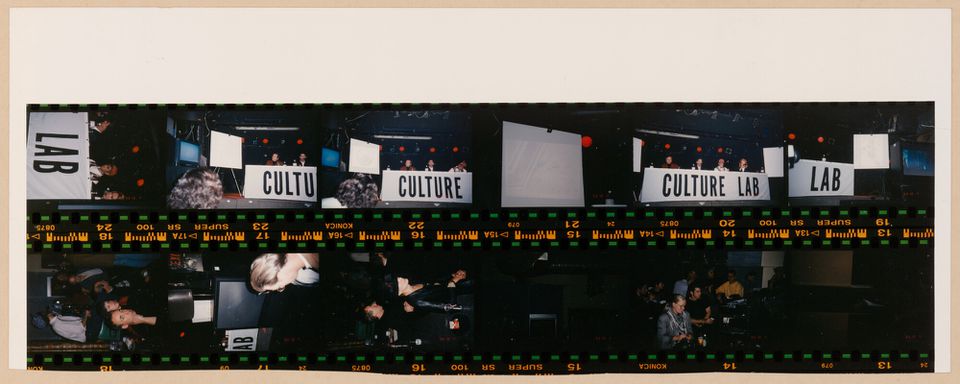

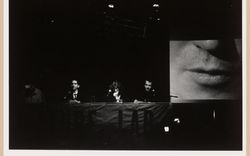

The nightclub redefined the notion of the symposium

Brian Boigon introduces the Culture Lab

This article features an edited transcription of a video interview with Brian Boigon. It is published in the context of the exhibition Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994.

- Brian Boigon

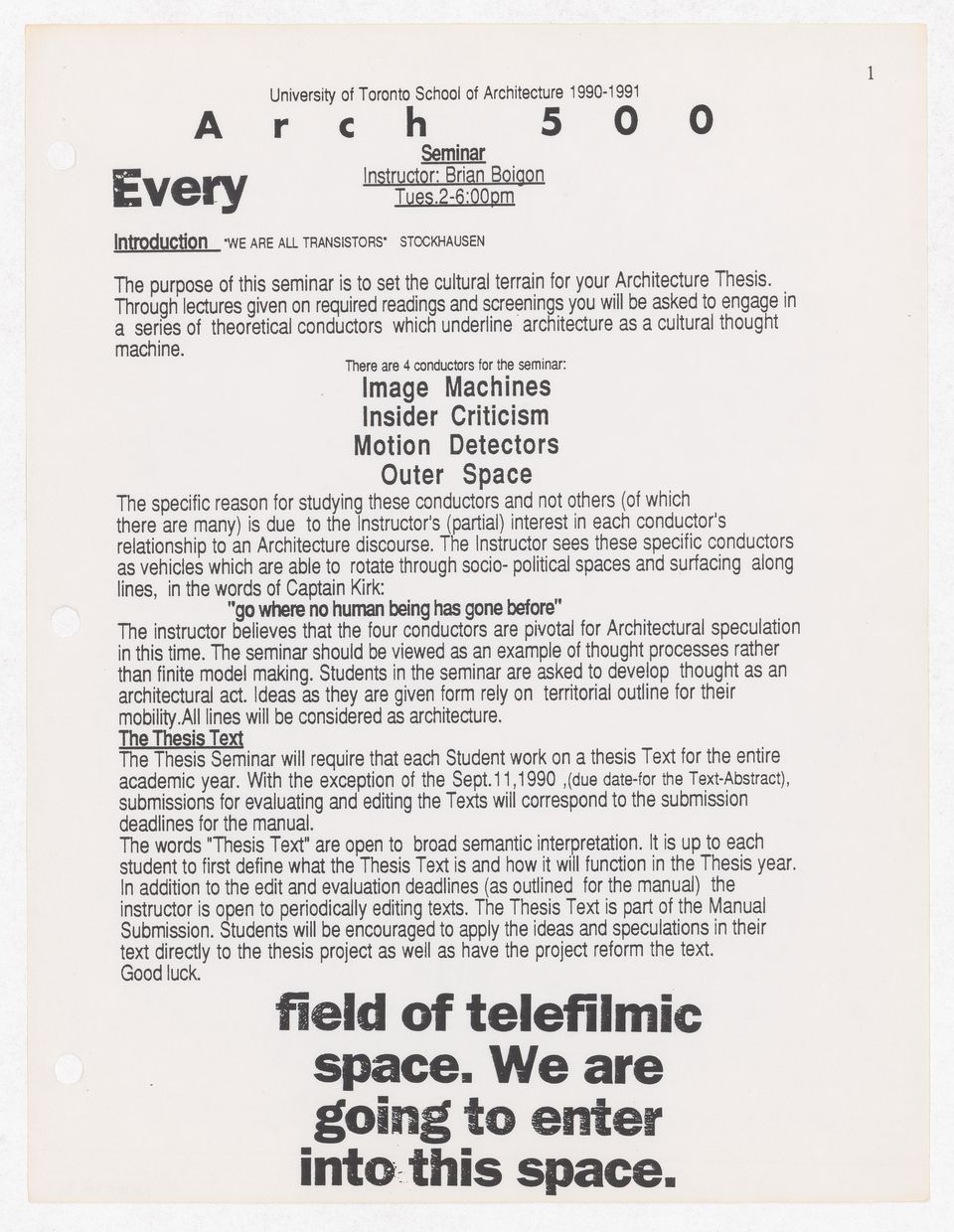

- I founded the symposium series Culture Lab in conjunction with my appointment at the University of Toronto School of Architecture from 1990 to 1994. It was a novel option to research the world of space, architecture, and form, and do it through the involvement of people in other disciplines—physicists, fashion designers, film directors, disc jockeys… There is a host of people that I wanted to include and combine and shuffle into the world of design, because you don’t want to have a boundary—or I didn’t want to have a boundary—between design and architecture and the rest of the culture, the rest of cultural production.

Brian Boigon on Culture Lab

- CCA

- What format did the Culture Lab take?

- BB

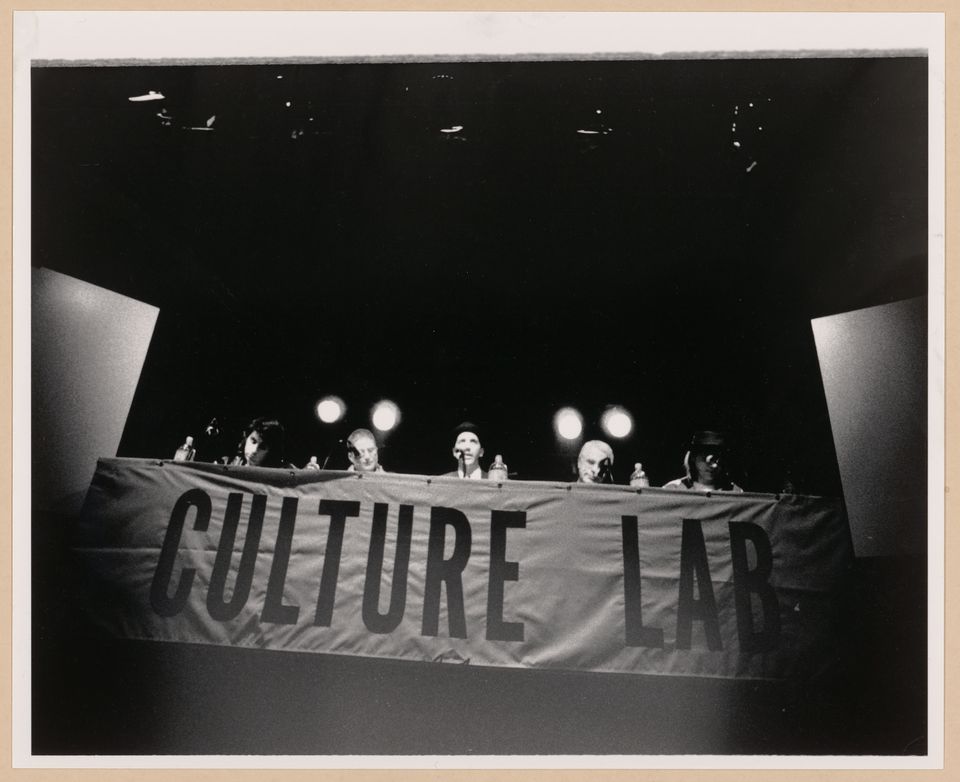

- That was a big question for me. First of all, where did it take place? It took place in a nightclub, a rock club, and I wanted that rock club to have a role. The participants were not used to speaking in those spaces, spaces that had some pedigree to them associated with scouting talent. I picked the Rivoli club on Queen Street, in one of the most dynamic strips of the city lined with galleries, independent bars, and performance spaces—from McCaul Street over to Bathurst, about a kilometre and a half long. I wanted the Culture Lab to take place there. Everything else was happening in the School of Architecture building and I wanted to move away from it, to move the consciousness of the individual away from feeling the comfort of the institution. I wanted to create another venue for that. So where it took place was very important.

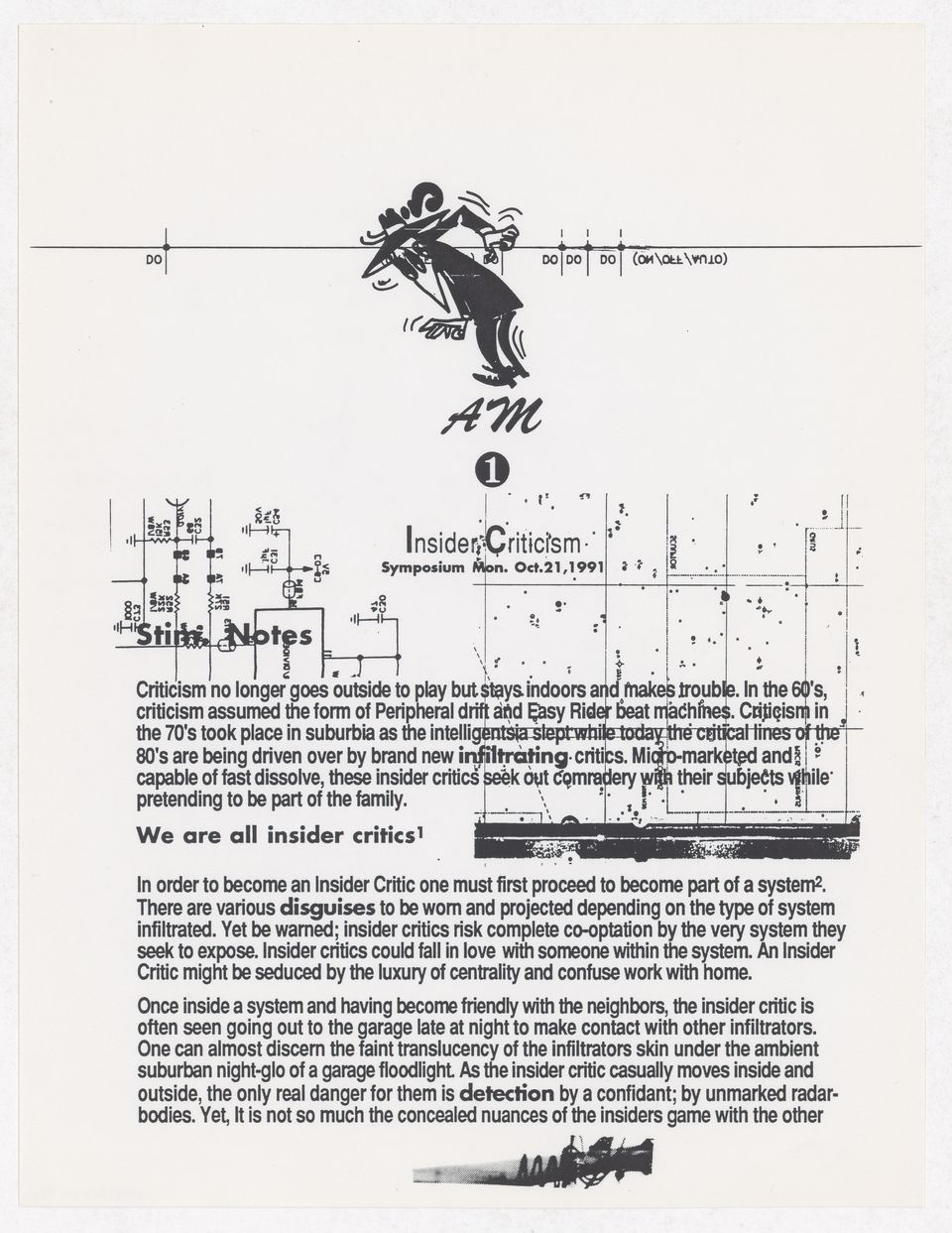

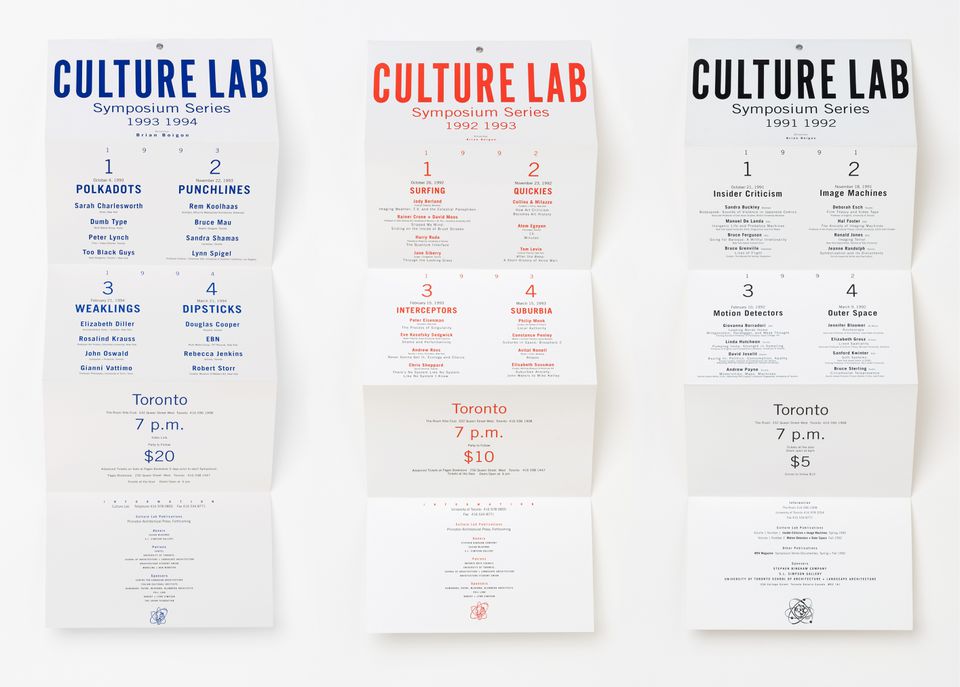

Then I figured out the format. I gave participants one sheet of paper with prompts related to the specific theme of their Culture Lab symposium, because each symposium or session of the Culture Lab had a different theme—for instance Dipsticks, referring to the instrument used for measuring liquids in a lab, or Insider Criticism—that I took from other disciplines.

- BB

- The format that pretty well followed was short-form broadcasting, like what Citytv was doing down the street from the Rivoli. Citytv was, along with MTV in New York, one of the first transparent studios, where you could walk along the street and look in while broadcasts were being recorded. They also had this thing where anybody could walk into a recording booth and talk about anything, and they would repackage all those videos into a show called Speakers Corner.

What we did at the Rivoli was also recorded by video and repackaged into two other routines. One was a closed-door round table between the participants and myself, warmed up together at the S.L. Simpson Gallery where I was exhibiting at the time. This closed, uninvaded round table did not involve the symposium question per se, but things like “What are you going to do? What’s your approach to the world that I’m presenting?” Mostly, they said “I have no idea.” But they did have an idea. In addition to this closed forum there was a forum in the green room, the classic sort of space at the back of the stage where talent get together and warm up. I didn’t change their green room at the Rivoli. I wanted to keep it exactly the way it was. It was super ghetto, grungy, you know?

People got very disoriented or nervous from that, but I mastered each of the spaces with a person: someone took care of the green room, someone took care of their drinks… So they were taken care of by all these people running around and getting them things.

- CCA

- How did your teaching contribute to the project?

- BB

- I was teaching in parallel to the Culture Lab and my teaching was, um, controversial—in the sense that I never posed the traditional building pedagogy of the architecture school. I taught things that were related to Culture Lab, like a course on the novel, related to things associated with fiction and particularly with The Canterbury Tales. I taught the Tales because it is very architectonic in its structure. I think that in my teaching I came up with cultural phenomena that resolved something or provoked something, like the Culture Lab did through the fact that it was in a nightclub and it redefined the notion of the symposium—for instance, having a nanophysicist and an architect like Peter Eisenman talk about the same thing.

- CCA

- How did you arrive to the themes and guest lists?

- BB

- I was working at the time at a lab, a science lab in a building called the MaRS (?) Lab in Toronto. A good friend who was a doctor was doing experiments there and I was asked to help him design his equipment. It was like a Lego project. You had to buy all this stuff like tubes and all kinds of instruments, and then I had to fit them all together. I never really experimented before in such a controlled environment. In medicine in particular, there are controls that are very precise and I thought that was interesting.

I was thinking a lot about how to set up the Culture Lab, what it would turn into, and how it would evolve. And that was an interesting challenge for me because I didn’t want to control these people, but I did want to. It was control without control. I had to insinuate things thematically, and I couldn’t tell people what to do. But they had to know that I expected certain things to come from them based on their work.

The way I came up with the players? They were all interested in the novelty of presenting their ideas in front of other producers that were not from their field. So, for example Atom Egoyan, the film director, was very interested in presenting because his work involved media in an intellectual sense. And he liked the combination of different subject matters that, in his mind, were associated. They all had these kind of flips through different disciplines. They just wanted to position themselves in a different world and talk about their ideas.

- CCA

- Which moments stood out to you the most?

- BB

- The club only held 150 people but I let in 250 and it was jammed. It evolved into the symposia becoming sold out, with a lineup down the street, three blocks down. It was cheap, five dollars a ticket. Anybody could afford it. So there were aspects of it that became out of control, like the crowds wanting to go see it. It just exploded as a popular anchor of culture at the time. It ran for three years like that. All those years were sold out.

- CCA

- What made the Culture Lab important at the time?

- BB

- I often question why it became so popular, but also why it became so significant as a beacon of cultural production for the city and for the architecture community, our communities. At the time—and I realized that in my teaching—architecture was at a standstill and the producers of experimental architecture were trying to find different routines and isms and combine them together in new ways. The Culture Lab became a site for that to happen. The timing was correct for it and it could happen only in Culture Lab because it was not really part of the university, it wasn’t institutionalized. But also technologically, it was a moment in the history of the transition between the analogue and the digital and a lot of the digital phenomena that emerged from that period also emerged from Culture Lab.

- BB

- One of the significant sponsors for Culture Lab was Alias, the software company that invented the spline model and 3D rendering that led up to Rhino. The computer rendering world of algorithms was always tied to the entertainment business. In a way Culture Lab was part of that innovation. It was an innovative period of clearly looking at other ways to make things happen in other in other disciplines, but also in other social sequences and materials.

The 1990s were significant important for the digital–analogue transfusion, transacting the results from one intensity and network to the other. And Culture Lab was part of that.

The exhibition Interactive Entertainment Architecture: Culture Lab, Toronto 1991–1994 is generously supported by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.