What is the architecture of interactive entertainment?

Farzin Lotfi-Jam discusses the legacy of Culture Lab with Brian Boigon

The video recording published in this article features the lecture by Farzin Lotfi-Jam marking the opening of Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994 and a conversation between Lotfi-Jam and Brian Boigon. It is accompanied by the transcription of the lecture.

There is a story often told about Le Corbusier visiting the Parthenon. After studying it for years from afar, he reportedly could not immediately approach it when he finally saw it in person. The object had already acquired an overwhelming presence in his imagination.

In a strange way, Brian Boigon became my Parthenon. For the past year, I have watched roughly twenty hours of archival recordings of Brian on stage at the Culture Lab. Repeatedly, carefully, frame by frame, gesture by gesture, speech by speech. You begin to notice patterns after that level of exposure. You recognize rhythms of delivery, moments of emphasis, moments of reflection, and moments of humour. You start to understand public intellectual presence as something constructed through time, attention, and performance.

When I finally met Brian in person, the encounter was a total delight. Sharp wit, immense curiosity, and a generosity open to all forms of conversation. That combination is rare. It is also central to Culture Lab.

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe. Graphic design by House9

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe. Graphic design by House9

Because Culture Lab was not simply a series of talks. It was a design atmosphere, a staged environment, and a format that structured how ideas were spoken, received, and circulated.

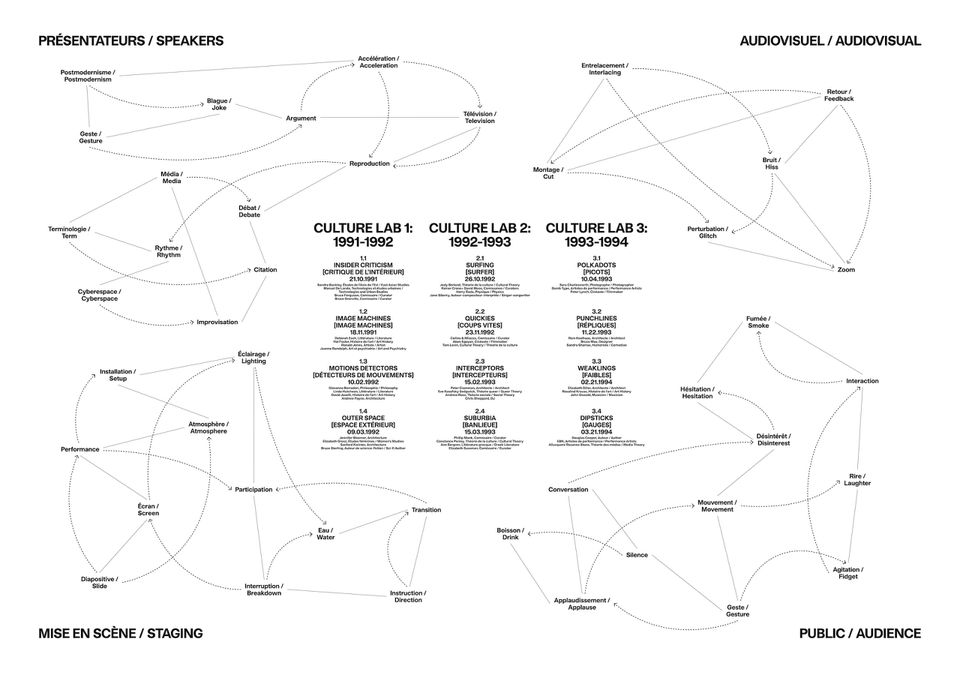

Culture Lab was a twelve-part symposium series staged between 1991 and 1994 in the back room of the Rivoli rock club on Queen Street West in Toronto. In the early 1990s, Queen Street West functioned as a dense media corridor: animation studios, artist-run galleries, broadcast media, software development, nightlife, and cultural production existed in close proximity. Labour, media, and collaboration overlapped spatially and socially.

Within this environment, Brian Boigon staged a radical format for intellectual exchange. He invited architects, philosophers, artists, science fiction writers, and theorists to speak under stage lights and disco balls, in front of a crowded audience, seated on stage with drinks in hand. Participants included figures such as Atom Egoyan, Elizabeth Grosz, Rosalind Krauss, and Liz Diller.

Boigon described the format as “fast talk for smart people,” a phrase that captures the structure of the event. Knowledge was produced through timing.

In a moment of incredible acceleration and expansion of new forms of media into every aspect of society, being in space together had a certain relevance. Through atmosphere, through attention, through engagement with a live audience, architectural discourse became a public event shaped by performance.

Boigon described Culture Lab as a form of interactive entertainment located at the convergence of television, the telephone, and the computer—something that was happening in that moment in the 1990s. Today we fully live within that convergence, as streams, podcasts, live feeds, multi-screen environments, and continuous real-time discourse shape how information circulates. Culture Lab anticipated these conditions in a live spatial format.

For Boigon, architecture extended beyond buildings. It included timing, staging, coordination, and participation. The symposium functioned as an architectural system that structured behavior across speakers, audience, media, and space. The format was tightly organized and every time, before the show would start, Brian would remind everyone of the format: fixed speaking durations, assigned themes, moderated audience microphones, programmed slides and video, calibrated lighting, dense crowd presence… These elements all shaped how ideas moved through the room.

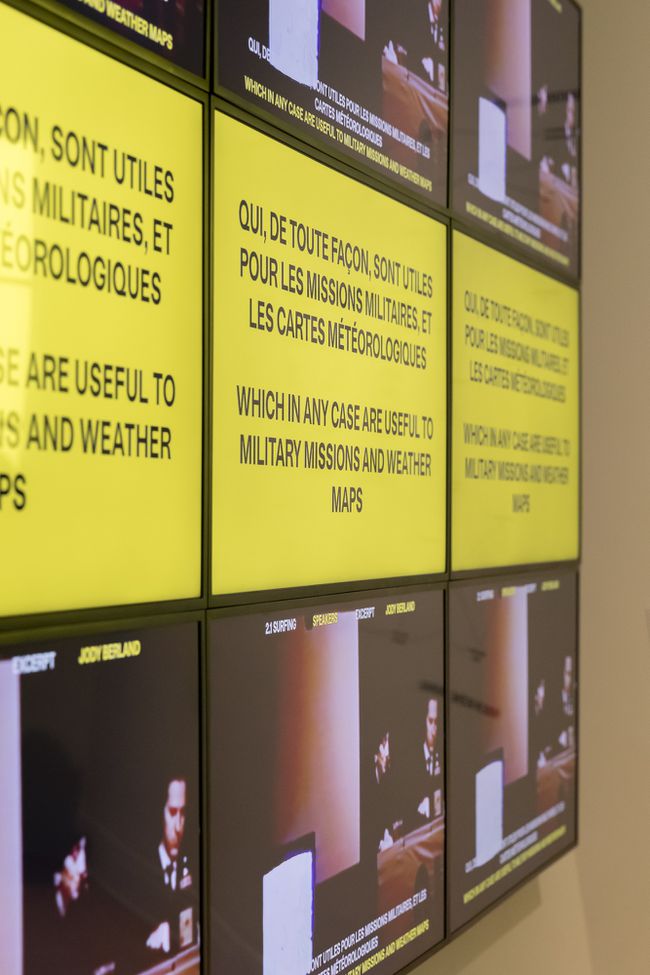

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe

The exhibition is structured in two main components drawn from the Collection. In the centre we have a series of tables laid out as a cross that we call The Expanded Archive. Here, different objects, documents, and forms of media from a plethora of projects that Boigon was working during the same time as Culture Lab. And surrounding this cross, on four walls, is what we call The Culture Lab Machine—a thirty-six-channel video playback system that revisits the recordings of the symposiums.

The Expanded Archive is organized into four conceptual sections that reflect a dimension of Boigon’s practice: Culture, Speed, Behaviour, and Interaction.

The Culture section situates Culture Lab within the media ecology of Toronto’s Queen Street West, where Boigon’s work unfolded across overlapping sites of labour and production: he worked at the Rivoli, was represented by S.L. Simpson Gallery, collaborated with Stephen Bingham of Alias Research, and engaged directly with early 3D animation software and computational tools. Broadcast media, including Citytv’s street-facing studio, offered parallel models of live production where content was created and shared in real-time. Culture Lab emerged from this dense network of media, collaboration, and urban proximity. The documents in the exhibition—invitation letters, equipment invoices, photographs, ticketing tools, slides, and recordings—trace how the event was assembled as a cultural system and a situated practice derived from urban proximity.

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe

The Speed section focuses on how Boigon redirected architectural theory in the 1980s and 1990s into operational material—a method for reading, sorting, and working across dense informational fields. At the University of Toronto, Boigon developed syllabi that organized readings into thematic clusters for rapid comparison and reuse. Collections such as Quick Theory assembled fragments from philosophy, media theory, and cultural criticism in ways that encouraged movement across disciplines. This pedagogical approach extended directly into Culture Lab. Topics functioned as probes rather than fixed conclusions. Speech unfolded within compressed time. Ideas circulated through accelerated exchange. Projects such as Speed Reading Tokyo—a publication project and an art exhibition that translated into visual and spatial form a reading of the dense media archaeology and urbanism of Tokyo—translated this method into visual and spatial form, presenting the city as a congested field of media, memory, and argument.

The Behaviour section marks the early integration of computation in Boigon’s practice. While many architects used computers primarily for drafting or form-generation, Boigon used animation software to study movement, posture, and response. Projects such as The Cartoon Regulators examined how characters act within predefined paths that pause, branch, and redirect over time. Research slides analyzed bodily motion frame by frame while drawings isolated posture, balance, and stance. These studies extended into wireframe models and digital scenes where motion followed repeatable trajectories. This work reframed architecture as a system for scripting action across time. Behaviour became a design concern grounded in sequence, duration, and interaction. When read alongside Culture Lab, the connection is clear: the symposium itself functioned as a behavioural environment, while speakers, audience members, moderators, and media operated within structured temporal parameters.

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe

The Interaction section presents Boigon’s transmedia projects developed through his B.B.Studios, including Spillville, Ketchup, and Splinters. These projects coordinated television, online platforms, animation, and physical artefacts within shared narrative environments. Characters guided users across screens and formats, while broadcast schedules, narrative pacing, and platform rules were synchronized across media systems. This required architectural thinking at the level of coordination and timing: stories, data, and participation remained aligned as users moved across different media and locations. Interaction here appears as a design problem grounded in liveness and continuity. At a moment when many people are thinking through complexity theory and bottom-up processes applied to the organization of architectural form, Boigon is directing that to the organization of audiences.

The central component of the exhibition is the Culture Lab Machine, in which the surviving video recordings of Culture Lab—approximately twenty hours of footage from ten symposia—have been processed and reorganized into a thirty-six-monitor installation with custom playback software. The system distributes up to two thousand clips across four monitor arrays: speakers, audience, staging, and audiovisual. This format allows viewers to observe how discourse was spoken, listened to, framed, and technically produced. Speech, space, image, and participation appear side by side.

Playback runs continuously. It shifts in speed and focus. Some moments unfold in parallel across multiple monitors. Other moments slow down and hold on gestures, pauses, or adjustments. The system loops, recombines, and redistributes material throughout the exhibition period. In doing so, the archive becomes an environment rather than a linear document. Culture Lab itself operated as a multi-channel experience in the Rivoli’s back room. Multiple conversations, visual stimuli, audience reactions, and media elements coexisted within a charged atmosphere of accelerated information exchange. The Culture Lab Machine extends that logic to the archive: viewing becomes spatial, attention becomes distributed, and time becomes layered.

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe

Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994, exhibition view, CCA, 2026. Sandra Larochelle Photographe

There is a productive tension in presenting Culture Lab within a museum setting. The original events took place in a rock club environment characterized by noise, density, and social energy. The museum offers a different spatial and perceptual condition. Rather than attempting to recreate the Rivoli, the exhibition focuses on the structural logic of the events: timing, synchronization, atmosphere, and multi-channel discourse.

Culture Lab emerged at a moment of significant technological transition. The early 1990s marked the shift from analogue media toward networked computation, digital animation, and emerging internet infrastructures. Boigon’s concept of interactive entertainment anticipated the contemporary condition in which media systems operate continuously across platforms and environments.

Today, we inhabit architectures shaped by datacenters, sensor arrays, distributed screens, embedded computation, and real-time communication networks. These systems organize attention, participation, and cultural circulation at scale. Looking back at Culture Lab allows us to revisit a moment when these transformations were becoming visible and actively theorized within cultural and architectural discourse.