A collection of Chandigarh

Sangeeta Bagga on the Pierre Jeanneret fonds

I recently visited the CCA to study the archive of Pierre Jeanneret, who served as Chandigarh’s first chief architect from 1952 to 1965 and without whom Le Corbusier’s capital project could not have been realized. Having grown up within the built works that comprise the real “collection” of Chandigarh, I can personally relate to the city’s buildings and, with my architectural background, I can also consider them through a professional lens. I present a viewpoint of both user and critic. That sets my objective and tone for this narrative.

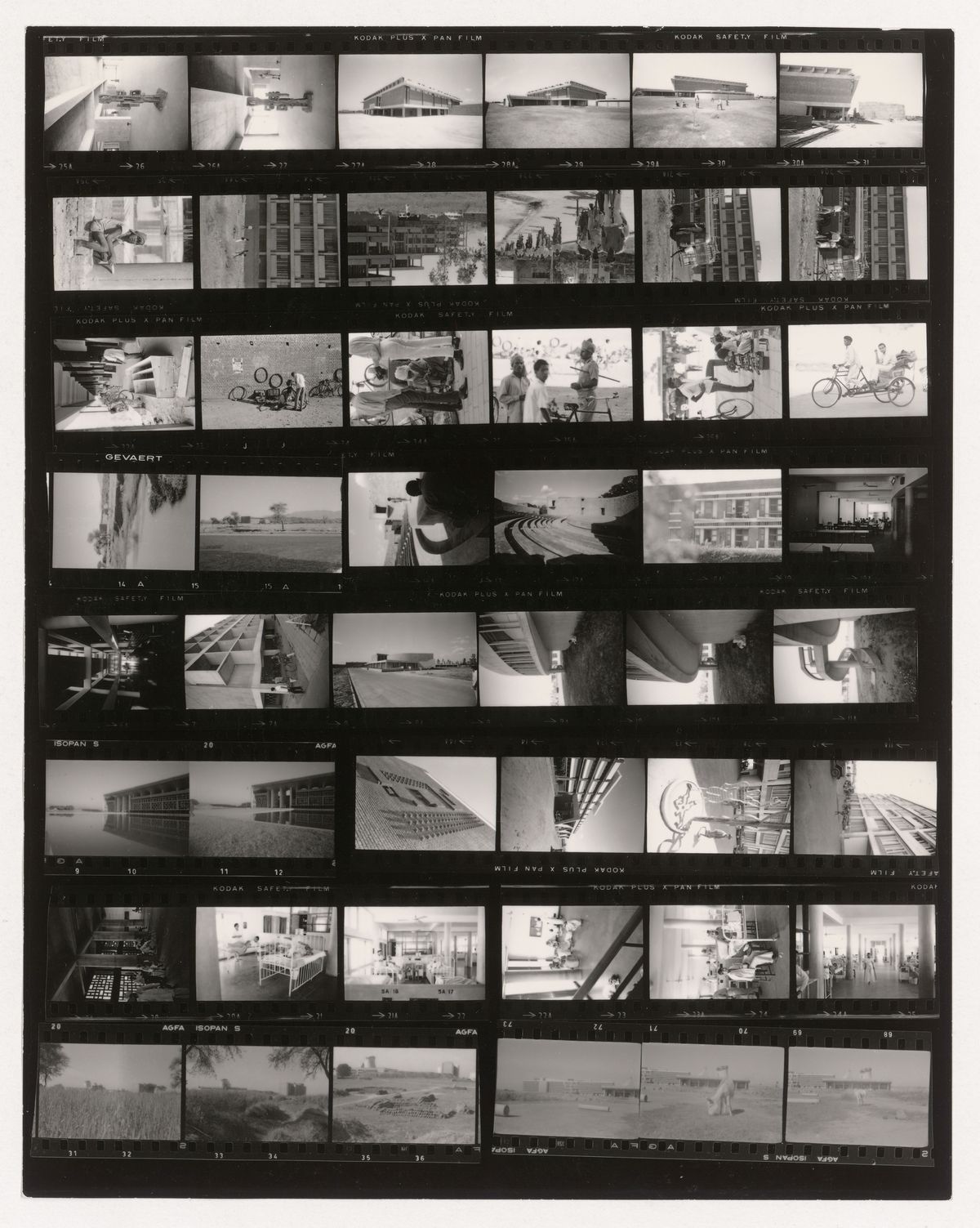

The archive is remarkable, voluminous, and special, as it is housed at a location away from both Chandigarh and Pierre Jeanneret’s home in Geneva. Originally held in Geneva, to which Jeanneret brought the materials during breaks from the Chandigarh project, this collection was then bequeathed to his niece Jacqueline, as Jeanneret remained a bachelor all his life and left all he had to her. It was then her decision to give the materials to the CCA in Montréal. Despite having been kept at various locations, the holdings at its final destination contain enough material and variety to offer a holistic kaleidoscope of works, while demonstrating the various techniques of documentation employed by Pierre to capture the city while it was under construction.

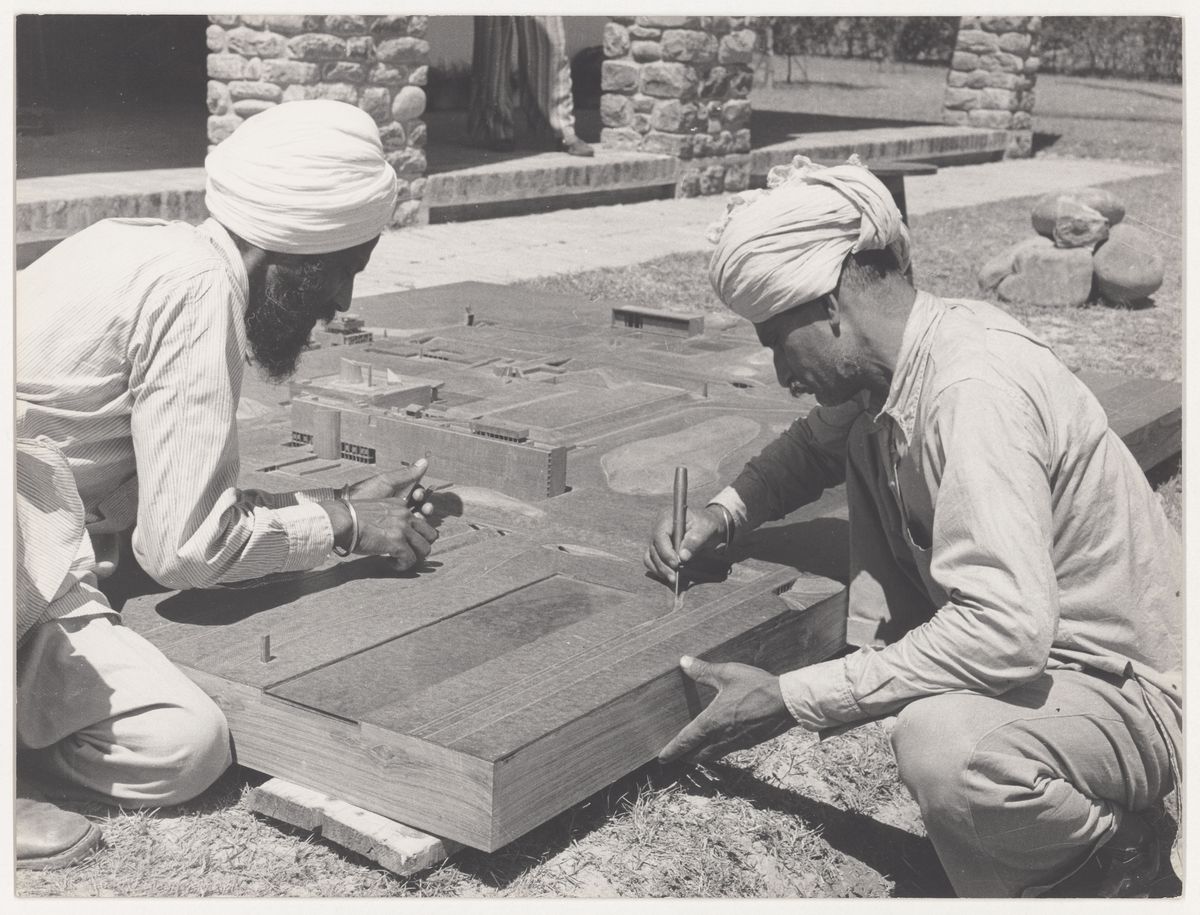

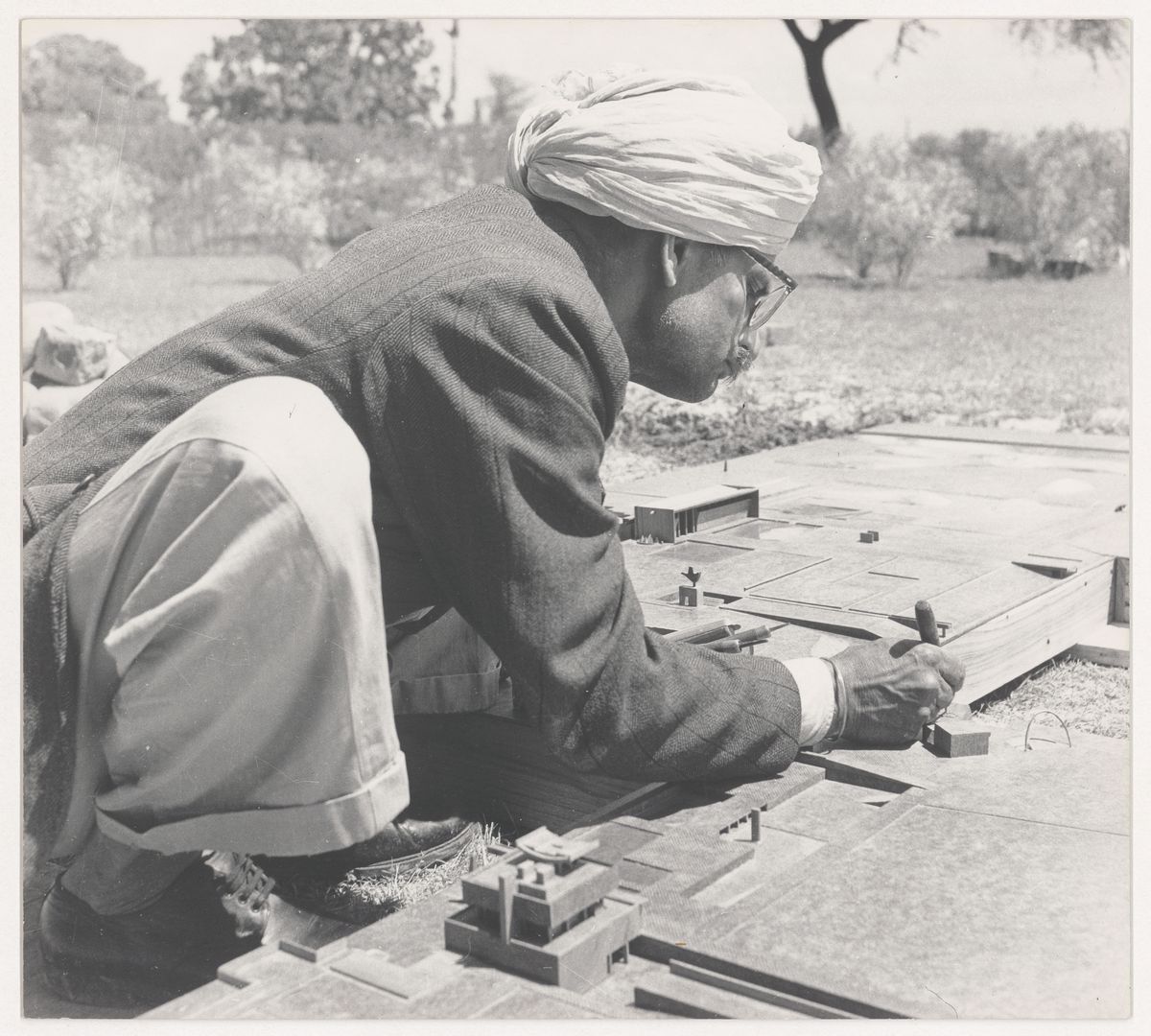

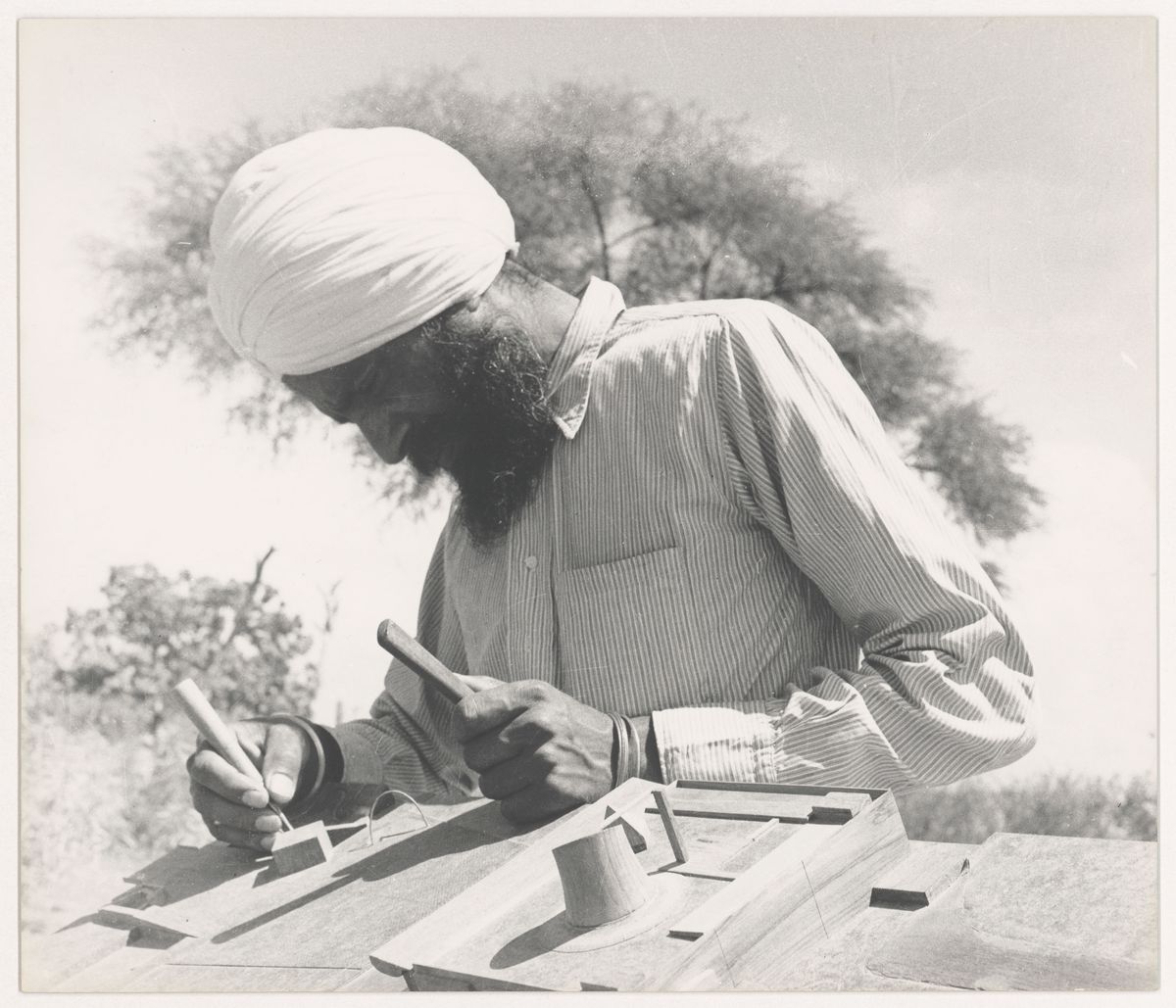

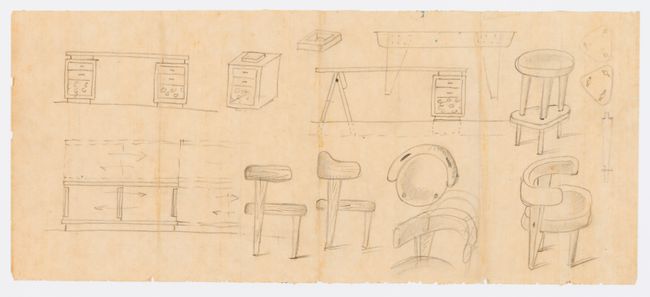

The archive comprises correspondence, personal letters, extensive photographic material, sketches, maps, and films that reveal Pierre Jeanneret as an architect, craftsman, and handyman. The archive also contains photographs from the personal collections of Jit Malhotra and other collaborators in Chandigarh, who were inspired by his character and craft. Scraps of paper, carrying freehand details and drawings—a windowsill sectional elevation, built-in storage, a windcatcher in a wall, a sketch of a cross-legged chair, a bamboo lamp, a gargoyle—can be found among the archived tracings carefully numbered and placed in cardboard boxes at the CCA. These objects appear somewhat casual at first glance, yet the extremely well-proportioned details, drawn by hand with India ink, coloured pencil crayons, or oil pastels, reveal Jeanneret’s eye for detail, consistency, and passion for his work. References to earlier drawings and sketches suggest a practice of detailed and didactic documentation that the team of Indian architects who assisted him also participated in, they themselves becoming inspired and groomed by Jeanneret through this passive learning method. These materials also suggest that this practice was perhaps a binding thread that led to the development of the architectural ethics and vocabulary popularly hailed as the “Chandigarh Style of Architecture.”

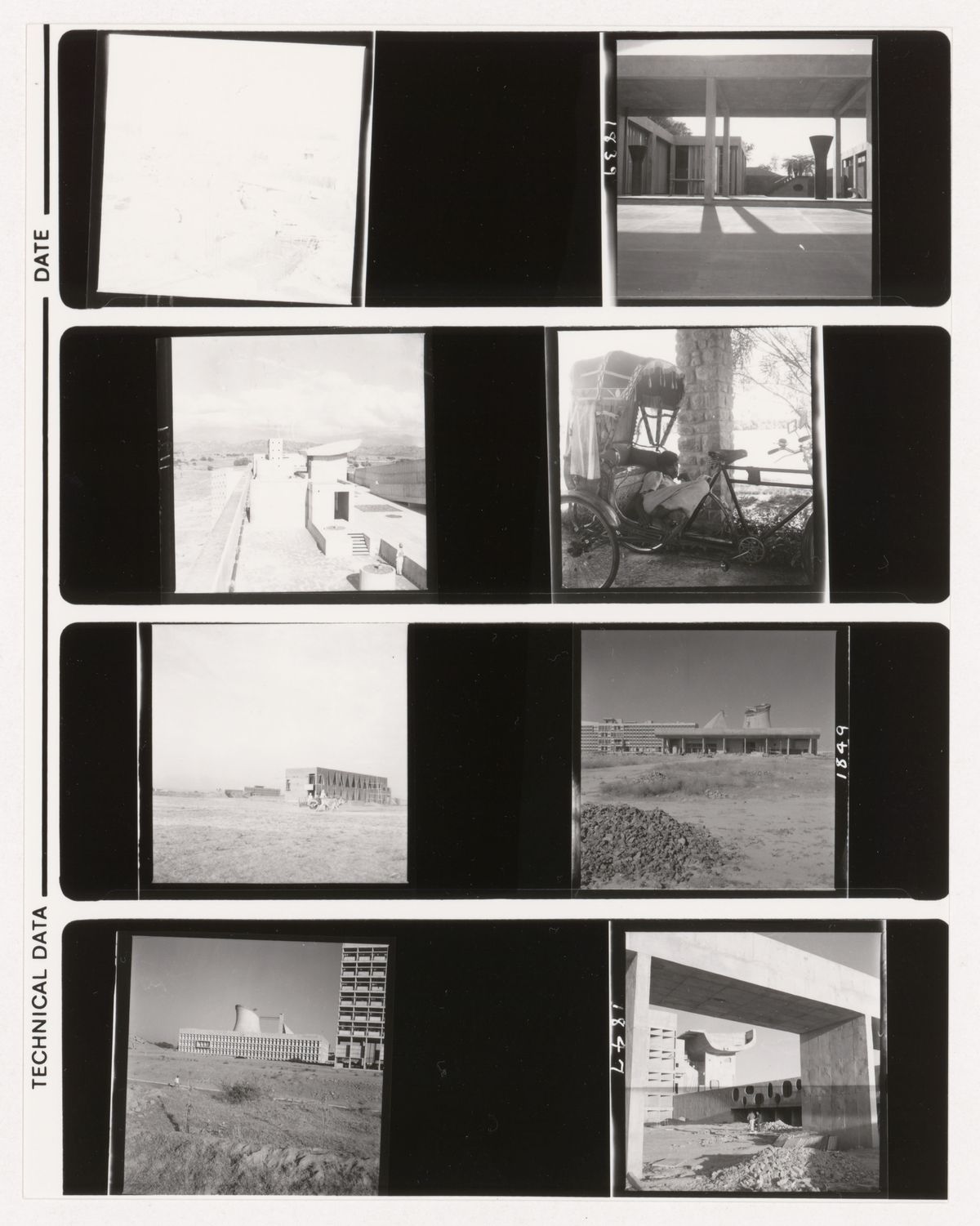

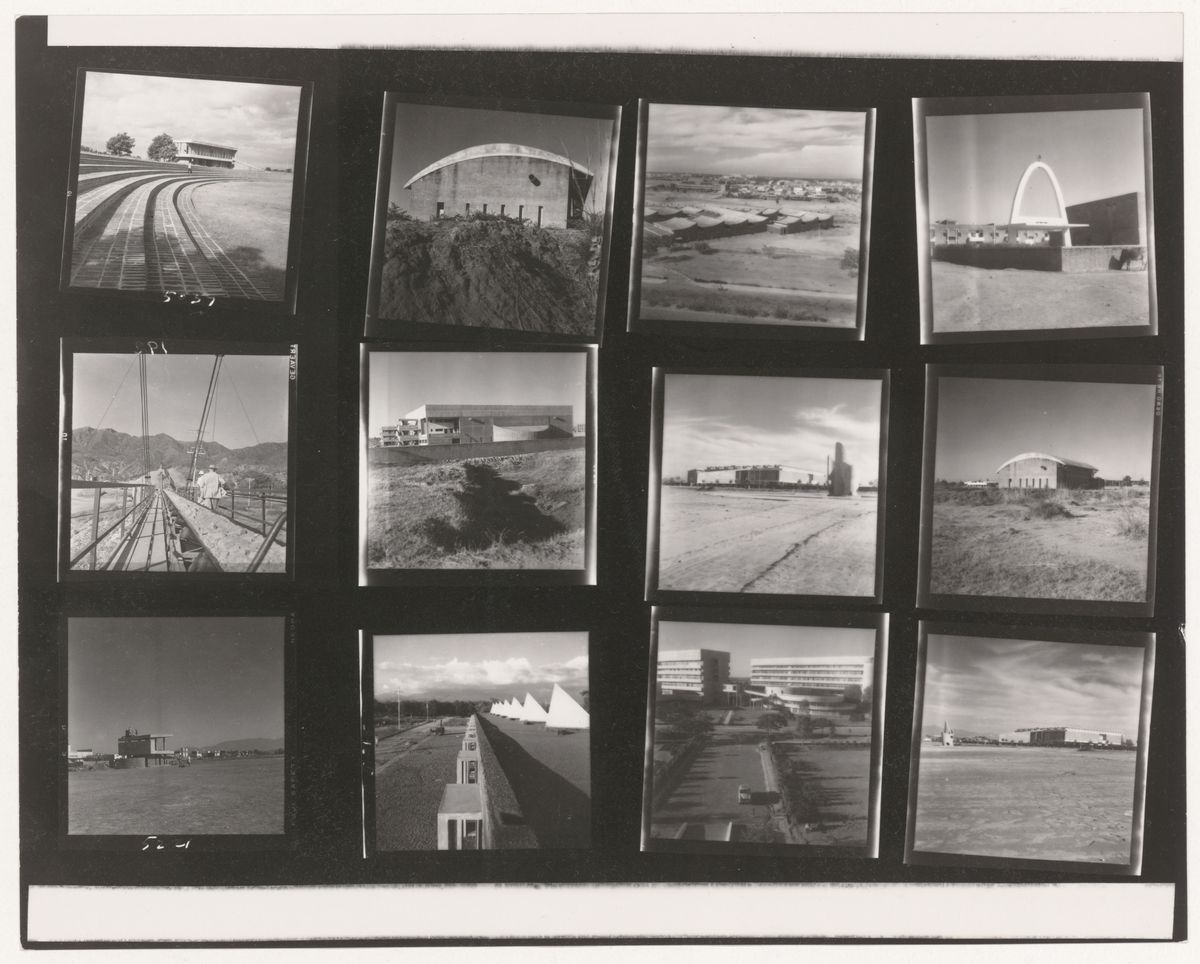

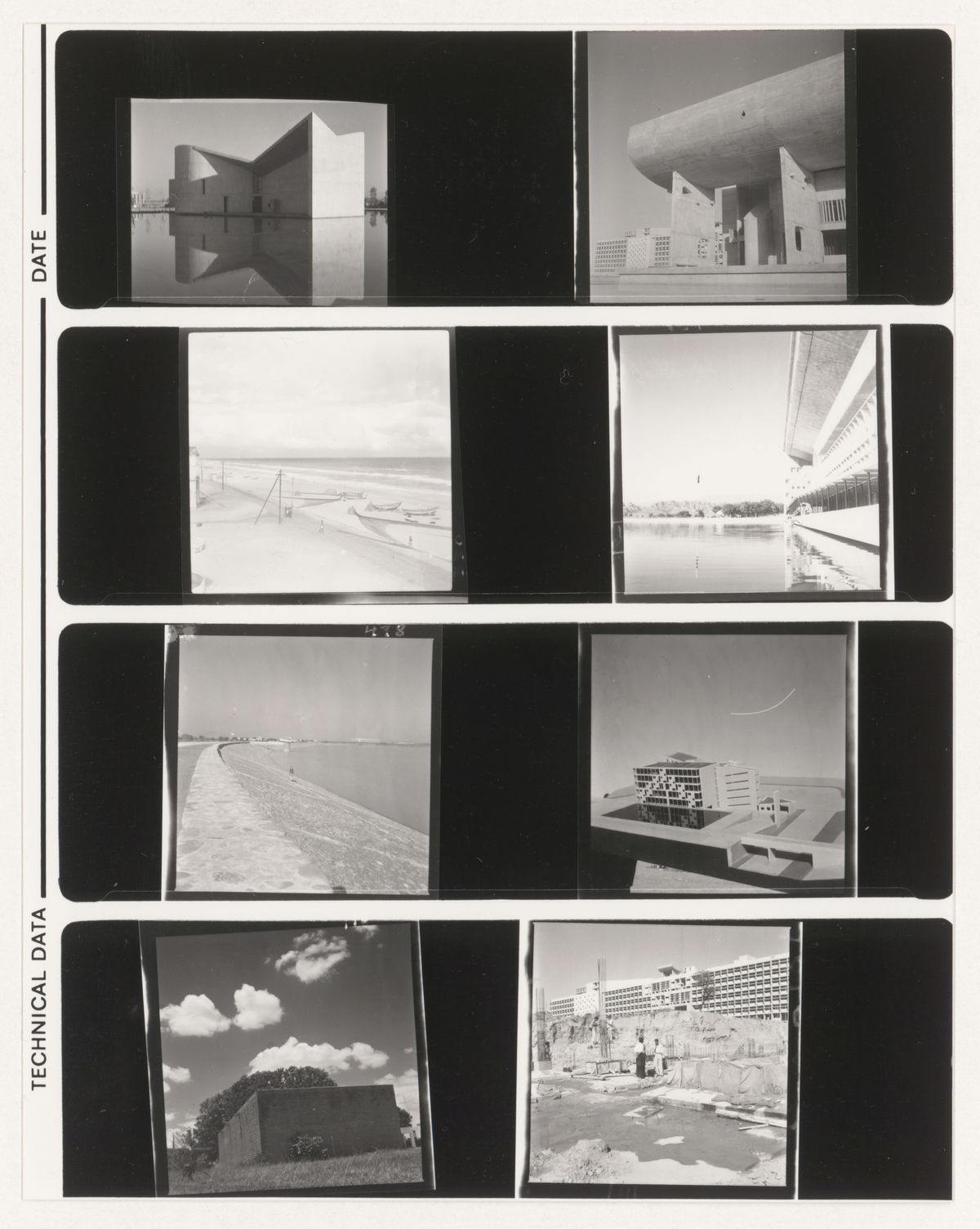

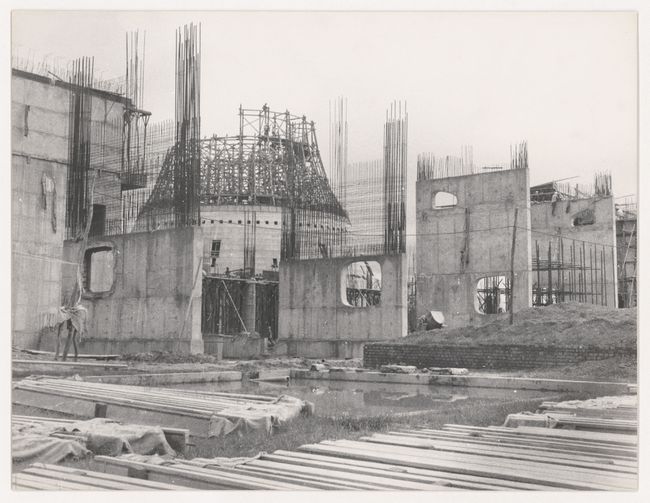

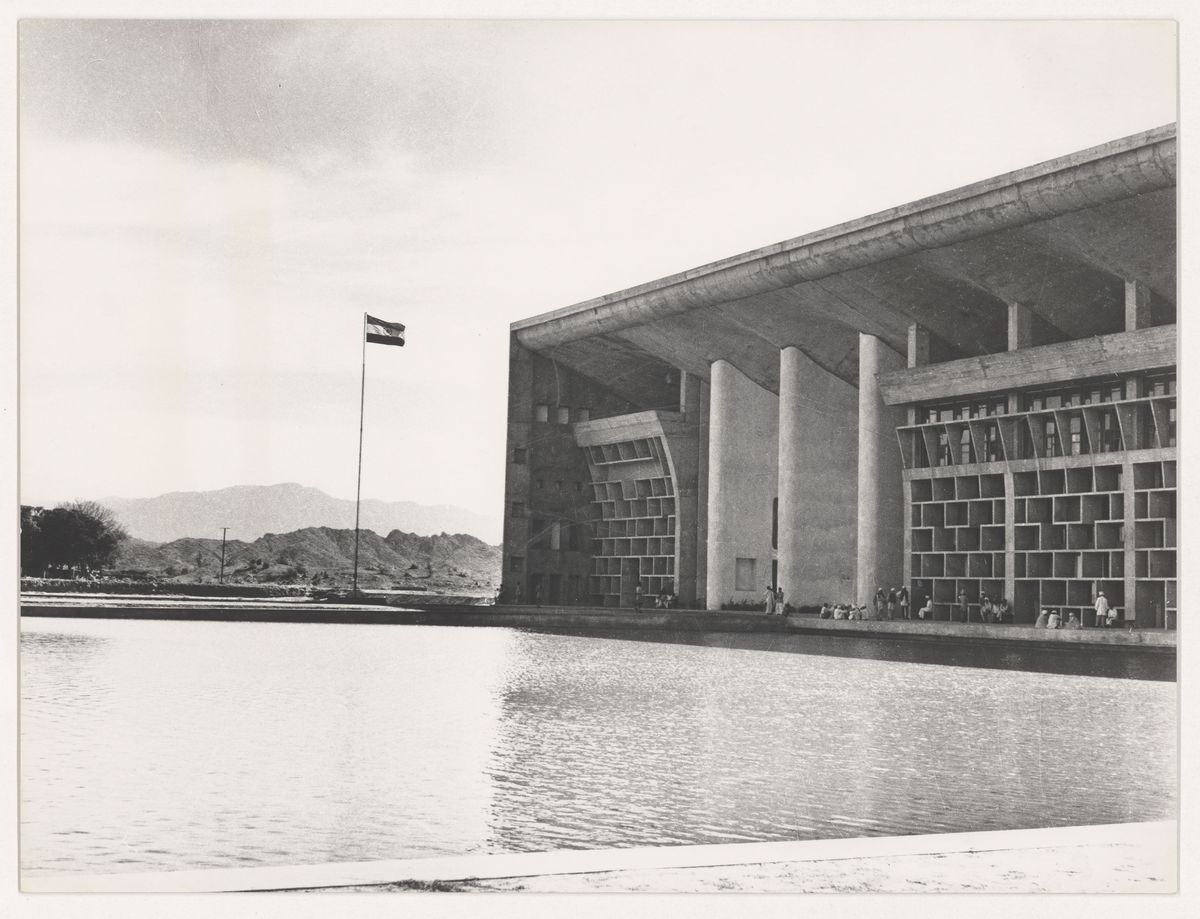

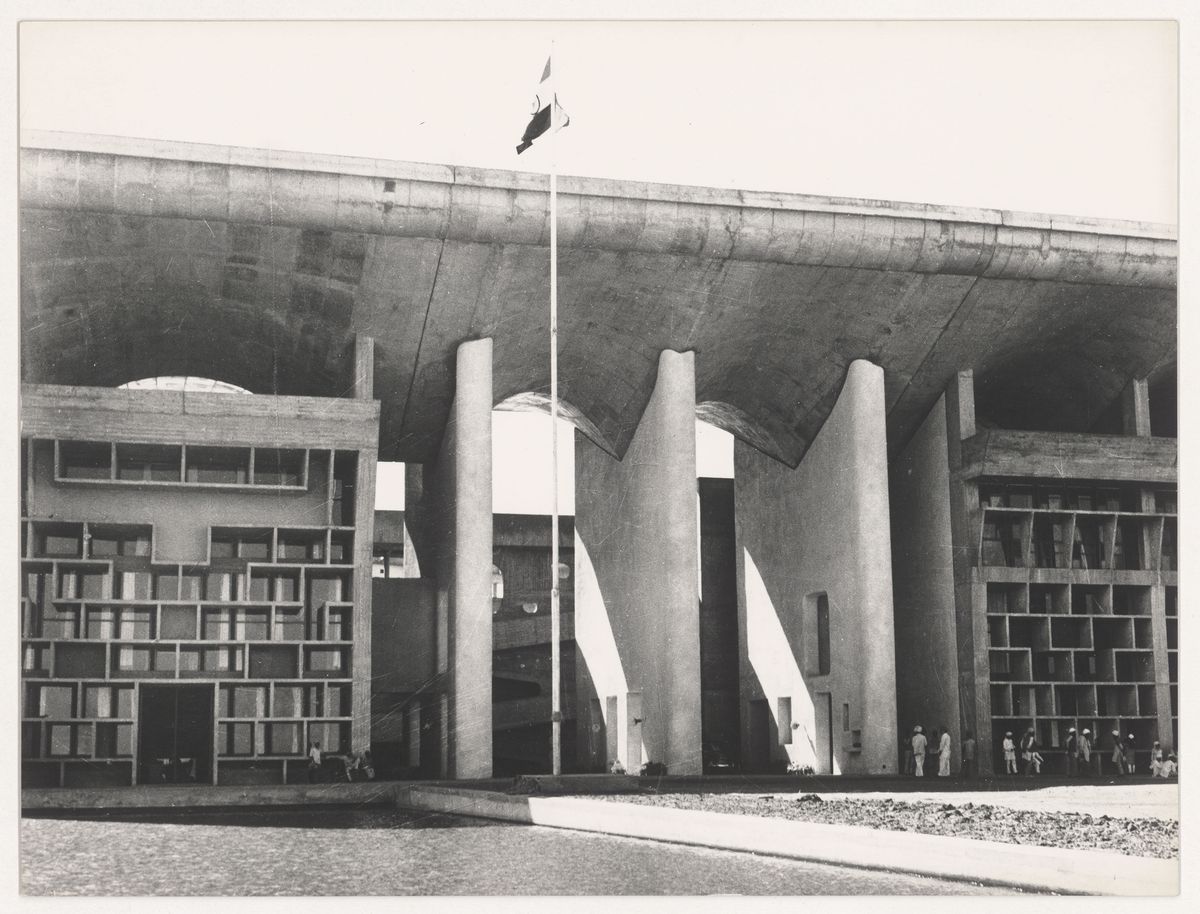

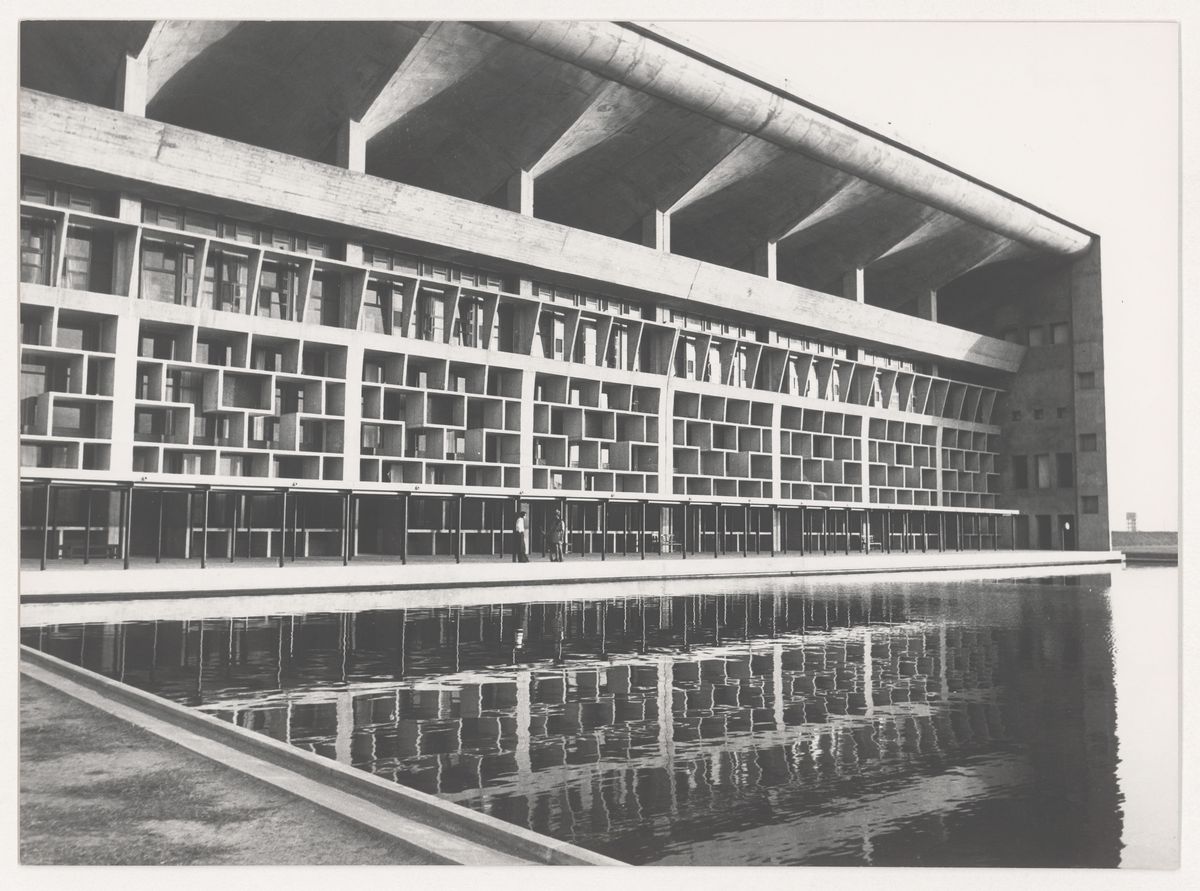

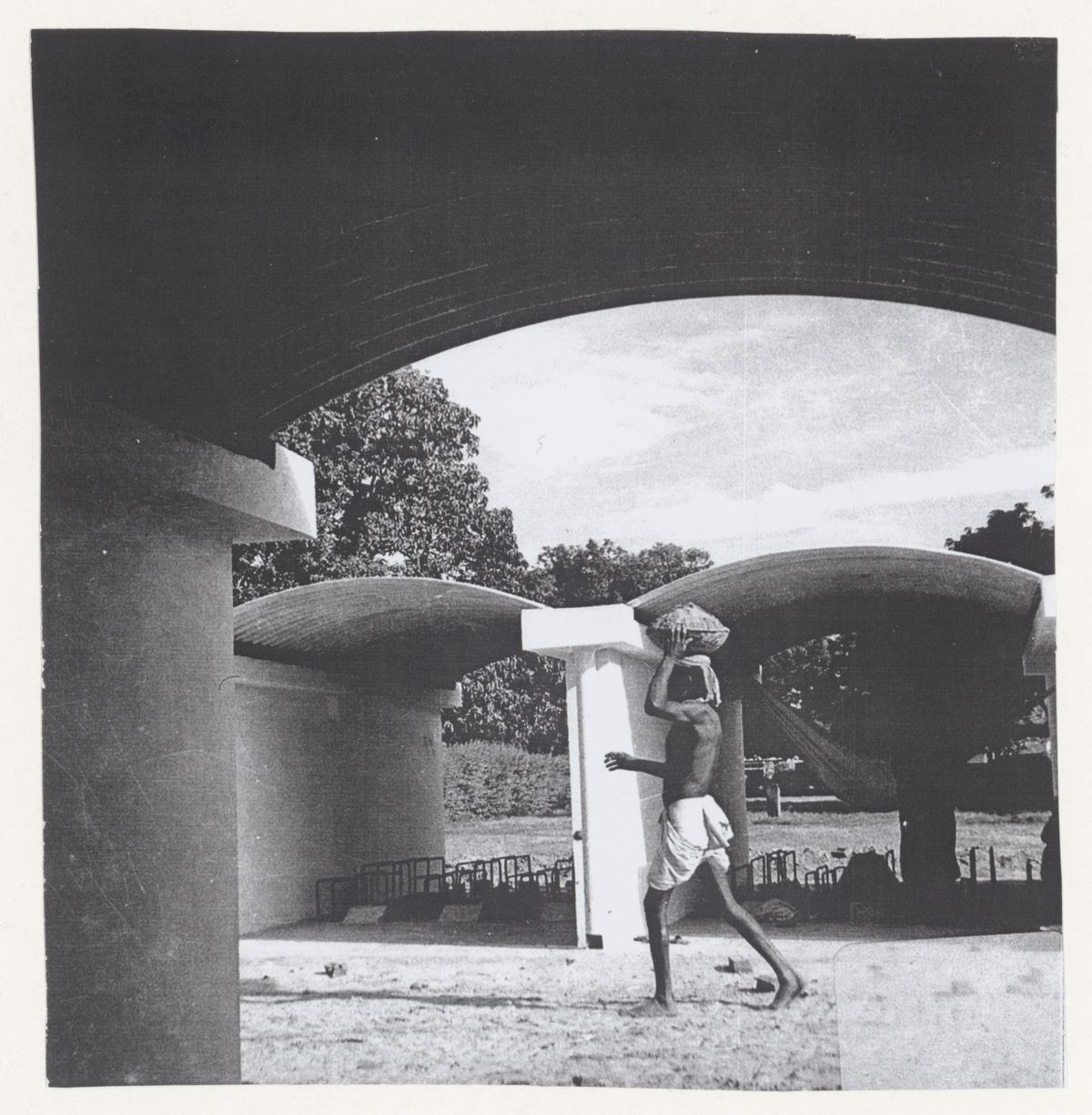

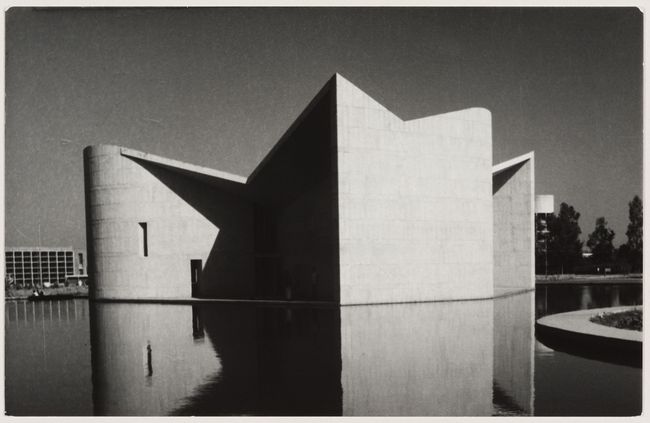

Jeanneret systematically appended notes onto his many drawings, as if at the back of his mind he felt that an annotated recording of Chandigarh’s making would be of referent interest to posterity. An outstanding example of this practice is seen in the materials for the Capitol Complex that are held at the CCA. It is by far the grandest project within the city, and set a stage for a great deal of acrimony between “the Designer” Le Corbusier and “the Implementer” Pierre Jeanneret, as it was the latter who received drawings from the atelier in Paris and converted them into implementable site drawings fit for execution at construction sites. The scale of the buildings is monumental, with an intricacy of levels and complicated details that yield a difficult-to-comprehend design. The innumerable photographs of the Capitol under construction explain how engrossed Pierre was with the execution of the buildings. Several images of the Capitol edifices—the Assembly extension and interior: one from the other, top, bottom, near, far—present a series of frames, like a changing of lenses in a camera lucida, which Jeanneret both possessed and liberally used. Multiple images of the High Court’s roof-top gargoyle, directing a waterfall that flowed to a ground-level basin, are captured from various angles, depicting Jeanneret’s work across construction, design, and landscape.

Unknown photographer, the Assembly under construction in Chandigarh, India, 1950-1965. ARCH268830, Pierre Jeanneret fonds, CCA Collection. Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret.

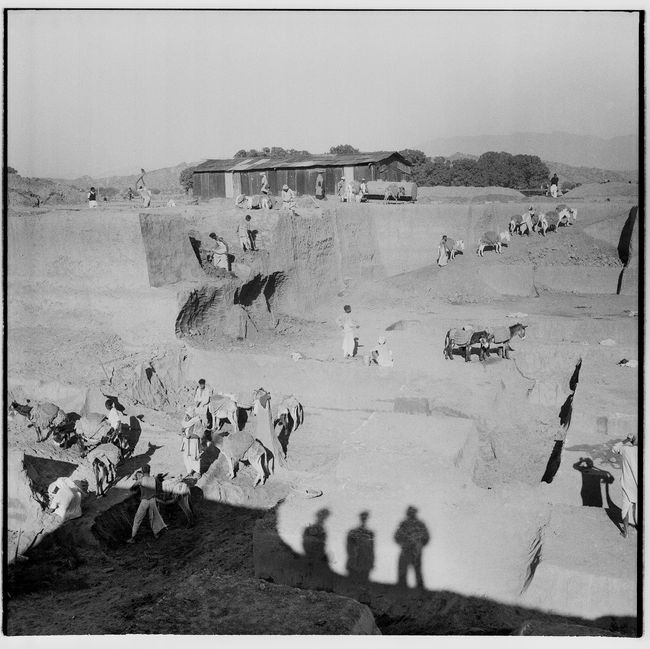

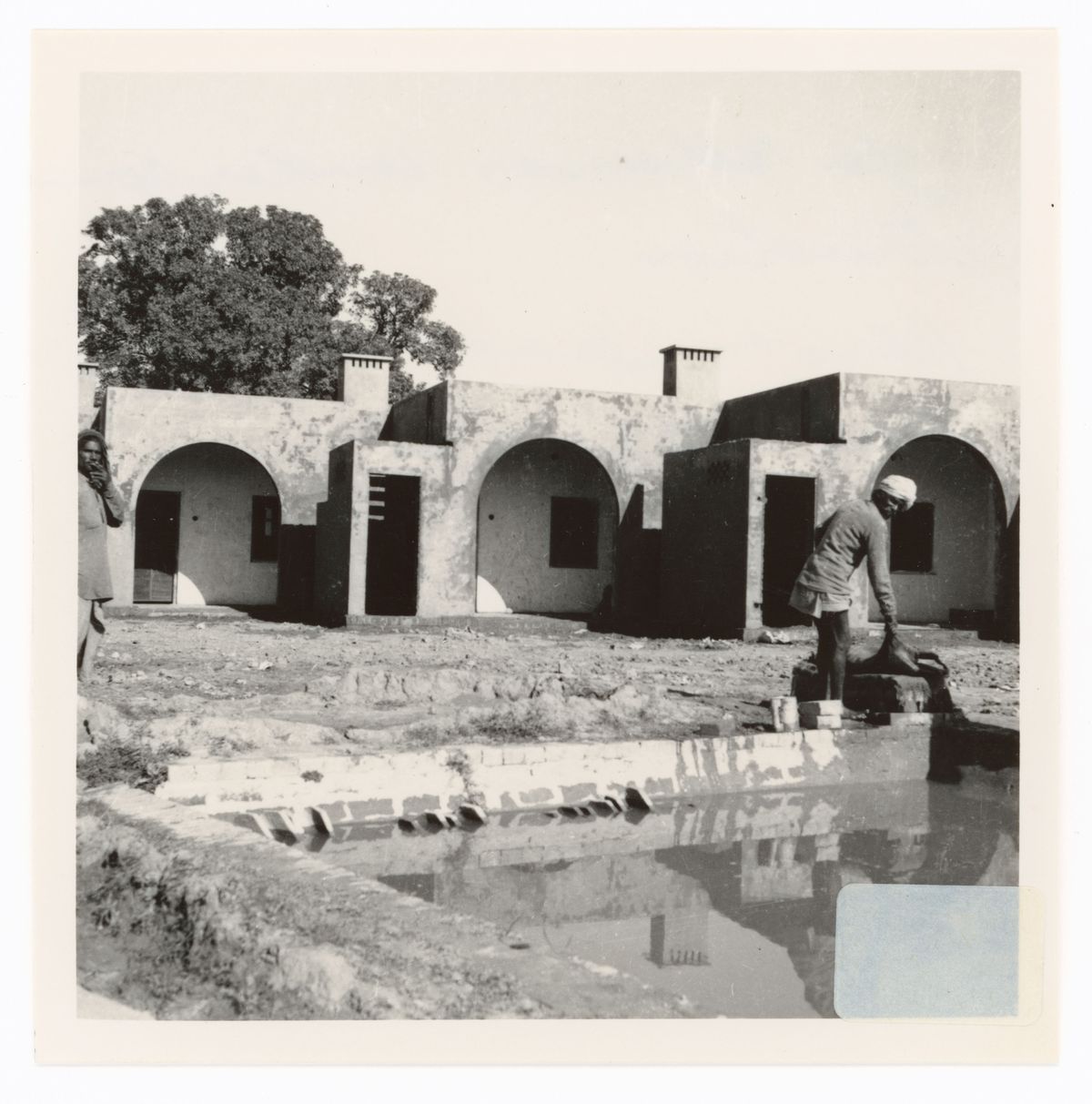

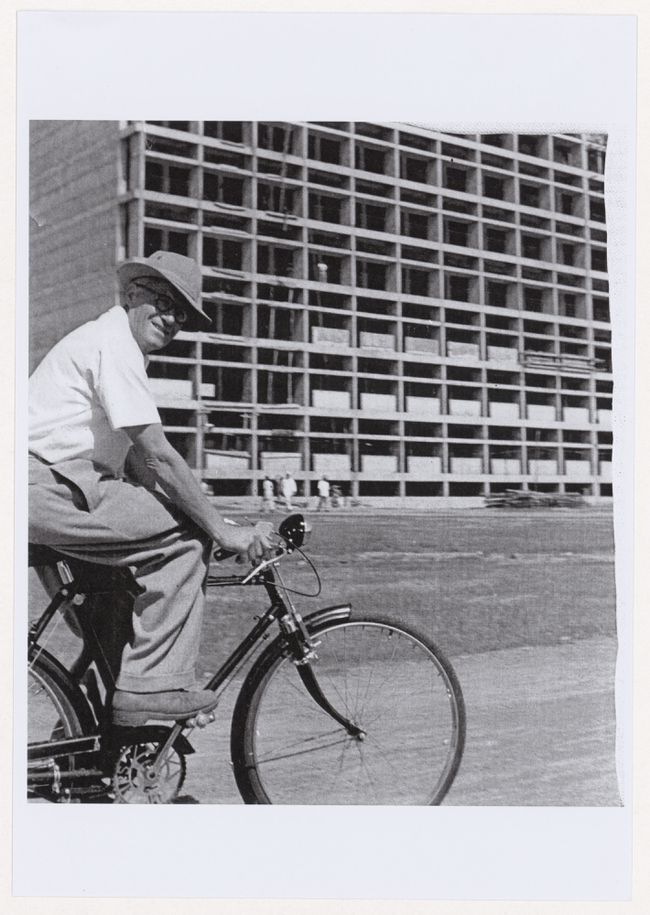

Though the Capitol Complex is credited to Le Corbusier, an in-depth study of the archived material brings one to admire Jeanneret’s painstaking realization of the Capitol on the ground, overcoming challenges of coordinating a diverse workforce most comfortable with Indigenous building techniques, utilizing non-mechanized means of construction, and, above all, overcoming language barriers as Jeanneret knew little English and only a handful of his collaborators—architects, engineers, and contractors—could follow French. Thus, the tool that Jeanneret relied upon most extensively for documentation and for reference was the camera.

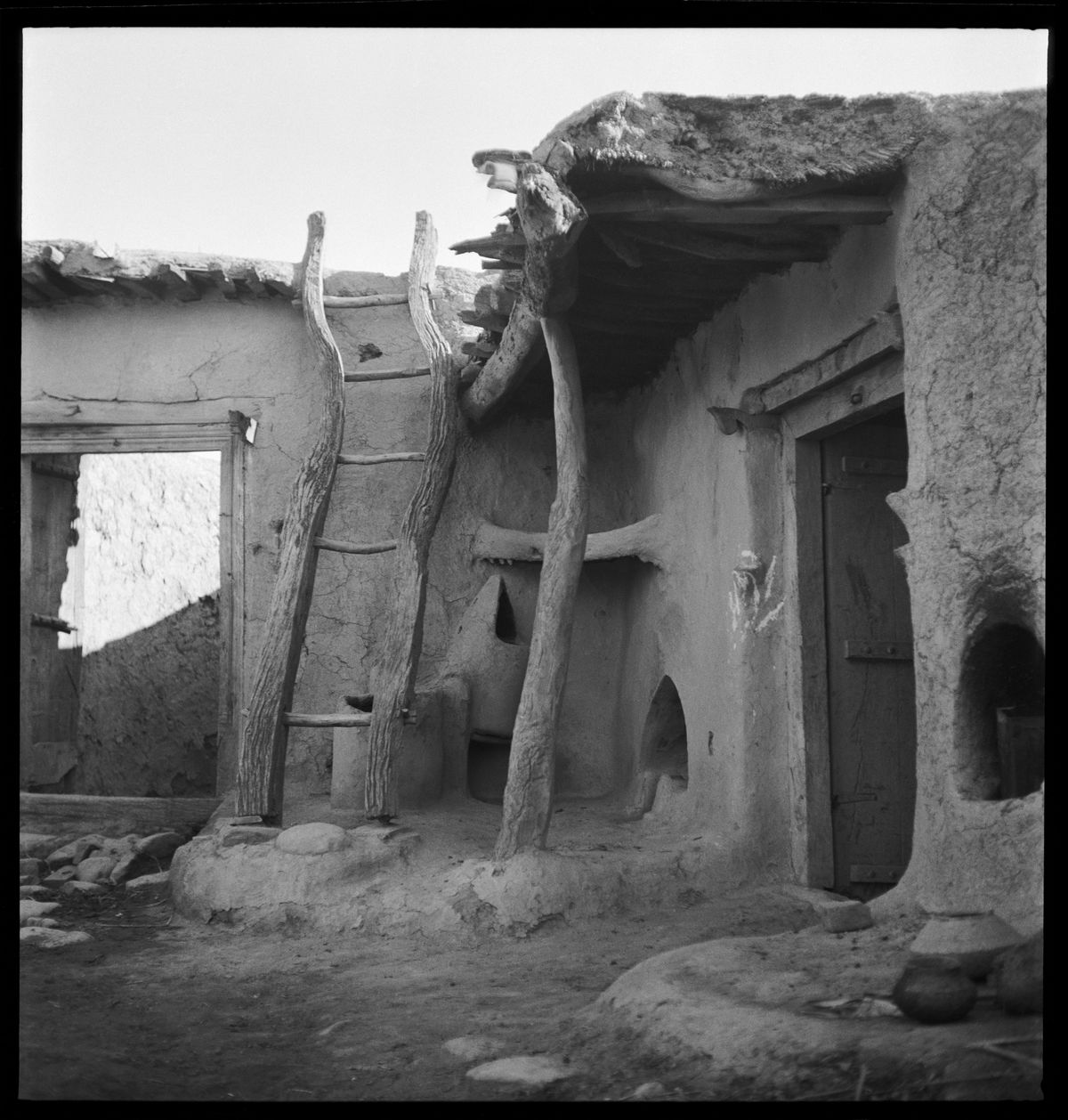

The lens also served the purpose of recording references during Jeanneret’s travels. A photograph taken in Jaipur with the Jantar Mantar in the foreground set against the Aravalli Mountains suggests that there may have been an influence of the same while siting Chandigarh at the foothills of the Shiwaliks. Another photo of the Mughal Gardens at Pinjore, with mountains rising beyond, presents perhaps another instance of picturesque inspiration. At one time, Jeanneret possessed seven cameras and he would often run out of film during his travels.

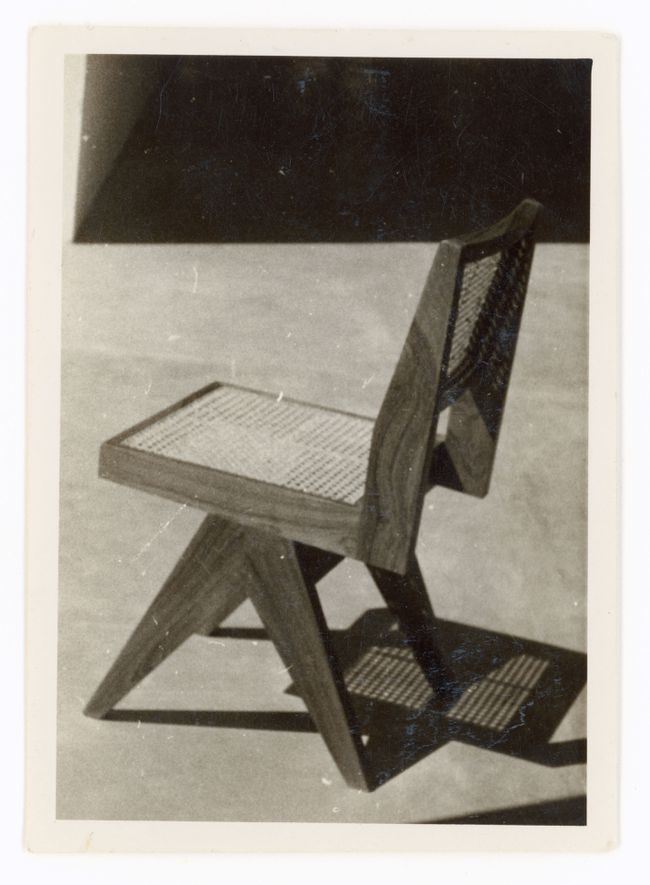

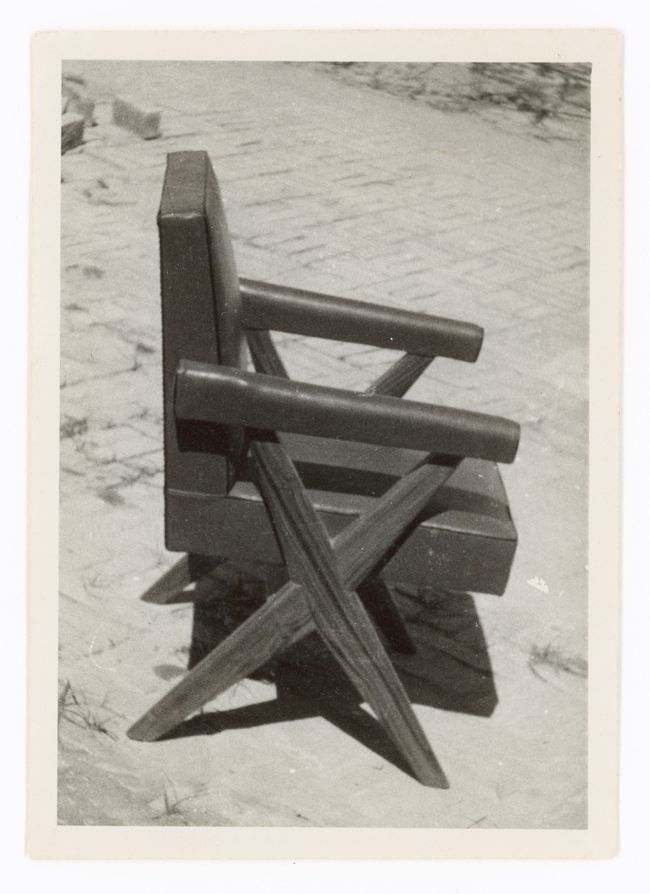

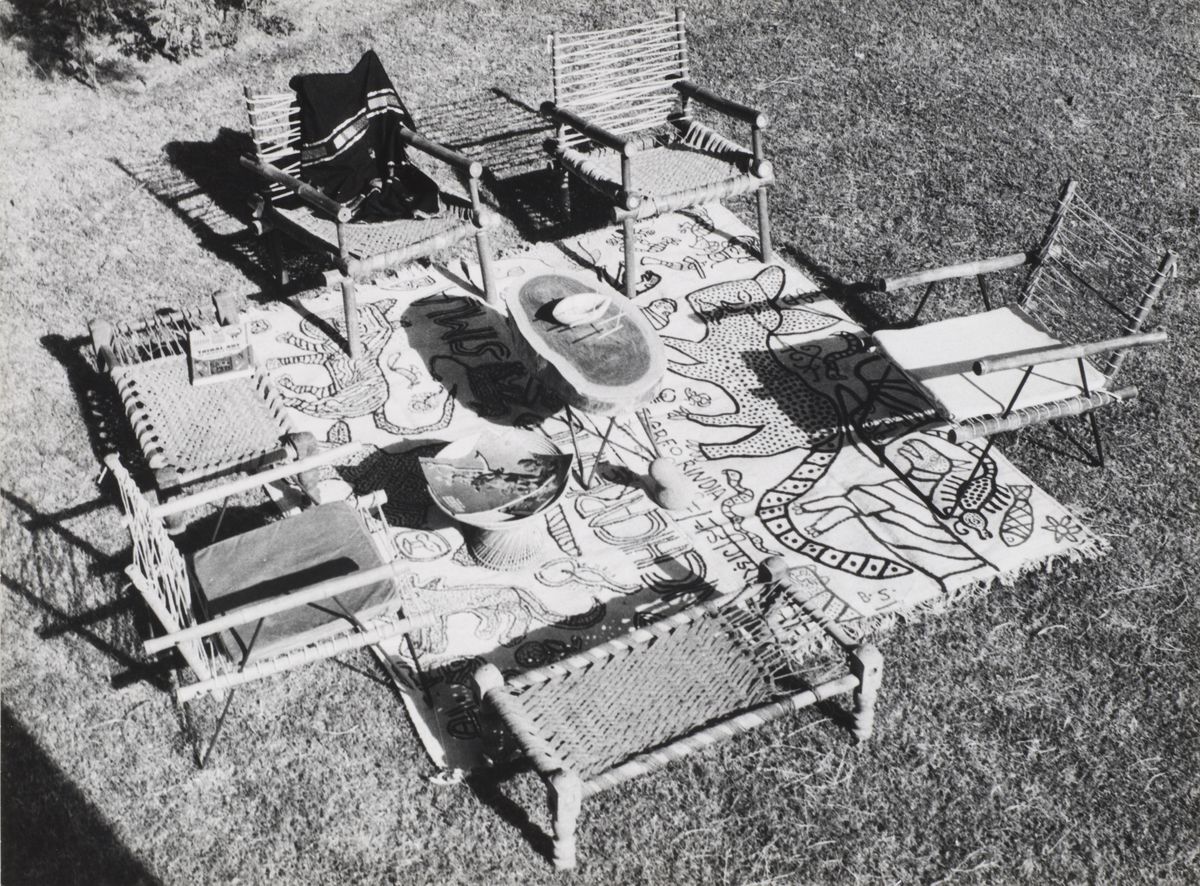

The large-scale production of housing, elementary and high schools, colleges, libraries, dispensaries, cinemas, markets that went on in tandem with this civic architecture demonstrate Jeanneret’s deep engagement and commitment to Chandigarh. It is often said that architects simply design buildings, while people shape them through their use. However, Jeanneret was bound to the ensembles in ways beyond the creation of architecture: he explored variants of furniture with which he later infused life and activity in the buildings, revealing the earlier association between Jeanneret and the furniture designer at the Paris atelier, Charlotte Perriand. The introduction of custom furniture to public, civic architectural types and even private villas not only served an immediate need to accommodate functions in the city but also provided livelihoods to the carpenters, masons, technicians, and displaced craftsmen from across the borders of Lahore and West Punjab in the wake of India’s partition. The housing projects are especially fine examples, featuring built-in cupboards, closets, seats, benches, display and lighting alcoves, concrete uplighting, and terracotta screens. These served as embellishments to the modernist buildings otherwise bound by straight lines, right angles and minimal use of material.

Unknown photographer, view of a chair designed by Pierre Jeanneret, Chandigarh, India, 1958-1979. Gelatin silver print, 8.5 × 5.7 cm. ARCH402419, Pierre Jeanneret fonds, CCA Collection. Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret.

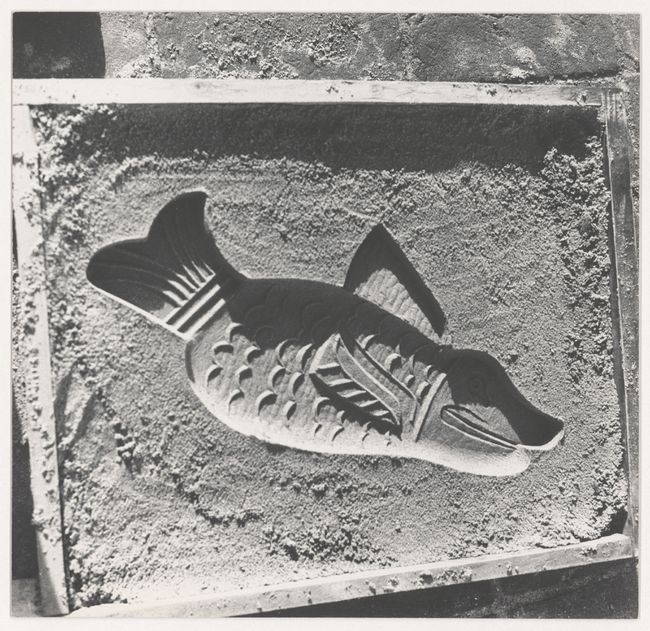

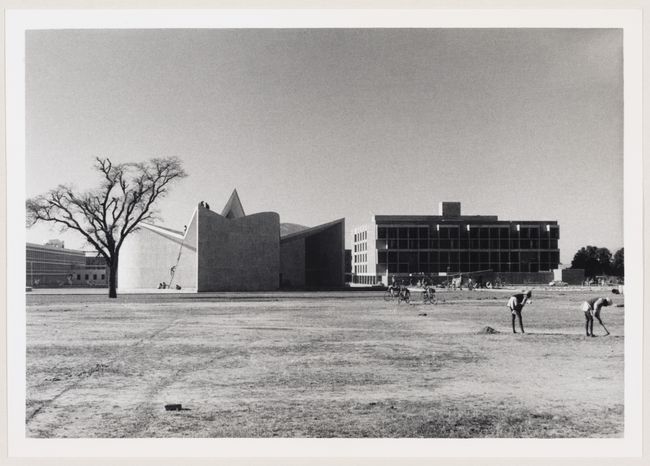

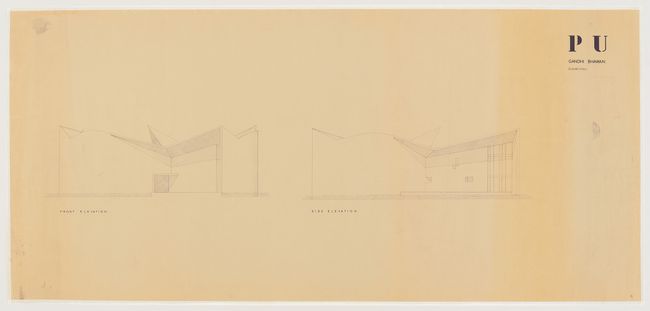

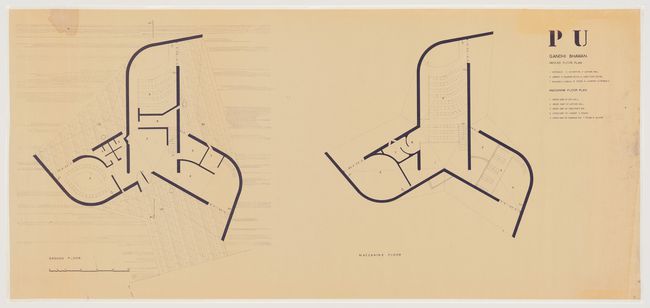

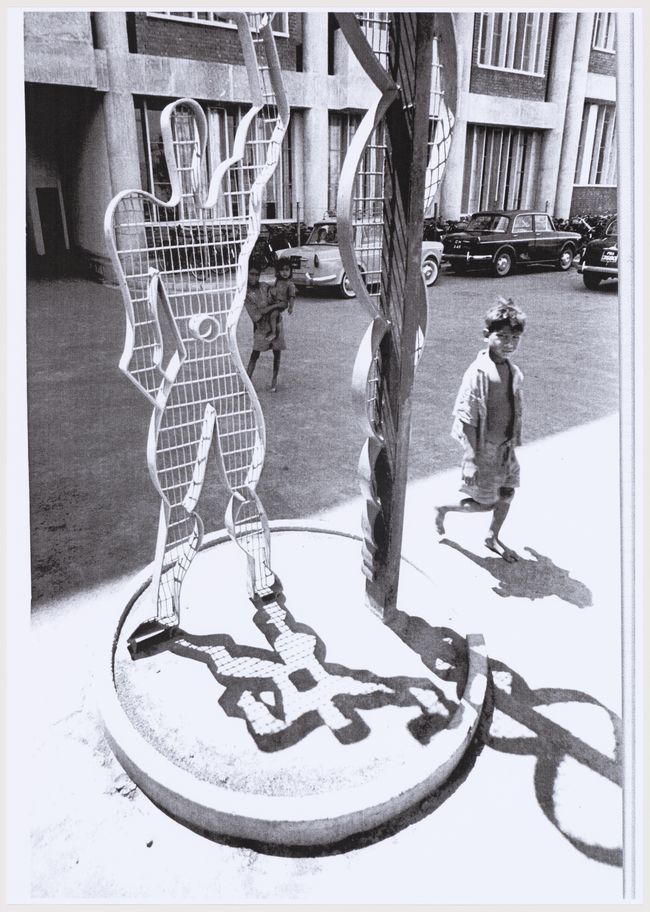

The motifs found in his functional ornaments had been neatly captured by Jeanneret’s cameras during weekends exploring the hinterlands of the surrounding villages and hamlets in the states of Punjab and Himachal. Symbols in wet concrete of the modular man, birds in flight, twin camels, human hands, leaves, fish, serpents, and other Indian motifs were the art in architecture of the city. The Gandhi Bhawan, the icon of the Panjab University Campus for which Jeanneret served as the chief architect, features a white pebble exterior panel cladding that distinguishes it from surrounding red sandstone buildings. Its roof form brought natural light into the interior, and its three-winged structure was inspired by the pinwheel—it is like a lotus standing in a pool of water. Several models of the roof and skylight inform a final version developed by Jeanneret under the mentorship of Indigenous craftsmen, carpenters, and masons, among architects and engineers.

Pierre Jeanneret, elevations for the Gandhi Bhawan, Punjab University, Chandigarh, India, circa 1962. Diazotype on paper, 47.2 x 102.1 cm. ARCH268865, Pierre Jeanneret fonds, CCA Collection. Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret © CCA

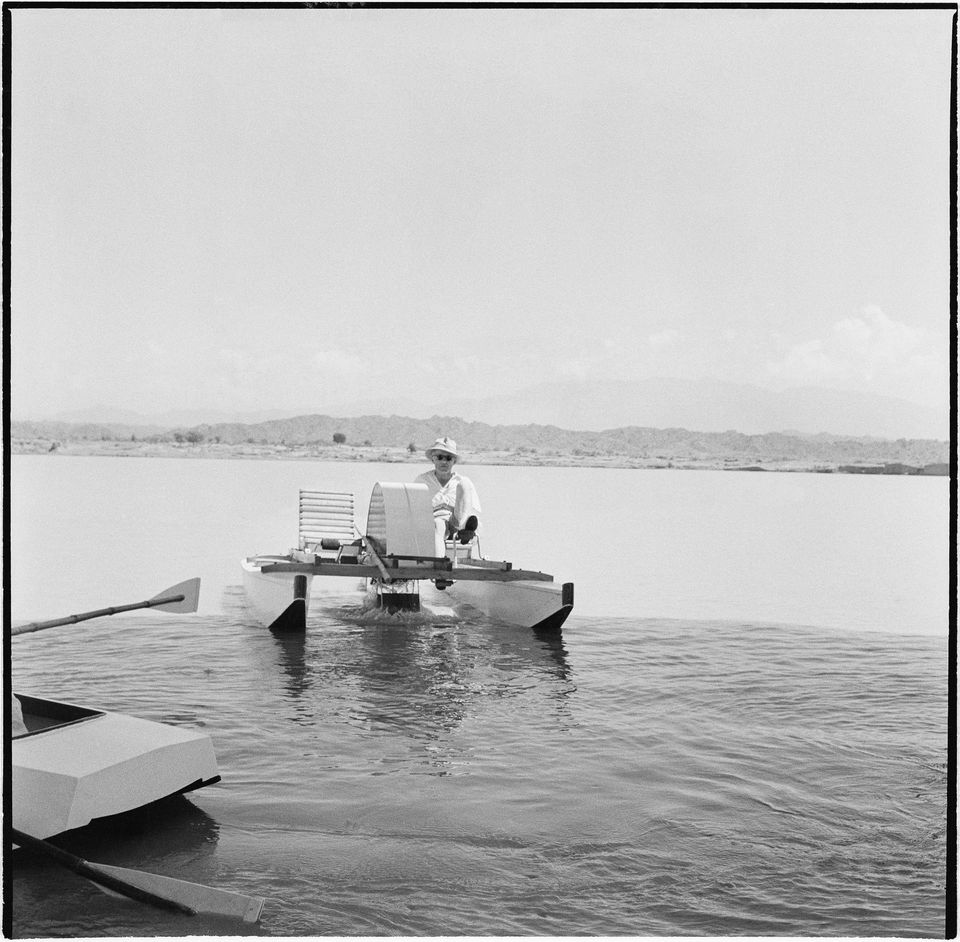

The archive also reveals to a large extent that Jeanneret had developed his own timetable for his life in Chandigarh. Tiny scribbles and notes on the backs of personal photos, picture postcards, and diary pages reveal the lifestyle of a bachelor who spent more than a decade and a half with the extended family of his friend (and cook) Bansi. Though his weekday mornings were utilized to develop the city fabric alongside Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, assisted by a team of young energetic Indian architects, and the afternoons would be filled with site work, on Sunday’s, Jeanneret would spend his afternoons weaving dhurries and baskets, fabricating cots and hammocks from rope and locally made cotton, and making boats with Bansi’s family—in a way, small joys that celebrated India’s recent 1947 independence. Jeanneret was open to imbibe in and embrace the culture of Punjab.

Unknown photographer, street with Modulor Man sculpture in Chandigarh, India, 1950-1970. Gelatin silver print, 29.6 x 21 cm. ARCH279613, Pierre Jeanneret fonds, CCA Collection. Gift of Jacqueline Jeanneret.

A boat club envisaged as a private yacht club was designed and built next to Sukhna Lake, where Jeanneret and Le Corbusier would test homemade boats. Tucked into the ground so that the visitor’s view of the lake remains unobstructed, the boat club deck is approached by a cantilevered staircase held in place with a river stone wall and a simple black straight-lined railing—these two elements are repeated throughout the city like an aesthetic legislation. The undulating glazing that follows the curved plan of the boat club lounge, the concrete uplights that provide subdued lighting into the evening so as to not disturb migratory birds, the rubble embankment of the Sukhna Lake edge from which stairs lead to the boats, all echo the story of how man, nature, and modernism can come together to create a timeless architecture and spirit of a place. It was into Sukhna Lake that Jacqueline Jeanneret carried Pierre’s ashes, all the way from Geneva, to fulfill his last wish to be laid to rest within the capital city; a guardian to his own collection.

Sangeeta Bagga was in residence at CCA in June 2019 as part of Find and Tell, a program that promotes new readings that highlight the intellectual relevance of particular aspects of our collection today.

Related residency