On the Edge

Davide Deriu on photography and the vertigo of modern architecture

Protective barriers are ubiquitous features of our built environment, yet they often remain unnoticed. Architectural elements such as handrails and parapets reflect the building codes in force at a particular place and time; their wide-ranging variations in shape, size, and materiality visually and physically manifest the regulatory frameworks that aim to safeguard users from accidents. In the early twentieth century, however, roof terraces and projecting balconies expressed a desire to defy gravity, as epitomized by the low parapets and horizontal rails of modernist housing. Although safety barriers mostly retained their original purpose of preventing people from falling, they were increasingly designed to allow visual continuity with the space beyond the edge, thereby challenging the user’s sense of balance.

The photo essay addresses a range of material and perceptual tensions inherent to safety barriers by weaving together a series of images from the CCA collection dating from the 1920s to the 1950s.1 Revisiting some prominent places in the canon of Western architectural history, it explores how photographs can allow us to visualize the tense state of being on the edge—that liminal space that brings us in contact with the abyss. A historical-critical approach combines with a speculative impulse driven by a subjective response to images and the spaces they depict. The latter is driven by a focus on the punctum of each photograph: the particular detail that “shoots out of it like an arrow”, awakening sudden associations and recollections.2 The effect of pricking the viewer, which bears on the intensity of time, can tear through the present with unexpected force.

The selected images foreground the issue of height vertigo, a visceral and ambivalent sensation that is associated with a wide spectrum of emotions, ranging from thrill to anxiety.3 How can we reclaim the narrative potential of architectural photographs, a particular category of images in which buildings and spaces usually dominate over people and experiences? The texts below each image might tentatively be called “photo legends”. As opposed to the caption, which claims to seize hold of an image and fix its meaning once and for all, the term “legend” opens an alternative realm of interpretation. If we turn to French or Spanish, where the words for “caption” are respectively légende and leyenda, we can envisage another way of reading photographs, one that leaves space for stories and myths.

The essay draws on the indeterminate character of fragments to offer a series of threads that readers can pick up to weave different observations or interpretive directions. Disrupting the logic of the archive, it kindles a new way of looking at these images by highlighting an often-neglected aspect of modern architecture: its edge condition in which fear and exhilaration collide, provoking tiny sparks of illumination.

-

This essay draws and expands upon research conducted at the CCA during the Multidisciplinary Research Program, Architecture and/for Photography, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (2016–2017). ↩

-

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (London: Vintage, 1980), 26. ↩

-

Davide Deriu, On Balance: Architecture and Vertigo (London: Lund Humphries, 2023). ↩

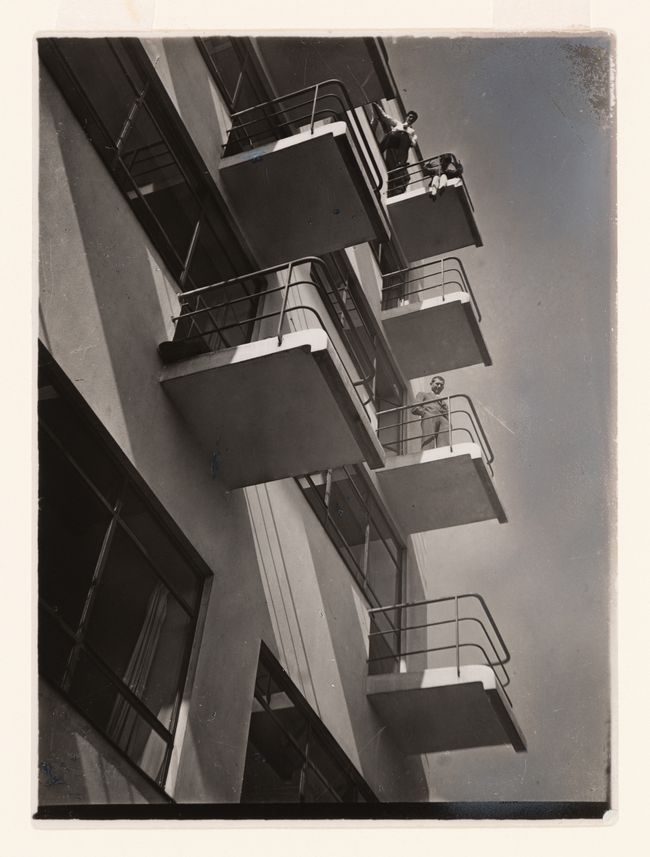

László Moholy-Nagy’s portrait of Marcel Breuer on a studio balcony epitomizes the convergence between the avant-gardes of Neues Sehen [New Vision] and Neues Bauen [New Building] that took place at the Bauhaus in the 1920s. For Moholy, the Dessau school was at once a laboratory of visual experiments and a photographic subject where scenes of communal life clamoured for attention. This view from below gives prominence to architectural details such as the horizontal balcony rails inspired by the parapets of ship decks. Notably, the curvature of the cantilevered slabs is a reminder of the force of gravity in a modern building that appears to float almost weightlessly.

While the titular subject smiles at the camera, a couple of fellow Bauhäusler cheerfully pose in the background two floors up: a man balances between a handrail and the adjacent window ledge while a woman sits on the concrete balcony, her legs dangling off the edge. The terrace and balconies of the studio building, known as Prellerhaus, were the stages for numerous photographs of students and masters who struck playful and sometimes acrobatic poses. Their performative acts conveyed a sense of liberation by defying gravity.

Moholy explored multiple effects of disorientation in his work, climbing tall structures to take views so unfamiliar as to earn him the epithet of “aerialist.”1 However, he suffered from visual height intolerance. As his second wife, Sibyl, recounted: “Moholy usually became dizzy at unprotected heights. […] he took danger and discomfort as part of the total reality from which he never wanted to escape.”2 His bottom-up shot conceals that unease by exalting the feat of equilibrium performed by a daredevil colleague. Here the invisible tension between photographer and subject reflects the ambivalent nature of vertigo: a psycho-physiological phenomenon that is inextricably bound up with the experience of modern architecture.

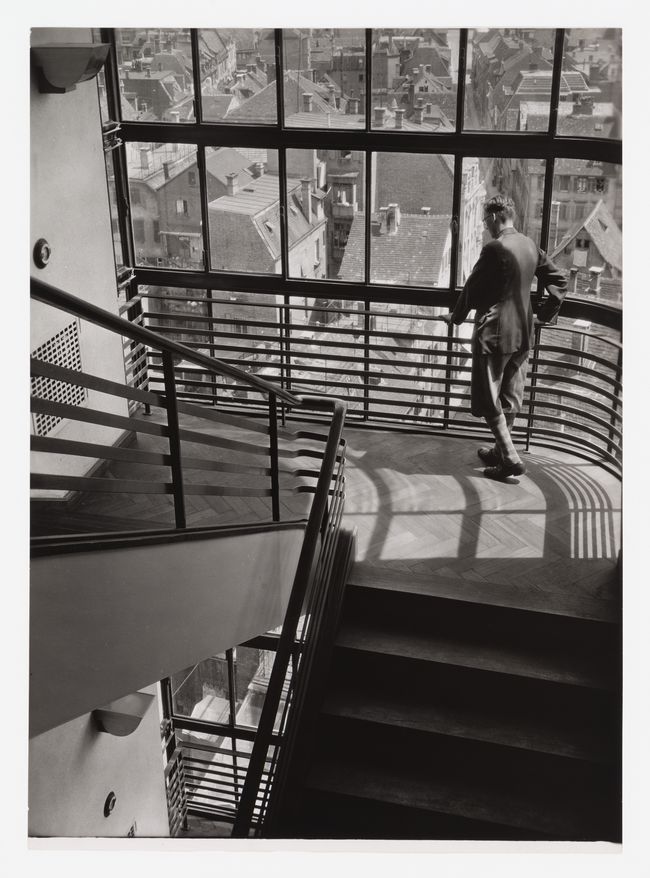

Horizontal railings also feature in a photograph taken by Adolf Lazi in the early 1930s inside the Breuninger department store in Stuttgart. Lazi’s image throws into relief the aerodynamic forms of the Streamline Moderne aesthetic, which was inspired by the Kaufhaus Shocken designed by Erich Mendelsohn in the same town. Yet, a palpable tension pervades the scene. A man stands on the glazed stairwell looking down upon the cityscape and holding the handrail with both hands. On a landing that doubles as a viewing platform, the horizontal rails help him find stability. As the sunlight flooding the interior glides along their curved lines, striated shadows accentuate the free flow of space: up and down the shaft and through the windowpanes. Caught in this flux, the subject seems to act as a conduit for the vertical forces that pull our gaze downward, conjuring an imaginary fall that is emphasized by the long depth of field.

Although the man is shielded from the sheer drop, the apparent disassociation between his arms and legs is somewhat enigmatic; his precarious posture is suspended between stillness and motion. Is he stepping forward, as might appear at first, or rather backward? Is he recoiling from the edge? As in a reverse shot of Moholy’s Prellerhaus image, this downward-looking view projects an uncanny sense of disquiet. While the former induces the thrill of vertical space, the latter captures the anxiety associated with it. Here, the stairwell becomes an architectural stage in which interior and exterior coalesce, only separated by a layer of glass. Stuck between these boundaries, the man seems to be frozen in space as well as in time. Although Lazi’s photograph was likely staged, one feels that its peculiar edginess may not have been wholly intentional. The man in knickerbockers will forever cling to that railing, and we feel the emotional strain of his state of suspension.

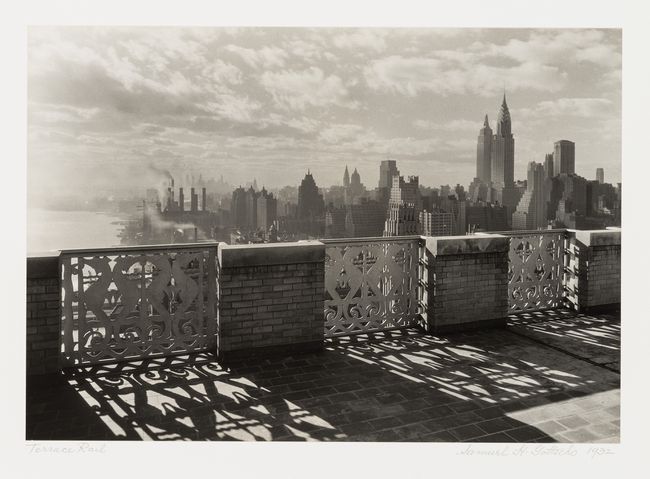

Since its opening in 1931, River House became one of the most exclusive apartment co-ops in Manhattan, its list of tenants reading like a “who’s who” of the booming metropolis. Built during the Great Depression, it attests to the resilience of real estate in times of economic crisis.1 In December 1931, photographer Samuel Gottscho took several photographs of and from River House. He spent a whole day shooting from atop the building, pointing his 5 x 7 camera in different directions under changing atmospheres.

A view from the 27th-floor terrace frames the skyline rising toward the top-right corner, where the Chrysler and the newly completed Empire State Building crown the cityscape. Unlike his other images, this one is simultaneously about and from River House. Shot against a sharp morning light, it is divided into almost equal parts by the edge of the parapet, an elaborate barrier made of ironwork panels alternating with masonry segments. Before he became a professional photographer, Gottscho was a salesman who traded in embroidery; this parapet might have reminded him of lacework patterns. Elongated shadows highlight its shifting textures, skewing their formal rhythm toward the right. As a result, the silhouette appears to stretch the depth of the terrace and keep us at a safe distance from the edge.

Rather than underlining the vertiginous point of view, the photographer was interested in framing the vista introduced by the apartment block, whose Art Deco architecture was the latest addition to the Manhattan skyline. The parapet here is not so much a barrier as a screen that intertwines River House with the surrounding cityscape, underscoring the privileged position of its residents.

-

The high-rise building had 78 luxury apartments including a triplex with 17 rooms and 9 baths, as well as a club boasting a swimming pool, tennis courts, a gymnasium, and a ballroom. Virginia Lee Warren, “River House: An Intimate Co-op with 18-Room Flats,” The New York Times, 15 May 1966, 90. ↩

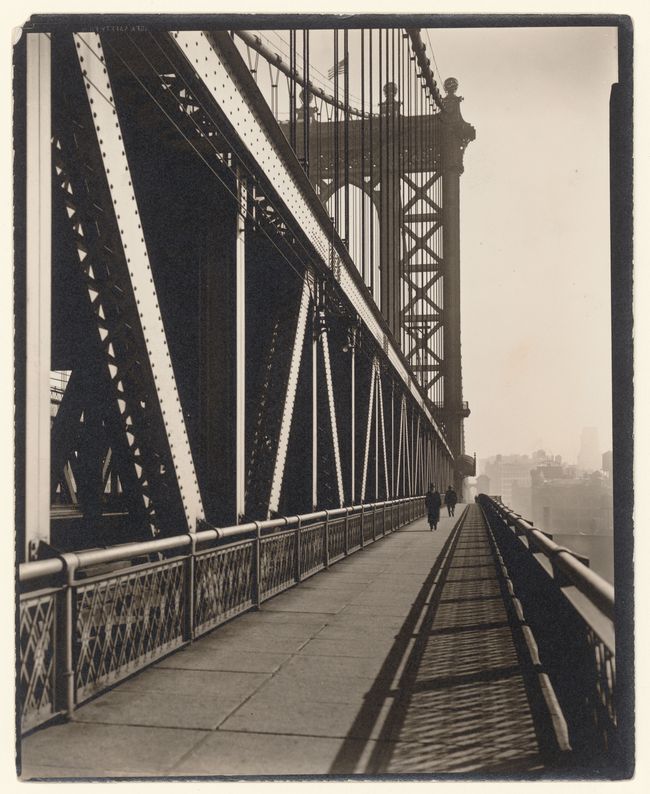

If Gottscho framed New York’s cityscape as a series of ageless monuments, Berenice Abbott conjured an altogether different look to the modern metropolis. Having spent most of the 1920s in Europe, she was impressed by the scale and pace of urban change on her return to America. Rather than picturing architecture as though it were frozen in time, Abbott regarded it as part of a social and spatial transformation she set out to document over the following decade. Her resulting photo book Changing New York (1935–1939), funded by the Federal Art Project, comprises a gamut of viewing angles epitomized by her now-classic “roof’s-eye views” of Manhattan’s canyons.1

Abbott’s photograph of the Manhattan Bridge expresses the experience of the abyss in a more subtle way. Here, she aims her camera straight, framing a one-point perspective whose vanishing lines run parallel to the walkway. Like Gottscho’s River House photograph, the iron parapet casts a slanted shadow on the pedestrian path located on the south side of the bridge and raised about 40 metres above mean high water.

Two human figures walk in opposite directions, keeping away from the outer edge. The tubular handrail on the parapet forms a shadow line that appears to define a danger zone—

a perception that was heightened at the time by the passage of trolleys and trains on the double deck, causing the suspension bridge to tilt and sway. Remarkably, Abbott had trouble with heights yet stood right by the edge of the bridge as she leaned toward the city’s canyons. Like Moholy, she deployed her own body as an agent of image-making. True to her “straight photography” approach, she depicted the Manhattan Bridge as a lived space, capturing the tension between thrill and anxiety that pervaded the metropolis at that time.

-

Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland, Changing New York (New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, 1939). ↩

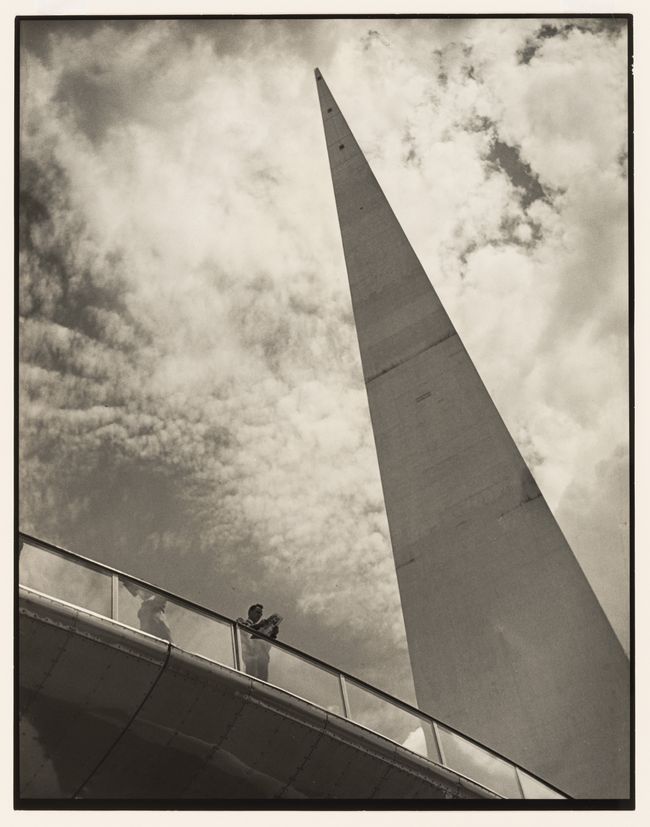

Elevated walkways were ever-present in the futuristic urban visions of the interwar period. They featured prominently in the New York World’s Fair of 1939–1940, which promised a glimpse of “The World of Tomorrow.” Designed to lift the public mood from the Great Depression, the event introduced several technical innovations from television to air-conditioning in a celebration of optimism that was cut short by the outbreak of World War II. Local photographers Samuel Gottscho and Frank Navara were among those who documented the spectacle on display at the Flushing Meadows-Corona Park; while the former focused on the formal aspects of architecture, the latter was more interested in how people interacted with the built environment.

Navara’s survey included the twin monuments of the expo’s Theme Centre: two white landmarks made of concrete and steel, known as Trylon and Perisphere, were connected by a long spiral ramp dubbed Helicline. The Trylon, a 210-metre-high pylon built on a triangular plan, fills the frame of one of Navara’s photographs—an upward shot in which the structure, often likened to a spire or obelisk, appears to pierce the clouds. In the foreground, a man stands by the glass parapet holding a paper in his hands. A dynamic tension unfolds on the vertical axis, as our gaze falls up towards the summit, yet is also pulled down by the figure on the walkway.

The transparent barrier, so pervasive in today’s architecture, was far less common at the time. It evoked the utopian city of the future presented in a diorama inside the Perisphere, where spectators could admire a huge scale model from a moving sidewalk. Emphasizing the thin edge, Navara’s photograph resonates with Moholy’s Bauhaus shot, where the balcony rails reduced the parapet to its minimal terms. Glass barriers marked an evolution of this concept by combining material resistance with a diaphanous quality. The Helicline parapet befitted an exhibition that introduced new consumer products to the public such as colour film, fluorescent light, and nylon stockings. Not unlike that revolutionary garment, glass parapets were designed to protect and reveal at the same time, attaining a bold level of transparency while ensuring strength and durability.

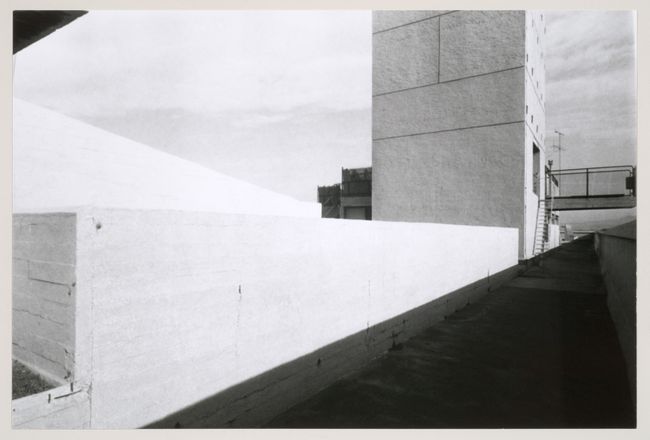

When the first Unité d’habitation was completed in Marseille, in 1952, it heralded a new way of living: the “radiant city” of the future shaped as a vertical community. The project marked the beginning of a fertile collaboration between Le Corbusier and Lucien Hervé, the Hungarian photographer who displayed a creative use of camera angles, coupled with an exceptional ability to render the effects of shadows across the rough concrete surfaces. Dotted with sculptural features, the roof terrace affords partial views of the surroundings over a high parapet wall. While the barrier provides a solid and safe boundary at the cost of restricting the panorama, multiple raised surfaces enable one to look out over the edge of the terrace.

One of them, inaccessible to the public, is the concrete platform that juts out of the elevator shaft. This peculiar “balcony,” fenced off on its open sides, is visible in a picture taken by Hervé from the pathway that runs along the terrace perimeter. Its ostensible function is to connect the shaft to the roof via an external access ladder; yet this alone does not explain its incongruous shape, which extends beyond the edge of the main façade. Pushed to the photograph’s edge, this cantilevered platform references the ocean liner aesthetic that influenced Le Corbusier. However, Herve’s composition is more ominous, for several people committed suicide from that point, so much so that locals came to regard it as an invitation to jump off. Whereas in other views Hervé framed the landscape beyond the parapet, here he evoked an invisible abyss that could be fatal.

Coincidentally, when the Unité was nearing completion, the philosopher Gaston Bachelard mused on the origins of the French word for guardrail [garde-fou]: “Guardrails protect us against that most basic, that most commonplace madness, the kind that can come over us as we cross a bridge, or pause at the top of a flight of stairs.”1 This mundane design element constitutes a perceptual and material threshold that safeguards us from the threat of the void while also shielding us from its call. Bridges, balconies, and sundry terraces are nonetheless trigger spots of the so-called “high-place phenomenon”; that ineffable impulse known as l’appel du vide. In the blink of an eye, Hervé’s photograph alerts us to the notion that architecture can be, without hyperbole, a matter of life and death.

-

Gaston Bachelard, Earth and Reveries of Will: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter (1948), trans. Kenneth Haltman (Dallas: Dallas Institute Publications, 2002), 267. ↩

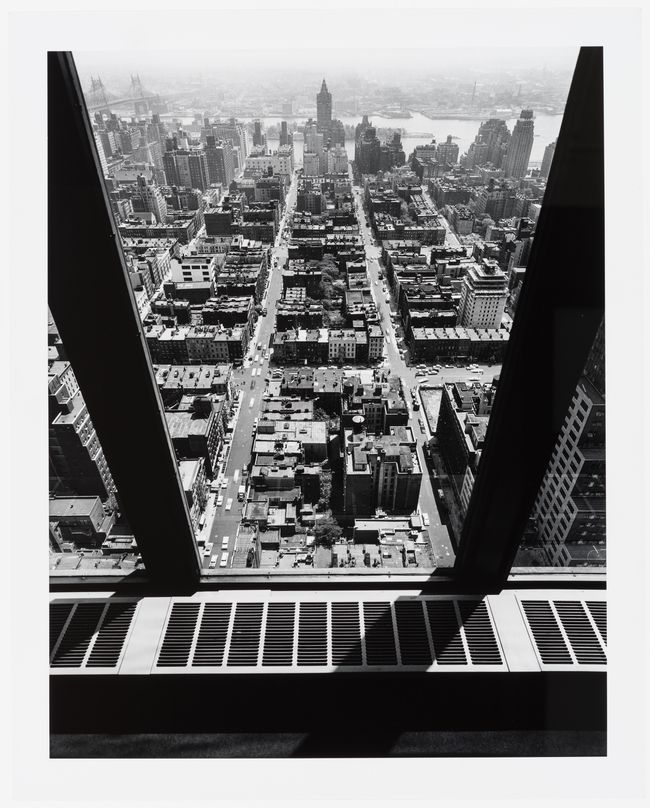

Over the twentieth century, the proliferation of office towers clad with curtain wall glazing normalized an encounter with the abyss. Yet, design professionals seldom recognize the complex psycho-physiological conditions that govern our perception of balance. Research into what is currently known as “visual height intolerance” was embryonic in the late 1950s, when Alfred Hitchcock shot Vertigo. The film was released the same year that the Seagram Building, the first office tower in New York with a floor-to-ceiling glass curtain wall, was unveiled. Although the glass plates cladding the façades were made using a traditional batch casting technique—the revolutionary float glass process was only introduced the following year—the Seagram’s interiors accomplished a degree of transparency that enabled majestic views over the cityscape.

Ezra Stoller captured these effects in giddy-making views taken from the top floor of the completed skyscraper. His photograph of Midtown Manhattan stretching to the East River frames the parallel streets of the gridiron between the building’s mullions, converging towards the River House tower at the top. However, a detail on the lower side of the photograph challenges the symmetry of the composition. The duct along the office floor reveals how the absence of visual barriers raised issues of perceptual stability. At the time of construction, real estate agents were concerned that vertical transparency might cause dizziness for tenants: “They worried that potential occupants would balk at being able to stand close to the window and be terrified or suffer vertigo in looking out and especially down without any element to retain them, and therefore would not rent space in the building.”1 To create a distance from the glass panes, Mies van der Rohe placed the air distribution system along the window walls, running at floor level with louvres at the horizontal plane. While depicting the cutting edge of the metropolis, Stoller’s picture is also a reminder that the visual thrills afforded by the all-seeing tower, along with the heady position of power it embodied, were inseparable from the spatial anxiety induced by the experience of the abyss.

-

Phyllis Lambert, email correspondence with the author, 13 February 2020. ↩