You met me at a very strange time in my life

Martin Huberman sets a scene

When everything crumbled

When people shouted all the politicians out

When the banks eroded their only asset

When exchange went back, way back, to simple trade

When decisions were made in the streets at public assemblies

Why did I decide to become a financial institution?

Why did I choose to follow the money?

Why did I become the bank?

Isaac Newton’s third law of motion says that if a body exerts a force or action on another, the second body will generate a force, called a reaction, of equal magnitude but opposite in direction. This law outlining the basics of classical dynamics could also describe the economic and social behaviour that regulates crises and, in reaction, post-crises. Like a reaction engine, every period of crisis is followed by a period of equal force and magnitude in economic boom and social movement. It happened in the United States after the Great Depression, then in “The Glorious Thirties” in France and other European countries after undergoing twenty years of wars, and, finally, after the global crisis of 2008.

In Argentina, the vernacular version of the formula is enhanced by the predictability with which this terrible swing, of indeterminate duration and impact, occurs every ten years. Here, people have through the ages acquired survival strategies to deal with the fallout that are based on the powerful motto “every man for himself,” laying the bases for creative systems that help to establish a new social order.

The crisis that erupted in December 2001 in Argentina is perhaps the most dramatic and deep-seated in its history, and the one with the greatest impact on the social fabric of its cities. From 2001 to 2003, the country was immersed in an unprecedented institutional and representative vacuum that served, along with other mobilizations, as the baseline for local assemblyism as a trial for a new form of governance. At the same time, an idea was outlined to replace economic activity based on unlimited consumption with bartering practices that created a fragile new financial system, almost ancestral in nature, as the national economy unravelled in a stream of government bonds. Mortgage credit systems were undermined by bankruptcy and inflation, and traditional access to home-buying became almost impossible. Financial activity collapsed due to the sudden drop in confidence in the banks, partly responsible for triggering the debacle by preventing their clients from accessing their savings. Insecurity seized the streets with new forms of crime and fuelled the proliferation of organizations that proposed seclusion as a way of mitigating fear. At the same time, informal residential developments in the city and its suburbs increased their population by between 50 and 70 percent, taking in both migrants seeking refuge in the cities and vulnerable sectors driven to homelessness by the crisis.

During the subsequent rebound, as the period of economic boom between 2003 and 2008 is popularly known, a general policy of laissez-faire prevailed, seeking rapid economic growth while reshuffling institutions. The social climate, which in the heat of the crisis had advocated a drastic change in political and social structures under the banner of cooperative, collaborative post-capitalism, was slowly seduced once again by the apparent comfort of deregulated super-consumerist late capitalism.

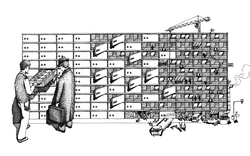

Architecture and construction, hard-hit even in the years before the crisis, were reduced to alternative models of survival. The sudden shift from complete stagnation to the sector’s explosive resurgence as the result of fresh confidence in construction as the only sustainable future investment, saw the discipline become a financial laboratory to safeguard savings and construct new ideas of security. Accordingly, with a minimum of urban and mortgage planning guidelines, the transformations effected in the profile of the city and its peripheries took place almost exclusively in the private sector. As gated districts multiplied, emergency satellite neighbourhoods grew and forged self-organized direct links with sources of investment and money. The slum as a social sponge, the dwelling as a way of saving, the architect as a developer, and private districts as a new ideal of suburban life are some of the most marked features of the period.

This period of “unlimited” deregulated growth for Buenos Aires in terms of its built environment generated an architecture that articulated social relations and extravagantly danced between the formal and the informal. The discipline adopted a strange unconditionality towards money, becoming an almost self-sufficient financial body. A closer study ought to be made of the capacity of architecture to arbitrate in the urban and social conflicts that emerged with the increased insecurity that marked the period, and of the architecture itself that transcended its projective structure and became organic in its contemporaneity, even at the cost of a social perspective.

You met me at a very strange time in my life is the first program of CCA c/o Buenos Aires.

Related articles