Haven, a conversation about money and architecture in Argentina

Martin Huberman speaks with Alejandro Bercovich and Pablo Touzón

The first research focus of the CCA c/o Buenos Aires program aims to establish a correlation between architecture and a strange financial reality that, for decades, has pervaded in Argentina—a strange financial reality that is ordered or disordered on a double monetary system in which the Argentine peso and the US dollar seem to be bound by a stormy relationship.

Architecture as a commercial operation, as in the purchase and sale of real estate and homes, is carried out in dollars—as if it were a commodity of international exchange—while the rest of the economy, such as wages, salaries, material goods, food, expenses, taxes, etc. is carried out in pesos. This is because those who have disposable income save in dollars. Originally, the dollar was part of the banking system, however, the successive crises and a growing lack of trust in the banking system led people to bypass formal structures by depositing cash in safe deposit boxes, in cuevas1, or in their own homes. In this case, both personal homes and investment property have functioned as havens for financial value—and this is how the extraordinary link between architecture and the dollar was forged. The architect, an accomplice to this reality, knew how to navigate these informalities by using mechanisms that enabled them to meet demands while at the same time generating more work. The most well-known of these systems is the fideicomiso, a local expression of trust deeds that was adopted from inheritance law, adapted to building production, and subsequently became a coveted refuge for savings after the crisis of 2001. This form of trust existed during the Roman Empire and is traditionally a tool through which a transfer of assets is structured between parties, usually family members, without being tied to the professional activities of the people involved. In the building development context, it allows investors and trustors to transfer money or land to a trustee, an architect, or a limited liability company that act as a developer, with the aim of carrying out a project that generates benefits—in this case, building units that are distributed among the beneficiaries at the end of the journey. In part, the success of this legal tool in the local context lies in its ability to protect assets and parties. But, mostly, it succeeded as a result of its ability to remain invisible to regulatory bodies.

To analyze the context in which architecture took its leap towards becoming a financial phenomenon, Martin Huberman (MH) spoke with the economic journalist, Alejandro Bercovich (AB), and the political scientist, Pablo Touzón (PT). With their help, we strive to demarcate the power relations that, for decades, have permeated the professional work of architects.

-

Commonly known in Argentina as caves, cuevas is the popular name to describe informal businesses where foreign currency is bought and sold in a parallel market. They are usually offices, financial entities, and other exchanges that function outside the formal system. ↩

- MH

- What led to the crisis of 2001?

- PT

- A scarcity of dollars in the economy was a recurring factor in the twentieth century. But the obsession that ordinary people have with the dollar is something much more recent. A change in the relationship between economic and social structures began in the 1970s and deepened as a result of the military dictatorship.1 Convertibility was not only an economic policy, but it was also the basis of a new political and social order, during which the obsession with the dollar subsided.2 And that’s why politics, the economy, and the social sphere exploded together at the end of December 2001.

- MH

- So, let us imagine the last hundred years of the Argentinian economy as a moderately steep slope, with some irregularities, just like the rest of the world…but with stable growth—until the dictatorship exploded.

- AB

- When Argentina was screwed over.

- MH

- Exactly. We can see the start of a period with ups and downs; the economy falls with hyperinflation in the 80s, during convertibility it rises again, only to fall precipitously during the 2001 crisis. A financial crisis, an institutional crisis, bank runs, violence in the streets. How did it happen?

- AB

- Well, the problem with convertibility is that it maintained a fixed parity in a context in which the rest of the world was not fixed. But it made it possible to buy houses, have savings in dollars, it turned the wheel of credit. It was a formula that seemed to provide a magical solution to the lack of currency in Argentina.

-

National Reorganization Process is the full, formal name of the military dictatorship that governed Argentina between 1976 and 1983. ↩

-

Convertibility (1991-2001) was a period in which the value of the Argentine peso and the American dollar were equal, generating monetary stability that put an end to a period of hyperinflation and created political stability. ↩

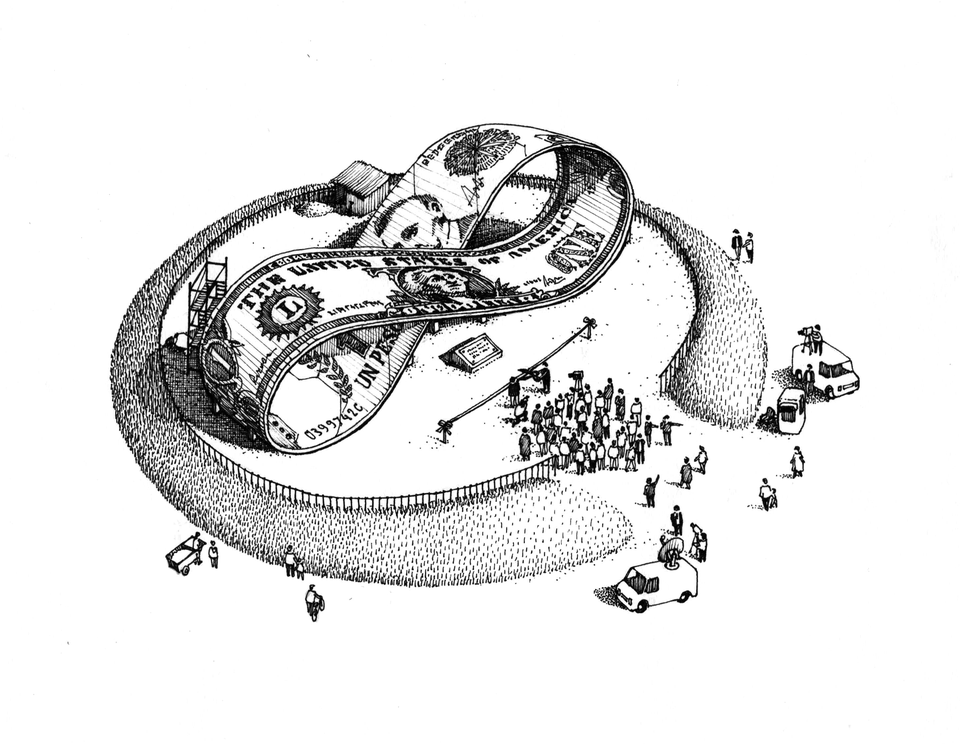

Although it has felt like a long time, the tumultuous relationship between the Argentinian currency and the US dollar only took shape over the last fifty years, extending its influence beyond the financial world to flood various aspects of daily life. The 1990s provided a framework for testing a magical solution called “convertibility,” a policy under which politics, the economy, and society came together to revere an inexplicable parity between the dollar and the peso which temporarily seemed to reassure many. Illustration © Manuel Ignacio Nesta

- PT

- Further, there didn’t seem to be an electoral political position that would denounce convertibility and win votes. It was as if everyone were totally unethical. During the crisis, the political class was accused of committing a sin that was actually shared by all.

- AB

- In the demonstrations that emerged from the crisis, we saw that one of the main demands was for banks to give people back the money that they had deposited in dollars. In reality, the demand was not, “We want our dollars,” but rather, “I want to preserve my purchasing power.” In a conflict such as this, what is at stake is the notion of savings security.

- MH

- I am interested in investigating the link between architecture, or bricks and dollars, as havens for protecting people’s savings.

- AB

- Gaggero and Nemiñia are two investigators that found the very first ad ever published in a newspaper that advertised the sale of property in US dollars, it was for some chalets to the north of Buenos Aires. The ad is from 16 July 1977. In other words, some people think that, in Argentina, houses and apartments have always been sold in dollars, but that’s not the case. The practice started on 16 July 1977.

- PT

- One could think that the dollar functioned like a bribe in Argentinian society, which no longer had any real opportunities for upward social mobility. In recent decades, the only way to maintain purchasing power has been through leveraging delays in the exchange rate and avoiding inflation runs. In the context of inflation, the treasured and stable US dollar became more profitable over time, especially in parallel markets.

- MH

- It goes back to the saying that we have, “Someone who bets on the dollar never loses,” which unfortunately has rung true in recent years. While governments did everything they could to keep the peso stable, even denying double-digit annual inflation, beneath the surface, the gap between the peso and the dollar kept growing. When the parity between the peso and the dollar remains stable over a long period of time, the economy tends to rebound, as was seen during the recovery that followed the 2001 crisis.

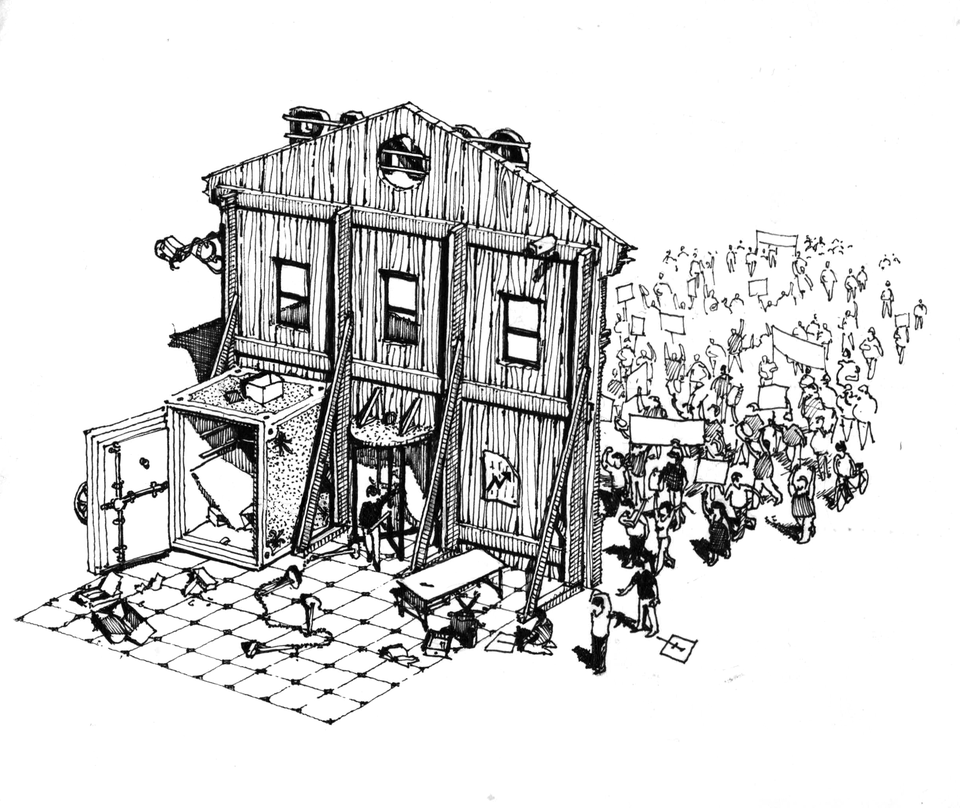

The inevitable and drastic devaluation of the peso brought an end to convertibility and pushed depositors to literally run to the banks to try and rescue their savings. In response, the banks closed their doors to those whose assets they had promised to house. The contrast between the historicist facades and their impenetrable status denotes the abrupt end of a relationship that took almost a century to forge. Illustration © Manuel Ignacio Nesta

- AB

- There is something interesting in the link between savings, investing, and the lack of trust towards banks. As economists, we have learned that savings equate to investments in countries where the economy more or less functions as it should. Basically, there are people who have money left over, they put it in a bank and the bank, in order to give a return to its clients, gives the money to someone else who is going to get a higher return on the investment. The bank then takes its cut, and it transfers the funds from savings to investments, from the client that had surplus money to another that needed capital, to carry forth an idea. In the case of architects, the idea is a project. And this system is what’s broken in Argentina. And since it’s broken, it was replaced by a tendency to hoard dollars. Dollars are not only used to pay foreign debt, among other things, they are also necessary to buy and sell property.

- PT

- The first movement of Kirchnerism1, supported by commodity prices during that decade, sought to fulfill dreams in terms of human rights and individual purchasing policies, hinging on the successes of previous presidencies. However, it was not just about populism. For those who could not afford to hoard dollars, consumerism was the Argentinian pact that replaced upward social mobility. In Argentina, you could buy a house in cash and a cellphone in fifty installments. I would say that it became increasingly more difficult to obtain the material possessions that are traditionally required for upward social mobility.

- AB

- Beyond the richest 10% of the population, which has access to other ways of protecting its savings and investing, others have no means by which to enrich themselves. The middle class looks to their home as a way of increasing wealth. And the only way for a middle-class family to increase its wealth is by moving to a bigger house, buying a durable asset. The lower classes, on their part, have nothing. They live entirely day-to-day in a borrowed, rented house. The structural problem of that period, in which there was a strong redistribution of income that made the economy grow at 7-8% per year for five or six years, was a disconnect between the distribution of income and the creation of wealth. And at the heart of that problem is housing, because those who could afford to buy things in installments consumed more; many more air conditioners were sold, people were happy with their air conditioners, but when that process ended in 2015 and wages collapsed, there were families that were…

- MH

- They had nothing else but an LED TV and an air conditioner…

- AB

- They had a lot of knickknacks, but here wealth is made manifest in the form of a house. Apartments are apartments, but they are also safety deposit boxes. The other day, I heard a story about some apartments that were designed to the value of what a safety deposit can contain…It is like a hyperbole of the ridiculousness of using a house as an asset refuge, it completely distorts it. That is why there are houses without people, and people without houses. In addition, we have a problem in that apartments function like banks, it is a problem that governments have tried to address from different angles, but without success. These are all examples of fulfilling a task that would normally be performed by a banking system in a normal country. It is not the architect, it is the bank.

-

Nestor Kirchner’s presidency (2003-2007). He was later succeeded by his wife, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who was in office for two consecutive terms, 2007-2011 and 2011-2015. This period is known as El Kirchnerismo. ↩

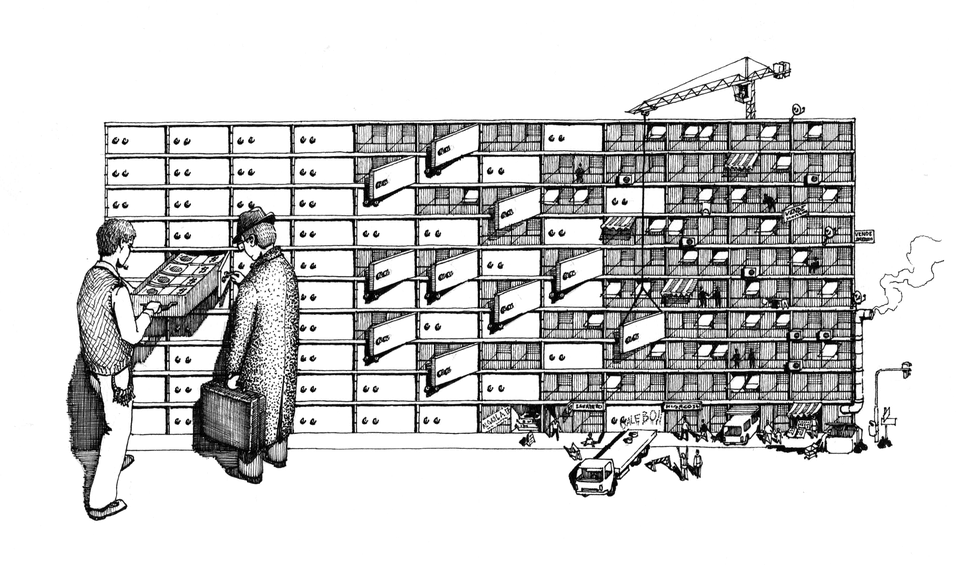

When confidence in the banks was shattered, the public turned to material brick as a refuge for their savings. This speculative perspective reduced architecture to a mere commodity for the safekeeping, spending, and transaction of funds. The recourse to architecture as a focus of investment consolidates an old figure within the discipline, the architect-developer, who is responsible not only for designing buildings but also for conceiving lucrative ventures for investors. Illustration © Manuel Ignacio Nesta

- MH

- To resist creating systems that enable one to survive—I call that creative resilience. Popular assemblies, bartering, and trusts (the fideicomiso) emerged at the same time as structures of resilience. But the fideicomiso was doubly successful. It went from being a mere refuge for money to becoming an investment instrument with returns of up to 20% or 30% in two years.

- AB

- Those returns leave people out. Because no one has that many dollars unless they are an investor. Considering property as having exchange value rather than use-value transforms it. I imagine it must have an equivalent in construction where the objective is to demonstrate a higher return for the investor.

- MH

- A developer told us that the initial purchasing price for an apartment for an intimate circle of investors had been 55,000 US dollars. Two or three years later that same apartment was selling for 85,000 to 90,000 US dollars.

- AB

- It inflates precisely because it is used to store value, not because there are expectations that this neighbourhood will improve, or that people will have a better quality of life there…It is not a phenomenon that generally happens in other places. I think that is the principal challenge: to first, ensure better access to housing; second, to eliminate the macroeconomic obstacle, which makes dollars necessary to sell houses; and third, to avoid apartments becoming more and more like shoe boxes.

- MH

- If you analyze that period of almost twelve years, 2003-2015, of architecture as a tool for speculation, you will come across the rise of the studio apartment, a typology that in architectural terms generally equals zero. The twenty-one square metre studio apartment promulgated by the New City Building Code is a result of that period.

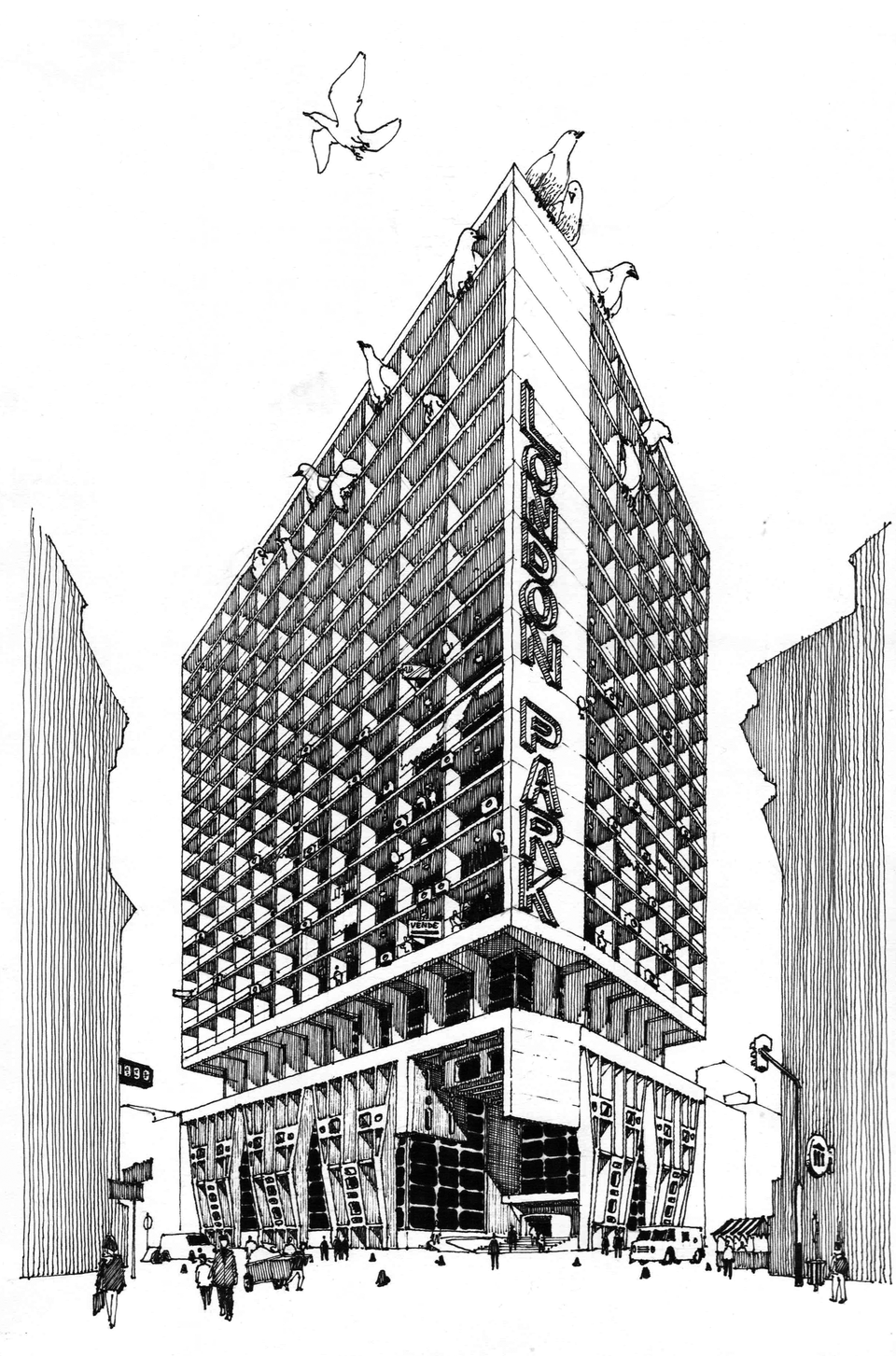

The one-room apartment, a living unit that meets minimum requirements established by the building code, has become the typology that guarantees the greatest amount of mobility in a market of moderate resources. In the collective unconscious, residential buildings now provide a sense of security in saving that was previously offered by the banking system. Architecture leaves its poetic commitment to the service of human habitat to serve money instead. As a result, housing has become a deregulated commodity accessible to a small circle of people. Illustration © Manuel Ignacio Nesta

- PT

- What happened in the local shanty towns known as villas? How was value conserved for the poor there? What other place is more typical of social mobility than that?

- MH

- During this period, enormous growth took place in the shanty towns, which due to their proximity to sources of money and work also became financial territories. As I understand it, Villa 31 grew as a result of internal and local developers. I am not just referring to the romantic image of someone who builds their house with their bare hands. There is also an investor that expands developments and speculates on inflating the rent for those who already live there. The villas gave rise to towers of studio apartments. Speculation traces a link between the formal, a trust in any neighbourhood of the city, and the informal that took place within the villas. The difference is that in the villa there was a single investor, it wasn’t a joint venture, and generally, in the villas there are entire families that live in these studio apartments under cramped conditions.

- AB

- And it all took place in pesos. That is a very striking difference, that these properties were marketed in pesos. Why? Well, because there was a lack of access to the dollar market and because people were resigned to the volatility of the local currency. Everything was much more focused on the short-term, less regulated, and yet people were still gambling in order to invest.

- MH

- Not long ago, we discussed these issues with the architects Javier Agustín Rojas and Rodrigo Kommers Wender who are here in Buenos Aires with us. One of them raised the point that a trust was a way of generating work after 2001, but I don’t know if there was a reflection on the following questions: What do we do as architects? Who do we work for? Javier quoted Manfredo Tafuri, who says that architects work for the princes of every era. Who would hire us, if not the government, in a country where there is no growth in purchasing power? That being said, what do you, a political scientist and an economist, see as possible alternative scenarios for architects?

- AB

- It would be necessary to consider to what extent capital mediates all of our social relationships. Many more homes are needed than what can be built by the trusts belonging to people who have been able to save dollars. It’s not necessarily the government that must hire the architects, but it’s the families themselves who need housing and, and they may organize themselves, perhaps with the help of the government, or through new organizations, generating funding schemes for the construction, in pesos, with their own income.

- MH

- Rodrigo and I were wondering if it would be possible to disassociate the home from its reference as a safe deposit box for savings, or is this a cultural issue?

- AB

- Well, for that there are specific tax tools, but there is also evasion. Whoever has a property in their name should pay a much higher tax for the second property compared to the first one, then it would dissociate one thing from the other.

This is an excerpt from a conversation that took place during You met me at a very strange time in my life, the launch of CCA c/o Buenos Aires.

Related articles