s Eve carnival.

I found this plastic tent with air conditioning inside, supported by continuous scaffold walls—107 metres in length and 5 metres high. At first, there was an invitation to do an exhibition about sustainability in the plastic tent. And Bia Lessa said, “I’m not doing an exhibition on sustainability in Copacabana with air conditioning.” So, she started looking for an architect.

And so, the idea was to remove the plastic tent and continue this preexisting fragile scaffold structure 25 metres high. The programs give stability to the walls. There are auditoriums, a small one looking to the sea, and this big one for the events separating the public, because it is for the United Nations. So, there were entrances for the United Nations and entrances for the public. It was visited by 200,000 people in 15 days. There was queue of 1 kilometre, but for everything in Copacabana, there’s a kilometre queue—just because its free.

When this building was dismantled, there was absolutely no trace of it in the ground. And the material has been and will be reused in other buildings.

This is a scaffolding building, but it’s for people. There was a crisis in the middle of the construction process, wondering if this was really going to stand up with so many people inside. And the answer of the engineer was very funny. He said, “it has 7000 base points. It will work.” So, they continued.

It was constructed in four months. The comments of the public were very funny. In Copacabana on the television, people were debating “Is this a green building? No, it is not a green building.” And then another woman said, “Everything is very beautiful, but when are they going to remove the scaffolding?” So, the opinions were very, very different.

This is the Vatican Chapel, made in 2018. The curator, Francesco dal Co, invited ten architects to design temporary chapels [for La Biennale di Venezia] on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, which are not temporary anymore. They are part of the Italian heritage. Francesco sent me an email, and I didn’t respond because I thought it was spam. We wanted to do a chapel in Venice, but I didn’t answer because I didn’t know him. Then after some days and he wrote back again asking, “but are you not going to answer this?”

I couldn’t go to the site, and he sent a video to explain it, and I thought it was very beautiful—the level of abstraction, this light that comes and goes, and this feeling of Venice behind these trees. It was very nice.

The foundation is only 12 centimetres deep and it is held under the ground with pieces of concrete just landed there. It has two crosses: the cross down is a bench, the standing cross is the cross. It has a very a synthetic program, a very old program. You go to the chapel and sit and look at the cross.

There was this question all the time: this is not architecture, this is a sculpture, this is an installation. And I said no, this is architecture because it has a program. You go there and you sit and look at the cross. It is architecture. And [Eduardo] Souto de Moura resolved this problem for me, he said, “of course this is not a sculpture who sits in a sculpture?”

A few years before this, I did an installation, and I find a very abstract relation between this object and the chapel. But it’s very abstract. It’s just lines floating in the in the air. It’s brass beams, 1 by 1 centimetre. And with this installation, I observed that this thin line could really be a drawing in the space. It is suspended by the force of the magnets. Nothing is glued. Everything is suspended by this force. And there’s one only point of equilibrium. There is an apparent and tranquility in this object. But there’s a high level of entropy. And this effort is never seen in architecture—this entropy. But in this case, there was an earthquake, and everything collapsed and broke down in the floor. So, isostatic is not for Mexico. I make this visual association with the chapel, but with a certain distance.

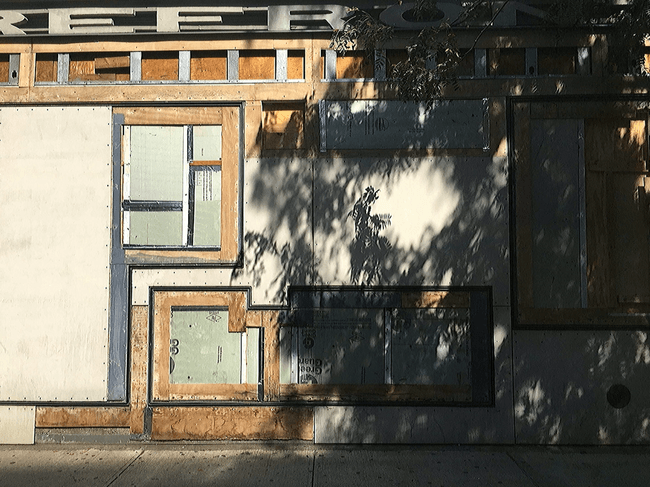

This is the Storefront for Art and Architecture. And as you know, everything in New York is too much. The first thing I thought with this invitation was to undress this iconic façade and remove it. But I didn’t know I was going to find a favela underneath. I didn’t know I was going to find this. I thought it was going to be like Swiss construction inside, but it’s not. It was so beautiful to discover. I think they had a lot of fun to do this.

The idea was to undress the façade and do an installation with the elements of the facade inside. I did this, this gesture of undressing. And the other artist came and took the pieces and made it flow inside the galleries. José Esparza Chong Cuy [Director and Chief Curator] wanted to return to the origin of the gallery, which is art and architecture without “highlighting” the artists. We didn’t talk to each other. There was no talking between the artist and me. I removed the façade, and he did the inside. It was very interesting because it was just about elements that come from the façade to the inside and then return to the facade. There was absolutely no material besides what is there. Marcelo Cidade from Sao Paulo, was the artist.

I will show a couple of houses because this is part of my life, I have a couple of house projects going on now. I have never designed a house that exceeded 140 square metres, which is not common for the bourgeois life of Brazil—it really exceeds this. And I think my designs are not for clients that really have problems of a budget, but it is more about finding what is necessary for life.

This is the second house I did. Very cheap. It was very cheap. This is very raw. There’s no, you know, layers of anything. And this light that travels during the day in this forest is absolutely beautiful. And there is a metre and a half of projected roof [overhang] to open the windows when it rains.

I think one of the wonderful things in the Atlantic Forest is to feel, to smell. And I remember now in my house growing up, when it’s raining, you run. You run to close the windows. And I said, no, I’m going to do houses where you open the windows when there’s heavy rain and so you can enjoy this. It’s great.

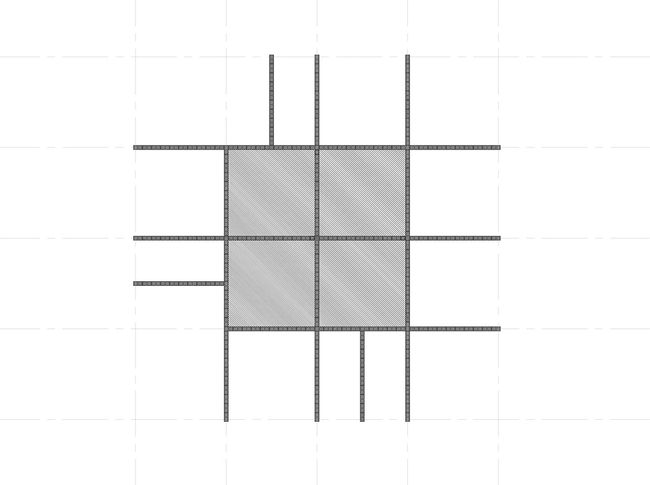

This is the Posse house. This drawing is not a drawing of the house, but it’s the drawing of the foundation. The soil is hard, so I didn’t need a foundation, instead we just had to find level ground. And the foundation is a drawing, but the foundations are also the walls, and the foundations are the structure. This drawing shows this idea of these transformations of ground. It is a design. Our very first design should be how we transform the ground. I think there is a gesture there. This house has been under construction for many years. It stopped, but now they are returning to finish the construction.

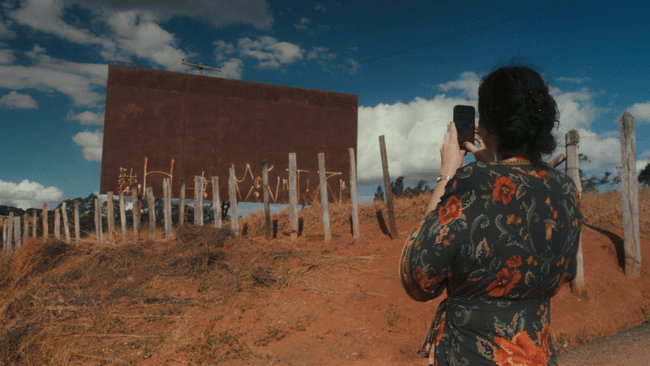

And now, I’m going to talk about Flor de Café. This is the view from this structure that we are proposing. In our trip to film With an Acre, I photographed this billboard, which was an inspiration because they’re very fragile, uh, they’re the only vertical element in the landscape, the only viewed element on the landscape. The billboard was the beginning of the idea for the project, both sides not to inhabit. It’s made of eucalyptus, which is in the forest and very easy to have. The idea with this design was to do a very inexpensive building, and the detailing process was about removing complexity, not to adding complexity. That means to make it as simple as possible—to have less actions. If you complicate it, or if you design beautiful junctions of wood, that means work, that means added budget, that means energy. I think we have to think about actions when we draw—a drawing is an action. It’s not an abstraction.

I’m using the reference of the Shabano, the Yanomami houses. The geometry of the Flor de Café is inspired by this both idea of the empty centre and the geometry. As it is shown in the exhibition, we took a very long time to find the dimensions of this project, because it’s really a million dreams. I didn’t find the dimensions Milena Rodrigues [the client] wants. She wants an auditorium. She wants also people to go there and sleep. And then it becomes a huge thing. And I said let’s do something smaller, more feasible, and inexpensive. And then if you want, you can continue with these models in another part.

So again, the thing is to elevate so the ground is free, as all the grounds are free in Brazilian architecture. If you remember MASP [Museu de Arte de São Paulo] by Lina [Bo Bardi], you remember the ground of MASP is open—from the playground to a public manifestation to a carnival, or whatever. So, we understand ground as a free space. And this is part of our Brazilian culture for sure. This ground, [of Flor de Café] is also free, we can imagine. With no set program, there’s nothing happening, so we can imagine many workshops on the ground for children, we can imagine an outdoor cinema screen inside this courtyard. We can imagine what life brings to this space.

Also, if you remember the architecture school designed by Vilanova Artigas in the University of Sao Paulo… I don’t know if I’ve ever been to another building with no doors. We enter from inside. It’s really this free ground. And that’s what we want in this project.

I’m going to finish with a quote from the philosopher and Indigenous leader, Ailton Krenak: “step gently on the ground.” And I always imagined this sentence, in architecture, is about how this ground, and how the foundation is the first intervention. How do you really transform this ground, this territory, as a first concern in design? It’s open to imagination, but I like this sentence, I think it’s very beautiful.