Foreign Bodies, Three Hills, and a Hospital

Rachel Lee, Arnold Mkony, and Monika Motylinska interrogate the neocolonial origins of Bugando Medical Centre

Bugando Medical Centre, a regional teaching hospital, stands on the crest of a hill in Mwanza, a port city built into the undulating boulder landscape of the southern shore of Lake Victoria, Tanzania. Constructed in the early 1970s with funding from the German state and a Dutch charity, under the auspices of the Tanzania Episcopal Conference,1 this large-scale healthcare infrastructure clearly demonstrates how development aid can manifest. Furthermore, the input of foreign design and construction knowledge significantly outweighed that of local expertise: the hospital was conceived of by the German firm Lippsmeier + Partner Architects (L+P) and built by the Israeli company Solel Boneh. This asymmetry in sources of funding and know-how could be understood as evidence of the pervasiveness of neocolonialism that materialized in the Bugando Medical Centre, even a decade after Tanzania’s independence from British occupation.

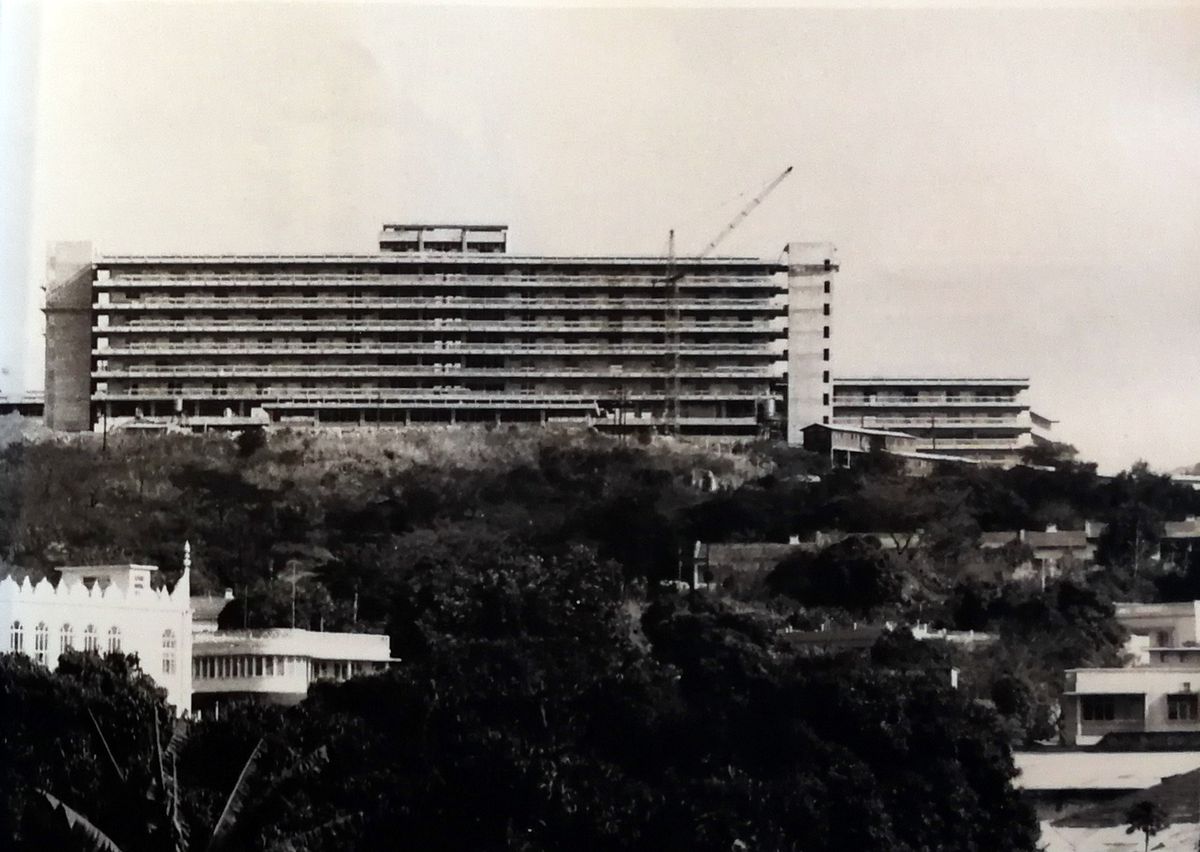

The striking appearance of the hospital—a massive twelve-storey concrete slab—renders it highly visible from within the surrounding urban environment. Its visual expression is dictated by bands of cantilevered exterior walkways that circumscribe the main building, with offset railings that convey lightness all while the floor beams puncture the facade in a decorative way. An array of smaller pavilions surrounds the main building, connected by covered passageways along the main circulation axes. The hospital could be mistaken for a 1960s-era modernist building somewhere in London—or perhaps in Sao Paulo, Cape Town, or Tokyo. Within the undulating landscape of Mwanza dotted by much lower structures—Swahili houses with their square layouts and hipped roofs, art deco buildings built by South Asian migrants, colonial edifices, “tropical modernist” architecture, locally built office blocks, and hotels built by Chinese construction companies—the hospital emerges like a foreign body in an unfamiliar ecosystem.

-

The project was funded by Misereor, a German Roman Catholic aid agency founded in 1958 with headquarters in Aachen. It conducts projects in Asia, Africa, Oceania, and Latin America with the aim alleviating poverty. For the Bugando Medical Centre project, Misereor partnered with the Tanzania Episcopal Conference, which is the conference of Roman Catholic bishops in Tanzania, founded in 1956 with headquarters in Dar es Salaam. ↩

In order to analyze a potentially neocolonial, foreign body from different perspectives, this research brings slides and project documentation from the Georg Lippsmeier Collection into dialogue with both colonial images from German archives and fieldwork photographs.1 The method intentionally reconstructs the viewpoints of the Lippsmeier slides, but also shifts the gaze toward what was not visible or had been consciously excluded from the frame of the camera lens. This approach both highlights the complexities of the project and is an attempt to reckon with our positionalities as unmistakably “foreign” (Scottish-German and Polish-German) and “non-local” (a speaker of a Swahili dialect from Dar es Salaam) researchers.

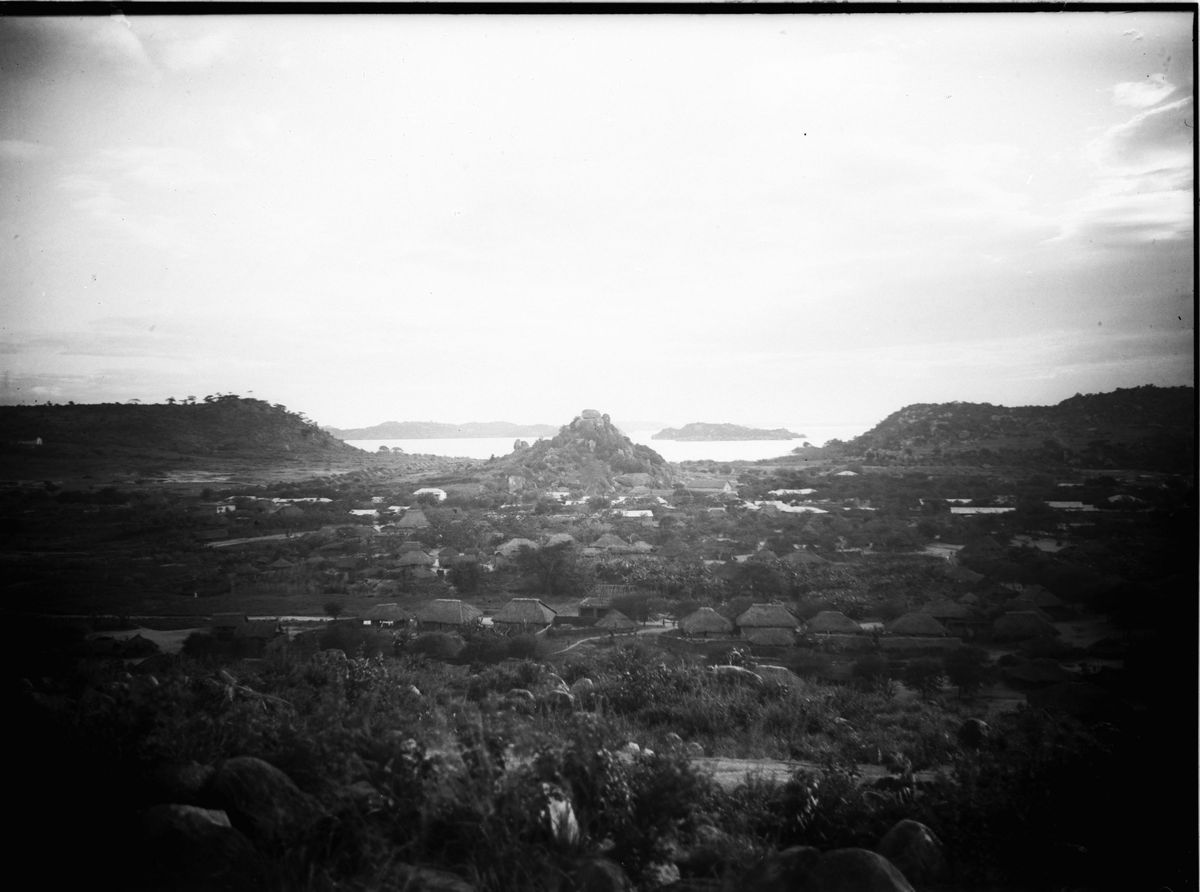

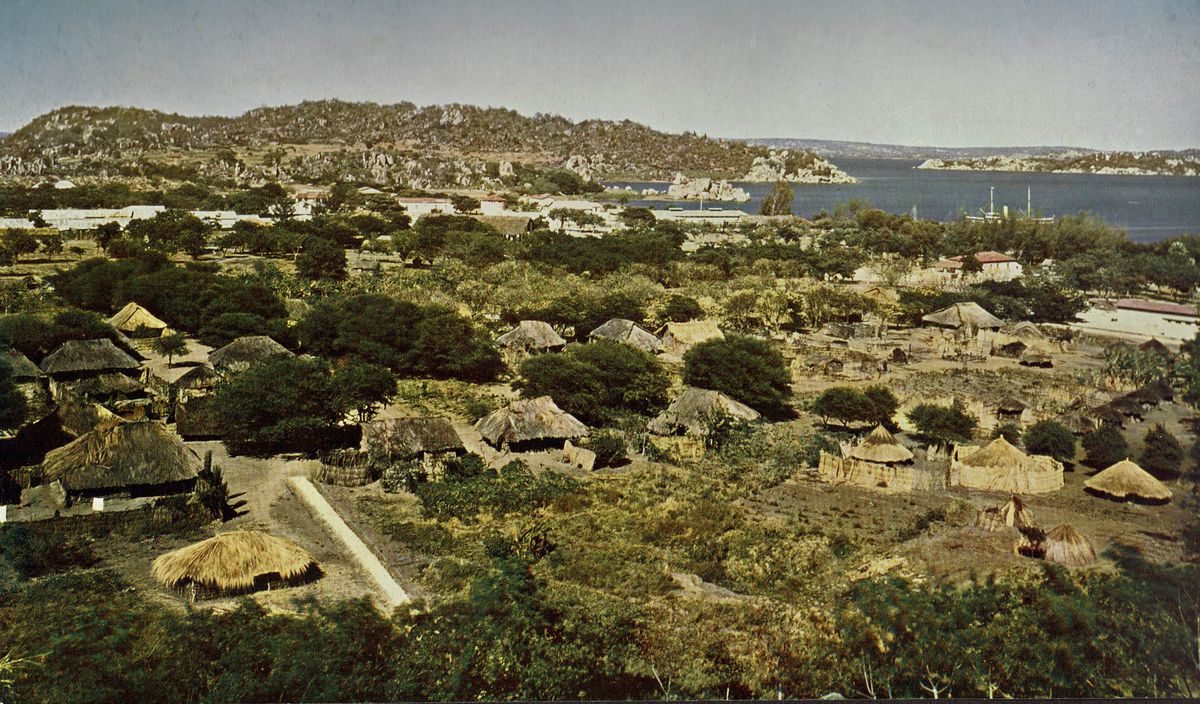

Mwanza is situated at the crossroads of historically important trade routes that traverse the Great Lakes Region. In the early twentieth century the city was forcefully incorporated into the colony of German East Africa but, in contrast to the coastal cities of Dar es Salaam or Tanga, the human presence of colonial power was limited to a small number of military and administrative officials. Mwanza is barely documented in collections of colonial photography, only occasionally appearing through certain recurring motifs of rock formations typical of the local landscape, as well as through scenes of markets and colonial infrastructure and buildings, including a hospital.

-

This text is part of a research initiative focused on the social infrastructure projects of Lippsmeier + Partner and the Institut für Tropenbau. It relies on archival material and witness interviews, undertaken during fieldwork in Dar es Salaam and Mwanza, 1–14 February 2020. ↩

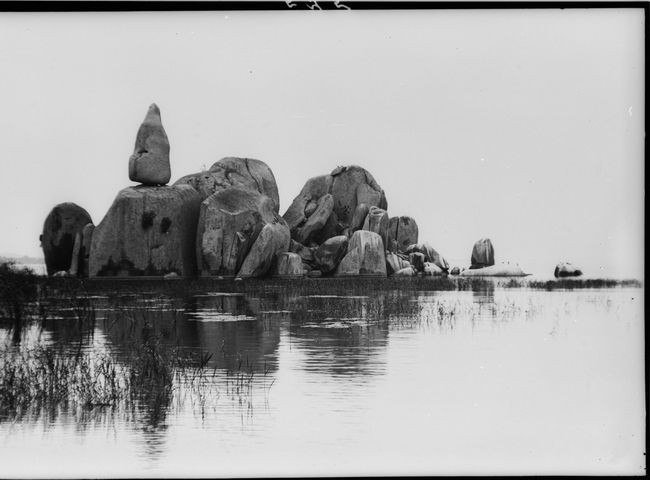

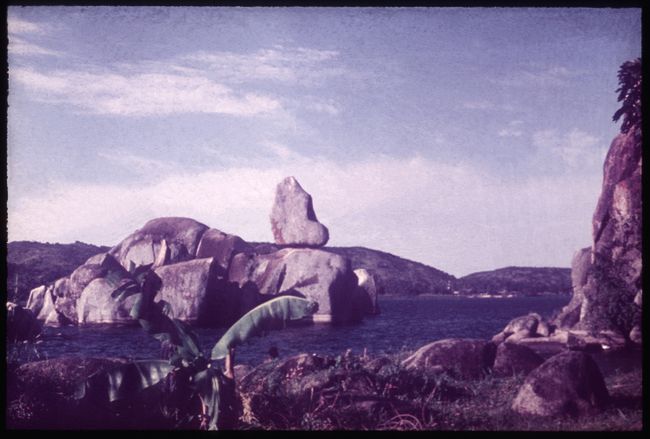

Some of these motifs resurface in the slides of the Georg Lippsmeier Collection, and yet without an understanding of the particular historical context in which the slides were taken, it would be difficult to distinguish between colonial and postcolonial images. For example, to stake their colonial claim, the Germans assigned the name Bismarck Rock to an iconic boulder formation in Mwanza. As one of the city’s landmarks, it was also documented by Lippsmeier’s team. Today, although no colonial references are visible in the area, the name given by the Chancellor of the German Empire continues to defile the site, even if groups in both Germany and Tanzania have recently campaigned to have it renamed.1 In what could easily be interpreted as a neocolonial claim, a mock-up of this rock formation was erected in 2015 in Würzburg, Mwanza’s partner city in Germany.2

-

Ramona Seitz, “Koloniales Erbe von Tansania und Deutschland: Der Bismarck Rock in Mwanza und sein Nachbau in Würzburg. Botschafter von Tansania fordert Umbenennung” [Colonial heritage of Tanzania and Germany: Bismarck Rock in Mwanza and its replica in Würzburg. Ambassador of Tanzania demands renaming], RiffReporter, 22 December 2020. ↩

-

Stadt Würzburg, “Ein Bismarck Rock für Würzburg” [A Bismarck Rock for Würzburg]. See also: TVMainFranken, “Mini Bismarck-Rock Wahrzeichen im Mwanza-Garten” [Mini Bismarck Rock Landmark in Mwanza Garden], 10 November 2015. As stated on the website, the total cost of the mockup landmark amounted to EUR 29,000. ↩

Jaeger and Oehler, Bismarck Rock, Mwanza, Tanzania, ca. 1906–1907. 13 x 18 cm. 012 -1065 -12, Picture Archive of the German Colonial Society, University Library, Frankfurt am Main.

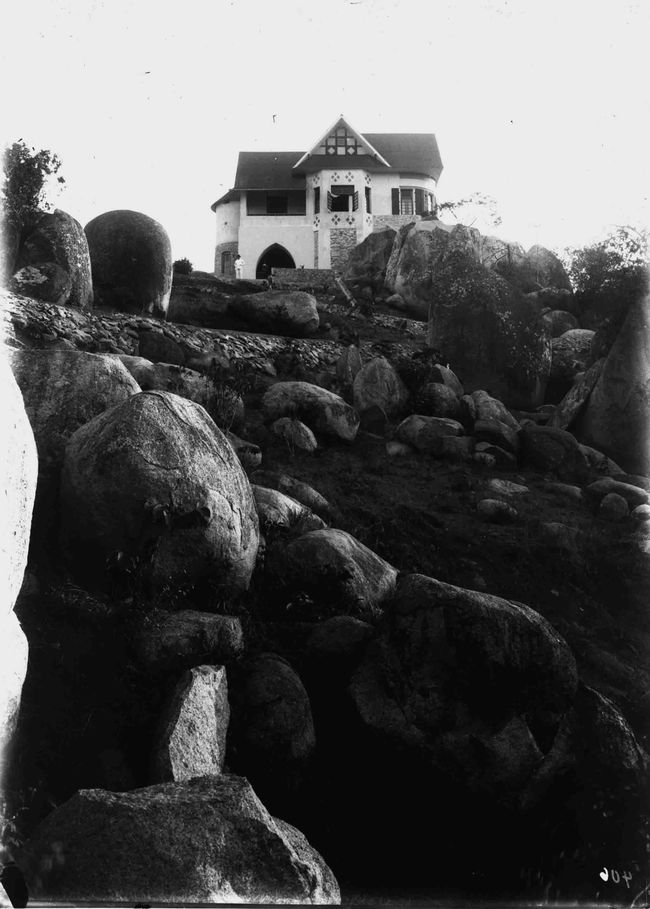

Aside from Bugando, two other hills dominate Mwanza’s cityscape and are both occupied by buildings of German origin; and in both cases these buildings are colonial vestiges. First, to the northwest of the hospital and above the central business district stands a colonial villa, known as Gunzert House, built around 1910 as the residence of a county commissioner. The villa has been abandoned for decades and is, according to the pujari (priest) at the nearby Sri Swaminarayan Mandir (Hindu temple), widely believed to be haunted—though he has lived in Mwanza for forty years, he has never ventured up the hill to visit it. Today, a notice at the villa’s entrance states that it is being converted into a museum and cultural centre, apparently with funding from the German Foreign Office. Even though the hill is surrounded by a bustling market, the colonial structure is disconnected from the urban fabric both because access is controlled by guards and because its elevated position forces visitors to undertake a steep climb. This inaccessibility—intentional in the colonial period, in order to control and dominate the surroundings—now proves to be a major obstacle to ongoing conservation works. And yet from the summit of the hill, the villa’s grounds offer expansive views across the city, including of the hospital, perched conspicuously atop Bugando Hill.

A second hill to the north of the hospital was once the centre of German colonial governance in Mwanza. Its summit was occupied by a boma (a citadel), which likely contained government and military offices, and two watchtowers. The same buildings are now used by the Tanzanian government and the site includes the residence of the Regional Governor. An image showing the citadel in the Georg Lippsmeier Collection is evidence of a curiosity toward this German colonial architecture in Mwanza. Perhaps more interesting, however, is that a hired photographer, Meinrad N. Filgis, used the citadel as a location from which to document the construction process of the hospital. This image of the hospital, seen from afar, likely from the southwest watchtower on the citadel, features prominently at the beginning of the photobook that Filgis produced.1

-

Meinrad N. Filgis, R.C.T. Hospital Mwanza/Tanz.: Bilddokumentation von M.N. Filgis aus der zeit vom 22.7-10.9 1970 [Photo documentation by M.N. Filgis from the period 22.7-10.9 1970] (Starnberg: Institut für Tropenbau, 1970). BIB 241908, Georg Lippsmeier Collection, CCA. Gift of African Architecture Matters. For more on this photobook see, Gareth Hammond, “Expertise in the Comfort Zone,” CCA, 2017. ↩

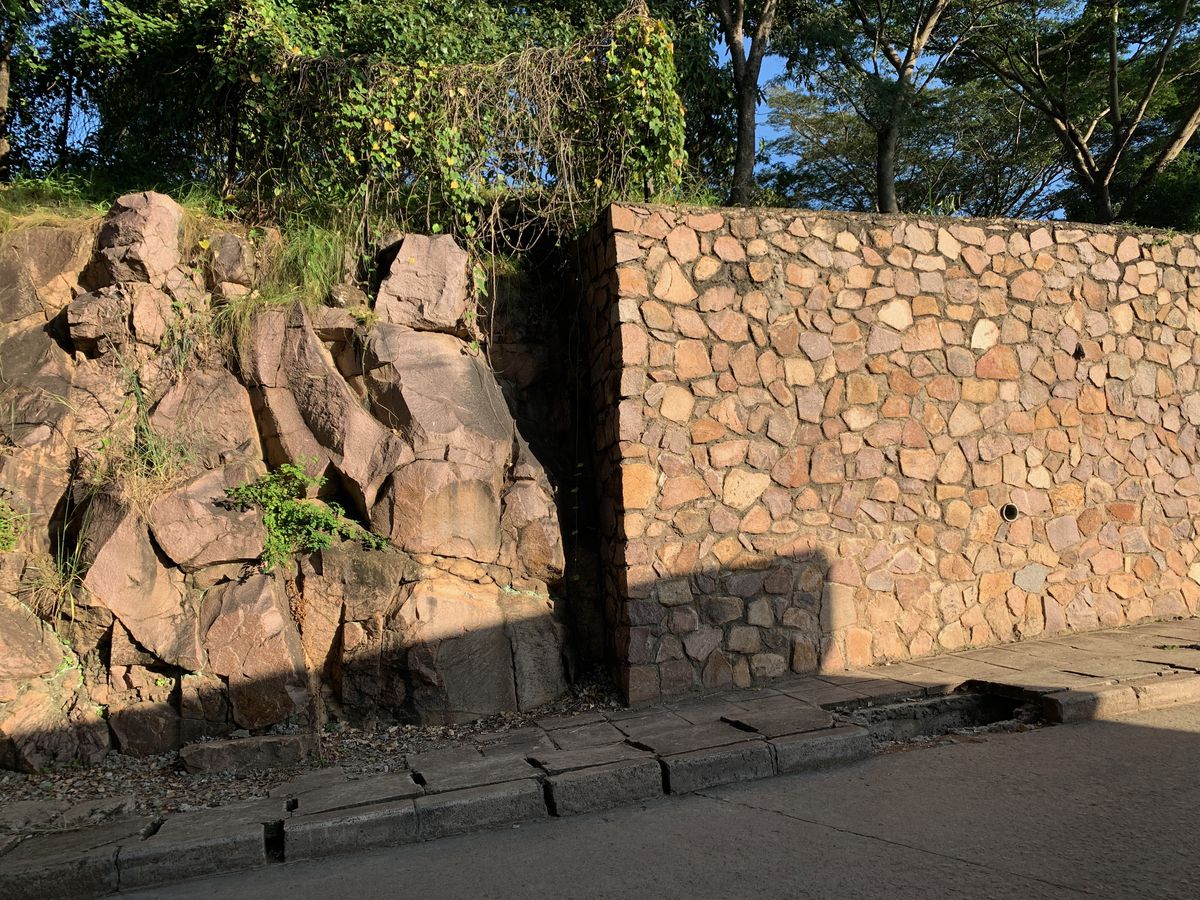

It remains unclear why Bugando Hill was selected as the site for this large hospital and who was responsible for the decision. As one of Lippsmeier’s long-time employees, the architect Hans Demeter, has pointed out, the rationale behind this particular location was not entirely clear to the architects either, but apparently “the Dutch charity insisted on it.”1 And yet the location does take advantage of environmental conditions: the site’s elevation allows the hospital to benefit from breezes coming off the lake and offers patients and staff views of the city and landscape from their rooms. Before the hospital was constructed Bugando Hill was topped with the same boulder formations that define much of the natural landscape around Lake Victoria, however these were destroyed to create a terrain suitable for construction. A slide in the Georg Lippsmeier Collection seems to document some of this violent eradication—in the words of Hans Demeter, “they had to blast the hill.” Slides of schematic design layouts for the overall plan of the hospital—probably cut-out paper arranged on prints of an aerial photograph taken of the site and then rephotographed—present the site as a tabula rasa, devoid of its previous distinguishing features. The complexity of the landscape has been expunged, replaced with a razed field to be occupied by the precise points, lines, and axes of Euclidean geometry.

-

Hans Demeter, interview with authors, 23 April 2019. ↩

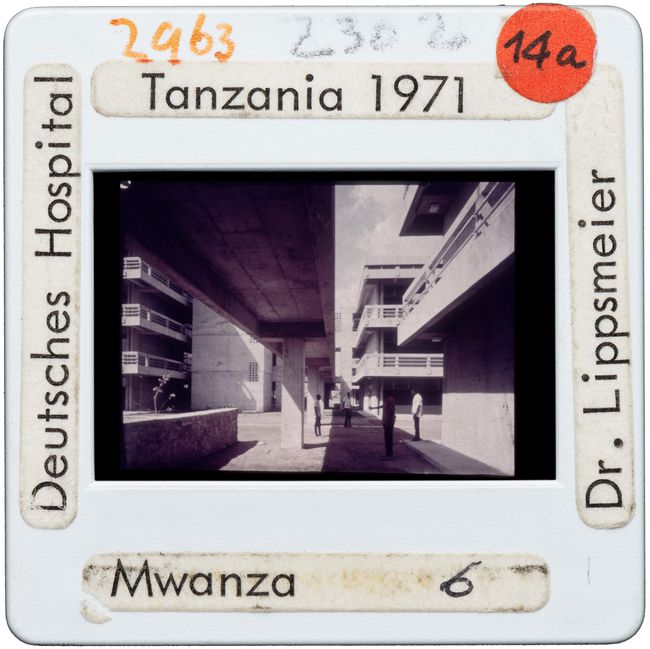

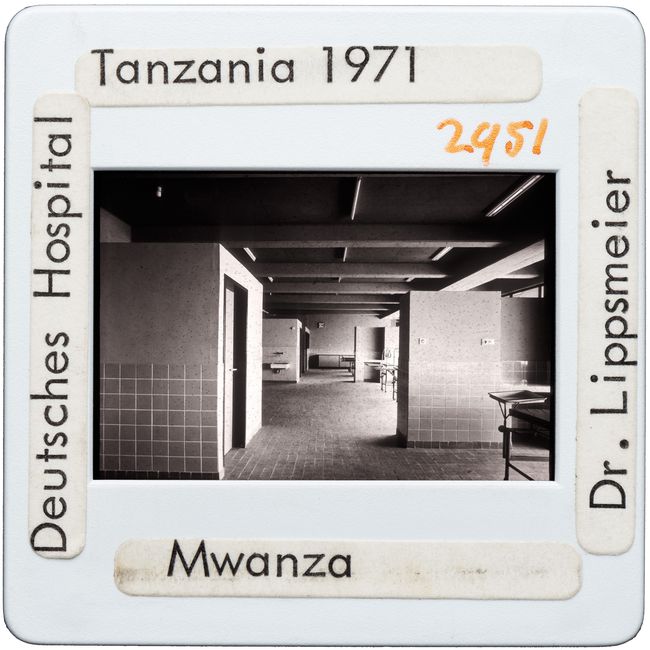

A form of neocolonial erasure is also present on a much smaller, everyday scale in how the slides in Georg Lippsmeier Collection are labelled, thus indicating how the architects, and perhaps others, perceived the project: sometimes the labels refer to the project as “Deutsches Hospital” [German Hospital], eliding the input of the Dutch and Tanzanian stakeholders. Today, however, there seems to be little or no memory of the German contribution, despite the plaque outside the registration office at the hospital’s entrance that reads, “The Mwanza Hospital. This hospital was formally opened by his excellency Julius K. Nyerere, the President of the United Republic of Tanzania, on the 3rd of December 1971. It was built through the generosity of people from West-Germany and Holland through the organisation of Catholic missionaries.” Rather than being considered a German project, many believe the hospital was “built by missionaries” or directly linked with the agency of Tanzanian government.1

-

Bugando Medical Centre staff, interviews with authors, 6–11 February 2021. ↩

Georg Lippsmeier, “Deutsches Hospital,” Mwanza, Tanzania, 1971. Slide. ARCH284647, Georg Lippsmeier Collection, CCA. Gift of African Architecture Matters. © Estate of George Lippsmeier

Soon after opening, the Tanzanian government nationalized the Bugando Medical Centre. In 1985 however, after the government realized it had limited capacity to efficiently run the hospital, it handed management back to the Catholic Church (Episcopal Conference of the Catholic Bishops of Tanzania), which has since operated the hospital in collaboration with the Tanzania Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. The facility is currently a referral hospital for northwestern Tanzania, serving eight of the country’s thirty-one regions and an estimated population of fifteen million. With an inpatient bed capacity of over 950, it is still one of the largest medical facilities in the country, embedded both in the Tanzanian healthcare system and in the urban landscape of Mwanza. Over the years, it has become an important teaching institution affiliated with the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences—thus fulfilling the initial plan, even if students or medical staff are not housed in the main building as envisioned by the architects. And as a tertiary centre, Bugando is also an important research facility with state-of-the-art cancer treatment services. Recently, the hospital has been fundraising to construct cancer wards, following the apparent lack of capacity to accommodate patients from the Great Lakes region.

Although undoubtedly a crucial part of Tanzania’s medical infrastructure, the hospital’s historic and socioeconomic significance to the region is defined by its elevated, monumental presence in the city, attracting visitors from all over the country whenever they are in Mwanza. Whether they are driven by mere curiosity, tourism, or a referral for medical services, the people persistently moving to and from the hospital throughout the day significantly boosts the surrounding economy. They increase the demand for transportation services, such as taxis and motorcycles; they are regular customers for businesses, including the coffin and grave marker merchants that flank the road that winds steeply up the hill; and they are frequent guests of the nearby restaurants and guesthouses. The area in the direct vicinity of the hospital has even become something of a health cluster, with a children’s hospital and a Hindu hospital across the road.

Although the massive structure remains an anomaly in Mwanza’s urban landscape, it has become a fulcrum of not only healthcare, but also social infrastructure. Despite all the ambiguities and asymmetries in its conception and construction, the Bugando Medical Centre appears to have evolved, over nearly half a century of constant use under Tanzanian governance, into an illustration of the “social infrastructure” that Georg Lippsmeier and his team promoted. According to them, such infrastructure included “all facilities that make a diverse community possible. It covers the areas of social needs, and societal and organizational requirements.”1 In this regard, the hospital functions in a fundamentally different way from the other architectural remnants of German colonialism, the Gunzert House and the citadel. Even though the hospital’s history might be linked to neocolonial practices, and even though the massiveness of its structure remains an anomaly in Mwanza’s urban landscape, it has become an organic part of the local urban ecosystem, no longer an isolated, erratic, or even foreign, body.

-

Peter Richter and Horst Strassburger, eds., Vorstudie zur Ermittlung von Planungsgrundlagen für die Soziale Infrastruktur in Entiwicklungsländern [Preliminary study to determine planning principles for social infrastructure in developing countries] (Starnberg: Institut für Tropenbau, 1978), 52. Georg Lippsmeier Collection, CCA. BIB 242086. Gift of African Architecture Matters. ↩

The authors would like to reiterate their gratitude to the staff of Bugando Medical Centre, particularly Prof. Dr. Makubi and Dr. Mwaipopo, and to thank Prof. Dr. Charles Mkony and Dr. Simon Mpyanga.

Rachel Lee and Monika Motylinska wrote this text, with Arnold Mkony, as part of their research for the Multidisciplinary Research Project Centring Africa: Postcolonial Perspectives on Architecture.