Pictorial Storytelling

Warebi Gabriel Brisibe and Ramota Obagah-Stephen propose “other” research methods on colonial housing

For studies within and about sub-Saharan Africa to be non-Eurocentric, they ought to, as much as possible, be conducted and disseminated using the means of cultural expression and communication of pre-colonial societies. And text is certainly not the most well-established of these. Rather, the cultural heritage of sub-Saharan Africa has long been recorded and shared through various oral and visual media: including songs, stories, and chants; relief and round sculpture; motifs, signage, and patterns on textiles, walls, and skin; and sketch art. The application of such non-textual devices as research tools can itself become a study in “other” methods—ones that may better encompass subaltern voices, identities, and systems. By adopting the term “other” to signify the production of “other” knowledge, this research emphasizes the importance of seeing, imagining, and knowing the world from outside a pre-established Western purview.1 More specifically, it adapts “other” methodologies—in this case storytelling and sketch art—to study a distinct residential courtyard type commonly built in historic Port Harcourt Township, Nigeria, from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. The proposed method, named pictorial storytelling, brings together variations of two traditional oral and visual methods of data collection and interpretation, to extrapolate and share silenced voices from Indigenous communities.

-

Morgan Ndlovu, “Coloniality of Knowledge and the Challenge of Creating African Futures,” Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 40, no. 2 (summer 2018): 95–112. ↩

Focusing on Nigeria’s late colonial to early postcolonial periods, the research follows a narrative about Nigerian builders in Port Harcourt who systematically replaced the colonial influences in their own residential architecture, by integrating cultural concepts borrowed from neighbouring or foreign societies. It is their very refusal to comply with predetermined colonial designs, specifications, and delivery deadlines that makes the development of this specific architecture relevant to broader scholarship on postcolonial histories. This struggle to be free to build as one’s culture dictates is synonymous with ideas of nationalism, liberation, and therefore processes of decolonization. Based on the broader notion that buildings constitute the most substantial material culture of any given society, and so reflect the ideas and experiences of its people at a particular, pictorial storytelling attempts to foreground “other” perspectives in the architecture history of Nigeria.

Storytelling As method

The oral tradition is, as we know, common to most colonized societies and therefore key to developing contextually specific research. Oral literature, or what Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o refers to as orature1—proverbs, stories, legends, poems, riddles, songs, and chants—is rooted in sub-Saharan African societies (more so than its counterpart literature) not only as a means of transmitting history but also a cultural practice.2 A common form of orature among Nigerian elders, used to hand down histories and traditions to younger generations, is storytelling—a narrative approach to recording feelings, attitudes, and responses toward one’s lived experiences and environment through voice and gesture.3 Its practice encompasses all things spoken, implied, and even left unsaid through intentional silence, as well as expressed in body language; the story itself must have a traditional structure (introduction, body, and conclusion) and include allegories to enhance its significance.4 Although it is first a method of relaying actual experiences, storytelling also reveals how cultures may be considered natural and unquestioned because it encompasses all aspects of oral folklore.5

Most importantly, storytelling can be considered a method because the aspect of “telling” highlights the process of narration itself and not just the story as a product. It is a more precise method than “oral history,” which remains a method of interview like storytelling but, unlike storytelling, is not itself an act of culture-making. In addition, while oral history interviews are often guided by the interviewer, the process of storytelling is fully controlled by the narrator. Despite good intentions, oral histories can therefore reproduce passive stereotypes and reinforce Eurocentric grand narratives, hierarchies, dichotomies, and methodologies. Storytelling on the other hand, as Métis filmmaker and education scholar Judy Iseke writes, “is a practice in Indigenous cultures that sustains communities, validates experiences and epistemologies, and nurtures relationships and the sharing of knowledge.”6

In the case of the history of residential architecture in Port Harcourt Township, the need to validate experiences and share knowledge is imperative because the only surviving written accounts are documents, reports, and correspondence of the colonial government. Naturally, these reports do not capture the experiences or voices of Indigenous builders. However, what they do record are the contradictions, controversies, and non-compliance charges that hindered the ability of inhabitants to build. For instance, in one report from the late 1950s, the district officer states that there had been deviations from approved building plans in a particular residential construction in Port Harcourt Township and he blames it on the negligence, incompetence, and dishonesty of the building inspectors, who were Indigenous. He accuses these inspectors of collecting bribes and allowing local builders to contravene the colonial regulations.7 Although the accusations were not substantiated and Indigenous builders and inspectors had no opportunity to air their grievances or defend themselves, another report confirmed that no building plans were to be approved until new rules had been officially communicated.8

-

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, “The Language of African Literature,” in Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory, eds. Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman (London: Routledge, 2014), 435–457. ↩

-

For example, sonic archives show that through lyrics, Indigenous singers push their languages to new limits by coining new words and expressions and expanding their capacity to incorporate new happenings in Africa and abroad. See Dele Adeyemo’s forthcoming research for Centring Africa: Postcolonial Perspectives on Architecture, 2019–2021, CCA. ↩

-

Olusegun Gbadegesin, “Destiny, Personality and the Ultimate Reality of Human Existence: A Yoruba Perspective,” Ultimate Reality and Meaning 7, no. 3 (1984): 173–188. ↩

-

For more on the practice of storytelling in the African context, see Emmanuel Matateyou, An Anthology of Myths, Legends, and Folktales from Cameroon: Storytelling in Africa (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. 1997); Maurice Taonezvi Vambe, African Oral Storytelling Tradition and the Zimbabwean Novel in English (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2004); Emmanuel Obiechina, “Narrative Proverbs in the African Novel,” special issue, Research in African Literatures 24, no. 4 (winter 1993): 123–141. ↩

-

Kathleen Marie Gallagher, “In Search of a Theoretical Basis for Storytelling in Education Research: Story as Method,” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 34, no. 1 (2011): 49–61. ↩

-

Judy Iseke, “Indigenous Storytelling as Research,” International Journal of Qualitative Research 6, no. 4 (2013): 559. ↩

-

Report by District Officer Mr. O.R. Wacher. No.C.24/61, National Archives of Nigeria, in Enugu. ↩

-

Report by District Officer Mr. O.R. Wacher. No.L.2547/7, National Archives of Nigeria, in Enugu. ↩

How, then, could we uncover the reasons for and manifestations of the resistance of Port Harcourt Township builders and inspectors? Since storytelling hinges on moral tenets such as truth, justice, and equity, we applied it as a method of fieldwork to capture the convictions, experiences, and struggles of the narrators and therefore embody the positionality of their previously silent voices. The participants in our research were all between sixty and ninety years old and considered elders in the community.1 We hoped they would offer us accounts of memorable events and childhood experiences, of the independence movement, of the Nigerian Civil War, and of personal encounters with colonialists told to them by their parents. The length of each event recaptured as a story told by an elder varied, such that the process of storytelling could stretch over several days. Inspiring such sustained narratives requires a conversational atmosphere, so we observed some traditional practices common to Indigenous people of the Niger Delta to establish a relationship with each elder. To build this a foundation, our method included the following steps:

1. We presented wine, spirits, or other gifts to the elder upon arrival, to reflect our good intentions and our understanding of and compliance with traditions. This helped soften the ground, encouraging the elder to give us access and to commit to speak the truth.

2. We had a single agenda for each meeting, beginning with simple, unstructured, and open-ended questions followed by a request for a story. Structured interviews with frequent reference to written notes are often counterproductive to creating a conversational atmosphere. If we had multiple agendas, further meetings were scheduled, as elders typically appreciate visits from younger guests.

3. We allowed for deviations without interruption. Sometimes an elder would go on an apparent tangent, yet the vital narrative links would often be made at the end of the story.

4. We listened to the messages conveyed via the unspoken: gesticulations, underlying tones, sarcasm, throat and muffled sounds, body language, facial expressions, and pauses or silences.

5. We participated in the conversation and answered questions. Traditional African processes of storytelling are often interactive, such that the positionality of the interviewer as an outsider and listener can be reversed. For example, many chants or songs given during storytelling are statements or questions to which the listener is expected to respond.

Interestingly, the first point in our storytelling method contradicts the American Sociological Association Code of Ethics, according to which researchers are not permitted to “offer excessive or inappropriate financial or other inducements to obtain the participation of research participants,” but after completion of the interview or survey they are expected to “provide appropriate incentives as an acknowledgement of participants’ time and inconvenience incurred by participation in the study.”2 However, what is considered an inappropriate incentive is culturally specific, particularly in regard to different Indigenous societies within which offering gifts, participating in ceremonies, or sharing meals are standard social practices and an essential signs of respect but are, as Judy Iseke notes, not recorded as part of the research process.3

Such practices appear at odds with the ASA Code of Ethics, which begs the question: who decides what is ethically appropriate? Western, academic standards in social science research are not universally applicable because they do not take into account the unwritten cultural guidelines of Indigenous societies. In developing our method, we instead learned from Māori education scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith, who identifies conventions such as debate, formal speech-making, and structured silences as crucial tools for conducting fieldwork and developing pedagogies through decolonizing methodologies. She surmises that oral arts and other forms of expression frame Indigenous communities according to their own cultural and historical references, noting that “texts can only be successful as a depicting of culture if writers capture the ways in which the colonized actually use language, their dialects and inflections and in the way they make sense of their lives.”4 An Indigenous research methodology is therefore a unique framework with its own epistemological autonomy that provides its own sets of rules and methods of engagement.

-

Interviews could only be arranged via referrals. The level of relationship or respect between the proposed interviewee and the referee determined to a large extent the interviewees’ willingness to participate and to share personal experiences, family history, and prized values and knowledge. ↩

-

Rule “12.3 Inducements for Research Participation,” in American Sociological Association Code of Ethics (June 2018): 15, https://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/asa_code_of_ethics-june2018.pdf. ↩

-

Iseke, “Indigenous Storytelling as Research,” 561. ↩

-

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Press, 1999), 35. ↩

Sketch Art as Method

The second method we adopted was sketch art, a means to give visual expression to the lived experiences of those participating in our research. We sought to graphically re-enact the historic social landscape of Port Harcourt Township during the late colonial and early postcolonial era by retelling stories through imaginative pictorial scenes. In particular, we wanted to depict socioeconomic issues associated with the planning of residential development schemes in the study area.

There is a long tradition in Africa of representing social landscapes through visual forms of expression, including murals, motifs, etchings, prints, relief sculpture, glyphs, and patterns. A notable example from ancient history is the bronze relief sculptures of the Benin Empire, in modern-day Nigeria, that depict ceremonies for the Oba, the divine king. Such visual documentation can be read as either a way to disseminate information—clear record-keeping—or a way to code metaphoric concepts, whereby graphic elements represent a being or person, a phrase or word, or even an idea. As art historian Elizabeth Boone and semiotician Walter Mignolo note in Writing Without Words, the way ancient Mesoamerican and Andean peoples communicated and “conveyed meaning through pictorial, hieroglyphic, and coded systems” challenged orthodox “notions of literacy and dominant views of art and literature.”1 In the case of African sketch art, realism is generally not the primary mode of representation; rather, methods of abstraction or stylization are commonly employed, ranging from what expressionists termed primitivism (an expression of their own idea of nature) to simplified, geometric forms. But as contemporary African artists and tutors, Awogbade Mabel and Ibenero Ikechukwu observe, such abstractions are nonetheless laden with social, religious, political, and economic meaning2—embodying the systems and values of Indigenous people and negating Eurocentric standardizations and positionalities.

Furthermore, in contrast to the immediacy of visual methods like photography, sketch art can simultaneously capture the present, recreate the past, and project future moments. While photographs document the evidential qualities of a subject without interfering with reality, sketch art highlights the evident and not-so-evident, the fact as well as the fiction. This makes it a particularly interesting method when used in situations when photography is inappropriate or simply prohibited—such as in a court room. According to Anita Lam, a Canadian social scientist in criminology, courtroom sketch art encapsulates much more than a simple visual representation; it can be read. She argues that the method not only describes legal proceedings but also “bears the imprints of [the artist’s] bodily sensations and bodily activities, including their bodies’ shifting attention, physical movements, and embodied emotional experiences.”3 In essence, it can be used to capture law-in-motion.

-

Elizabeth Boone and Walter Mignolo, Writing without Words: Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1994), book summary. ↩

-

Awogbade Mabel and Ibenero Ikechukwu, The Use of African Traditional Art Symbols and Motifs: Study of Some Selected Paintings of Tola Wewe (Germany: LAP Lambert Academic Publishers, 2010). ↩

-

Anita Lam, “Artistic Flash: Sketching the Courtroom Trial,” in Synesthetic Legalities: Sensory Dimensions of Law and Jurisprudence, ed. Sarah Marusek (London: Routledge, 2017), 133. ↩

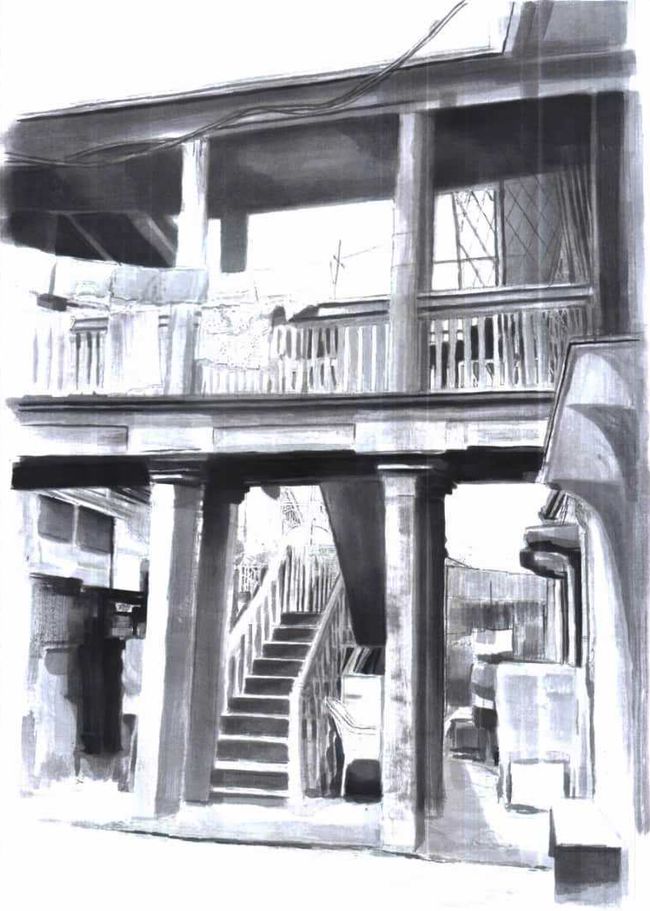

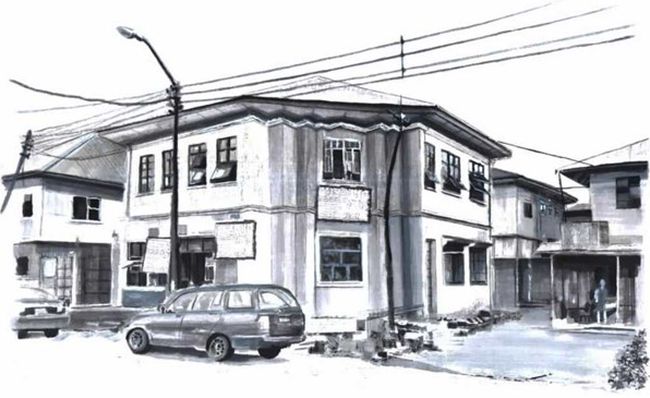

Similarly, sketch art can be used to capture postcolonial perspectives-in-motion by acting as a tool for documentation, interpretation, and analysis. For example, the sketch above was initially produced while conducting fieldwork in historic Port Harcourt Township. The building in the foreground, constructed in 1948, is an early example of residential type that incorporates a home-business—in this case a convenience store—on the open-plan ground floor, typically with a living area and adjoining bedrooms on the upper floor and a detached kitchen and toilets. Cordelia Osasona, a leading Nigerian scholar on heritage and vernacular architecture, attributes this building type to the influences of early “Saro” (Sierra Leonean) immigrants in Lagos.1 Two other examples of historic residential buildings in Port Harcourt Township that were designed with home-businesses include one with an architecture office and the other with a laundry service. The sketch of the house with convenience store attempts to depict the sense of pride the building embodies and the important position it holds amongst the surrounding dwellings, as well as of the daily lived experience of the neighbourhood. Although produced in contemporary realism, it intentionally leaves out people, making the building the protagonist. In doing so it positions the sketch as the tool of a storyteller who directs the plot, by choosing which angles to view experiences from, what events, details, and narratives to focus on, and what to blur and what to highlight—in other words, how to visually represent and interpret a narrative.

-

Cordelia Osasona, “Nigerian Architectural Conservation: A Case for Grass-roots Engagement for Renewal,” International Journal of Heritage Architecture 1, no.4 (January 2017): 713–729. ↩

“Other” Methodologies

Pictorial storytelling is a process of experimentation in forming “other” methodologies. Though rooted in Indigenous African traditions of orature and documentation, it is also simply a less intrusive means of depicting and interpreting narratives of the people and places figured in colonial and postcolonial histories. However, though the role of the research may seem more marginal, pictorial storytelling, much like court art, still clearly bears some imprint of the researcher’s own cognitive frameworks and requires the researcher’s participation in the setting and with the subjects. The pictorial storyteller directs the plot, choosing which angles to view experiences from, what events, details, and narratives to focus on, what to blur and what to highlight, and, most importantly, how to visually represent and interpret. Ideally, however, such interpretations would be produced by Indigenous researchers or subaltern voices. In this way, pictorial storytelling can privilege an Indigenous positionality, thus provoking inquiry and engagement with Indigenous epistemologies to produce decolonized knowledge—or to correct existing colonial knowledge.

Warebi Gabriel Brisibe and Ramota Obagah-Stephen wrote this text as part of their research for the Multidisciplinary Research Project Centring Africa: Postcolonial Perspectives on Architecture.