Circular Time

Excerpts from Amanda Licker’s installation, Everlasting

The text and images below are excerpted from an installation conceived by Amanda Lickers in the Shaughnessy House to accompany the projection of her film, Everlasting. Multidisciplinary Haudenosaunee artist Iako’tsi:rareh Amanda Lickers is the CCA’s 2023-2024 Indigenous Land Restitution Research Creation Fellow. The call for the 2026–2027 edition of the fellowship is open until 23 November.

In Indigenous worldviews, time is conceived as circular and non-linear. It includes dynamic systems that are interconnected and interdependent with the natural world. The notion of deep time integrates Indigenous knowledge systems with geological, sociocultural, and relational perspectives, encompassing all relations—human and nonhuman, place and seasonality.

Land-based practice refers to relational, embodied, and place-specific ways of engaging with land that move beyond seeing it as property or resource. Here, land is understood as a living relative, a teacher, and a source of knowledge, where relationships, responsibilities, and understandings are continually formed and renewed.

Unlike placemaking, the practice of placekeeping is anchored in continuity and emphasizes Indigenous care and stewardship of the land. It nurtures existing ecological relationships, deepens understanding of cultural and ecological narratives, honours ancestral knowledge, and ensures that development sustains rather than displaces Indigenous presence.

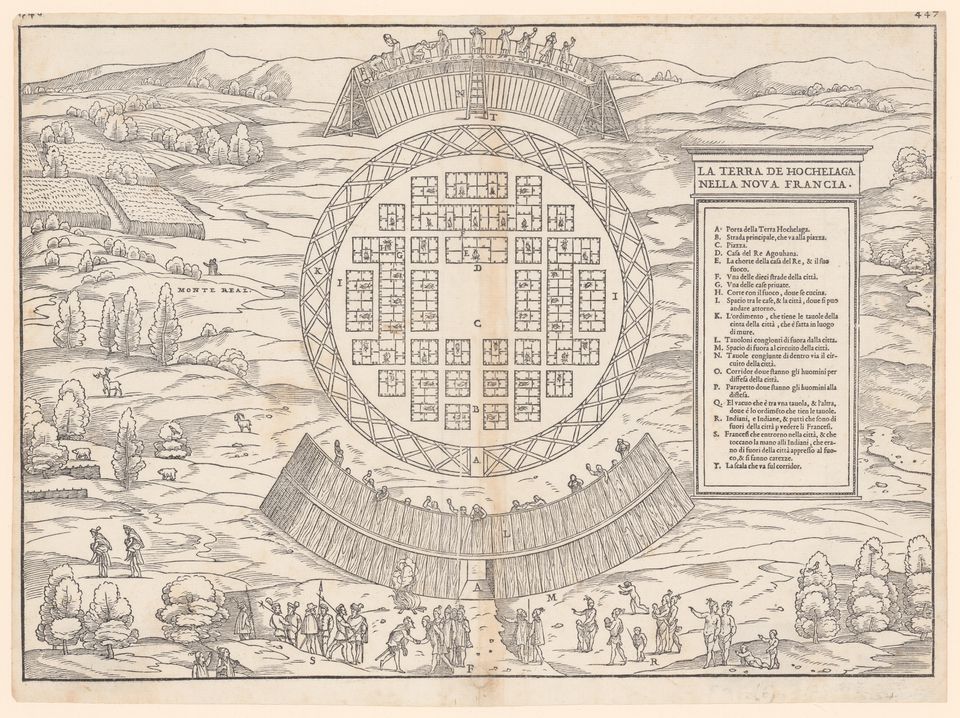

Attributed to Giocomo de Gastaldi, Venice, 1556. La Terra De Hochelaga Nella Nova Francia [The Land of Hochelaga in New France]. This map, drawn from Jacques Cartier’s writings as he arrived on the mainland, reflects Renaissance sensibilities and the settler gaze in depicting Haudenosaunee communities. The print perpetuates incorrect placenames and orientalist perspectives of Onkwehón:we. DR1986:0441, CCA

The Latin phrase terra nullius can be translated as “land belonging to no one.” Originating from Roman law and the 1493 papal bull Inter caetera, it was later integrated into European legal and colonial discourse. The concept became particularly significant in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, alongside the Doctrine of Discovery, as a moral, legal, and spiritual justification for European colonial powers to acquire lands deemed “empty” or “unoccupied.”

This framing casts non-Christian Indigenous peoples globally as subhuman enabling and normalizing slavery and land theft. Within two centuries, supposedly “empty” lands had already been granted to Western landowners, some of whose names remain attached to urban areas today. While the Vatican repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery under Pope Francis in 2023, its legacy still lingers in Canadian law.

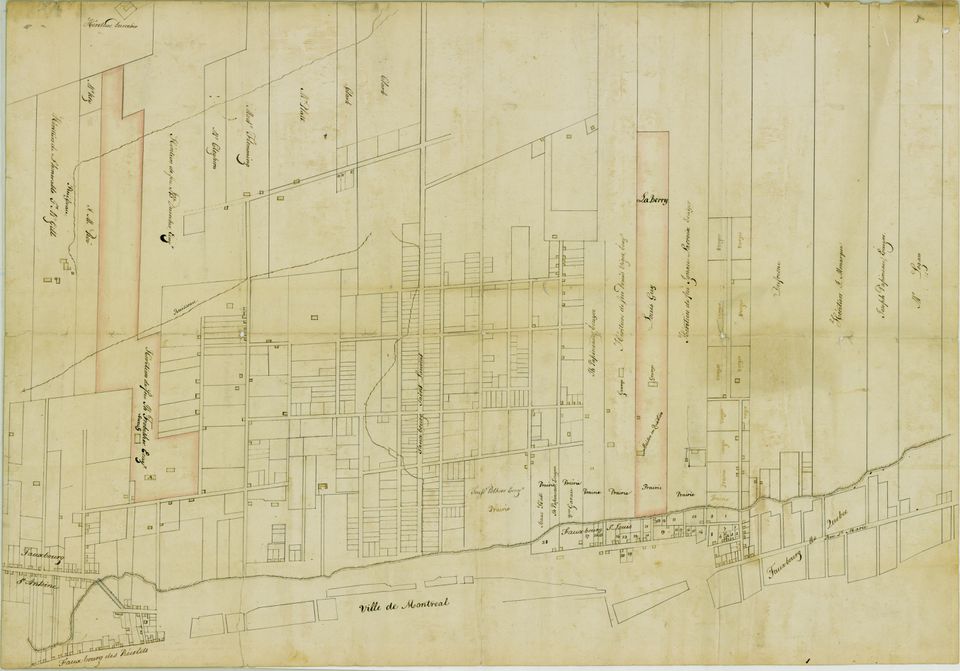

Map of the City of Montréal c. 1815 showing the location of the largest properties and names of the landowners. This map, showing square parcels of land, illustrates the colonial legacy of land dispossession. Highlighted are the lots of Joseph Frobisher, founding member of the fur trading syndicate, the North West Company and Chairman of the Beaver Hall Club, an exclusive dining hall for fur barons. The Beaver Hall Club was celebrated as the pinnacle of high society and served as an old boys’ club, featuring prominent figures such as James McGill. P318,S8,P32, Bibliothèque des Archives nationales du Québec

Narrative sovereignty designates self-determination of cultural depiction, storytelling and meaning-making. It shifts the power to represent from outsiders back to Indigenous and marginalized communities, who reclaim the ability to shape, share, and protect their own stories in ways that reflect community values, worldviews, and political goals. Storytelling, as a method of sustaining culture, memory, law, and identity across generations, also challenges dominant narratives that silence, distort, or commodify Indigenous voices and knowledge.