Laboratories of the Future

Robert J. Kett introduces countercultural visions for Alcatraz during the occupation of the island by Indigenous activists

I would like to begin by acknowledging that this text was written and published on unceded territory of the Ohlone People and the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation, respectively. Ongoing struggles to protect the lives, knowledge, and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples today offer a constant reminder of the continued urgency of the critiques and alternatives put forward by activists in the 1960s and 1970s.

A tape from the archives of the San Francisco alternative media collective Video Free America opens in a haze. Amid a cloud of visual static, indistinct sounds of drums, chanting, and incidental conversation emerge, only to be abruptly displaced by electronic droning. The picture sharpens, revealing figures in a dark room clustered around a bank of technical equipment. A long-haired man at the centre of the scene sits at a keyboard and plays freely on a synthesizer, accompanied by psychedelic visualizations on an array of nearby screens. The collective discusses their tools and multimedia experiments, expressing their dream of designing a unified experience of tone, rhythm, and image. “It’s really a shame that attentions to what’s going on in the world are so scattered; that a good, strong input can’t be made into the lives of the people,” the player notes.

This improvisatory session is interrupted moments later. The tape makes a rippling transition to a scene at the edge of the San Francisco Bay, where dancers in regalia perform for a dense crowd to the sounds of other drums. For several minutes, the tape holds these two worlds in tension, its reuse creating an unintentional dialogue between the technical experiments in the studio and the activity on the shore.

The confusion created by this overwriting eventually ends as the video settles on a performance by Cree singer Buffy SainteMarie. As her set comes to a close, she addresses the audience directly: “It’s getting too late and we can’t wait anymore. You’re here today to witness a takeover. We’ve taken over over there. That does belong to us and you guys didn’t tell us it belonged to us. We did the research. We found out. We did it. And here we are.”1

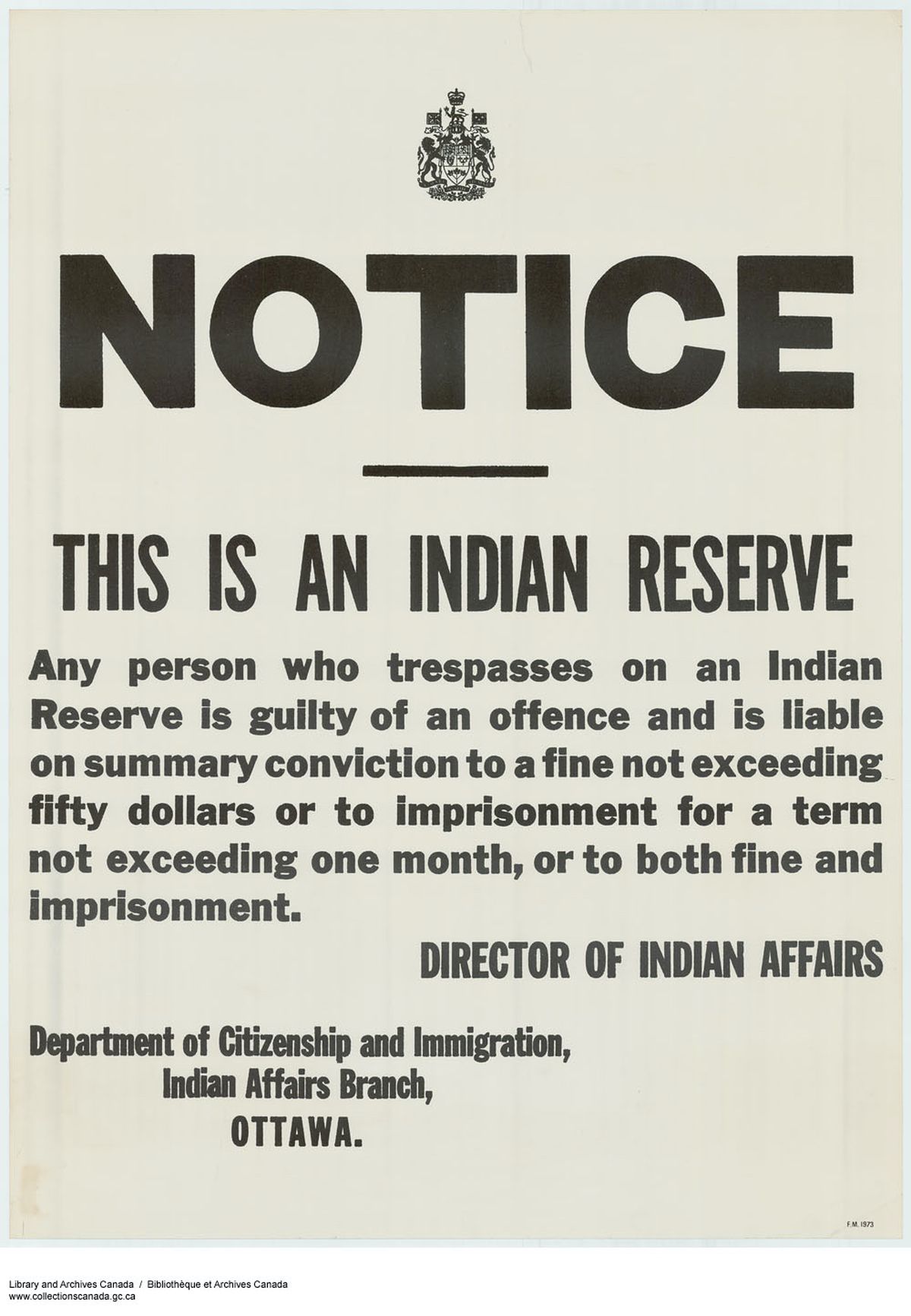

The takeover Sainte-Marie refers to is the nineteen-month occupation of Alcatraz Island, from November 1969 to June 1971, by a group of Indigenous activists from varied affiliations gathered under the name Indians of All Tribes.2 The Occupation is the most well-known of a series of actions in the 1960s and 1970s that brought the histories and futures of the Indigenous peoples of North America to broad public attention. The Red Power movement was a grassroots, youth-led response to decades of concerted neglect and aggression: through policies of forced education, relocation, and tribal termination, governments in the United States and Canada had long pursued the cultural and political destruction of Indigenous communities.3 Red Power’s project was not simply to call for recognition of these histories, but to articulate new aspirations for Indigenous life across tribal affiliations and urban/reservation divides.

My intention here is not to speak for the Occupation or Red Power, substantive accounts of which have been offered by scholars and from within the movements themselves.4 Instead, this research considers the tensions evoked by Video Free America’s accidental artifact: the intersections and contradictions between the futures offered within experimental design of the countercultural era and the claims of Indigenous activisms, claims made manifest through a range of spatial and media practices. Revisiting this history not only illustrates the cultural anxieties and desires that inspired these experiments in design and life, but also outlines an early chapter in struggles over difference, sovereignty, and decolonization in design with relevance to ongoing debates today.

Although the tape seems an unlikely archival trace, the questions it raises concerning indigeneity, design, and collective futures were widely current in the 1960s and 70s. Activist projects like the Occupation took place alongside the broad appropriation of Indigenous practices and forms within the counterculture and beyond. Conflating these cultural imaginaries and projects of indigenous resurgence, Life magazine dubiously announced the “Return of the Red Man” in 1967.5

-

Video Free America, “[Video Free America videotape. Moog Vidium feedback; Buffy SainteMarie concert]” (1970), 63 min. ↩

-

The Occupation of Alcatraz and the Red Power movement at large involved the efforts of individuals from many backgrounds and tribal affiliations. While acknowledging the fraught politics of naming—especially in North American contexts—I have used the term “Indigenous” throughout this text, one of many imperfect means of referring to the various founding peoples of the Americas and redefined as such through the shared expe rience of colonialism. ↩

-

For period accounts of the rise of Red Power and the impacts of govern ment policies on Indigenous communities, see Harold Cardinal, The Unjust Society: The Tragedy of Canada’s Indians (Edmonton: M.G. Hurtig, 1969); Vine Deloria Jr., Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1969); and Stan Steiner, The New Indians (New York: Harper & Row, 1968). ↩

-

For example, see Kent Blansett, A Journey to Freedom: Richard Oakes, Alcatraz, and the Red Power Movement (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018); Paul Chaat Smith and Robert Allen Warrior, Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee (New York: New Press, 1997); Adam Fortunate Eagle and Ilka Hartmann, Alcatraz! Alcatraz!: The Indian Occupation of 1969–1971 (Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 1992); and Troy R. Johnson, The Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Indian Self-Determination and the Rise of Indian Activism (Champaign: Universityof Illinois Press, 1996). ↩

-

For historical accounts of the appropriation of Indigenous imagery and cultural practices in this period, see Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998); Shari M. Huhndorf, Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001); and Mark Watson, “The Countercultural ‘Indian’: Visualizing Retribalization at the Human BeIn,” in West of Center: Art and the Counterculture Experiment in America, 1965–1977, ed. Elissa Auther and Adam Lerner (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). ↩

Informing both these spectacular actions and symbolic appropriations were anxieties about fundamental transformations to collective life at the time, driven by technological change and a sense of social dissolution. While Indigenous communities had been purposefully fragmented through colonial genocide and government-sanctioned policies, settler society itself felt threatened—by the generational rifts made manifest by the wars of Cold War imperialism; the so-called “factionalization” produced as marginalized communities became empowered through movements such as Black Power and the Chicano Movement; and the challenges posed by new media technologies to traditional forms of communication and community.1

Media theorist Marshall McLuhan was early in diagnosing this cultural condition. His argument positioning communications technologies as the primary impetus for social change framed a series of sweeping readings of the dynamics underpinning contemporary social upheaval. Central to McLuhan’s criticism was what he perceived as the dissolution of a modern culture of literacy and the book through the rise of electronic media of mass communication. He credited these developments with the displacement of the individualized, regimented world of print by one characterized by sensory overload, immediacy of communication, and a new sense of connectedness within and among communities.

-

For period diagnoses of this broad perception of social crisis, see Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society (1964; repr., London: Routledge, 2002); and Theodore Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture (Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1969). ↩

McLuhan gathered these reconfigurations under what he described as an ongoing social “retribalization,” a process carried out “by the simultaneous, by the electronic, which tends to put us in a kind of auditory world, or field, of simultaneous sound in which the Intuitive Man takes precedence over the Analytic Man.”1 McLuhan’s displacement of Analytic Man was echoed in the counterculture’s critique of the Cold War technocrat and retreat from mainstream lifestyles. His reading also anticipated the prominence of experiments in design and media in articulating alternatives to these lifestyles. “[E]lectro-magnetic discoveries have recreated the simultaneous ‘field’ in all human affairs so that the human family now exists under conditions of a ‘global village.’ We live in a single constricted space resonant with tribal drums,” he argued.2 McLuhan’s thinking offered a convenient narrative for framing the disruptions of the 1960s and 1970s, glossing them as a collective unlearning of modernity simultaneously premised on the articulation of post-modern futures and a supposed return to “tribal” forms of social life.

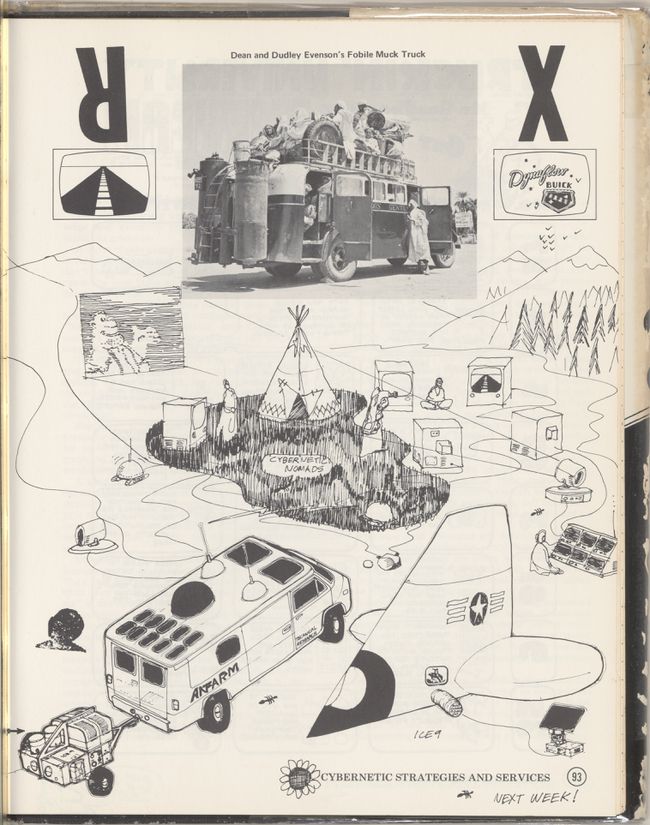

This thinking proved influential among young practitioners in the counterculture and allied movements exploring new approaches to design and multimedia. Video Free America was one of a network of underground media collectives that sought to develop creative methods “indigenous” to emerging technologies and in service to new forms of social life. These largely white, male groups drew heavily from Indigenous cultural imaginaries, adopting names like Raindance, Ghost Dance, and Global Village for their organizations and circulating shared visions for a future characterized by media “nomadism” in publications like Radical Software and Guerrilla Television. These appropriations were a rhetorical conceit that underscored the role of experiments in design and media in the creation of McLuhan’s “global village,” a world in which conflicts would be mitigated by the unifying powers of electronic communication.3

-

MMarshall McLuhan to Edward S. Morgan, 16 May 1959, in Letters of Marshall McLuhan, ed. Matie Molinaro, Corinne McLuhan, and William Toye (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 255. ↩

-

Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962), 31. ↩

-

For an extensive analysis of this media underground, see Deirdre Boyle, Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997). ↩

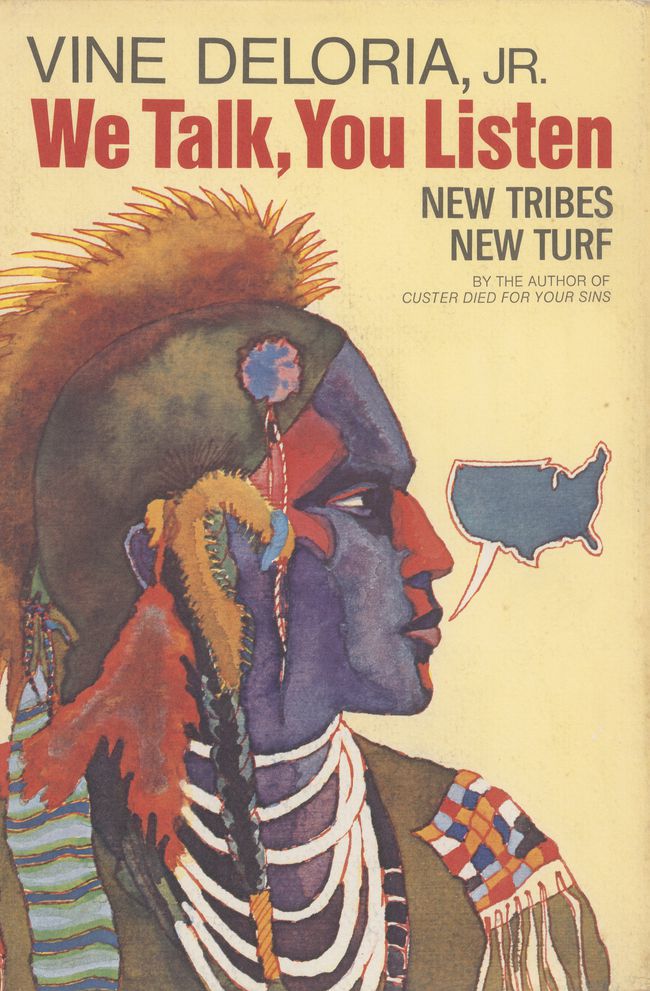

As practitioners took McLuhan’s theories as inspiration for media and social experimentation that drew loosely from a range of cultural domains, Indigenous scholar and activist Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux) offered a more grounded response. Deloria recontextualized McLuhan’s metaphor within the lived experiences of actual Indigenous communities, recognizing the political potential of a more literal reading of contemporary “retribalization.” While counterculturalists appropriated Indigenous references as mystical grounds for a cultural synthesis to come, Deloria asked how Indigenous communities might be treated in the present—not as symbolic fodder or markers of an idealized past, but as social models to inform the design of sustainable livelihoods. As he argued, “Tribes are not vestiges of the past but laboratories of the future.”1

Deloria described the cultural crisis of the 1960s and 1970s as the result of a collective “lack of understanding of the movement toward sovereignty.”2 Echoing McLuhan, he argued that society was “reverting to pre-Columbian expressions, although modified by contemporary technology.”3 In addition to presenting Indigenous forms of community and organization, his writings analyze the autonomous worlds created by American corporations, the Black Power movement, the counterculture, and religious sects as new forms of the tribe, arguing that their respective calls for the right to establish local customs and design the shape of life within their own communities echoed the longstanding political struggle of Indigenous peoples. The “recognition of groups as groups” and the creation of “means of integrating the rights of groups” in processes of governance would be crucial to mitigating the social conflicts that accompanied the rise of this local collective consciousness and grappling with the upheavals of McLuhan’s electric age.4 “ONLY minority groups can have an identity which will withstand the pressures and the tidal waves of the electric world,” Deloria emphasized.5

-

To Protect the Constitutional Rights of American Indians, 1965: Hearing on S. 961, S. 962, S. 963, S. 964, S. 965, S. 966, S. 967, S. 968 and S.J. Res. 40 Before the Subcomm. on Constitutional Rights of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 89th Cong., 1, 194–95 (1965) (statement of Vine Deloria, Jr., Executive Director of the National Congress of American Indians). ↩

-

Vine Deloria Jr., We Talk, You Listen: New Tribes, New Turf (1970; repr., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007)127. ↩

-

Deloria, We Talk, 177. ↩

-

Deloria, We Talk, 136. ↩

-

Deloria, We Talk, 116. ↩

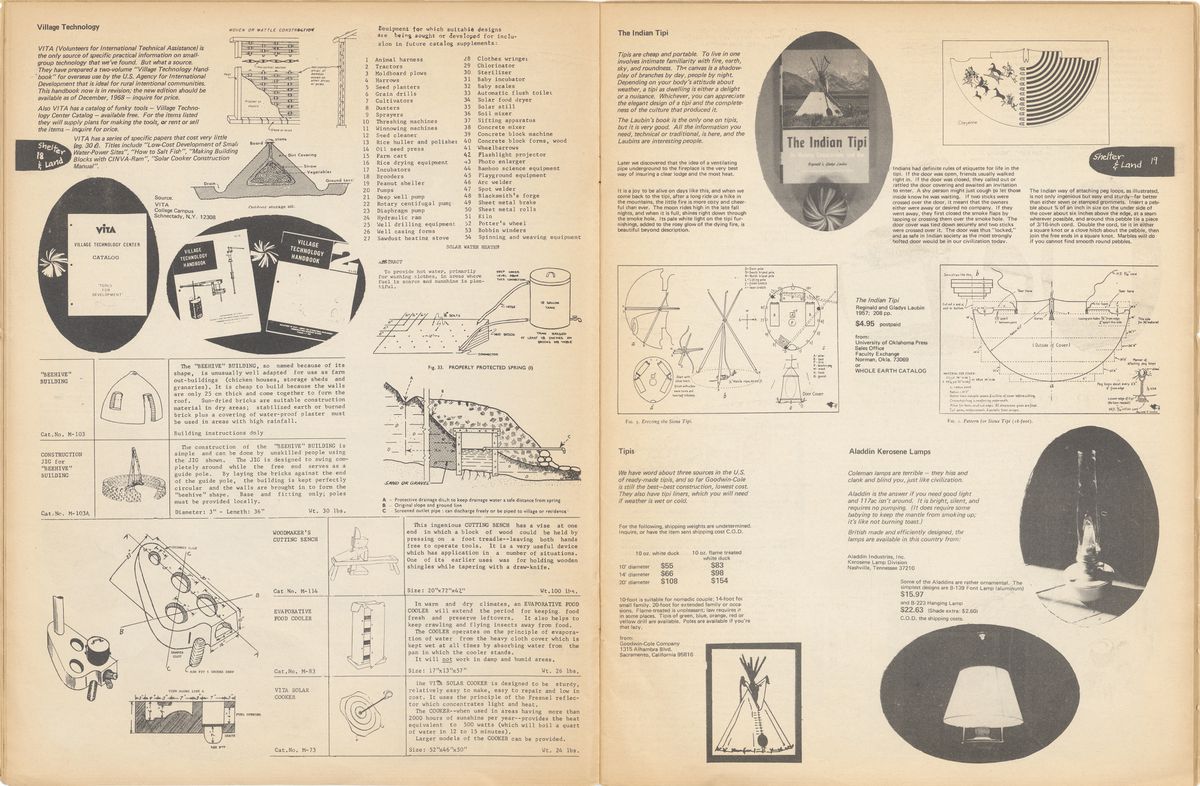

Deloria’s writings spoke to a politics already in practice within Indigenous communities. In her remarks on the San Francisco shore, Buffy Sainte-Marie alluded to the extent of Indigenous grassroots initiatives across the United States: “We have programs in Chicago; we have big brother and sister programs and breakfast programs; we have health clinics all ready to go; we have programs to take care of the people who need help. We have programs in Boston and Chicago and Los Angeles. In Denver, in Cleveland, in Minnesota. In New York City. Just about any place you can name.”1 For Sainte-Marie, the design of such community-led interventions was an effort to create autonomous Indigenous spaces of the sort that already existed for other cultural groups in the United States:

The problems have been spelled out one hundred times. We’ve known what they are….Now here’s some ideas: Let’s think about starting our own businesses—small businesses, Indian run, Indian owned and all of that—so that city Indians can come to a store where they won’t get taken for a ride. An Italian can go to an Italian store; a German can to go a German store; a Jew can go to a Jewish store and on and on and on. We get screwed by everybody.2

Programs of the sort Sainte-Marie described were being developed across Indigenous communities at the time, from “survival schools” in the urban Midwest that worked to maintain and transmit traditional knowledge, to industrial interests owned and managed by reservations.3 This practice of sovereignty through independent initiative was common within other struggles at the time as well. The Black Panthers, for instance, placed food, education, and publication programs at the centre of their mission, creating a parallel, self-sustaining social realm in the face of systemic racism. Many such initiatives found federal support. Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty established Community Action Agencies in the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act, an effort to decentralize government aid to ensure its delivery in a manner consonant with grassroots needs.

While such programs might seem to bear little connection to the experiments conducted by Brand and others in the counterculture, Deloria noted a continuity between these community initiatives and the counterculture’s efforts to articulate alternative futures. As he argued, “When the hippies began to call for a gathering of the tribes, to create free stores, to share goods, and to gather all of the lost into communities, it appeared as if they were on the threshold of tribal existence.” Yet while Deloria credited the counterculture with facing the world’s retribalization “head on,” he argued that these efforts were doomed to fail, not because of circumstance, but “by rejecting customs”—those local values (and obligations) central to meaningful collective life.4 In thinking at the levels of the liberated individual and the universal system, the alternative visionaries of settler society had elided what they professed to re-establish—the group, the community, the tribe.5

-

Video Free America videotape. ↩

-

Video Free America videotape. ↩

-

For example, see Julie L. Davis, Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013); and Steiner, New Indians. ↩

-

Deloria, Custer Died, 231–32. ↩

-

In Counterculture to Cyberculture, Turner notes the dominance of individual leaders within the counterculture and new communalism—often affluent, white men—as well as the importance of these late mid-century experiments in establishing contemporary techno-libertarianism. ↩

This text is an excerpt from Prospects Beyond Futures: Counterculture White Meets Red Power, a book resulting from Robert J. Kett’s participation in the CCA’s Emerging Curator Program. The author thanks those who have shared their thoughts, experiences, and advice as this project took shape: Meredith Carruthers, Ilka Hartmann, Shari Huhndorf, Anna Kryczka, Donald MacDonald, Caroline Monnet, Joey Montoya, Alessandra Ponte, Paul Chaat Smith, Fred Turner, LaNada War Jack, and many others.