In Suspicion of Thresholds

Tairan An, Pinar Kutluay, Samuel Dubois

This is the third and final instalment of “In Suspicion of…”, a series of skeptical readings of the elastic intersections between law and the built environment, authored by the participants in the 2021 Toolkit for Today seminar on the theme of Legalities for Living and introduced by Shivani Shedde. Tairan An examines how nineteenth-century reclamation and improvement projects on the Neapolitan coast concealed subterranean ecosystems of sewage and waste, Pinar Kutluay analyzes how the facade negotiated Baron Haussmann’s urban reform principles based on order and uniformity, and Samuel Dubois explores how hacking practices enable Inuit to overcome municipal zoning by-laws and settler colonial approaches to territorial development.

In Suspicion of the Straight Line

Tairan An

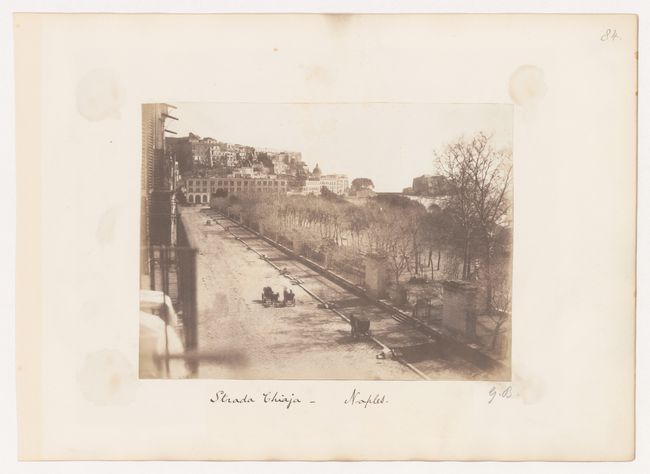

A scene captured by British photographer George Wilson Bridges in 1846 frames a slice of time out of the densely intertwined social, architectural, and environmental histories of the Villa Comunale park, which stretches along the Chiaia coast of Naples.1 The photograph stages a partitioned landscape in a narrow zone between the metropolis and the Mediterranean, demonstrating a set of meticulous linear demarcations separating residences, streets, plants, and water. Originally known as the “Villa Reale,” the park was begun in the 1780s at the Bourbon king’s behest as a royal promenade under the direction of architect Carlo Vanvitelli. Buildings, boulevards, curbstones, walkways, cast-iron fences, and juvenile roadside trees unswervingly align, as if cutting the borderland into even strips of space.

The word “shore,” similar to “shear,” “share,” or “sharp,” is derived from the proto-Indo-European root meaning “to cut”; perhaps not merely coincidentally, its Italian equivalent riva (as in riva del mare, or seashore) also originates from a notion of cutting and tearing. As a geographical reality that marks the division between landmasses and the sea, the shoreline magnifies the material operations that establish, reinforce, and clarify physical and symbolic spatial distinctions. From the curbs and the fences to the sidewalk and the road verge, these progressive architectural, managerial, and botanical interventions rendered the shoreline normal—in the sense suggested by Georges Canguilhem as involving the use of a T-square—to affirm human power over things.2 Issuing from the scientific regimens of land management informed by post-Enlightenment ideals such as rationality and objectivity, the linear territorial divisions evince a sophisticated system of control and containment carefully designed to conceal various impurities. For example, next to the city, which held a reputation as one of the most unhealthy in Europe, the Gulf of Naples had become a toxic soup created by a population dependent on inadequate water treatment facilities and cholera-infused shellfish.3 The aboveground, ordered features of the Chiaia coast camouflaged largely invisible contaminations below, which thrived in a techno-environmental complex of crooked and vascularized paths taken by animals, food, water, sewage, microbes, and human beings.

Two decades after the above photograph was taken, these contaminations and interconnections were laid bare. In 1872, German Darwinist Anton Dohrn founded the Zoological Station at Naples in the Villa Comunale park on the Chiaia coast. Although it soon became one of the most prestigious institutes for biological research in Europe, this station was an anomaly. Unlike the many so-called biological field stations established during the late nineteenth century in remote locations to facilitate the observation of organisms within their natural environments, economic realities required that Dohrn’s station be set in a seaport to serve simultaneously as a public aquarium.4 As a result, the station did not bring zoologists closer to the “pure” living nature of sea creatures as Dohrn had envisioned, but to a metropolis surrounded by seawater heavily polluted by the city’s notoriously decrepit sewage system; the quality of the water was so undesirable that it had to be thoroughly filtered before it could be used in laboratory tanks.5

The Zoological Station literally sat at the intersection of the aboveground partitioned landscape and the subterranean crooked paths. As a public aquarium designed in the fashionable neo-classical style of its time, it aligned with reclamation and improvement projects of the Chiaia coast begun in the late eighteenth century. As an institute for animal research, it invites a suspicious reading of its own conformity with these spatial linearities, as it simultaneously engaged and disclosed a hydro-social ecology that disrupted architectural and territorial ordering. As demonstrated by the basement floor plan, a main trunk of the municipal sewer cut right across the building, discharging wastewater from both the city and the laboratories into the gulf. In other words, the attempts to maintain an unadulterated, “natural” milieu for marine organisms entangled the station within a techno-natural assemblage that was embedded, if uncharted, in the urban landscape.

-

On the reclamation and improvement of the Chiaia coast and the Villa Comunale park, see Ornella Cirillo, “Il Real Passeggio di Chiaia,” in Carlo Vanvitelli: architettura e città nella seconda metà del Settecento (Firenze: Alinea Editrice, 2008), 39–62. ↩

-

Georges Canguilhem, The Normal and the Pathological, trans. Carolyn Fawcett (New York: Zone Books, 1989), 125. ↩

-

For a history of the sewage system in Naples, see Ettore d’Elia, “Sulle origini storiche e sull’evoluzione della fognatura di Napoli,” L’Acqua (2015) (6): 19–41. ↩

-

On the architectural analysis of the Zoological Station at Naples, see Riccardo Florio, L’Architettura delle idee. La Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn di Napoli (Napoli: Artstudiopaparo, 2015). ↩

-

See Raf De Bont, Stations in the Field: A History of Place-Based Animal Research, 1870–1930 (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2015), 59; Charles Atwood Kofoid, The Biological Stations of Europe (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1910), 31. ↩

In Suspicion of Order

Pinar Kutluay

In the nineteenth century, Paris underwent a historic urban redesign founded on principles of spatial order and regulation that significantly changed its layout. Baron von Haussmann, a civic official with close ties to Emperor Napoleon III, supervised and implemented these interventions. With his support, Napoleon III accelerated the urban reformation that was initiated by the previous administration. To develop the city across spatial and social levels and attract investors, Napoleon III introduced tax exemptions that prioritized transformations according to notions of circulation, health, and security.1 While Haussmann’s design ideas primarily focused on improving and regularizing the urban fabric of Paris, his urban redesign also had a remarkable impact on architecture through the design of facades. Based on a visual analysis of a photograph by Achille Quinet from the 1870s, the following text explores how Haussmann’s urban planning regulations transformed the building facade as a threshold of order that puts into suspicion the establishment of uniform architectural standards.

Napoleon III initiated urban improvement projects from the beginning of his presidency in 1848. He replaced the prefect of Paris, Jean-Jacques Berger, who “opposed on principle the idea of taking up loans to extend the improvement program,” with Haussmann.2 At that time, Paris’ urban fabric comprised a heterogeneous, independent mass of houses that lacked any discernible stylistic connection. Narrow streets and crowding exacerbated poor hygiene and spatial environments that supported violent and harmful activities.3 In addition to improving public planning and health, Napoleon III appointed Haussmann to develop an urban reform project for military purposes, largely to prevent rioting by expanding city streets and organizing the urban centre through wide, intersecting boulevards.4

Apart from its urban focus, Haussmann’s plan influenced architectural design, especially the design of façades. Under Haussmanization, buildings were built according to strict and simple design standards to prioritize stylistic coherence across the grand boulevards. As seen in the photograph by Quinet, after the implementation of Hausmann’s project, the windows of two adjacent buildings in Paris became almost identical in size. The designs of the two façades are not the same, but their massing and composition are proportionally similar, lending a sense of uniformity and order to the streetscape. In this sense, their designs align with Napoleon III’s urban reform principles. Haussmann used the term “regularization” to describe and justify his proposal to transform Paris. His urban regularization project could be understood as a “form of critical planning whose explicit purpose is to regularize the disordered city, to disclose its new order by means of a pure, schematic layout which will disentangle it from its dross, the sediment of past and present failures”.5 Under his lead, the city witnessed many changes to its pre-modern fabric. For example, workers’ neighbourhoods were targeted as areas prone to civic rebellion and violence; their houses were thus demolished, and they were sent to the periphery of the city and told to come back when the new buildings were ready. However, when they returned, they unfortunately faced the problem of rent increase and had been priced out of their former neighbourhoods.6

The façade is the architectural element that most directly relates buildings to their urban environments, like an expressive face oriented outward. In the case of nineteenth-century Paris, it inevitably became a part of the urban scene and the implementation of Hausmann’s regulations for his urban plan. Serving as a threshold of order between urban and domestic realms, the facade’s design also indexed broader social concerns. It was cheaper to implement such standardized designs in the nineteenth century, which benefited the mass of middle class residents in need of affordable housing at the turn of the century. However, by making Hausmann’s regulations on urban order and uniformity visible on the surface of the building, the façade also suppressed the politics involved in displacing working classes and effacing the past.

-

Barry Bergdoll, European Architecture 1750–1890 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 241. ↩

-

Thomas Hall, Planning Europe’s Capital Cities, Aspects of Nineteenth-Century Urban Development (London: E&FN Spon, 1999), 65. ↩

-

Hall, Planning Europe’s Capital Cities, 81. ↩

-

Leonardo Benevolo, History of Architecture, vol.1 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1980), 67. ↩

-

Françoise Choay, The Modern City: Planning in the 19th Century (New York: George Braziller, 1969), 15. ↩

-

Michael Adcock, “Remaking Urban Space,” University of Melbourne Library Journal 2, no. 2 (1996): 25–35. ↩

In Suspicion of Zoning By-Laws

Samuel Dubois

Published in 2019 and supported by the CCA, Blueprint for a Hack: Leveraging Informal Building Practices documents the 2017 “Kuujjuaq Hackathon.” This original event brought together Inuit from Kuujjuaq, Québec and design students and professionals from southern Canada with one common objective: to reimagine the underused public spaces of Kuujjuaq through the creative repurposing of materials from the municipal dump. At the core of this project was the notion of hacking—the recycling and upcycling of disused materials and other defunct technologies through DIY methods. Embedded in the rich informal building culture of the Inuit, hacking practices are often seen as a response to the “institutionalized inadequacy” of postwar architecture in the Canadian North.

One of the intended goals of Blueprint for a Hack is to highlight “critical elements of a successful hacking methodology that can inform future planning and design practices.”1 Yet in most municipalities in Canada’s northern regions, hacking methodologies and legal realities are fundamentally irreconcilable. This is due to zoning by-laws, which enable municipal authorities to control and regulate the use of land by organizing it into “zones.” Blueprint for a Hack briefly addresses this issue in its introduction: “For the once nomadic Nunavik Inuit, the concept of boundaries, much less the administrative or legal kind, is a vague curiosity. Still, the municipal system forced them to mark their territory, defining orientations and land use with an alien logic of spatial division.”2 In other words, zoning by-laws are profoundly antithetical to the Inuit worldview, whereby land, nature, and its resources are sacred and must be revered. The imposition of municipal zoning by-laws to control Inuit communities in the Canadian North is thus conceptually analogous to the control exerted over other First Nation groups by the reserve system. In both cases, this form of land-based control is the result of colonization.

Drawing from Canadian scholar Shiri Pasternak’s framing of land property as a “technique of jurisdiction,” this text emphasizes a more comprehensive understanding of how municipal systems in Canada generally impede Inuit engagement in hacking practices.3 While it is crucial to showcase the relevance of this methodology in the success of the 2017 Kuujjuaq Hackathon, it is equally important to be in suspicion of zoning by-laws and other legal imperatives that would typically prevent similar community-led design endeavours from being initiated in other villages in the Canadian North.4 Without the support of the municipality of Kuujjuaq and the institutional exposure enabled by the Hackathon, one may wonder how easy or not it is for Inuit to engage in informal building practices such as hacking around their homes in northern regions.5

In Kuujjuaq, for instance, municipal zoning bylaws allow accessory buildings or structures to be erected in any zone, with some conditions related to size, setback, and signage.6 Other villages in the Canadian Eastern Arctic, such as the small hamlet of Qikiqtarjuaq in Nunavut, also permit accessory buildings or structures in any zone but with more restrictive regulations. Following the town’s bylaws, Qikiqtarjuaq’s residents are not allowed to keep “any object or chattel which, in the opinion of the Development Officer, is unsightly” in any yards located in residential zones.7 Here, the subjective nature of what is considered “unsightly” or not mirrors the broader elasticity of municipal legalities vis-à-vis the construction of structures through informal hacking practices. Whether in Kuujjuaq, Qikiqtarjuaq, or other Canadian towns, zoning regulations fundamentally operate in the same way. They are based on jurisdictional techniques, to use Pasternak’s terms, derived from settler colonial attitudes to land control, whereby territorial development depends on the imposition of restrictions that conceive of land as property.

To understand how zoning by-laws oppose the realization of informal building practices and, more broadly, Inuit ontologies regarding land, one must question the legal assumptions that structure how, by whom, and under what conditions hacking can be undertaken in the Canadian North. Nevertheless, it is equally important to examine, understand, and document the historically perverse effects of zoning by-laws on Inuit polity to inform a more comprehensive path forward for future planning and design practices in Canada’s northernmost regions.

-

Susane Havelka, Vikram Bhatt and Dave Harlander, Blueprint for a Hack: Leveraging Informal Building Practices(New York: Actar Publishers, 2020), 19. ↩

-

Havelka, Bhatt, and Harlander, Blueprint for a Hack, 17. ↩

-

Shiri Pasternak “Property as a Technique of Jurisdiction: Traplines and Tenure,” in Contested Property Claims: What Disagreement Tells Us about Ownership, ed. Maja Hojer Bruun, Patrick J.L. Cockburn, Bjarke Skaerlund Risager, and Mikkel Thorup (Milton Park: Routledge, 2017), 166–184. ↩

-

The Hackathon’s three driving objectives were to improve the public realm, reduce landfill waste, and provide cultural exchange opportunities. ↩

-

The Kuujjuaq Hackathon was supported by the CCA, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), and McGill University Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture. ↩

-

Northern Village of Kuujjuaq, Kuujjuaq Zoning By-Law, Council of the Northern Village of Kuujjuaq. By-Law No. 2017-02 (Kuujjuaq QC: Northern Village of Kuujjuaq, June 2017), 11. ↩

-

Municipality of Qikiqtarjuaq, Qikiqtarjuaq Zoning By-Law, Council of the Hamlet of Qikiqtarjuaq. By-Law 244 (Qikiqtarjuaq, NT: Municipality of Qikiqtarjuaq, March 2015), 26. ↩