How to Access Digital Files from the Nineties

A Case Study by Tessa Walsh

Step 2: Connect the drive to BitCurator1 using a hardware write blocker2 to prevent any unintentional changes to the disk.

-

The BitCurator Environment is a suite of free and open-source digital forensics tools and software. BitCurator was created at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill specifically for use by collecting institutions, and is now maintained by the non-profit organization BitCurator Consortium, of which the CCA is a member. ↩

-

Write blockers are devices that allow users to interact with and acquire data from digital storage media without altering their contents (i.e., files and file system metadata such as the dates files were last modified). ↩

Make a bit-by-bit disk image1 of the drive.

-

A disk image is a digital file that perfectly replicates the content and structure of a physical storage medium such as a hard drive or floppy disk. Disk images retain all qualities of the original media in a software form that is easier to interact with and preserve over the long term. ↩

Step 3: Analyze the disk image.

(In this case, an HFS-formatted disk1 indicates that the files originate from a Mac.)

-

Storage media such as hard drives and floppy disks use file systems to keep track of files and their key metadata (dates, file type, permissions, and so on). Hierarchical File System (HFS) is a proprietary file system used by Apple on their “Classic” Mac OS–era devices. ↩

Step 4: Characterize the disk image and extract files.

(For raw disk images of HFS-formatted disks, we can use HFSExplorer,1 either by itself or from within Brunnhilde.2)

-

HFSExplorer is an application that can read and export files from Mac-formatted storage media, including those using the HFS file system. ↩

-

Brunnhilde is a free and open-source characterization tool for directories and disk images that produces human- and machine-readable reports to assist in the triage and description of digital archives. ↩

Step 6: Figure out how to work with it.

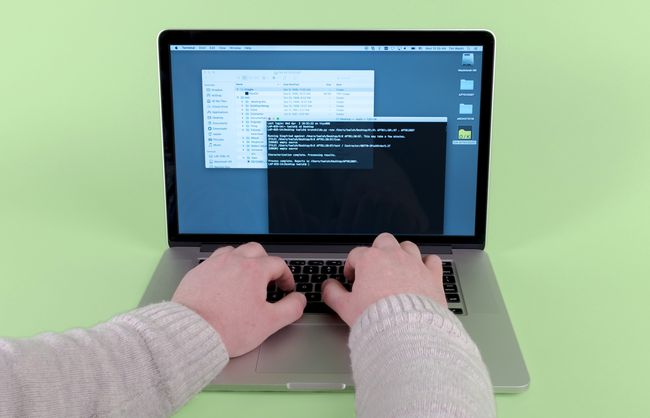

(In this case, we should check whether switching to a modern Mac helps us identify and work with these Mac-originating files. It seems likely that the .sea files are some sort of archive file.1 We can see if the command-line2 version of The Unarchiver3 knows what to do with them.)

-

An archive file is a digital file comprised of one or more digital files bundled together for portability and storage. Archive files are often but not always compressed. ↩

-

Command-line utilities are programs that do not have graphical interfaces (i.e., windows with buttons). Instead, users interact with command-line utilities by issuing commands as text in a terminal. ↩

-

The Unarchiver is an archive un-packaging program for Mac designed to handle more archive file formats than can be natively handled by macOS, with both graphical and command-line interfaces. ↩

Repeat step 5: Look at the results and determine what you have.

(The .sea files are archive files—StuffIt Expander Archives,1 to be precise. Our Mac recognizes some files within these packages as older Word documents and leaves others unidentified.)

-

StuffIt Expander is a proprietary archive utility with the ability to create “self-extracting archive” files, which theoretically can unpack themselves without any software necessary. StuffIt was extremely popular in the 1990s. Despite the promise of the name, “self-expanding archives” are not always able of unpacking themselves on modern computers without the assistance of additional software. ↩

Repeat step 6: Figure out how to work with it.

(We can use Siegfried1 to identify the precise file format and version of the file in question.)

-

Siegfried is a free and open-source signature-based file format identification tool. “Signature-based” means that Siegfried identifies files by comparing parts of the file’s code against known signatures collected in format registry databases rather than relying on the file’s (arbitrary and sometimes inaccurate) extension. ↩

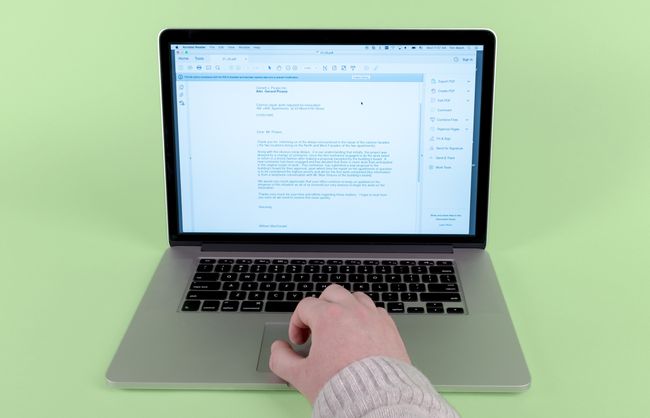

(Our file is a ClarisWorks word processing file! Maybe Word will know what to do with it… Hmm. We’re getting there, but what is with the weird formatting? Maybe LibreOffice1 can do a better job of rendering the file.)

-

LibreOffice is a free and open-source office suite forked from OpenOffice and maintained by the Document Foundation. LibreOffice is capable of reading files created in a number of obsolete and/or niche word processing formats. ↩

Step 7: Scale your operation.

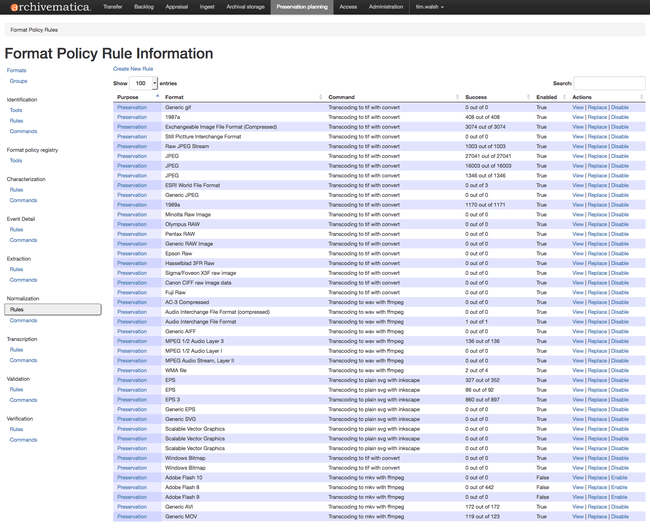

(If we want to enact this type of digital archaeology or digital preservation at larger scales—say, every file in that SEA package, or in every SEA package on that disk, or in that archive, or in the whole of the CCA Collection—we need to automate processes where we can. Luckily, we can use scripts and digital preservation software like Archivematica1 to handle tasks such as format identification, characterization, and normalization of the most common formats in batches, allowing us to spend our time on the difficult and interesting cases.)

-

Archivematica is a free and open-source digital preservation system that manages the characterization, packaging, storage, monitoring, and retrieval of digital files in large-scale digital archives. A number of institutions besides CCA use Archivematica, including MIT Libraries, Tate, and the Museum of Modern Art. ↩

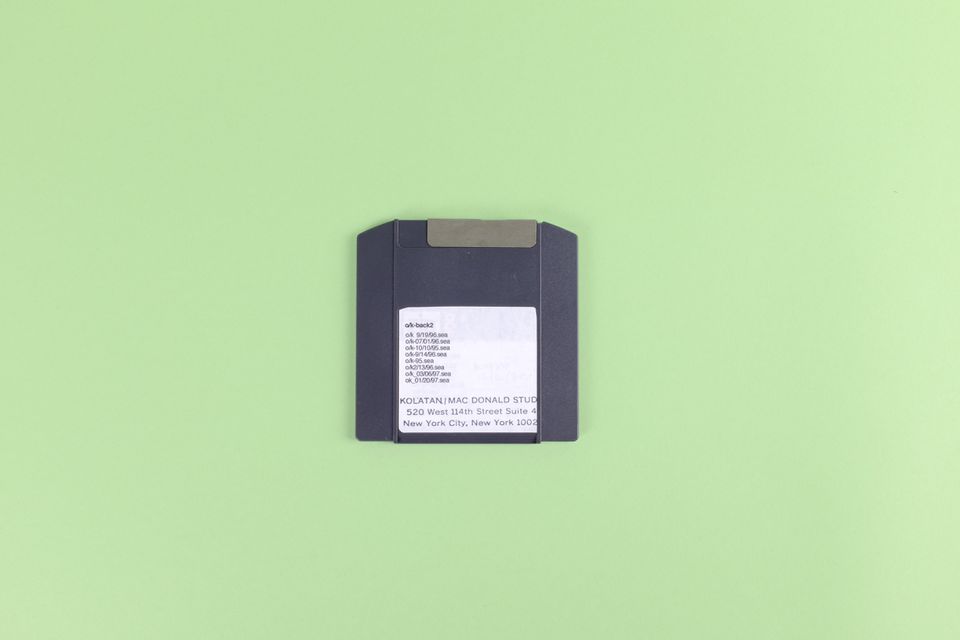

This Zip disk is part of the KOL/MAC Project Records.