Upon opening their Winnipeg office around 1965, the van Ginkels became enmeshed in the Canadian resource economy. Projects assumed infinite scope. Things began to reach far beyond the city or the landscape to the size of the country itself. The outlook kept faith with Progressive Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s “Roads to Resources” program initiated some years earlier (and nurtured over the ensuing long Liberal reign coinciding with the van Ginkels’ professional life). “As far as the Arctic is concerned, how many of you here knew the pioneers in Western Canada,” Diefenbaker had asked during his 1958 election campaign.

I saw the early days here. Here in Winnipeg in 1903, when the vast movement was taking place into the Western plains, they had imagination. There is a new imagination now. The Arctic. We intend to carry out the legislative programme of Arctic research, to develop Arctic routes, to develop those vast hidden resources the last few years have revealed. Plans to improve the St Lawrence and the Hudson Bay route. Plans to increase self-government in the Yukon and Northwest Territories. We can see one or two provinces there.

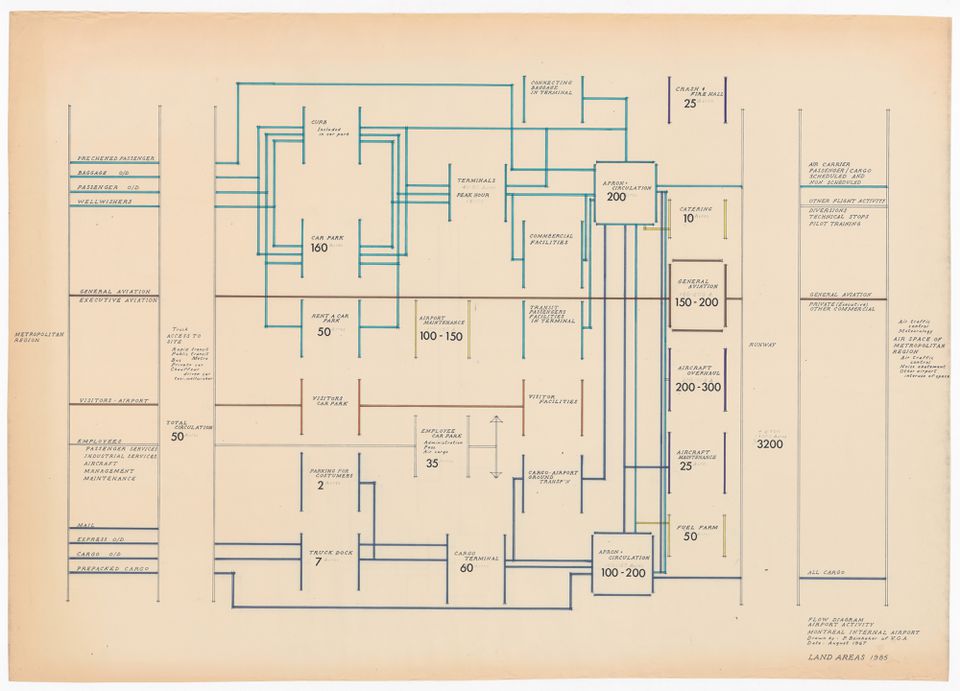

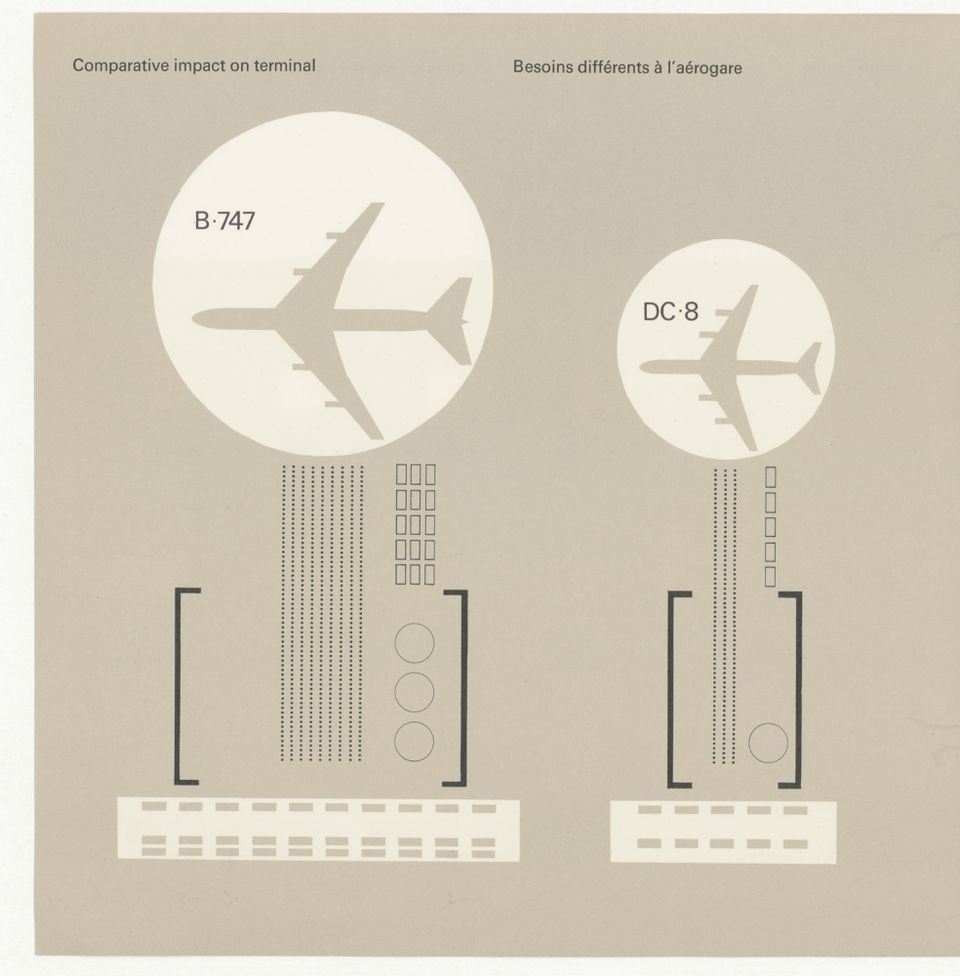

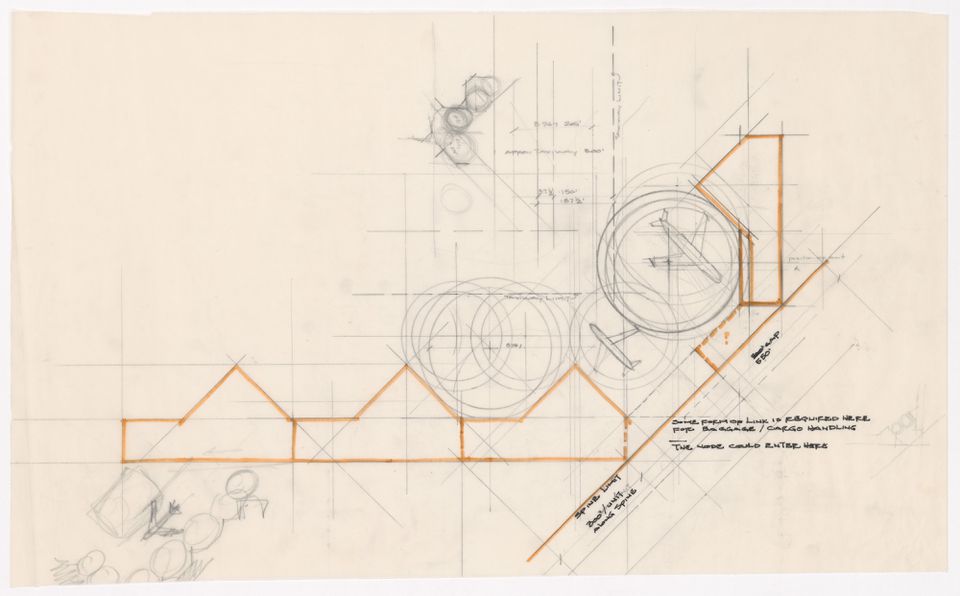

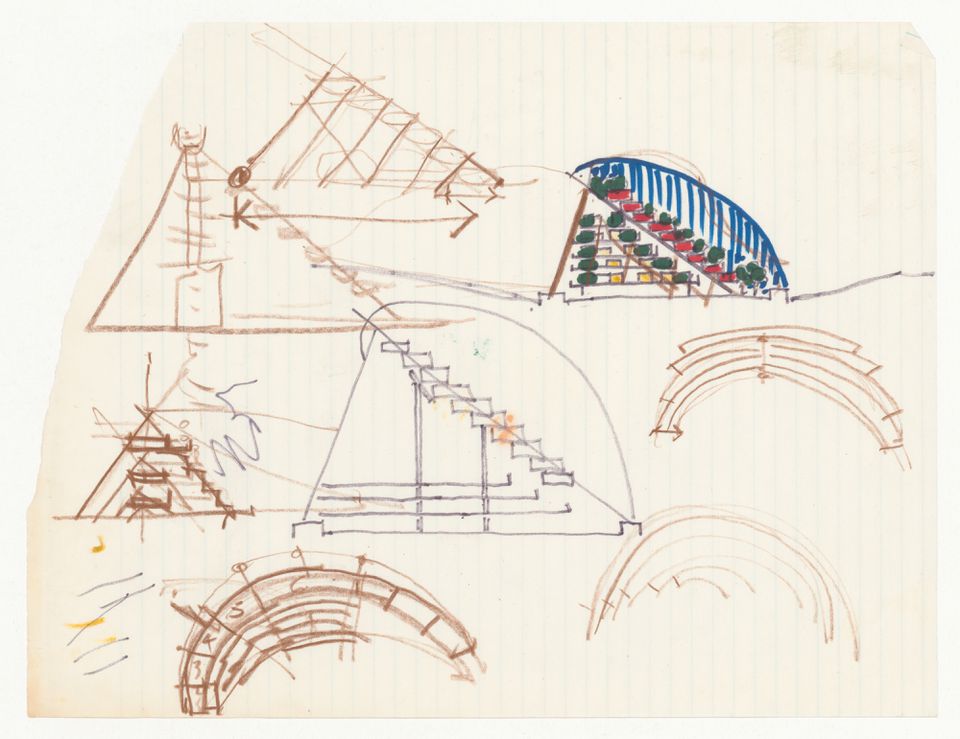

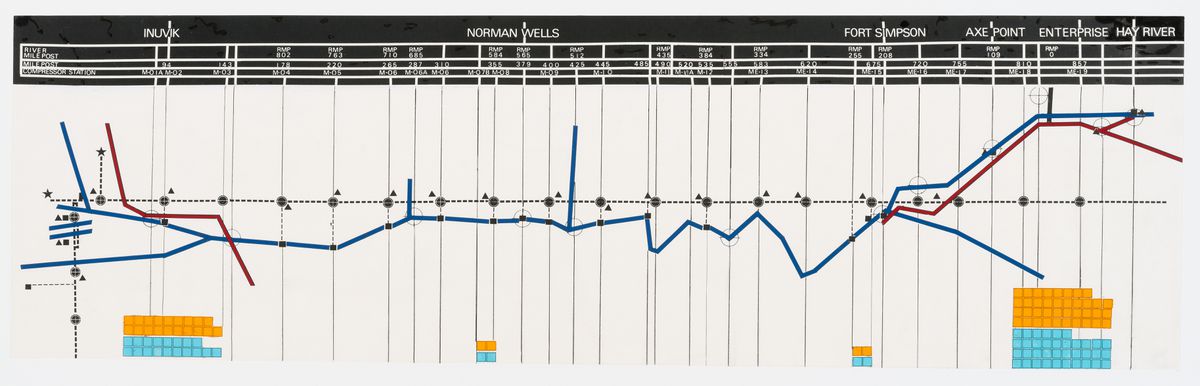

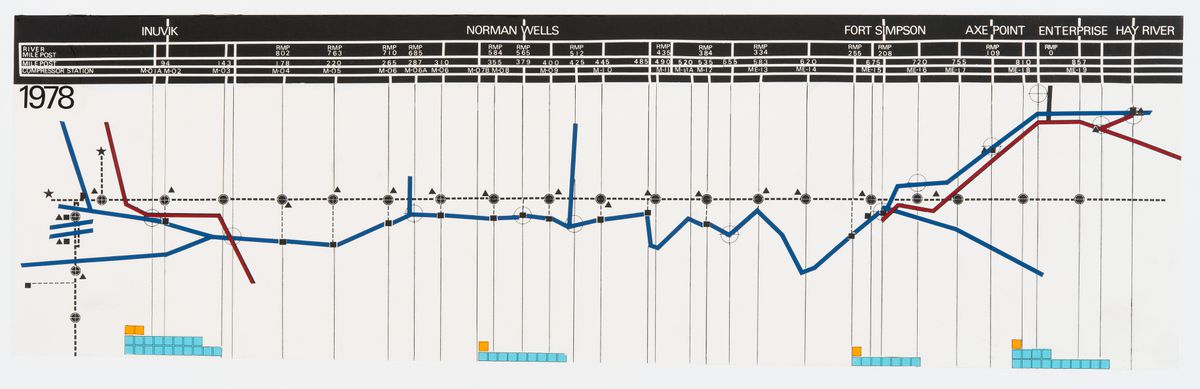

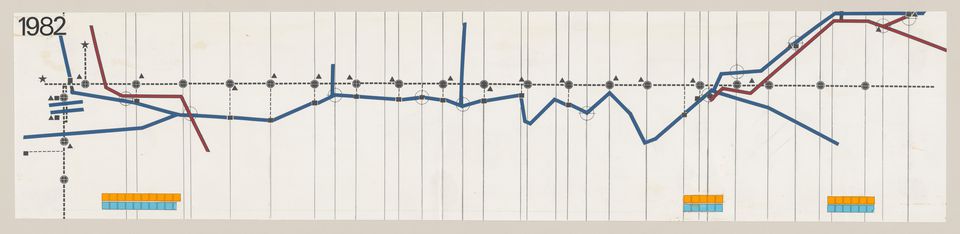

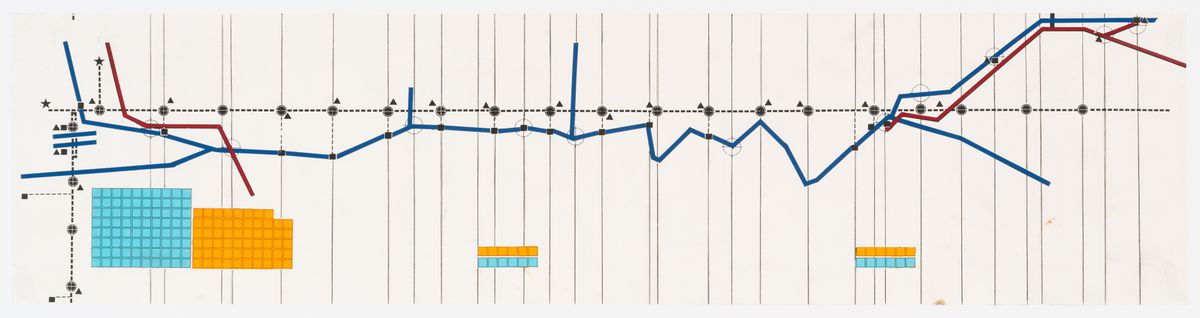

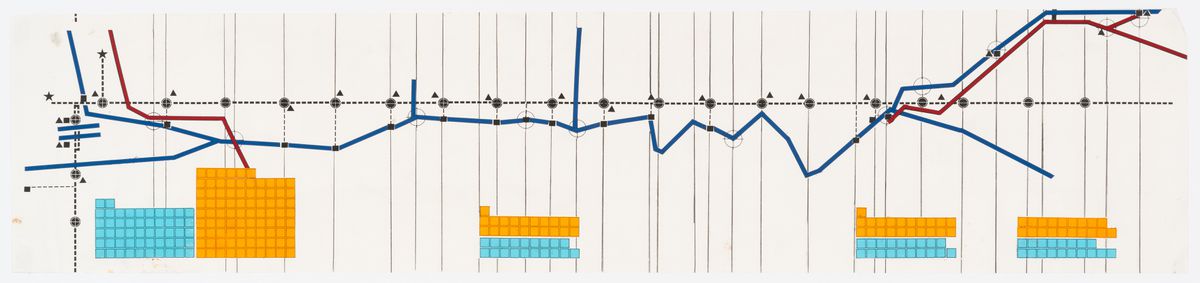

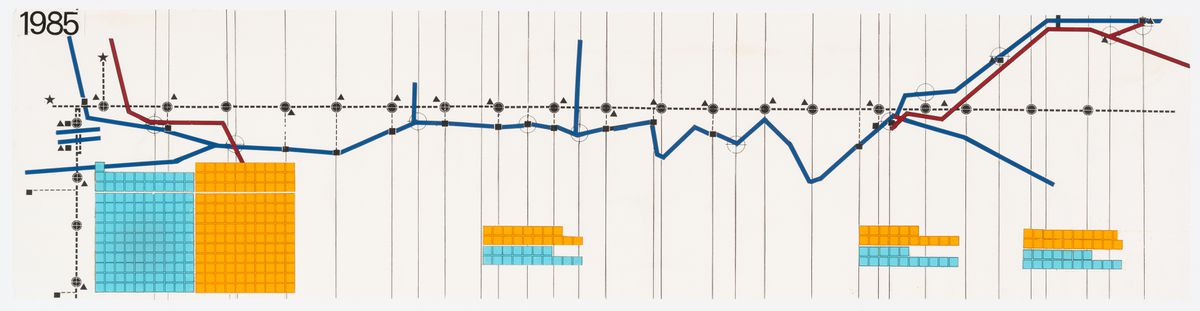

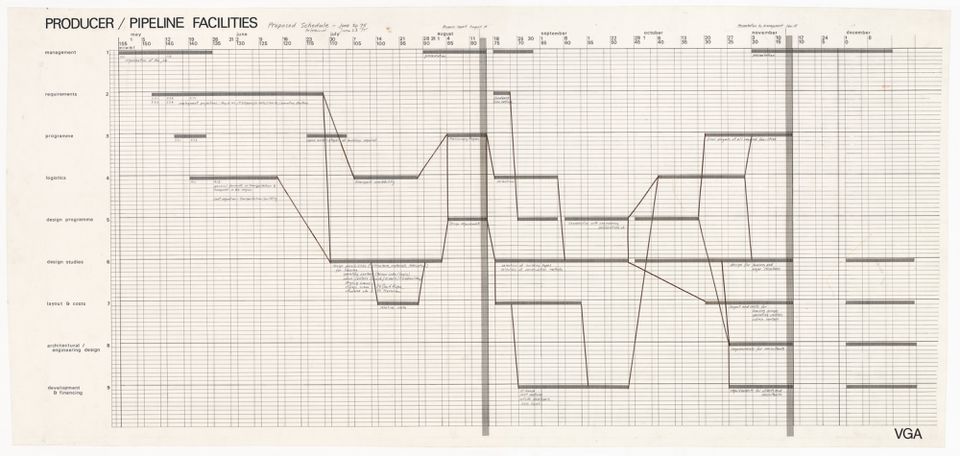

The van Ginkels turned their attention northward. Potash extraction in Esterhazy, Saskatchewan. Pipelines along the Mackenzie River valley. Nuclear-powered submarines ferrying oil via circumpolar routes. Their studies provided powers-that-be with promises of national rejuvenation.

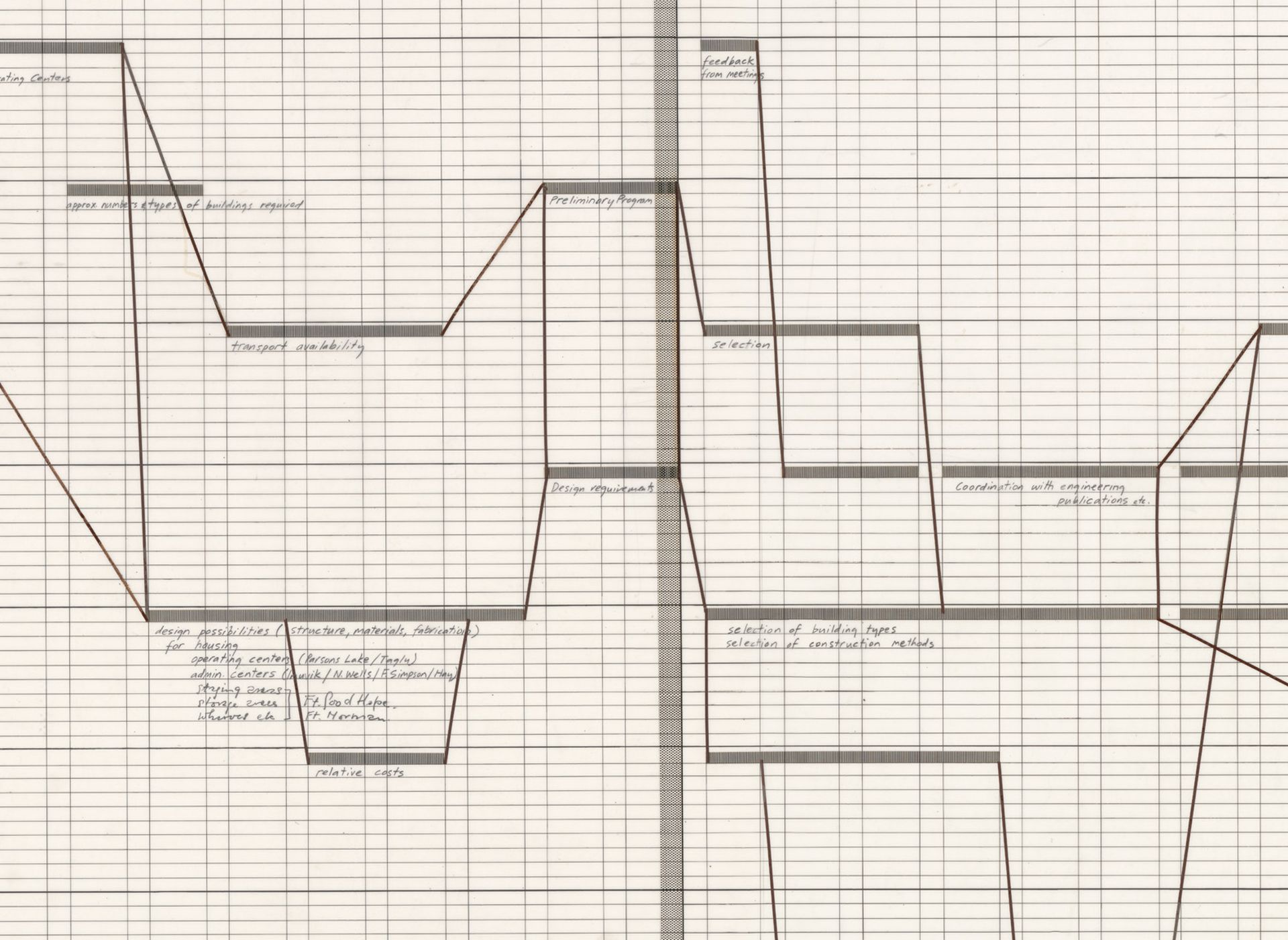

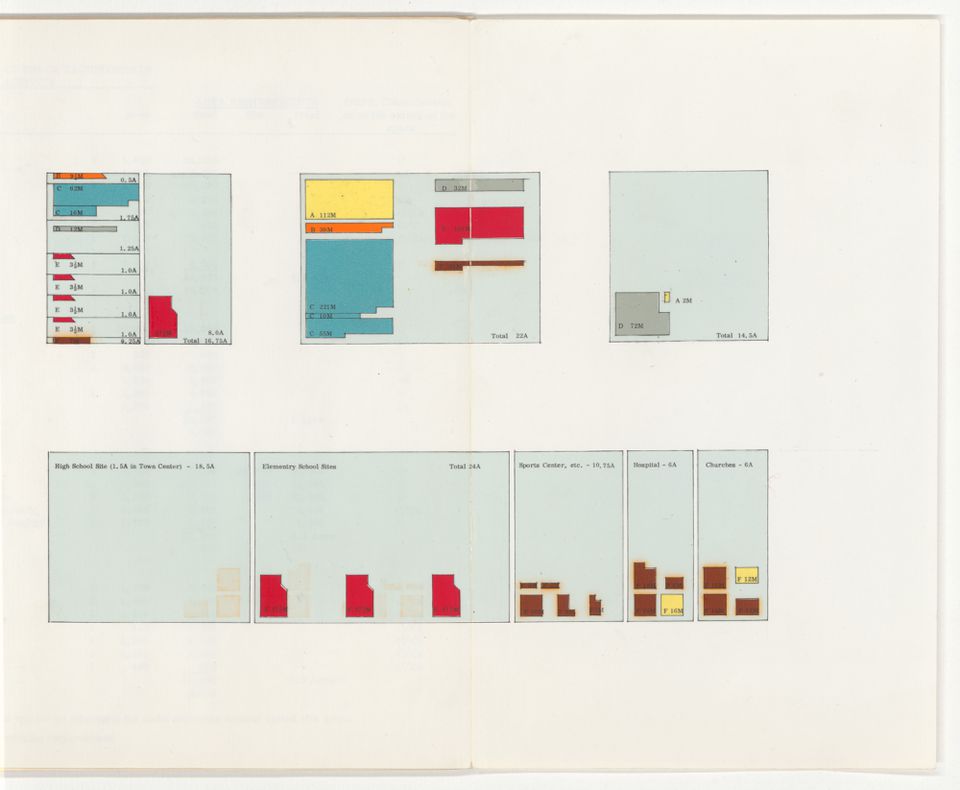

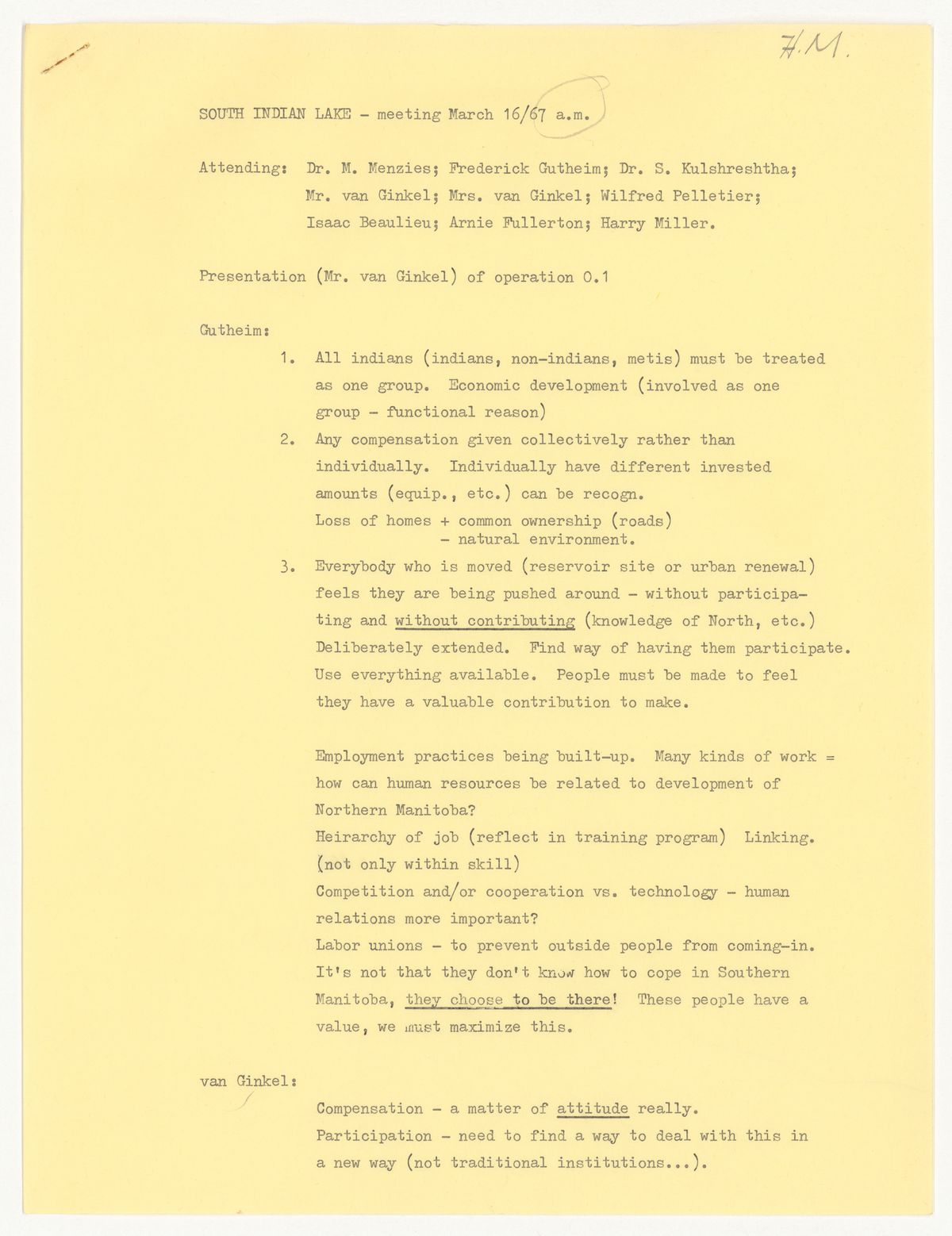

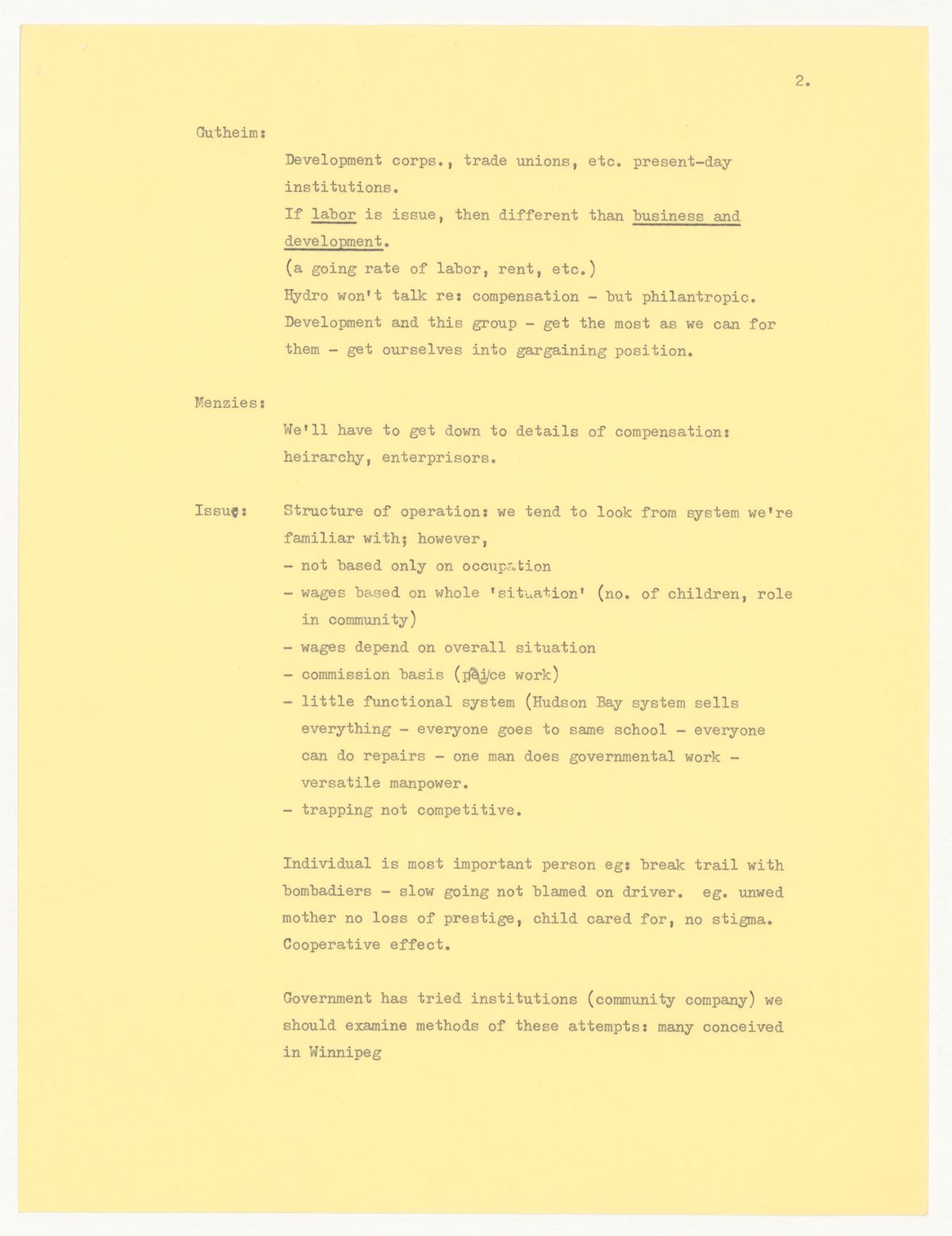

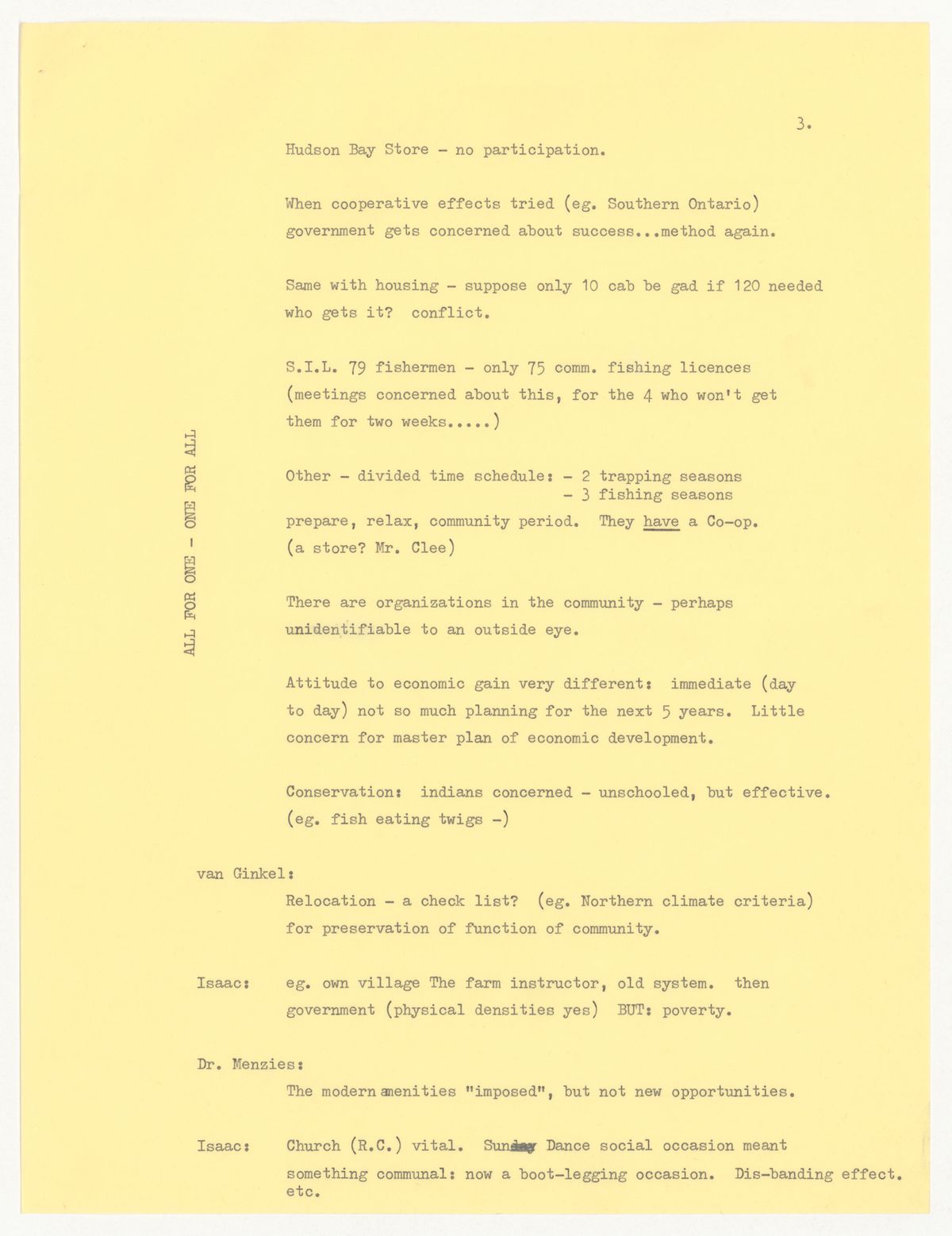

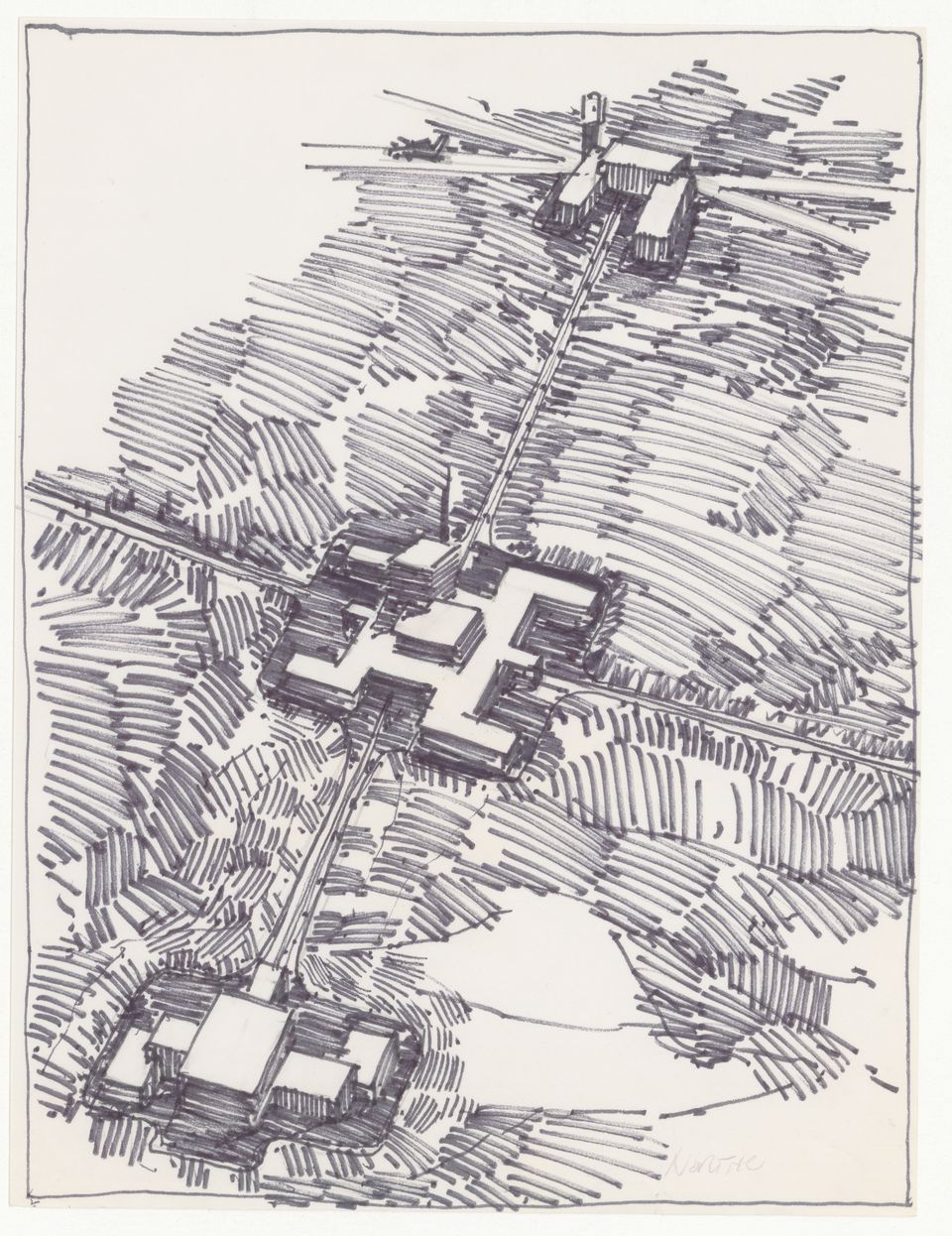

In 1966 the van Ginkels addressed the relocation of communities in South Indian Lake, Manitoba, facing the damming of the Churchill River. Change was afoot, and skilled jobs would become plentiful. Even as they sympathised with “Indians” destined to lose traditional ways of life, the van Ginkels saw the abandoning of trap lines for industrial trades as intrinsic to modernization (in meeting minutes, they recognized but rarely lamented the relocation of children to residential schools). A decade later, when studying northern settlements, the van Ginkels may have undergone a change a heart. Rather than new towns, they recommended a continuous airlift of people and material. Fly teachers to Inuit communities, the van Ginkels reasoned, instead of sending children to southern schools. For an instant a network of commerce and infrastructure offered a potentially humane solution to crises of forcible assimilation and cultural impoverishment. The moment passed. The needs of Inuit, First Nations, and Métis (all earning, the van Ginkels noted, fractions of the income earned by “Whites”) mattered little in the great game of development. The van Ginkels, like so many architects and bureaucrats (good modernists all) understood the North not as terra incognita, unknown and unmapped, but as terra nullius, a realm where Indigenous Peoples existed but without title or sovereignty.