The Modernizing Beat

Dele Adeyemo rereads the production of space in a modernizing Ghana through highlife

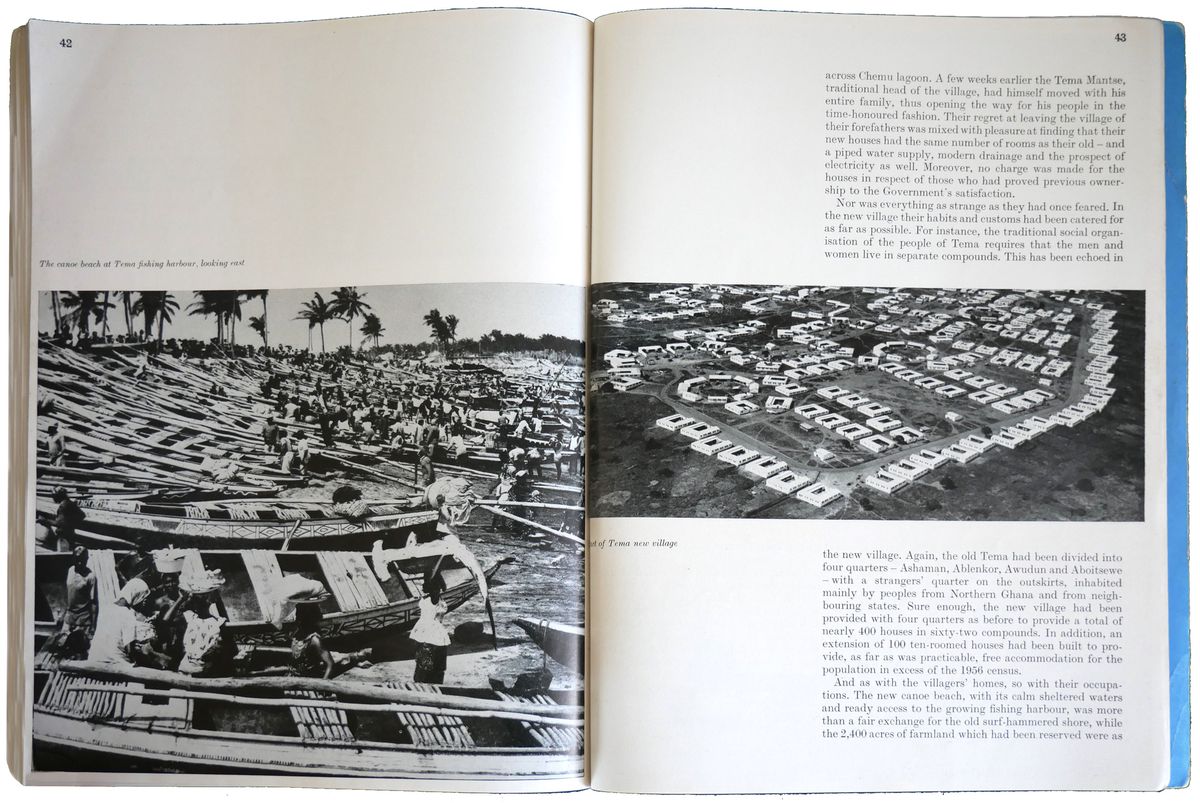

As the sound of metallic, rhythmically beating cowbells mingles with that of the recurrent rumbling, crashing surf, a single melodic voice rises with a call and a troupe of deep, buoyant tones responds in a harmonic chant. This is the traditional polyphonic sound system of a Ghanaian fishing community, filmed on a beach in 1964, sixty kilometres north east of Accra. The film shows a group of around thirty people as they work collectively to draw their ocean fishing net back to shore.1 As the cowbells ring and the mellifluous singing rises, the group marches slowly backward in step, tugging at a single rope that stretches out into the bay, bobbing up toward the sky and down again, giving a collective bounce to their gait. The men and boys are dressed in white shorts and fedora hats, most often with no shirts, like a singular body of sixty arms and sixty legs tethered by a single cord. As the film rolls, women wearing wrappers and dresses made of imported, printed fabric take hold of the line and lend their strength to the seaside tug of war.2 The final shots show the community members dividing up the catch; some fish will be eaten together and the rest will be sold at market.

The film was made by the Seegers, a famous American family of folk musicians, during their ten-month world tour. To the unfamiliar viewer, the scene conveys an image of Ghanaian society as an exotic, almost premodern, tropical idyll. How much was staged is unclear, but what is clear is a culture in which sound and rhythm organize collective life: an intergenerational group using song to synchronize their work—a “sonic body.”1 The young adults in the group might have laboured on the beaches during the day and then, in the evenings, flocked to town centres, where they could dance to the rhythm of their work song relayed by young musicians with modern instruments. The beat became popularized as a sound called highlife, which rose to be Ghana’s preeminent artform by 1957, when the country became independent from British colonial rule. Highlife, as both music genre and lifestyle, was carefully orchestrated by Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first Prime Minister, and his new government to manifest a culture that would appear exclusively African in origin—part of his mission to invent a national identity rooted in a vision of collectivity and modernity. In reality, the roots of highlife date back to early exchanges between Europeans and Africans in the urbanizing coastal centres of West Africa. The music reflected the region’s transition from a society based on subsistence farming and fishing to one in which lifestyles were conditioned by the architecture and infrastructures of modernity.2

-

Julian Henriques, Sonic Bodies: Reggae Sound Systems, Performance Techniques, and Ways of Knowing (New York: Continuum, 2011). Henriques centres Jamaican culture as a primarily sonic culture by positioning audition and a sense of sound as embodied forms of knowledge that have often been sidelined by dominant visual practices of knowledge production. ↩

-

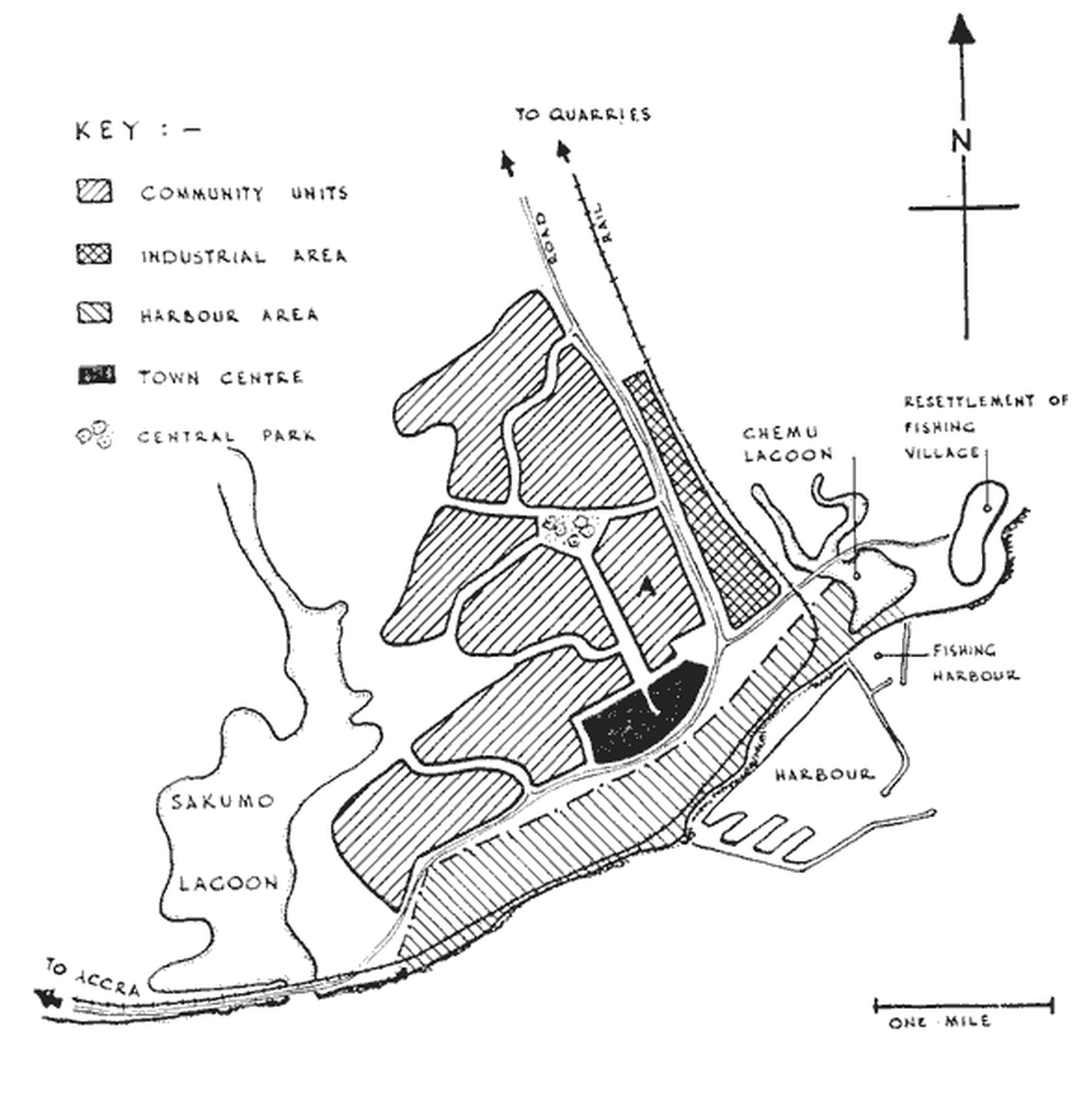

Tema Harbour and New Town, the site of this research, might be understood as an assemblage of infrastructures consisting of the deep-water harbour, the industrial factories, the housing for workers, and the connecting road and railway networks. ↩

Constituting an archive through highlife

Given that Ghana was a leading nation in African decolonization and modernization, histories of its changing urban environments tend to foreground the political-economic decisions and top-down strategies of the nascent independent state. As a result, the everyday cultures, motivations, and desires of people and their role in the production of space often remains unaccounted for. Opening up spatial histories to consider highlife foregrounds the cultures circulating within the Atlantic world that were brought into contact through logistical forms of planning, therefore enabling an alternative route into architecture analysis.

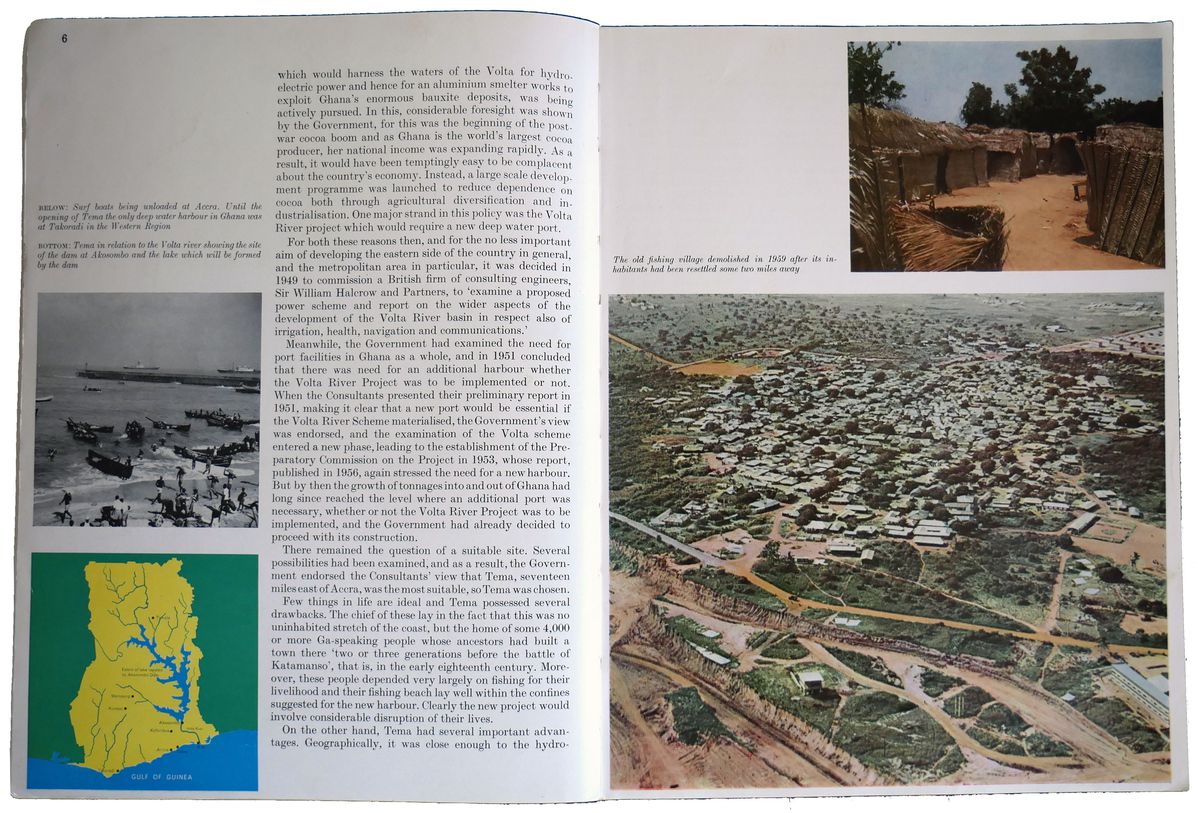

Even as the Seegers were filming, another nearby fishing town called Tema was being rapidly transformed by the construction of an advanced deep-water seaport. From the perspective of the longue durée, the evolution of West Africa’s coastal architecture has been defined by the emergence of logistical planning.1 This lineage began with the trading posts of the early fifteenth century, where European merchants exchanged goods and commodities with societies along the Guinea coast—sites that soon became the ports and castles central to managing the flow of bodies within the Atlantic slave trade. From the nineteenth century on, these coastal hubs became the critical infrastructures of colonial rule, where railway lines emerging from deep inland converged to efficiently extract natural resources. Finally, in the twentieth century, the harbours were expanded into mega seaports capable of supplying the growing local consumer market with imported, manufactured goods and increasing the export of raw materials. The development of Tema Harbour, begun during the late colonial period and accelerated after independence, therefore represents a continuity of the logistical planning that shaped geographies and modified traditional ways of life, dictating processes of urbanization in Ghana. So, although Tema was fundamental to Nkrumah’s political project to decolonize Ghana through industrialization, it also perpetuated, and in fact intensified, a modernizing logic ever-present since the intervention of Europeans.

-

Recent scholars have argued that modernity emerged from the relationships forged through the Atlantic slave trade. See Robin Blackburn, The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492-1800 (London: Verso, 2010); Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Wivenhoe, UK: Minor Compositions, 2013); Charmaine Chua et al., “Turbulent Circulation: Building a Critical Engagement with Logistics,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36, no. 4 (August 2018): 617–629. ↩

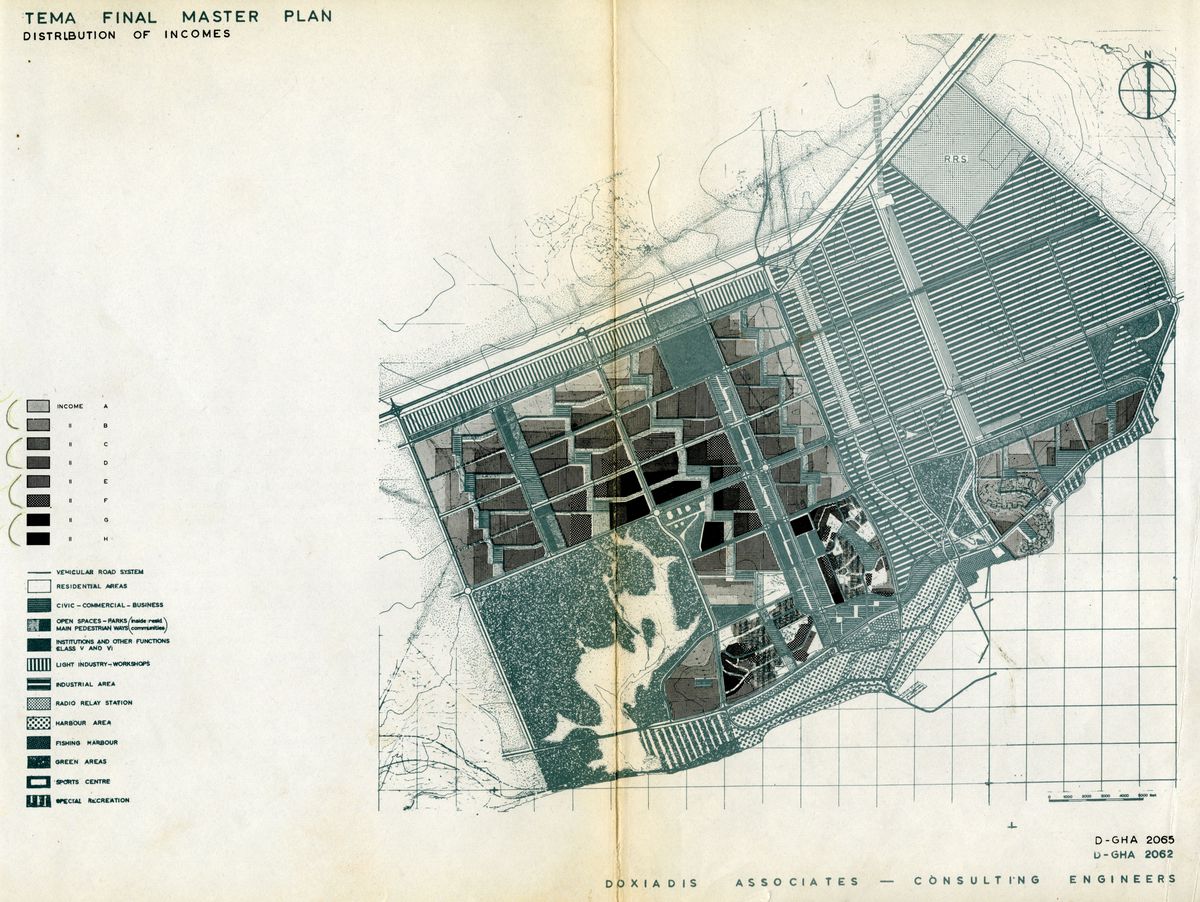

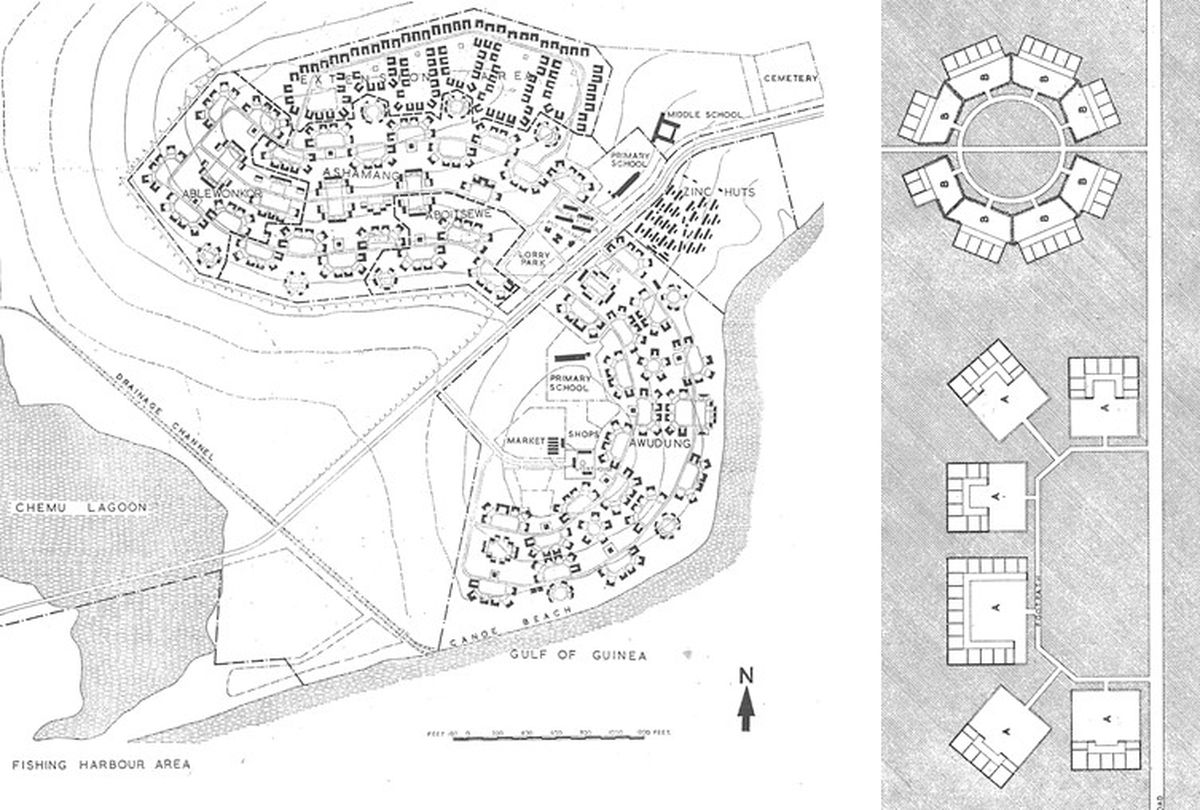

In parallel with the port development, Tema New Town was conceived of both to relocate the displaced fishing village and to create housing fit for a modern, independent African society. The masterplan was a demonstration of how a modernist urban model could be, in theory, imported into Africa by Europeans. The initial plans, developed by Alfred Alcock, Maxwell Fry, and Jane Drew, translated the English new town for the continent, resulting in the development known as Tema Manhean. In 1960 however, frustrated at the rate of progress, Nkrumah employed the Greek planner Constantinos Doxiadis to develop an even more efficient masterplan.1 The architecture archive of the Tema Harbour and New Town project therefore overwhelmingly privileges these European perspectives. Fry and Drew’s drawings and journals cover the initial design development during the late colonial period, while Doxiadis’s cover design strategies developed in the years after independence. Fry and Drew’s archives contain detailed accounts of their lives, relationships, and desires, but relatively little reflection on the views of the people they were designing for. Similarly, Doxiadis’s archives contain copious technical detail of the design strategy and progress, while only a brief sense of local perspectives can be gleaned from the strained correspondence with Nkrumah’s administration. Even though both firms referenced local typologies in their plans, the archive offers only a self-contained, almost singular historical view and presents a narrative of the conception of architecture as a linear exercise in fulfilling a design brief that, in this case, excluded the cultural complexities of the context that brought that architecture into being.2

-

For more on the history of Tema and its modernist planning, see Michelle Provoost, “Exporting New Towns: The Welfare City in Africa,” International New Town Institute, 2015, http://www.newtowninstitute.org/spip.php?article1046. ↩

-

This is not so much a critique of the architects themselves, but rather of the skewed perspective of archives that centre the more readily available work of architects, planners, and other building consultants. ↩

So how might these narrow, disciplinary specific archives be enlivened and contested through highlife? Taking up the imperative that Stuart Hall sets out in his essay “Constituting an Archive,” the challenge of this research is to constitute a living archive, in which “living means present, on-going, continuing, unfinished, open-ended.”1 If the beat of highlife’s precursor, the work song, bound the community together in collective life that was attuned to the rhythm of the tides and cycles of the seasons, then perhaps the evolution of the highlife sound can tell a story about how the circulation of cultures, commodities, and political-economic structures condensed into the spatial forms of a modernizing Ghana. By thinking through, or rather sounding, highlife as a sonic body of knowledge and form of testimony that centres the lives of Africans, music may act as a counterpoint to the typically visual representations of space contained within architecture archives and as a tool to reassess the key spatial agents involved in the production of the modernist development of Tema Harbour and New Town.

-

Stuart Hall, “Constituting an Archive,” Third Text 15, no. 54 (March 2001): 89. ↩

The dance band and the African Personality

As the Atlantic slave trade intensified through the 1600s and 1700s, West Africa’s coast was populated by numerous urbanizing settlements, only for them to be gradually consolidated during colonial rule around ever-larger port towns.1 These sites became cosmopolitan centres, where Europeans and Africans from across West and Central Africa, as well as the African diaspora in the Caribbean and North and South America, came into contact.2 It was here that highlife took shape, hybridizing—and therefore recording—the range of cultures entangled in Ghana’s urbanization over several centuries. The evolution of highlife therefore highlights the often-overlooked West African dynamic of Black Atlantic culture by drawing attention to the fluid, transnational cultural exchanges of a Black diaspora that not only coalesced in the Global North but were very much present in Africa too.3

As the historian John Collins describes, Ghanaian highlife is the earliest significant form of West African neo-folk music, fusing traditional dance rhythms and melodies of the Akan people with instruments and harmonies brought from Europe.

Highlife originated on the Fanti coast of southwest Ghana, which has the longest history of European contact in West Africa (the Portuguese built Elmina Fort there in 1482). The Fanti had their own dance musics, of course, including recreational styles, and in the port towns that grew up around the European forts it was these which were particularly susceptible to foreign musical influences, such as military marching music and popular Western songs. These were played by the regimental fife and brass bands composed of European-trained local musicians—a tradition going back to the fort bands of the eighteenth century. Another influence was the sea shanties and folk songs introduced by sailors, including blacks from the West Indies, Americas, and neighbouring West African countries. Some of the earliest highlifes were played on sailor’s instruments like the guitar, harmonica, and concertina… Finally, there were the piano music and hymns introduced by the missionaries and popular with the Christian educated black elite.4

-

H. P. White, “The Morphological Development of West African Seaports,” in Seaports and Development in Tropical Africa, eds. B. S. Hoyle and D. Hilling (London: Palgrave Macmillian, 1970), 11–25. By 1965, the number of ports in Ghana had fallen from thirty to only two. ↩

-

These diaspora communities included: slaves transported from West and Central Africa; sailors from the West Indies; in the mid-nineteenth century, Afro-Brazilian returnee slaves; West Indian soldiers stationed at Cape Coast castle and Elmina castle by the British colonial administration in the late nineteenth century; and in the early twentieth century, Kru seamen and stevedores from Liberia as well as those enticed by Markus Garvey’s Black Starline and the Back-to-Africa movement. ↩

-

See Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and the Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993). With a particular emphasis on black music and black vernacular culture, Gilroy foregrounds the hybridity and transnational mixing of ideas that emerged in the Global North. While this offers a template for resisting ethnic and national culturism, Gilroy omits discussing the production of music on the continent of Africa through transnational cultural exchanges. For a critique of this omission, see Boluwatife Akinro and Joshua Segun-Lean, “Beyoncé and the Heart of Darkness,” Africa Is a Country, 15 September 2019, https://africasacountry.com/2019/09/beyonces-heart-of-darkness. ↩

-

Collins also highlights Liberian influences: “Kru sailors and stevedores from Liberia were famous both as seamen and guitarists; Kwame Asare or ‘Sam,’ the earliest notable Akan highlife guitarist, was taught by a Kru.” E. John Collins, “Ghanaian Highlife,” African Arts 10, no. 1 (October 1976): 62. ↩

In the years between World War I and II, highlife was disseminated from the port towns throughout the rural hinterland. While the band emerged as the dominant medium of transmission, it became separated into two distinct forms for different audiences: on one hand, high-class dance bands and orchestras performed for the sophisticated, black elite in the towns, and on the other, a variety of palm-wine guitar bands entertained the poor and less educated population in rural areas.1 With the upheaval and restructuring of old colonial orders in the years after World War II, highlife again transformed dramatically, evolving first into smaller dance bands that integrated influences from swing, Afro-Cuban percussion, and calypso and then into a style inspired by bebop and modern jazz.2 Finally, in the 1960s, Western pop music arrived in West Africa and by the 1970s it became so popular that the existing dance and guitar bands had to incorporate this foreign genre into their repertoire.3 Highlife had become the preeminent sound of modern life not only in Ghana but across West Africa, but bands now began to fuse together influences and create their own distinct sounds that went beyond highlife—the most notable example being Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat emanating from Nigeria, which marked an important evolution in West African popular music.

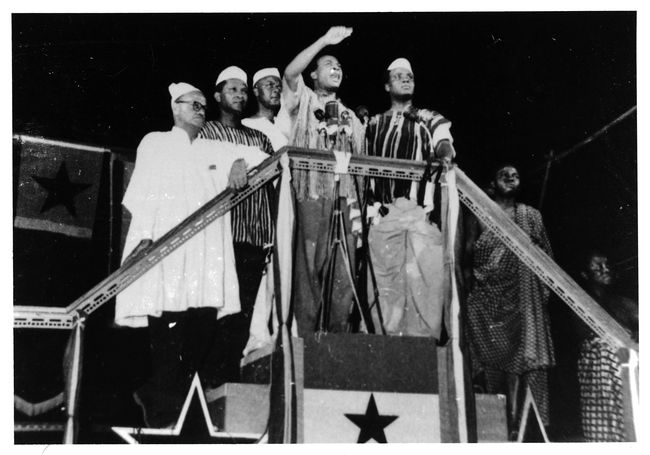

Prior to this, immediately before and after independence, highlife was central to the struggle to redefine the identity of Ghana as the country underwent modernization programmes. While the colonial government had relied on extracting Ghana’s raw materials, especially cocoa, Nkrumah’s industrialization programmes aimed to increase domestic manufacturing and so reduce dependence on imports. Development planning therefore required diversifying agricultural production while also increasing exports in local products and raw materials.1 Subsistence communities with expansive kinship structures, such as the one portrayed in the Seegers’s film, therefore needed to be reconstituted into nuclear families—discreet economic units that could be more readily mobilized to provide workers and consumers for an industrializing society. But what would happen to the frequencies that had traditionally bound together labour and social life? The tempo of the rhythm that people moved to would surely have to be accelerated and it was Nkrumah who best understood highlife’s critical potential to set a modernizing beat. As historian Nate Plageman highlights in “The African Personality Dances Highlife,” by 1960, after having successfully launched a five-year development plan—encompassing industrialization, hydroelectric, communications, and health programmes designed to enable Ghana to “advance confidently as a nation”2—Nkrumah turned his attention to culture. Recognizing the power that highlife had to influence the population, especially urban youth, he announced that Ghana’s diverse popular musical scene was to be reformulated.

First, he declared that highlife was Ghana’s “national” dance music and that it, as well as other local musical forms, deserved priority both in nightclubs and on radio airwaves. Announcing that the country’s popular music scene needed to become more “Ghanaian” in composition and character, he asked popular musicians to limit (and over time eliminate) the performance of foreign numbers, play highlife songs at a uniform tempo, and employ a standardized set of dance steps that nightclub crowds could emulate while on the dance floor.3

-

Kwame Nkrumah, Africa Must Unite - New Edition (London: Panaf Books, 2007), 108–11. ↩

-

Nate Plageman, “The African Personality Dances Highlife: Popular Music, Urban Youth, and Cultural Modernization in Nkrumah’s Ghana, 1957–1965,” in Modernization as Spectacle in Africa, eds. Peter J. Bloom, Stephan F. Miescher, and Takyiwaa Manuh (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014). ↩

-

Plageman, “The African Personality Dances Highlife,” 255. ↩

Kwame Nkrumah announcing Ghana’s independence, 6 March 1957. Nkrumah compels Ghanaians to adopt an “African Personality,” surrounded by the symbol of the black star symbol and wearing the traditional dress of the fugu that he would later endorse as national attire. Image from Nate Plageman, “The African Personality Dances Highlife,” 2014. Courtesy Nate Plageman © Information Services Department of Ghana Photograph Library

Although these pronouncements had little immediate impact, they signalled Nkrumah’s intention to mould Ghanaians into a population capable of fulfilling his vision of a modern African nation. This nation’s culture would be contained within the construct of the “African Personality,” an ideal citizen who embodied a collective identity built on African, rather than foreign, values. Highlife would provide the soundtrack to everyday life, awakening parts of the Ghanaian character that no colonial administration had ventured to rouse.

The contested space of highlife

The emergence of industrial and modernist urban forms such as Tema Harbour and New Town not only restructured traditional and colonial societies but catalyzed new urban cultures—and the African Personality was intended to inhabit such architecture. Nkrumah and his governing Convention People’s Party (CPP) saw the growing numbers of urban youth as an opportunity to promote a culture that would bring citizens together (not unlike in the fishing village) into “an industrial society predicated on hard work, education, and patriotic service.”1 And the tradition of the highlife dance band was seen as a medium to extoll the values, practices, and behaviours that young people could then adopt and emulate.

-

Plageman, 261. ↩

However, as young people broke familial ties and moved to the towns to find work in the new economy, many became disaffected. Suffering from unemployment, widespread housing shortages, and a lack of the basic amenities—particularly in areas excluded from infrastructural improvement programmes—they felt overlooked and betrayed by the party they had voted into power.1 They sought solace and camaraderie in Western pop music, organizing informal, private gatherings on the beach or events in self-operated rock ‘n’ roll clubs, helping to develop a culture of self-reliance centred around non-state-sanctioned music. In turn, many CPP officials considered that these urban youth, by embracing foreign behaviours and practices, were jeopardizing Ghana’s future. In the battle to fashion the minds of the youth, such that they would aspire to the idealized African Personality, the CPP believed it was fighting against outside influences that would perpetuate a form of cultural imperialism. The youth who embraced twist and rock ‘n’ roll were caricatured as having regressed into the colonial mentality they fought so hard to escape.2 On the other hand, young people and musicians believed the foreign sounds infiltrating Ghana best promoted the modern values of their collective urban experience and the spirit of the newly independent nation.

Rock ’n’ roll, they insisted, was not an “unhealthy” music antithetical to “Ghanaian” culture; it was a powerful medium that linked its participants to an international cohort of youth who promoted liberation, celebrated consumption, and publicly combated the depersonalization that generations of Ghanaians had experienced under colonial rule. Numerous youth were convinced that the music’s vibrant beat, flashy style of dance, and corresponding aesthetics were the perfect mediums to announce the end of an oppressive era and celebrate the new freedoms they had claimed since its demise.3

Nkrumah’s real competition over the minds of young people came not from outside forces but rather from the power of self-fashioning emanating from within Ghana itself. And the CPP was in fact responsible for generating the conditions for this new culture to thrive: once modern infrastructure had been deployed on a scale never seen in Ghana, traditional ways of organizing society and community, grounded in the collective rhythms of a subsistence economy and social life, were undone.

The Uhuru Dance Band, a state-endorsed highlife band supported by the Arts Council of Ghana, performs wearing the traditional fugu to adhere to Nkrumah’s “African Personality,” 1963. Image from Nate Plageman, “The African Personality Dances Highlife,” 2014. Courtesy Nate Plageman © Information Services Department of Ghana Photograph Library

Tema Harbour and New Town is one site for examining the relationship between the state-regulated dance band and urban and industrial development programmes. Recognizing “the vital role of local popular entertainment in the independence struggle and the creation of an African identity,” Nkrumah endorsed an array of “state and parastatal bands and concert parties” associated with state-run corporations, such as the Cocoa Marketing Board, Black Star Shipping Line, State Hotels, Armed Forces, the Workers Brigade, and Farmers Council.1 And during Nkrumah’s presidency, industrial developments throughout Ghana, managed by state corporations, continued to integrate performance venues into the design of their complexes and finance dance bands and concert parties that provided their workers with entertainment. In Tema, this practice was still in place in 1973 when the owner of the Talk of the Town Hotel formed Sweet Talks as the resident act, which included several band members who had earlier gained their experience and developed their musical influences by playing in state-sponsored venues across the country. The band leader, Alfred Benjamin “A.B.” Crentsil, had first started playing in the 1960s with other bands at venues affiliated with industrialization projects, namely the El Dorados at the State Aboso Glass Factory in western Ghana and with the Lantics at the State Hotel Corporation. Similarly, the Tema Food Complex, Ghana’s largest food processing plant at the time, financed several of the bands in which other members of Sweet Talks first began playing highlife. As their popularity grew, Sweet Talks created a sound coined the Kusum Beat in 1974, which gained international appeal and led them to tour the United States, demonstrating just how quickly Ghanaian culture shifted away from the state-sanctioned national identity that was supposed to have taken shape, in part, through highlife.

Like the modernist architecture plans for the nascent country, highlife’s role in a modern Ghanaian society exceeded the scope of government control, becoming a medium for urban youth, in particular, to express alternative ways of being from that imagined by the state. Through the contested field of highlife, it is possible to read the internal contradictions of a new nation that embraced the modernism and industrialization of a global trade economy while simultaneously rejecting the influence of global popular culture on its own urbanizing populations. This contradiction was intensified through spaces designed to manifest the promise of the African Personality with the aid of the state-manufactured dance band, such as Tema. In this industrial, urban context, highlife, and popular music in general, came to exemplify not a binary disavowal of the colonial era, as the new government had hoped, but the inscription and articulation of the cultural hybridity of the Black Atlantic through an “in-between” space.2 As a sonic intervention into the architecture archive, highlife, as both music and lifestyle, is able to fill the analytical gaps between the modernist architecture constructed, the logistical and infrastructural vision of a state bent on industrialization, and the lived reality of everyday people.

-

E. John Collins, “Ghana’s Politics Has Strong Ties with Performing Arts. This Is How It Started,” The Conversation, 2 November 2020, https://theconversation.com/ghanas-politics-has-strong-ties-with-performing-arts-this-is-how-it-started-148940. ↩

-

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London; New York: Routledge, 1994), 38. Bhabha, a postcolonial critical theorist, has defined this in-between as a Third Space, based not on the exoticism of multiculturalism or the diversity of cultures but rather on their hybridity. ↩

The CCA has made every reasonable effort to identify and contact the copyright holders of the images that illustrate this article. If you identify any of your work please contact us at copyright@cca.qc.ca.

Dele Adeyemo wrote this text as part of his research for the Multidisciplinary Research Project Centring Africa: Postcolonial Perspectives on Architecture.