A deliberate bombardment of the senses

Dan Handel interviewed by Francesco Garutti and Émilie Retailleau on the strategies behind the deployment of carpets in the deep spaces of hospitality

- FG

- Why did you decide to study the role of carpets in architecture today, and what can we learn from this specific building component?

- DH

- The theme of the carpet in architecture may sound very innocent, as if we are simply discussing how patterns reflect on the history of art and architecture. But that is, of course, not what the exhibition is about. As the title The Design of Carpets that Design Us suggests, the exhibition looks at a specific genre of carpets and tries to evaluate not only their appearance but also their performance in architecture: that is, carpets that are deployed as strategic interventions in buildings to affect orientation, feelings, and perception.

The exhibition topic is contemporary for two reasons: first, because it highlights spaces that explicitly use design to create environments that influence behaviour; and second, because it delves into the logic and the more extreme manifestations of an economic order that is still in place today. - ER

- What is the building type you study in the exhibition, and what economic regime is at play in your narrative?

- DH

- The carpets that we focus on are those that are produced by very big companies for very big brands. The exhibition looks at moments in which the logic that is embedded in the production of such carpets intersects with specific types of buildings, namely the deep spaces of hospitality—hotels, convention centers, and casinos. These megastructures emerged with the advent of artificial lighting and air conditioning and grew to mammoth dimensions in the early stages of advanced capitalism in the late 1960s.

- FG

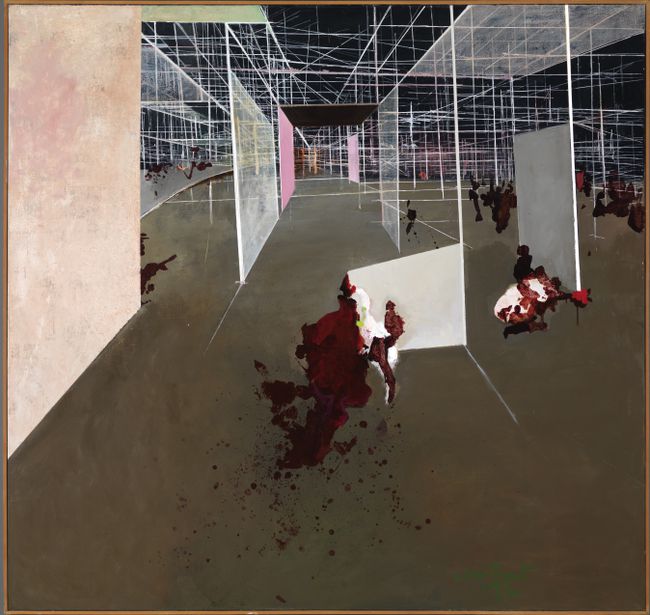

- You introduce these types with a sort of prologue, the painting Entrée du labyrinth by Constant Nieuwenhuys. What’s the relationship between that work and your research on “deep space”?

- DH

- When looking at the carpets in hospitality spaces, I realized there’s an important question to be asked: are architects really in control of their buildings? Can architecture liberate or enslave us? Constant Nieuwenhuys’s New Babylon project is a great point of departure for asking these questions. Not only because it coincides in time with the early deep spaces we present in the exhibition, but because it proposed the idea of homo ludens—the human being living in the future without work—who moves through life with endless creativity, endless freedom, mediated by a maze-like architecture. Constant’s intention was to liberate man by constantly stimulating his senses, and there’s an eerily similar operation taking place in a casino, for instance, only that the same techniques are highjacked in order to make you act in accordance with the intentions of the owners of the space, rather than your own. So here is a tale about the tragedy of an architecture that once sought to liberate us but is now either apathic or antagonistic to our desires.

- FG

- In that sense, did you see any connections with Archizoom’s No-Stop City? Was that considered in your research?

- DH

- I would say, if anything, that No-Stop City is a much more pessimistic project than Constant’s. It took into account the brutal washing of the capitalist logic of accumulation that pervades everything and that turns the city into an infinite isotropic surface.

It’s interesting to consider the psychological states one can imagine to be in when inhabiting these two projects: in No-Stop City, one seems to drift in a dreary state of consciousness, while in New Babylon one is relentlessly stimulated. When I look at Archizoom’s world it seems to me that everybody is apathic and nothing ever really happens. Constant’s world, on the other hand, employs a brutal honesty regarding the effects of his architecture on users, showing playful environments next to gruesome scenes of mass violence.

I think the projects shown in the exhibition have something of both: constant wandering, repressed violence, a deliberate bombardment of the senses, as well as hyper-designed interiors.

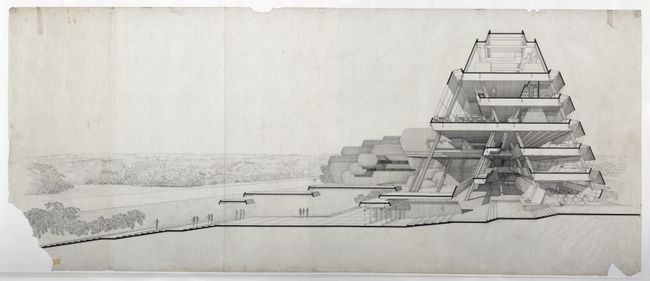

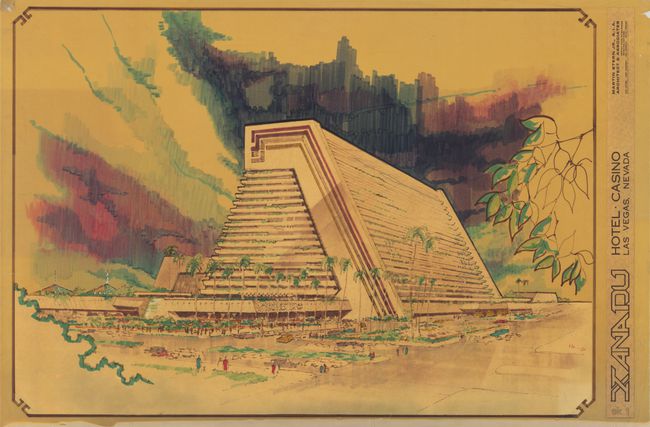

Paul Rudolph, Burroughs Wellcome & Company, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. Section perspective looking north, 1969–1972. Digital file courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Washington, D.C. © The Estate of Paul Rudolph, The Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation

- ER

- At the entrance to the exhibition, you make the unlikely link between Martin Stern Jr’s Xanadu project, and the Burroughs Wellcome by Paul Rudolph. Could you explain how this juxtaposition reinforces the logic of the exhibition?

- DH

- These two projects, shown one next to the other, are a perfect pairing. Architecturally, they are strikingly similar: planned around the same time, they have almost the same interior section and employ carpets that enhance the interior atmosphere. But they are also radically different: Rudolph’s project is in the tradition of the megastructure, while Stern Jr.’s is already deeply embedded in a world dictated by a capitalist way of thinking.

However, the pairing also marks the approach of the exhibition, which is to venture into new territories in order to flesh out the argument. Rudolph’s project is one of the highlights of brutalist architecture and a hallmark project in architectural circles—many architects have lamented its recent demolition. Martin Stern Jr., on the other hand, is the type of architect who operates on the fringes of so-called high architecture. So, he would usually be considered by design critics to be too commercial or to compromise the caliber of the profession. But projects such as The International (1969) or the Xanadu (ca. 1975, unbuilt) were prophetic both in their design and in the way they anticipated the extreme expressions of our current economy. Showing them in this exhibition is also a call to consider other forms of practice in order to understand fully, or more realistically, the context in which we as architects or historians, or both, operate. - ER

- If we step back and look at the exhibition as a whole, a question you are posing is who controls the carpet. Could you explain how you considered this question?

- DH

- The question of control is essential to this project in two ways: first, because it is often unclear who designed a carpet; and second, because if you accept the assumption that carpets perform in architecture—that they may serve functional and psychological aims—then who is in control of the contents of a building? How did it come to be that architects, including the most well-known and powerful ones, do not design what is sometimes the most dominant element in the space they produce? And if they do not control the carpet, then who does, and what are the motives behind its conception?

So, the exhibition proceeds with these questions, and since there is no single answer, it proposes four sections that present inconclusive versions of the story of carpets in buildings: the architect, the industry, the brand, and the user, each of which adds to a Rashomon-like narrative. - FG

- Why did you adopt such a narrative structure as analytical and investigative methodology?

- DH

- What I find so provocative about a Rashomon structure is that it allows for the coexistence of different perspectives that are basically incongruent. They’re not mutually exclusive and can both support and sometimes contradict each other. It also allows you to make certain links between different sections as part of a curatorial strategy, so you may see one thing that resembles or reflects what you’ve seen in another section.

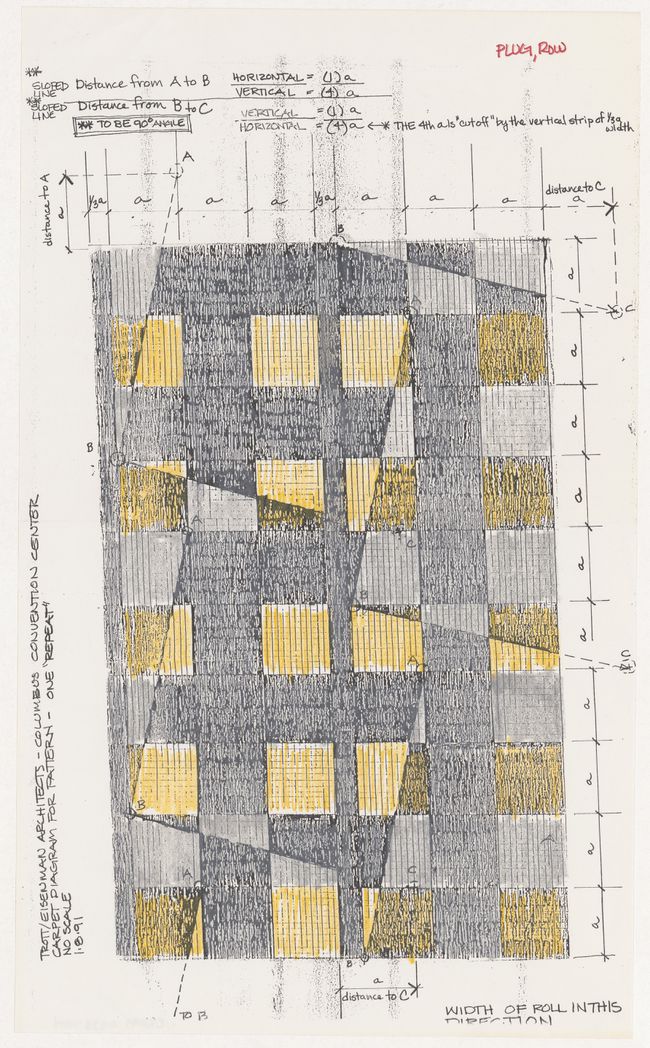

Eisenman/Trott Architects, Carpet design diagrams for the Greater Columbus Convention Center, Columbus, Ohio, 1990–1993. DR1999:0523:004, Peter Eisenman fonds, CCA

Inside Outside (Petra Blaisse with Simao Fereira, Marieke van den Heuvel, Mathias Lehner, Peter Niessen, Floris Schifferli), Plant-carpet design and photographs of the carpet scheme photographed by Iwan Baan for the Seattle Public Library, 2000–2005. © Inside Outside concept for Seattle Public Library. Photo © Iwan Baan

- ER

- The way these sections are developed in the gallery space seems to follow a clear narrative sequence.

- DH

- The first section you enter is that of the architect. It acts as a deception: while what the exhibition as a whole tries to show is that architects are not always in control, this first section in fact presents some cases in which architects actually did consider carpets seriously, such as in projects by Peter Eisenman or Petra Blaisse. But you soon realize that such cases are not typical as you move to the next sections: the industry ventures into the very different world of corporate designers; the brand looks to the rules and regulations that brands apply in controlling their retail spaces; and the user reflects on how user data and behaviour are used to optimize spaces for profit.

- ER

- Each section includes a short film commissioned and created by Ralitsa Doncheva. If the objects and exhibition prints are presented as clear evidence for each case study, these films somehow bring a more abstract and poetic narration, even a bit of anxiety, to each section, as they present objects that tell their secrets to the viewer.

- DH

- The short films act as a marker for each section, making each legible in relation to the others. The films are shown on separate screens, one of which lights up while the others await their turn, reinforcing that idea of a Rashomon structure as four distinct stories that coexist in the same space.

Doncheva created something that complements the materials shown in each section: the films are meditative sequences that lure you in through beauty and atmosphere, encouraging you to wonder and to explore, and reminding you that your way of looking at the subject is both analytical and atmospheric.

- ER

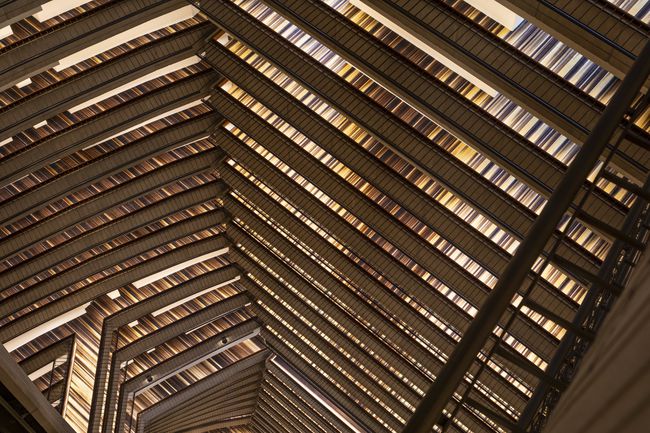

- All of these elements are surrounded by a series of photographs by the artist Assaf Evron, which present the carpet landscapes in John Portman’s hotels in the United States. They’re a key part of a collaborative research project between your and Evron. Could you speak about that?

- DH

- Many of the assumptions that led to this exhibition were originally discussed with Assaf. My first carpet experiences served as a basis for a photographic study he made of John Portman’s Hyatt O’Hare in Chicago, after which we knew there was something to be said about the relationship between the carpet and its host architecture. This independent inquiry developed into a Graham Foundation supported research trip, that lead us to some of the most extreme articulations of carpet spaces. And it was only when we spent a couple of days in these spaces—photographing, looking at the photographs, discussing the photographs—that we began to really understand what a carpet can do. The photographs included in the exhibition are therefore not documentary, but rather exploratory of a very specific effect the carpet generates in its environment, and how this environment is transformed by that effect, enhancing or neutralizing the original architectural intentions.

- FG

- The exhibition investigates North American case studies because they exemplify the development of a certain expression of capital embedded in Western discourse on space at a specific moment of time. Did you explore other case studies in other contexts?

- DH

- The exhibition begins with some projects from the 1960s, but it follows the evolution of an economic regime that is still in place today. So the fact that you can go to China and experience similar spaces is because the same companies, many of which were taking shape in the United States fifty years ago, are now operating around the globe. If you go to a conference in Shanghai or to a casino in Macau, you are likely to encounter brand standards and carpet designs that were conceived by the same experts and the same contracted companies.

But this is not to say that these spaces are the same everywhere—they are adapted and changed. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a very interesting experiment in that regard: for example, a place like Las Vegas depends on masses of visitors to generate the income that sustains its lavish interiors, carpets included. And it bounced back from the pandemic quickly; it was one of the first places to reopen because so much money is at stake. - FG

- It’s interesting that casinos and liquor stores, places that are driven by some sort of addiction and hyper-consumption, quickly reopened in the midst of the pandemic.

- DH

- I think that’s true. There is a lot to be said about how the owners of these places design their establishments to cater to psychological predispositions and to weaknesses. David Kranes, a leading casino consultant, told me that many casinos act like drug dealers: casinos abuse and “hook” their “users,” and “their lure is that of a one-night stand..” But beyond this particular industry, it is important for architecture to discuss the practice and potential of influencing psychology through design.

It is related to how we behave in virtual space, which is a space where we are constantly monitored, directed, and nudged to spend money. So perhaps the future of architecture is not in the parametrics of form but rather in the parameters of our mental landscapes.

- ER

- In the brand section of the exhibition, you present a case study that narrates the story of a specific carpet from a Marriott Marquis hotel in Atlanta, Georgia, whose pattern has been copied and disseminated. How does that relate with the brand theme?

- DH

- It all started with a photograph I came across, showing two men dressed as soldiers: they have toy guns in their hands, they’re crawling on the floor, and they’re camouflaged as the carpet. I recognized the carpet as that of the Marriott Marquis in Atlanta because it followed a John Portman design for the hotel floors. But the story of the carpet turned out to be even more hilarious than the photograph.

In 2013, Harrison Cricks, a prop designer and the owner of a company in the Esports industry (video game competitions), attended Dragon Con, a big convention that takes place annually at the Marriott Marquis. Since the carpet was the backdrop for the conference every year, Cricks designed the suits with the idea that these “soldiers” would blend in perfectly, which they did. Encouraged by the popularity of the pattern, he offered the suits for sale online, but was soon threatened with a lawsuit by the owner of the rights to the carpet, who argued that he was violating the intellectual rights of the brand by showing the design online.

- DH

- It turns out that brands such as Marriott own the rights to every designed element in their space. When Assaf Evron and I went to photograph these hotels, we had to sign copyright release forms because we were intending to show designs that were the property of the brand. These corporations developed very articulate ways to brand and control space through proprietary law.

However, it didn’t end there with the camouflage suits: other Dragon Con attendees started a group called Cult of the Marriott Carpet and made the carpet pattern available as an open-source file for members to print and produce items such as shirts and capes. They also developed a ceremony in which they bring pieces of the original carpet to the Marriott every year and recreate the carpet that is no longer there. So the carpet branded by Marriott was appropriated by convention participants and became a symbol of the place and of the Dragon Con spirit. In this case, the carpet and its meaning occupies a very unique position between the anonymous brand and the bottom-up organization of its devotees. - FG

- This example demonstrates and reveals how the discourse you are building reflects the evolution of the notion of space-making today—it reconnects with Martin Stern Jr.’s Xanadu project as the construction of an image more than of a building. The carpet, in turn, is used as a tool to develop an atmospheric branded notion of space. This is part of what makes corporate design so interesting today.

Carpets for Buildings (Marcel Kronenburg) in collaboration with Doepel Strijkers Architects, Rotterdam, Unrepeatable Carpet, carpet design for Holland Casino Amsterdam, 2008. © Carpets for Buildings

- DH

- The Dutch artist Marcel Kronenburg is very interesting in relation to such design. He developed a line of work—by his own account not always commercially successful—in which he collaborated with commercial flooring companies to create unique carpets for buildings, which is also the name of his company. And he would create these carpets based on an artistic approach that created a fusion with industrial technologies, and in the process challenged the capabilities of these companies.

For instance, when he designed a huge carpet for the municipality building of Schouwen Duiveland, a small town in the Netherlands, he proposed that the entire floor should be one uninterrupted surface made up of gradients of colour. Conceptually, he argued that this subtly changing uniformity represented the equal importance of bureaucrats and the townspeople they serve. But it became a technical challenge: he managed to digitally print the complex composition and in doing so he represents a carpet designer with a very unique ambition. - ER

- You use the term “deep space” in the exhibition. What do you mean by it in relation to architecture and to the specific case studies presented?

- DH

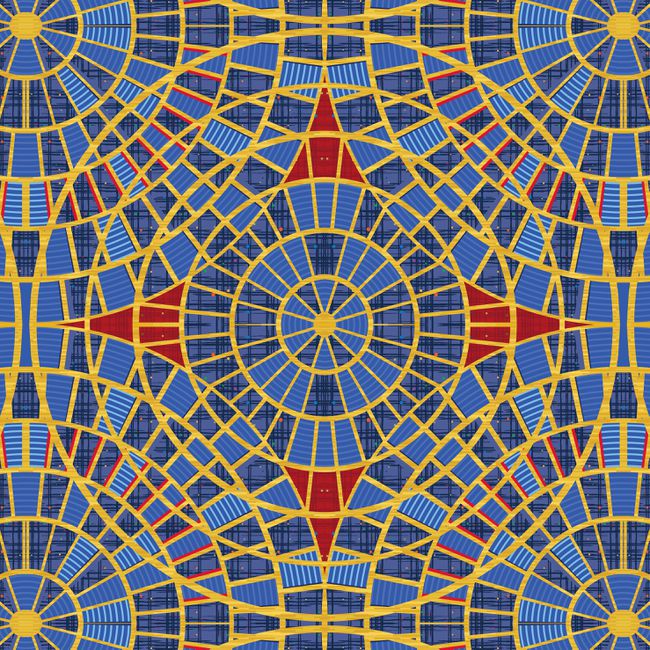

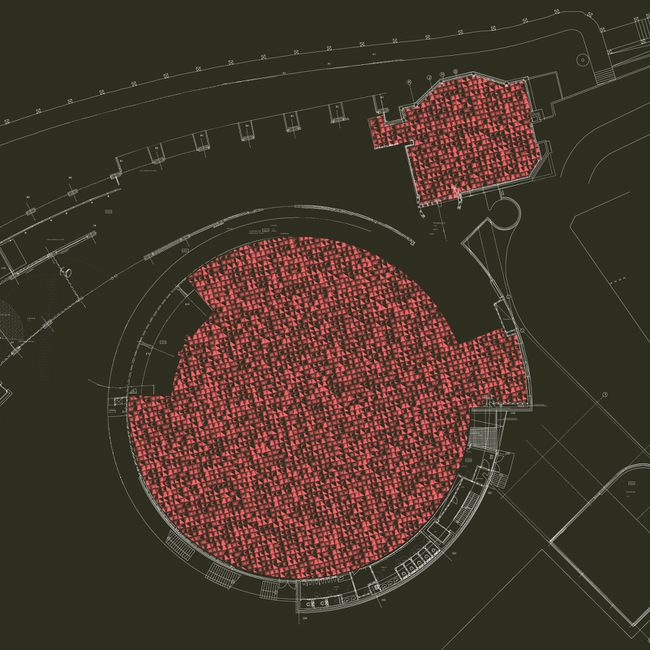

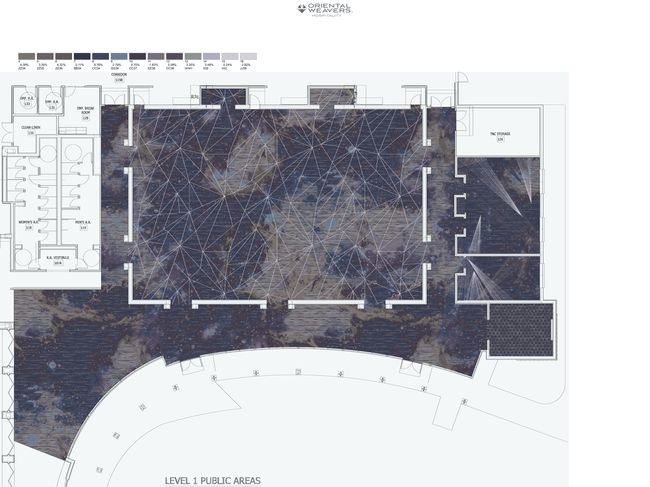

- I am referring to spaces that are large and complex enough to make you lose your spatial coordinates. Take the interior of a mega-resort for instance: it is a space in which the humanist conventions that have guided architecture since Leon Battista Alberti—perspective, directionality, orientation—no longer apply. Interestingly, deep spaces also led to a new way of describing, encoded through floodplans, which are the standard documents used by those in the flooring industry to communicate with interior designers and property owners. When executed with a high level of expertise, the floodplan can negotiate various viewpoints, capturing both the overarching design concept and the effects experienced in space. When you look at this representation of the carpet, you see both the galaxy that inspired the corporate designer and the world you enter as you walk upon the surface.

- ER

- You include a book by Bill Friedman in the User section. Why this book?

- DH

- In his astounding book Designing Casinos to Dominate the Competition: The Friedman International Standards of Casino Design, Bill Friedman, a recovered gambling addict and casino expert, specifies every imaginable element in casino design as a way to maximize profit. Friedman sees guests as automatons that can be easily manipulated by sensorial stimuli and psychological tactics. This control starts right at the entrance: “Just as the Pied Piper of Hamelin lured all the rats and the children to follow him,” Friedman writes, “a properly designed maze entices adult players.” In a chapter on the carpet, he argues that it is the most pervasive decoration in a casino and that it can either enhance the atmosphere or create a strong negative impression. His view of users as rats in a maze and of carpets as psychic manipulators became influential for decades, and only challenged in the last fifteen years by the design of more humane spaces.

In the gambling industry, spaces need to perform, meaning need to generate income, otherwise they are torn down and supplanted in an instant. In the carpet spaces we look at in this exhibition, extreme and lavish as they may be, architecture is understood to be always less eternal than money.

This interview was conducted in the framework of The Design of Carpets That Design Us