Lateral Gaze

Stefano Boeri on Gabriele Basilico, in conversation with Stefano Graziani and Bas Princen

This oral history was filmed by Jonas Spriestersbach in July 2022 at the Archivio Gabriele Basilico in Milan. It is part of the CCA project The Lives of Documents—Photography as Project, an open reflection on how past and contemporary image-making practices serve as critical tools to read our built environment and design today’s world.

- SG

- Sezioni del paesaggio italiano [Italy: Cross Sections of a Country] is probably one of the most interesting experiments between a photographer, Gabriele Basilico, and yourself, an architect and urban designer, on a shared topic of research. How did this project develop? What did it mean to you and what did it mean for Gabriele Basilico?

- SB

- I knew Gabriele and his work, but we began to speak more closely in Genoa, where I was teaching from 1993 to 2000. I invited Gabriele to develop a project on the port of Genoa—I was designing its master plan—and I immediately recognized how unique he was in terms of his precision and sensitivity.

At that time, I was working with Jean-Francois Chevrier, who was collaborating on Documenta X with Catherine David, when I started to explore the idea of an “eclectic atlas” of contemporary environments. An eclectic atlas incorporates a multiplicity of gazes to define a new balance between words, names, and concepts about place. I started considering photography as one of the main tools to deconstruct the hegemonic perspectival gaze normally used by architects and urbanists. I thought about how it could instead open new points of view on the contemporary city: on spatial changes, on the perspective of subjects that cross territories, and on the imaginaries of their inhabitants. I immediately understood that Gabriele could be one of the protagonists of this kind of lateral gaze, one that deconstructed a zenithal point of view to compose a montage of different perspectives on a territory—the eclectic aspect of an atlas.

Our collaboration took another step forward when Francesco Dal Co asked Gabriele, on behalf of Hans Hollein, to contribute to the 1998 Venice Biennale of Architecture, titled Sensing the Future: The Architect as Seismograph. The Italian pavilion curated by Dal Co focused on the work of a new generation of architects, with each architect represented by a distinctive sample of their buildings. Gabriele told me, “Francesco asked me to go to the places where these buildings are located to see what’s happening around them—would you please help me?” I suggested that he respond with a different proposal: an entirely new way to represent contemporary urban Italy focusing on what had changed over the last twenty years.

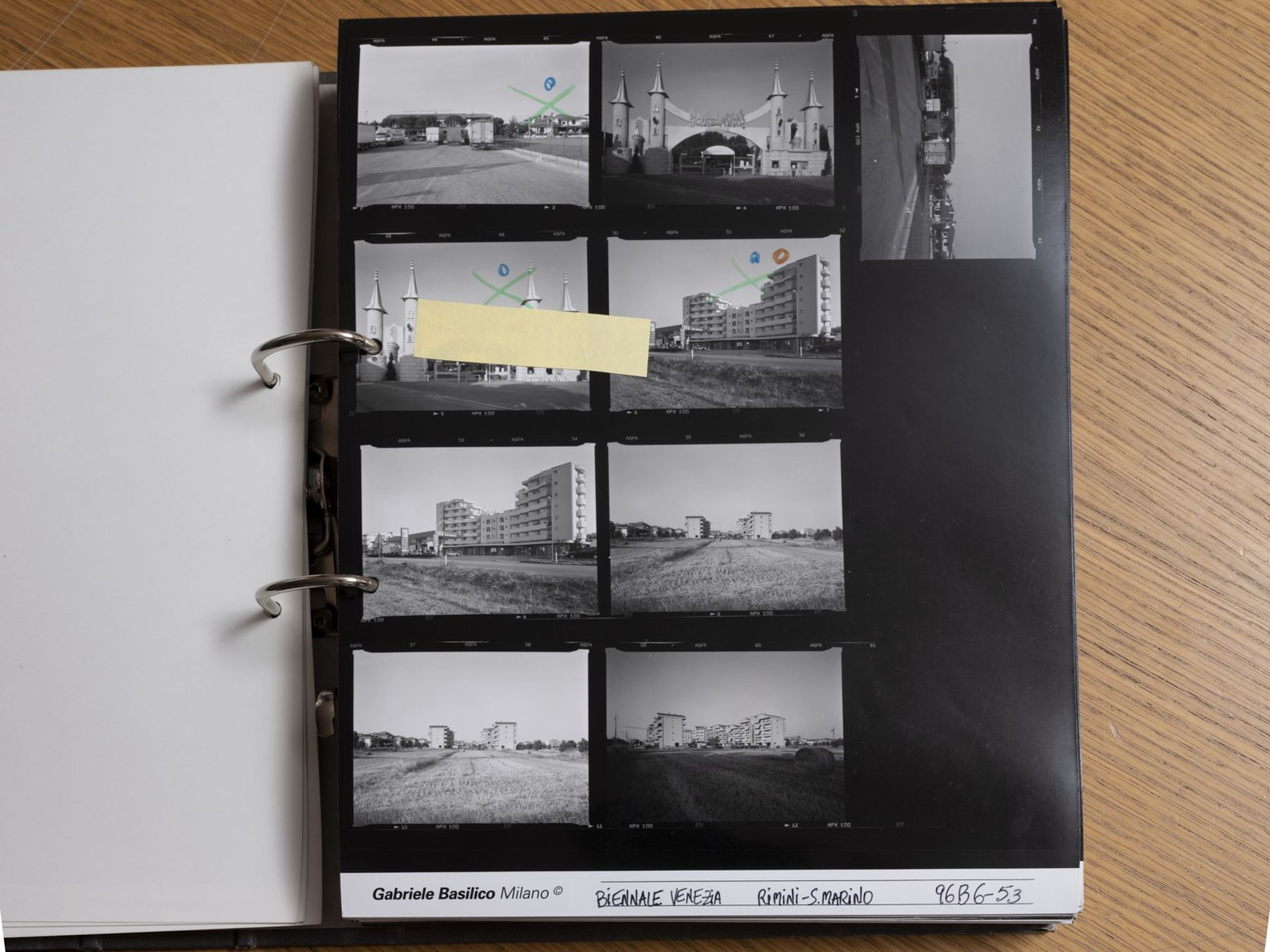

I had begun to investigate this approach with Arturo Lanzani and Edoardo Marini at the end of the 1980s. In 1992, we published a book called Il territorio che cambia, an eclectic atlas on the explosive changes and expansion of the Milanese metropolitan environment—a transformation produced by the seemingly chaotic sprawl of mediocre buildings across all major Italian cities. With Arturo, a geographer and researcher, and Edoardo, a photographer and researcher, I tried to decipher the rules behind that chaotic growth. I went deeper into this investigation with Gabriele. I told him, “Let’s explore six or seven samples of contemporary urban environments.” They had to be similar because it was important for the sample criteria to remain consistent, so I proposed to take what I called “biopsies” of various sections of the Italian territory. With John Palmesino, Gabriele and I began to work on this huge map, selecting 12 × 50-kilometre sections. We covered parts of the Italian territory with these rectangles, looking for peripheral environments near big cities that had been transformed by recent urbanization and featured interesting topographic features and one main road. At that point, we told Gabriele, “Let’s abandon the idea to see the primary works of these architects, and let’s go around them instead.” Then, I proposed that Gabriele try to capture everything that had been built in these territories in the previous fifteen to twenty years—that’s it. I knew how rigorous he was, so I sought to activate Gabriele’s unique gaze on those sections of the Italian territory.

Sezioni del paesaggio italiano (Italy: Cross Sections of a Country)

Life of the Project

1996

Over the course of two and a half months, Basilico and Boeri travelled along six urban corridors throughout Italy, photographing Sezioni del paesaggio italiano

1996

Exhibition: Sezioni del paesaggio italiano

Shown in the Italian pavilion at the 6th Venice Biennale of Architecture, Venice, Italy

15 September – 17 November 1996

1997

Publication: Sezioni del paesaggio italiano

Published by Art&, Udine, Italy

Texts by Stefano Boeri and Marco Folin, images by Gabriele Basilico

1997

Exhibition: Sezioni del paesaggio italiano

Organized at Photo & Co., Turin, Italy

18 September – 15 November 1997

1998

Publication: Italy: Cross Sections of a Country

Published by Scalo, Zurich, Switzerland

2017

Exhibition: Entropia y espacio urbano

Organized at the Museo ICO, Madrid, Spain

30 May – 10 September 2017

2018

Exhibition: Gabriele Basilico. La città e il territorio

Organized at the Museo Archeologico Regionale, Aosta, Italy

27 April – 23 September 2018

2020

Exhibition: Gabriele Basilico. Metropoli

Organized at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Rome, Italy

25 January – 2 June 2020

- BP

- How did you consider your contribution as a kind of research project?

- SB

- The project was always a form of research. I spent a lot of time writing a text that introduced the photographs and showed how indebted I was to Gabriele. He helped me confirm, enrich, and sometimes reveal weaknesses in my ideas about the urgent need to develop a new way of describing contemporary Italian environments. I was interested in seeing if it was possible to use our gazes as architects and as photographers to understand what was happening at that moment in Italian society and how it was reshaping the landscape.

Sezioni del paesaggio italiano was one of the first projects to describe the changes happening in Italy during the Berlusconi era, from the mid-1980s until twenty years ago. This was a period of dramatic transformation when a society composed of a few decision-makers was substituted by a multitude of authorities hoarding power and money invested in changes to private space. But they invested in mediocre objects, which did not encourage a collective ethic or individual taste. The model of the single-family home was so important at the time, as was the belief that your material condition could improve thanks to the mobility afforded by automobile access to all members of a household, each with their daily routine, each returning to and meeting in the family home and the main piazza at the end of the day.

At the time of our research, nobody in Italy cared to understand physical changes to the suburban territories as immense metaphors for what was happening in our society, and that was a big mistake. Urbanists still described Italy as a system of historical centres, without enlarging their gaze to the totality of urban settlements and without the awareness that territory is—and has always been—an imperfect metaphor for our society. Gabriele and I wanted to demonstrate how most Europeans inhabit a territory that is not only represented by the historical square or the Renaissance monument. We noticed how the further you go from the centre of Milan, of Naples, toward their suburban territories, the more you enter a territory composed of an incongruous and sometimes indecipherable montage of a few architectural typologies that repeat without a clear logic or composition, without a decipherable syntax.

- SG

- Sometimes Gabriele has been confused as this great traveller, which he was, but without being recognized for his ambitions to detect conditions of society and the built environment through photography. I’m curious about what you learned from each other in terms of your respective disciplines.

- SB

- I think that photographers often develop conceptual views independently from any intellectual suggestions provided by architects or urban designers. Gabriele was one of the first to use photography to change the vocabulary of architecture. He was always driven by the concepts of variation and repetition. While I considered Italian architecture in terms of a limited number of typologies—the mall, the single-family house, the block—Gabriele’s pictures reveal the infinite local interpretations of these types. Although the single-family house in Sicily and the single-family house in Brianza and the single-family house in Mestre have the same structure and follow the same architectural rules, they are quite different. Their variations reflect differences in local identity, family structures, and use.

The point of our collaboration was to see if photography could help us to decipher an urban phenomenon that we did not see and understand and to confirm our thoughts about the changing Italian territory. The concept of territory that Gabriele had in his mind often contrasted with the physical condition of environments he captured, a contrast that makes his pictures unique and rich and that I, joking with him, used to refer to as a kind of sadistic cruelty. I thought, “Gabriele, you are a sadist,” because he completely accepted the conditions that he saw and photographed in all their mediocrity; nothing of interest was under construction at that moment in Italian architecture. Basically, they were all bad buildings. Gabriele was able to respect this diffuse mediocrity and granted these buildings dignity through his photographs. He used the same approach to photograph the most mediocre and uninteresting single-family home in Brianza as he did to photograph an Álvaro Siza masterpiece, or the Basilica of Sant’Ambrogio. He always gave dignity to the object of his gaze by revealing, rather than hiding, its mediocrity. There’s a truth to mediocrity.