Line of Flight

Kitty Scott offers a reading of the Gordon Matta-Clark collection

When I decided to focus Line of Flight on Gordon Matta-Clark’s travel photographs, I had never seen any of the material before, so my entry into the archive was quite a cold one, so to speak. The first time I came to see the photographs, the boxes and binders were all laid out on a table in the study room and there was a huge volume of material. The experience was immediately overwhelming. The collection of analogue material is diverse and includes slides, transparencies, negatives, and prints, but other than the prints it was quite difficult to see anything in great detail. I started out by looking in a way that was, I would say, very much on the surface of the images. Slowly, my eyes adjusted, but it took some time. The CCA started scanning entire sheets of slides and negatives, and it was then that I was able to really begin to look at the images, enlarging them on the screen. I discovered you could spend hours and hours researching a single image. The exhibition consists of a selection of about four hundred images (a fraction of the entire collection) and they are projected at such a scale that I feel as though I’m seeing them for the first time. Of course, I have been looking at them for a long time, but I certainly know more about them now than when I first selected some of them. There is value in seeing through Matta-Clark’s eyes, through his camera, and making his photographs large enough to create an immersive experience opens up that possibility.

Matta-Clark had a cosmopolitan upbringing—moving between places like New York, Chile, and Paris—and dual South American and American heritage, which meant that he looked at the world through a particular lens. While searching through one of the boxes, I came across his passport, a marker of his identity and the document that permitted him the privilege to travel. It was a different time, of course, but he was still a very privileged person in that he could move with relative freedom around the world. The notion of an artist frequently embarking on international travel was new at the time. Passenger air travel had become cheaper and more accessible in the 1970s and Matta-Clark went to a wide variety of places in a relatively short period of time. The images in this exhibition were taken over seven years, from 1971 to 1978, during numerous trips across North, Central, and South America and Western Europe. Often these trips were leisurely, but sometimes they were for projects, however I have not distinguished one from the other, as I am not sure how useful such an exercise would be. There is a beautiful set of slides Matta-Clark takes when he is travelling to Paris and all he does is photograph the wing of the plane from his window as the daylight changes. In a way, these are the typical pictures of a tourist, but they are also those of somebody observing the world in a very specific way.

At the beginning of my research, I was only interested in the slides and wanted to digitize and show all of them, but I began to ask myself how we could know if Matta-Clark had actually wanted to shoot with slide film so much of the time. This was a period when slide and camera film were sold at drugstores and small shops and often you might have gone in looking for print film, only to find that they only had slide film, or you might have wanted slide film and all they had was print, or black-and-white, or colour. I am sure that the diversity of formats Matta-Clark used was a matter of chance. What is interesting about the slides, in particular, is that their date, year, and number markings can tell you something about the sequence in which the photographs were shot, and when they were taken or developed. In thinking about making an exhibition, it became clear that rather than selecting one or two slides I might want to select a whole sheet or an entire roll of film, in order to be able to look at how Matta-Clark photographs, to be able to follow him through one place and then another as he travels. Within a sheet of slides, you often get the sense of him coming across something that catches his eye and then he’ll photograph it from a number of different angles, which I think of as similar to how an architect might take notes to document a site. Matta-Clark doesn’t just arrive at a place, he moves around it and he finds his pictures. So, to some degree, I think of a series of slides as his artist notes.

I also found photographs of Matta-Clark taken by other people; images seen through the eyes of those who were looking at him as he was travelling or immersed in a location other than New York City. In one picture, probably taken in Peru, he is standing in front of a street vendor with his little bag over his shoulder and holding his film camera; in another, probably connected to a series of slides taken while he climbs up the Pacaya volcano in Guatemala, he is reclining on the sand, shirtless, wearing suede boots; in yet another sequence of images, he is lounging around a pool in Los Angeles, and surrounded by flowers. Looking at these images of Matta-Clark, I began to think about him as a multifaceted figure: not just an artist, but also a lover, a friend, and an explorer.

As I studied the hundreds of photographs Matta-Clark took, I started to notice patterns in what he chose to focus on. When he goes to Machu Picchu, for example, he looks very closely—intently even—at a wall of very carefully numbered rocks. Or in Guatemala City, he watches a fiesta move through the streets, a very colourful religious procession full of crosses and images of the Virgin Mary. Or in markets in various places, he studies people working as well as food and animals being prepared, cooked, and consumed or sold. So, I started to think of Matta-Clark’s way of looking as not only that of a tourist and an artist, but also as that of an ethnographer interested in street life and collectivity, or even that of a choreographer observing the activities and rituals in the city and the movement of bodies, or possibly that of an archaeologist studying and cataloguing ruins.

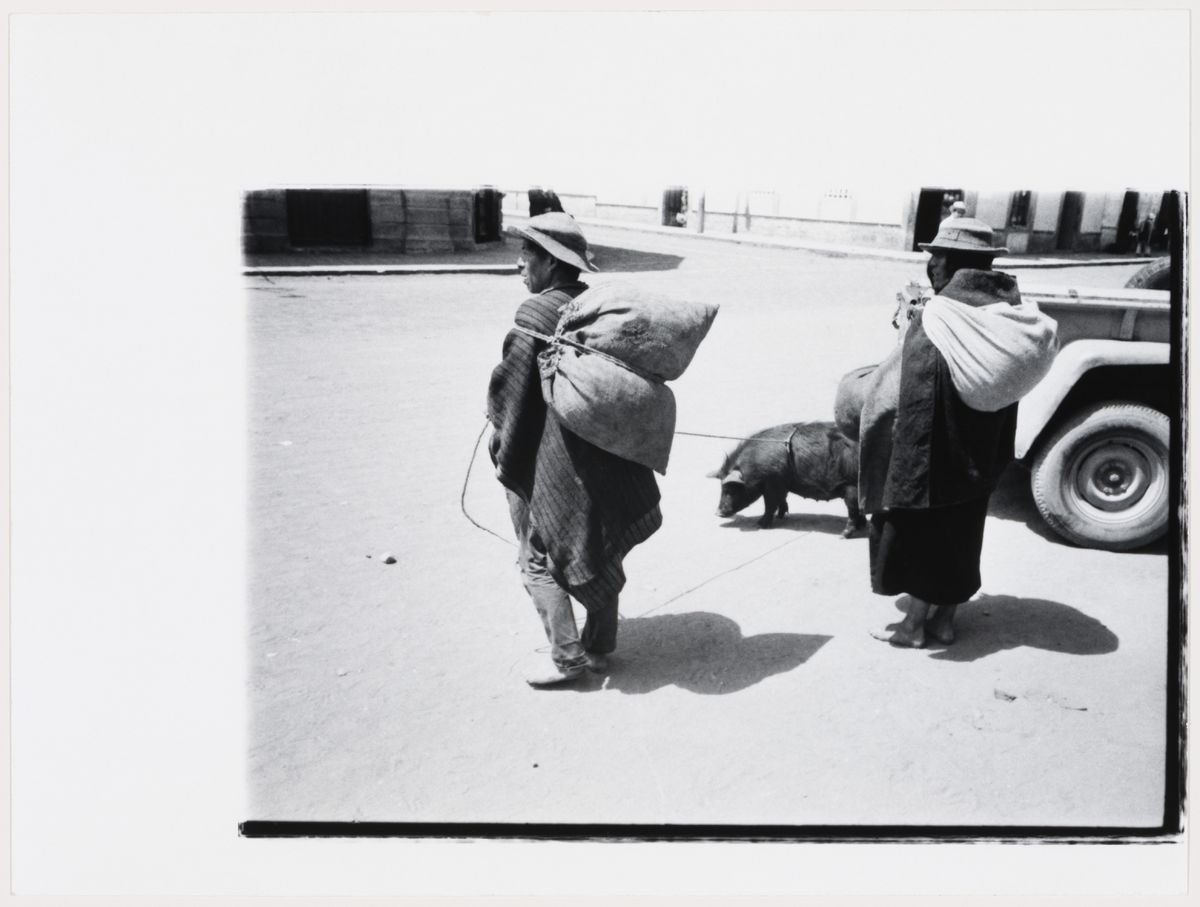

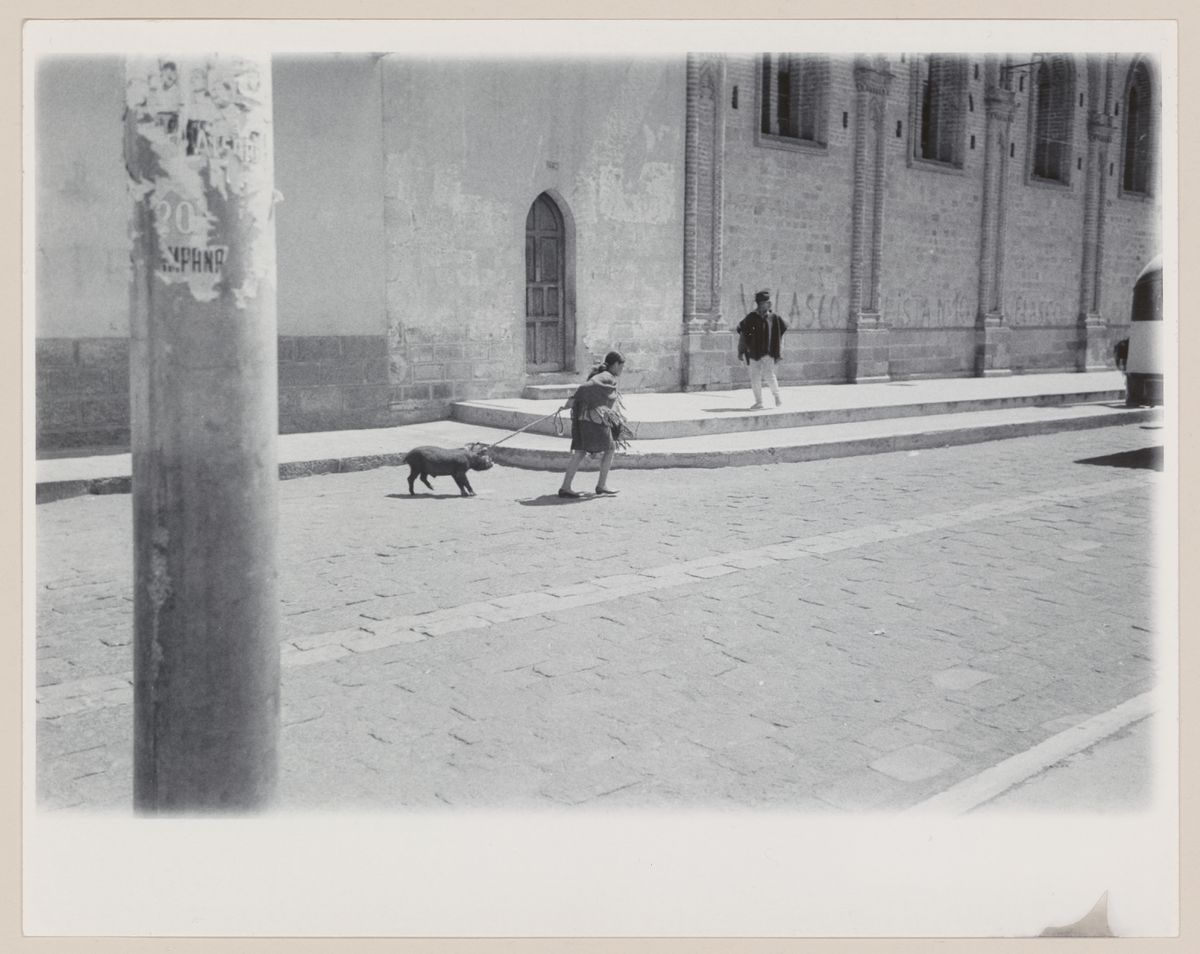

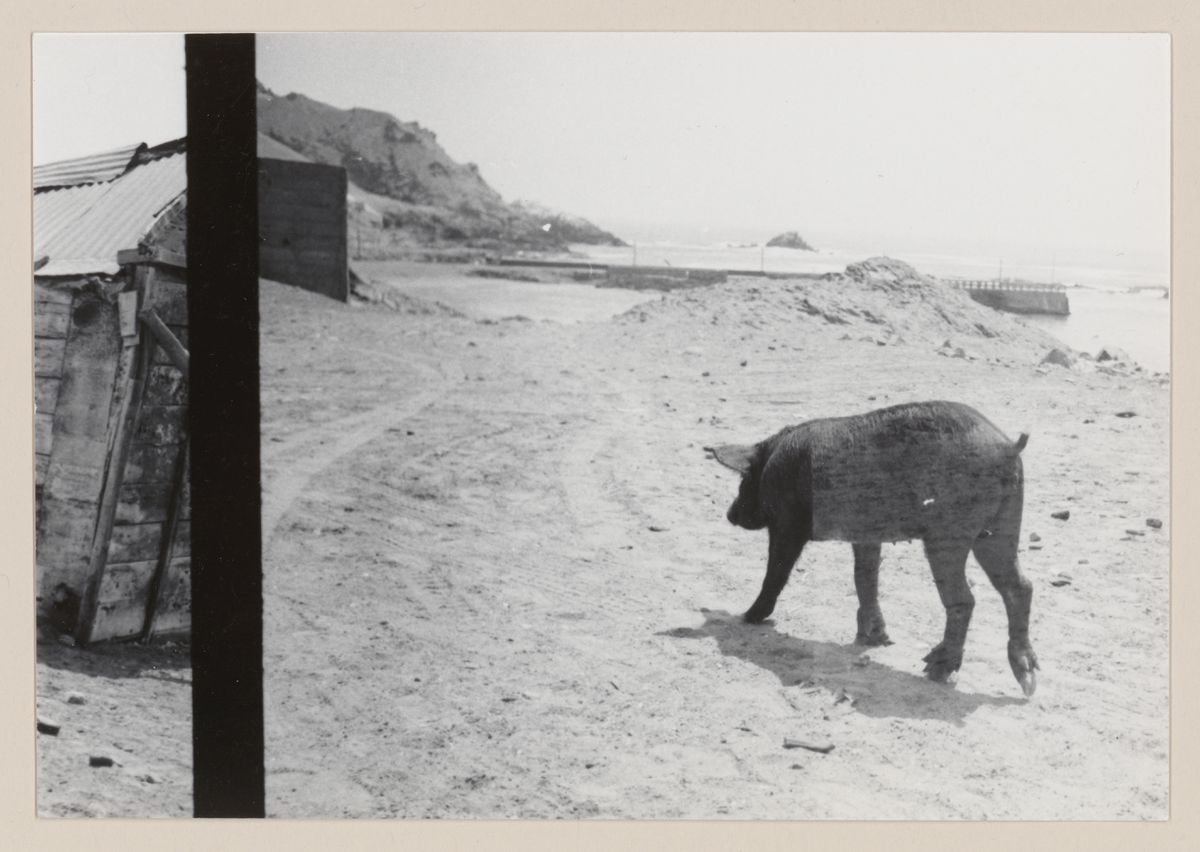

It is easy to see how Matta-Clark was very interested in cultural experiences that were quite different from his own. As much as he was involved in some of the most important living culture and art-making of his time in the United States and Western Europe, he was also someone who would stop to take a picture of, for example, a young girl dragging her pig through the streets, most likely somewhere in Chile. He is observing a basic socioeconomic condition, embodied here in a human-animal relationship, and probably wonders if that pig is a pet, or whether that pig is being brought to market, or maybe the pig has been acquired at the market. He also watches people in the city, as they go about their daily lives. In Haiti, he takes a whole series of photographs of people carrying things, like groups of women and girls with huge baskets on their heads or an individual carrying a chair in such a way that it seems as if body and chair are one. These quite banal subjects reoccur in his photographs, so it seems that he was fascinated by an everydayness, but one that looked different than the one he knew in New York.

When I thought about the way Matta-Clark worked—that every time he visited a city he would look for building sites to transform—I started to see his photographs in a particular light. For example, in one black-and-white image from Machu Picchu, he looks through a doorway to the landscape, the clouds, and the horizon beyond. And then I realized that this notion of cutting, of looking through space, of framing another spatial realm, all fundamental to his building transformations, is a repeated point of view in his photographs. In a set of colour transparencies, taken as he wanders around the countryside near Genoa, he looks at ruins, presumably Roman, and there’s one beautiful sequence in which he finds a fragment of a wall with a circular hole in it and photographs through that wall to the landscape behind, and in a second shot the view through this circular hole changes to show a church in the distance. In another series of colour slides from Chichén Itzá, he looks up at a rock face with a hole cut into it, then he approaches that hole from an internal passage such that you see the light penetrating, then he looks through that hole to a temple peeking out above the tree tops in the distance.

Another correlation that I drew between Matta-Clark’s travels and his work is his interest in ruins, both ancient and contemporary, and how these may have influenced the kinds of sites he chose for his projects in urban areas. There is an extensive set of negatives from a trip to Miami, predominantly of an apartment building in ruins, perhaps abandoned by speculative developers or damaged by hurricanes. He explores the building from bottom to top, photographing the barren structure, debris and traces of wallpaper, and weeds growing through windows. Another contemporary ruin that clearly fascinates him is a freeway in Los Angeles that has been destroyed by an earthquake. He takes a whole sheet of slides of this superstructure, this freeway cracking and breaking along a cliff, and it seems that he is studying it as he does the archaeological sites he visits. These photographs live in the collection alongside those of ancient civilizations like the Inca or Maya. In Arizona, Matta-Clark visits Canyon de Chelly where the Pueblo, Hopi, and Navajo people lived for over four-thousand years, harvesting vegetables and food at the bottom of the canyon. On the same trip, in 1976, he visits Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, and photographs the intense play of light and shadow created by openings in high stone walls and cast down into circular cisterns—images that bring to mind Day’s End, completed the year before.

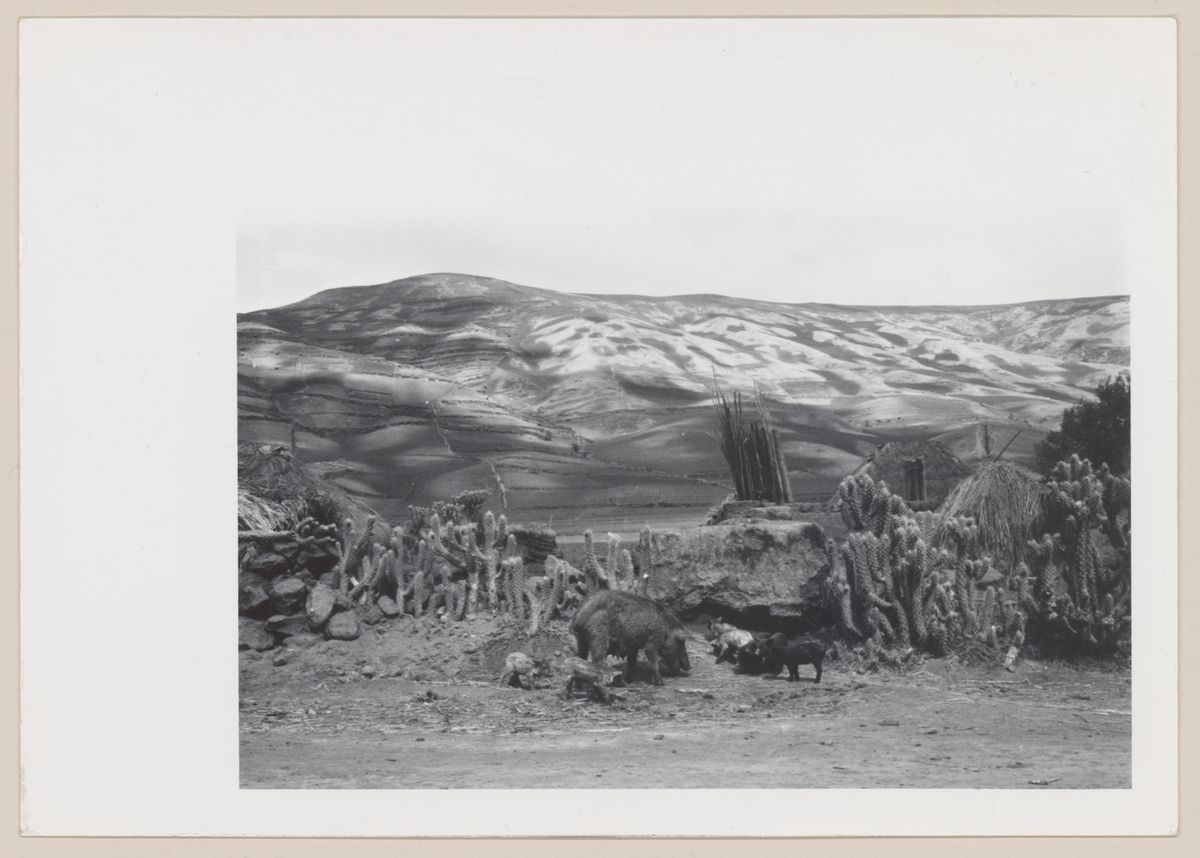

There are many other interests that emerge when looking at Matta-Clark’s photographs in their entirety, but I will just name a few. Almost everywhere he travels, he seems to stop at a graveyard site. Maybe he comes across them randomly, maybe he seeks them out. Architects are often interested in graveyards, in the sense that they are mirror images of the city and always places of human habitation. Matta-Clark also seems to photograph animals wherever he goes. In southern Guatemala, presumably near Santiago Atitlán, he takes many, many photographs of furry pigs, goats, cows, and donkeys at what seems to be a livestock market. At Machu Picchu he photographs a llama as if it’s posing for the camera. The picture is humorous in that the llama mirrors Matta-Clark, as it too seems to be taking in all that the site has to offer. But he also photographs animals as they are being prepared for human consumption—one particular series shows skinned pigs and racks of meat at a South American market in 1971, perhaps influential for his 1972 event Matta Bones. Matta-Clark also often photographs modes of transportation and his view as he is transported—by plane, train, car, truck, or bus—so that you feel a sense of temporality in the images and the frame of the window that’s just outside the frame of the camera lens. Sometimes the window view is privileged, as in a series of photographs he takes from a tap-tap truck in Port-au-Prince in 1972, in which you see slivers of bustling street life—I wonder if these images might have inspired the film City Slivers, several years later.

What exhibiting these photographs does is make visible the kind of lenses through which Matta-Clark looked at what was happening around him and the breadth of references that might have inspired his projects. It also reveals his seemingly perpetual impulse to go out into the world to know other things, which suggests that he was looking for an escape from his own existence in New York City. Matta-Clark belonged to a emerging generation of artists who, similarly, sought to escape institutions—I think of Walter de Maria and his 1977 work The Lightning Field in New Mexico, or Michael Heizer and his 1969 piece Double Negative in Nevada, or Robert Smithson and his 1969 work Spiral Jetty in the Utah desert or his 1972 lecture “Hotel Palenque.” Unlike these examples, I regard Matta-Clark’s travel photographs as documents not artworks, but behind his images, nonetheless, lies the same tendency: the intuition to work in spaces beyond those that he knew and beyond the bounds of the institution. What’s important in my perspective about the process of developing this exhibition is that it is an experiment in looking at an archive, a demonstration of what happens when you dig deep into a volume of material without a preconceived schema. I let the images guide me, and as a visually driven project I feel that it opens up a space for the archive itself to speak.