A way of being an architect

Sebastián Adamo and Marcelo Faiden revisit the recent architectural history of Buenos Aires

There is a way of being an architect that draws on desires and demands, superposed interests and a wide variety of urges projected towards architecture from environments that are quite distant from one another. The design methods and techniques developed by this model of professional find their maximum potential when facing ordinary situations. Its production becomes relevant when no one requests it. Almost always and almost anywhere. This way of being an architect is then associated with a large field of action. An extensive, ductile environment in which to deploy its agenda.

For better or for worse, the city of Buenos Aires favoured the development of this way of being an architect. A historically meagre program of competitions prevented the proliferation of architects focusing on public work. The exceptional materializations produced under this system of contracting have become just that: exceptions. Neither the city nor professional practices have been shaped by protected occasions for projects—that is, for buildings that are desired and produced independently of private interests.

Given this rather unstimulating description, it is worth noting that this same city enjoyed a fluid cultural exchange with the world. Ideas have travelled back and forth, through the skies and across the oceans, guarded by architects with a universal vocation, eager to participate in the debates that ran through each one who took part in the discipline. It’s possible that the architectural production of Buenos Aires responds to a great extent to the scarcity of institutions that promote it, and to an extreme vocation to practice it at all costs. The protagonists embarked on this approach realized that the characteristics of their environment would prevent them from accurately reproducing external models. And instead of offering resistance, they used their entire arsenal of contingencies to unleash a fresh iteration of the same design protocols, making a context run through by the laws of the market offer surprising versions of a disciplinary agenda that was tried out in other contexts. This group of architects will be responsible for expanding the elements involved in the project. For them, designing will also imply finding the right position within each economic cycle; will imply the careful construction of a new kind of client in keeping with his interests and, above all else, it will imply developing a keen sense of opportunity.

But to describe this way of being an architect more precisely, we may need to go a little deeper. If so far we have referred to one’s ability to combine an architectural agenda in a challenging context, to say the least; finally we enter the sphere of private obsessions and fantasies, placed at the service of one’s own idea of domesticity. The social and economic conditions of Buenos Aires were accompanied by a dense, compact fabric, built on relatively small plots that were easy to regenerate. This environment will shape a fertile territory in which to try out new models of collective housing. This will be was the chosen typology. The group of architects to which we now want to turn our attention decided to build their own homes surrounded by other people and other buildings. Dissolved in the landscape of a city that today weaves a century of history by stopping at each of these buildings. Transforming each case into an observatory to rediscover our territory. A place from which we separate ourselves from the ground to obtain distant views capable of running through time and renew the sense of our ambitions.

This group of architects will not need to build their homes in isolation from the world, enveloped in a stimulating natural landscape, to conceive a work with its own agenda. Nothing could be further from the carte blanche represented by the series of houses built and inhabited by the architects that almost all of us know. Here we are interested in those buildings where the real-estate market has imposed its conditions and the project has managed to weaken its conventions and evaluation criteria. This way of being an architect will go beyond the traditional scope of the project. It will manage a larger volume of variables and will take on many more responsibilities, stepping into an enviable freedom of action. The use, the location and the architectural resolution—the what, the where and the how—will become simultaneous design elements of the same hierarchy. Contrary to the increasing incorporation of new specializations in the field of construction, the architects of Buenos Aires will adopt an active resistance set on breaking down the path leading from the project to its future inhabitants. In this way, they will offer a reference model for building a practice capable of dissolving private obsessions with public needs. And not because a handful of the enlightened had cut this Gordian knot, but because this pragmatic attitude will be transferred from generation to generation, directly impacting contemporary practices. The resulting panorama will describe a century-long journey through the fabric of Buenos Aires. A tour of buildings built under the same conditions as their neighbours, but capable of reminding us that every occasion can give rise to a critical, propositive architecture. This constellation of cases will reveal a great diversity of approaches to collective housing, but all will need a model of architect capable of offering a new point of view. A position that challenges the rules of the game in order to experiment with a new way of seeing. This series of cases will show how each moment will require a deployment of creativity that will progressively outline a specific model of practice, with a profile that is both recognizable and relevant.

Alejandro Bustillo took advantage of the development of a rental building to include his studio on the ground floor and his private house at the top. The techniques of spatial organization used, typical of classicism, are subjected here to the constraints of a small, irregular plot located between party walls. The main salon of his studio (photo) repeats the compositional elements we find in the housing units, but proportionally increasing the scale of the spaces and the architectural elements. The large volume of interior air gives the furniture an organizational freedom that goes beyond classical canons.

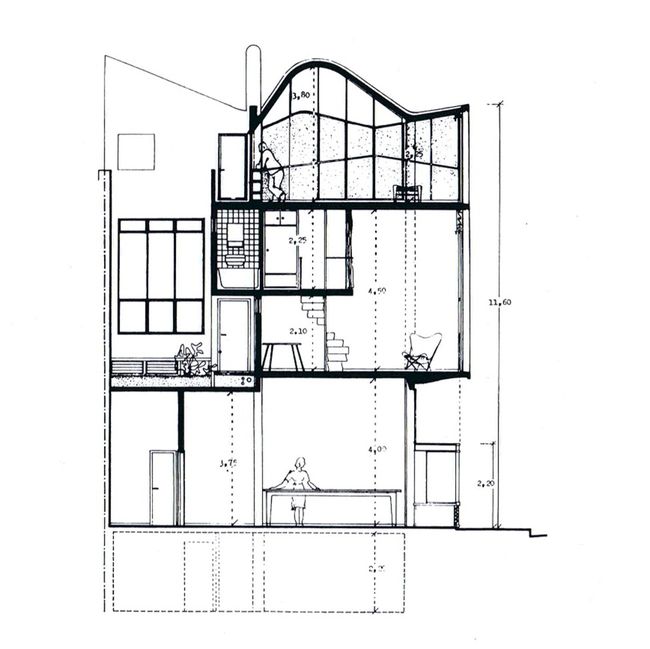

Antonio Bonet arrives in Buenos Aires recommended by Ferrari Hardoy and Kurchan, his former colleagues at Le Corbusier’s studio. His home was located at the top of his first American project, beneath a vaulted roof and beside a garden terrace that opened towards the city centre, in direct contact with the sky. The section presents the three layers of the project. At the opposite end to the vaulted units are the commercial premises, linked to the urban floor. Between the two, a series of small units, organized in double-height spaces, respond to the emerging demand for alternative housing options to the nuclear family home and new forms of work not yet addressed by the property market.

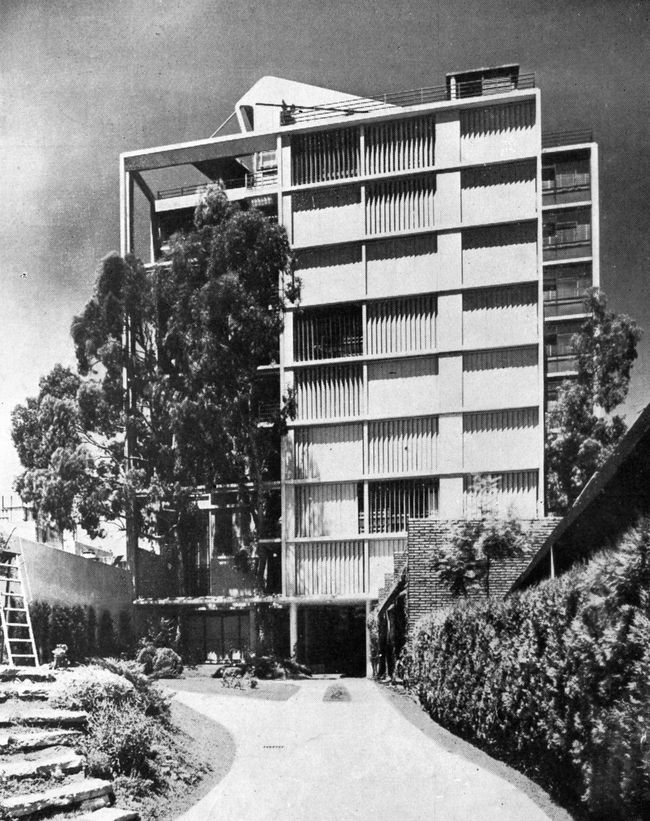

The modern block reached the fabric of Buenos Aires in the form of real-estate development, promoted in this case by the family of Jorge Ferrari Hardoy. It is a residential building, equipped with a restaurant, laundry and reading room located on the ground floor, beside an atypical front garden. The photograph not only describes the complex’s only façade, it also reveals the crystallization of a typological journey: while high-rise construction was born in North America, consolidating the street block fronts that later moved to Europe and attained their objectified version isolated in nature, the Los Eucaliptus building was the synthesis of both traditions. Its conception celebrated the arrival of the modern block in the urban fabric along with a fragment of picturesque nature, implanted with no mediation within the limits of a large front yard.

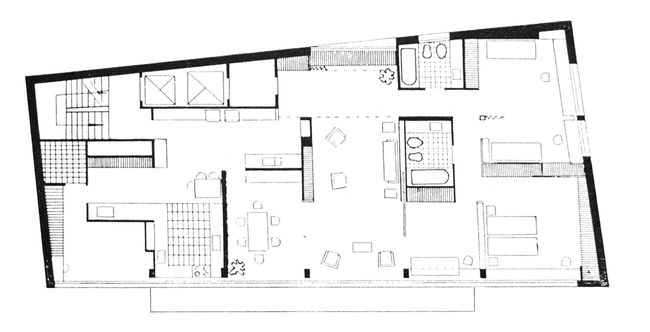

Mario Roberto Álvarez and Macedonio Oscar Ruiz built their own homes in a small tower while completing the construction of the General San Martín Theatre. An analysis of the typical floor plan of this building reveals that the two projects share the same layout technique: the service areas move towards the perimeter with the aim of “correcting” the geometry of the site and setting the stage for the main spaces, in connection with the glass façade. Within the new perimeter, the elements are articulated in a neoplastic way.

Rather like the analogue European collectives of the sixties, the University of Buenos Aires brought together this group of architects focused equally on academia and professional practice. Their successful performance in public competitions allowed them to invest the resources gained in each of the awards in the property market. The Coronel Díaz building was the undertaking in which they designed their first housing units. A vertical structure responds to the demands of each of its authors, generating a variety of units embedded in a structure of regular order. An outer facing of an industrialized framework painted “Yellow Submarine” colour contained the variations of each episode, transforming the tension between system and alteration into a plastic stimulus.