Postcards on the Move

Armin Linke on global infrastructure, the Anthropocene, and playing games with the public

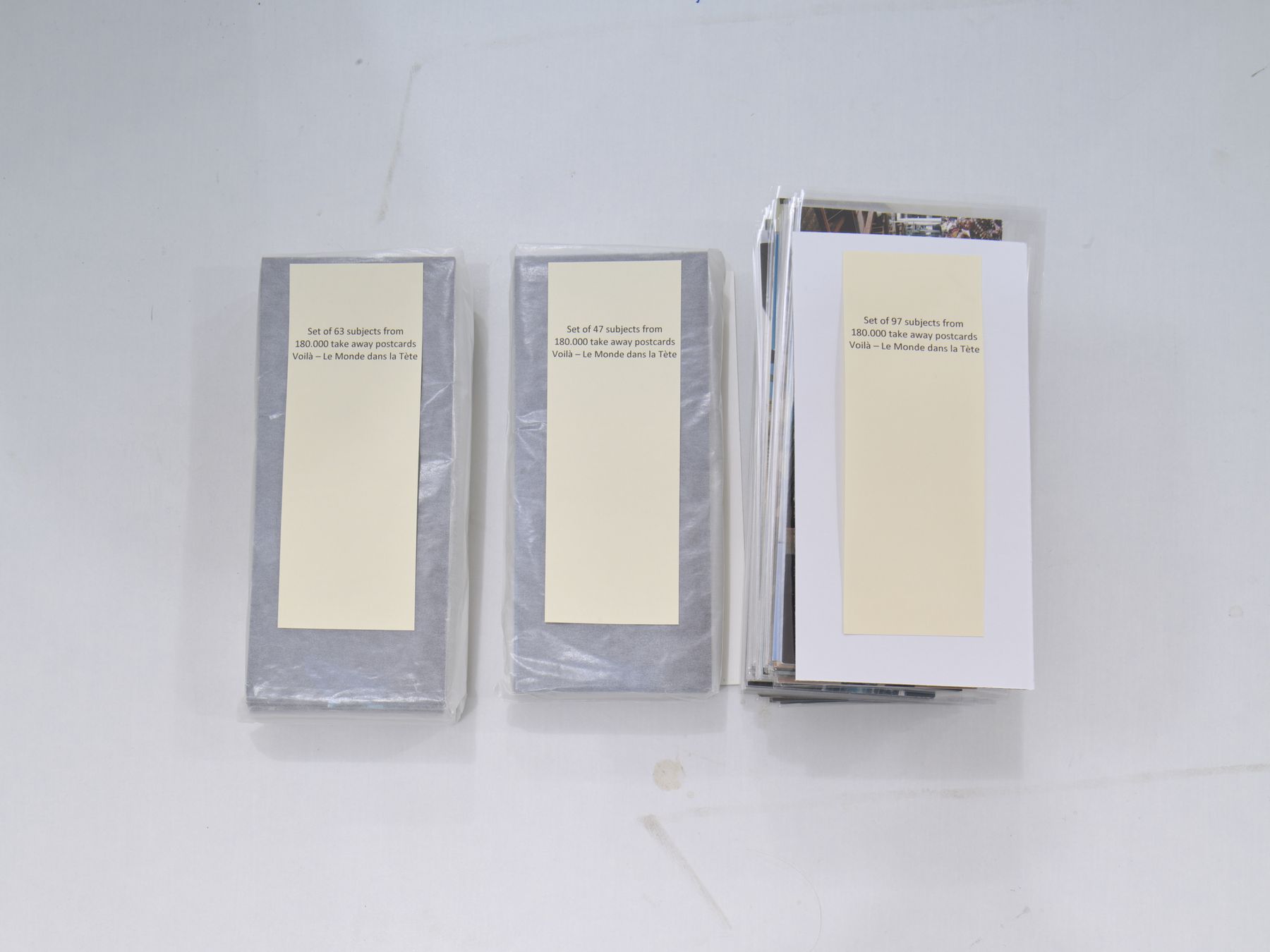

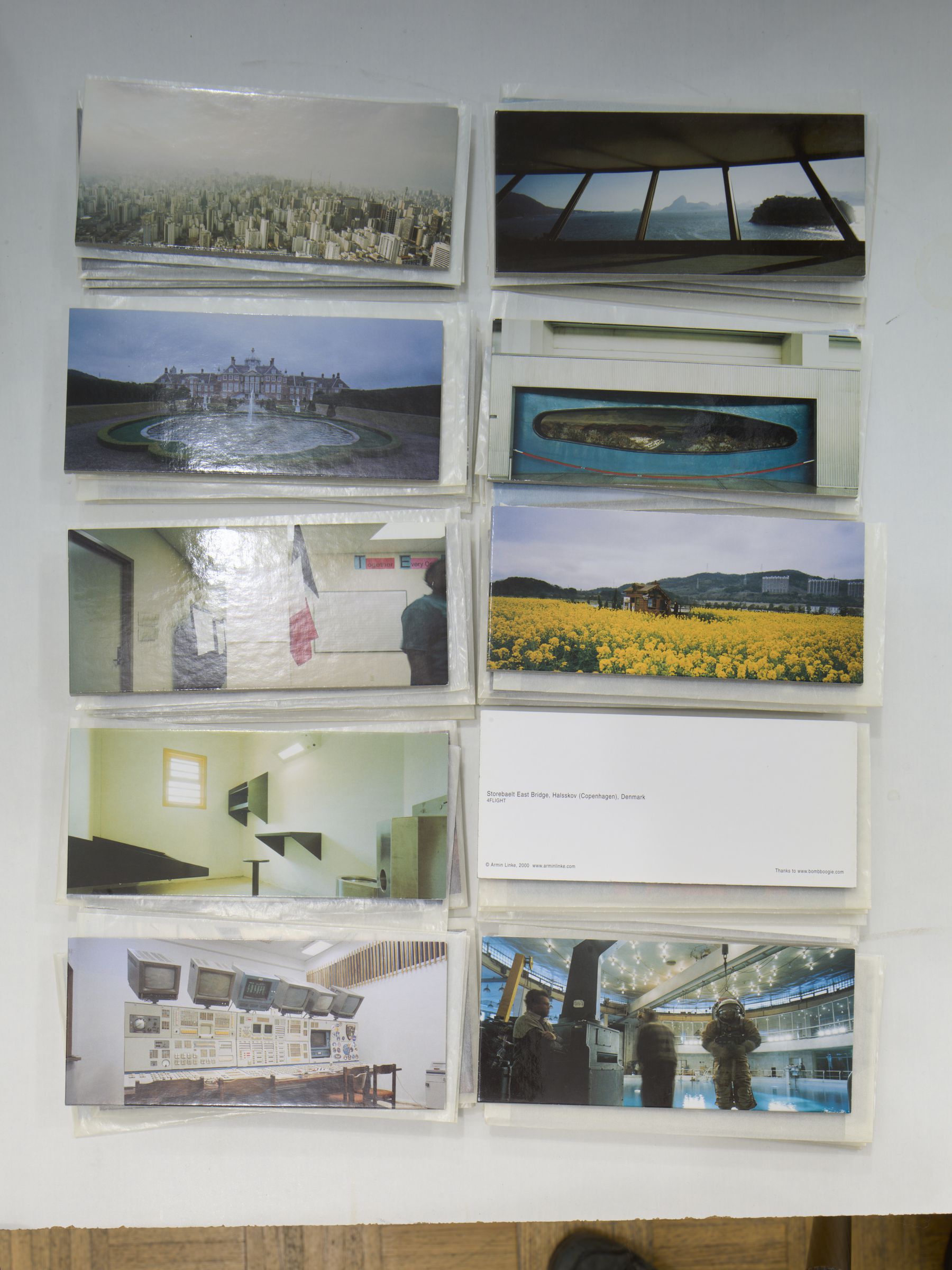

This visual essay is part of a series highlighting the commissions and conversations generated by The Lives of Documents—Photography as Project exhibition. Curators Stefano Graziani and Bas Princen commissioned photographer Armin Linke to reprint his suite of postcards from 4Flight, which viewers are encouraged to handle and take with them. Some are reproduced here alongside his reflections on global infrastructure and the Anthropocene, postcard photography, and playing with viewers’ expectations of photography and its display.

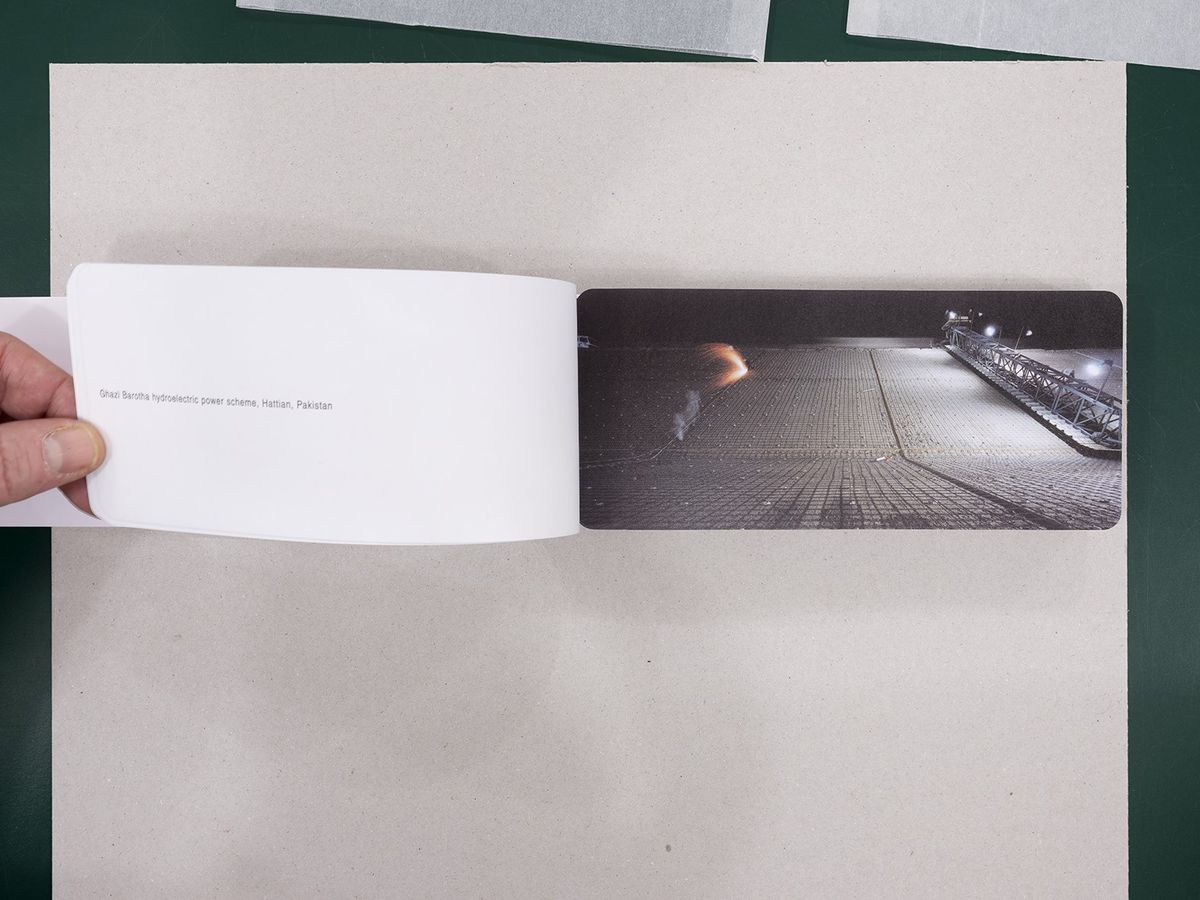

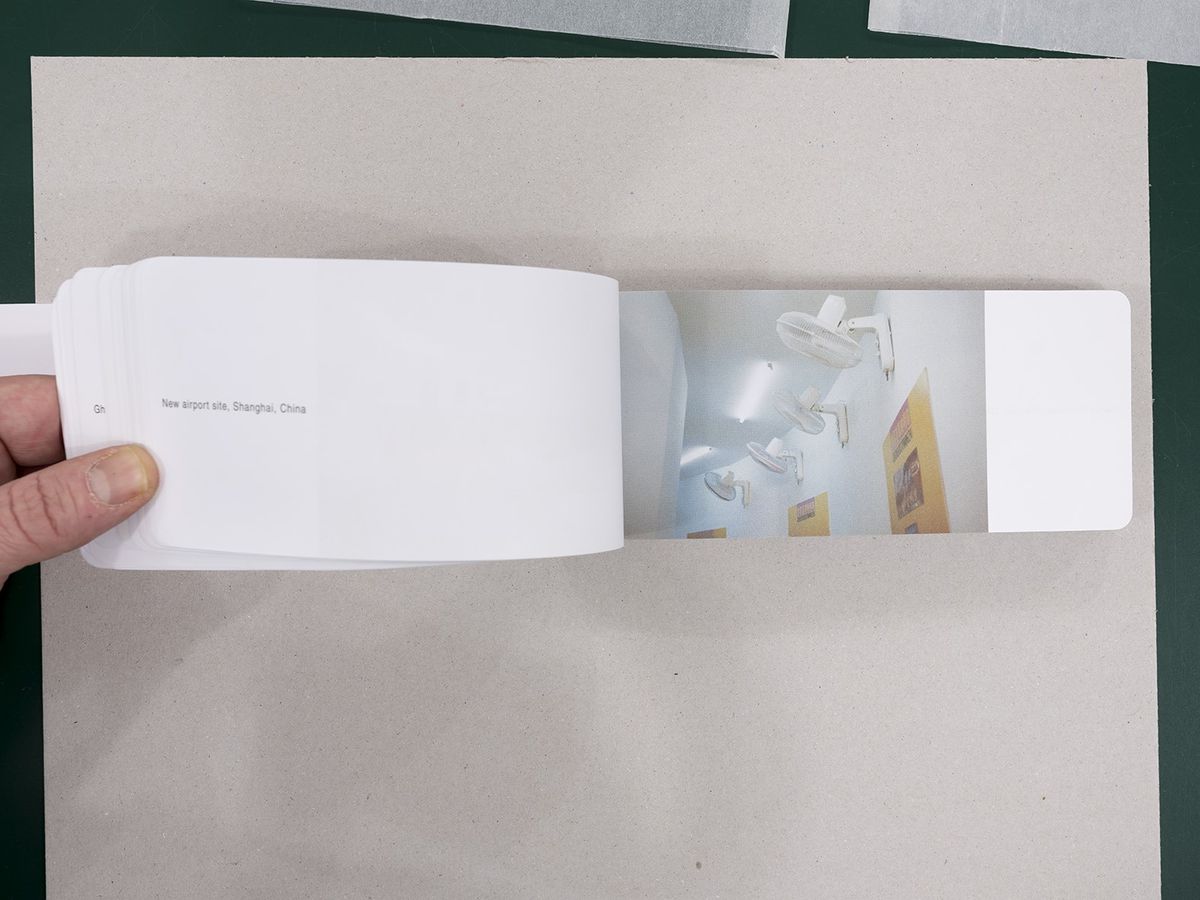

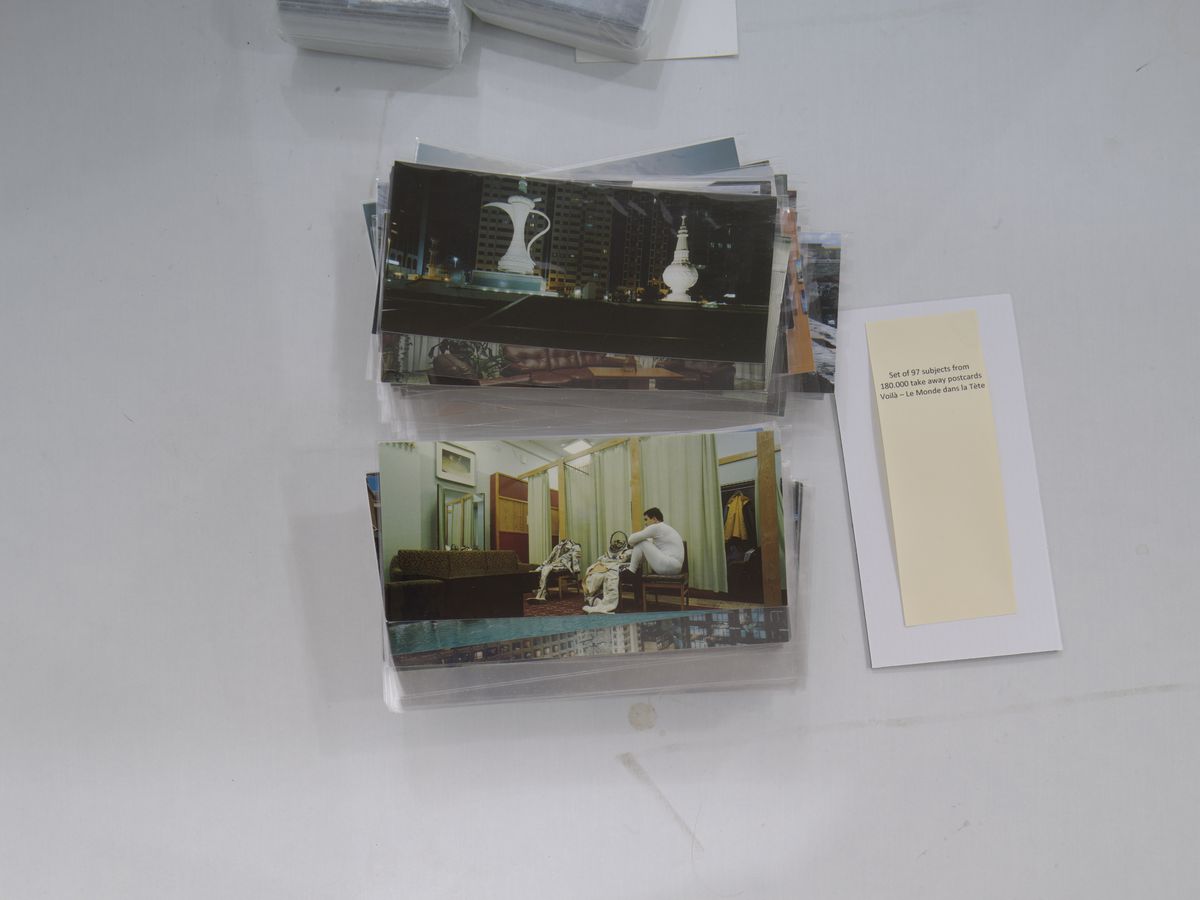

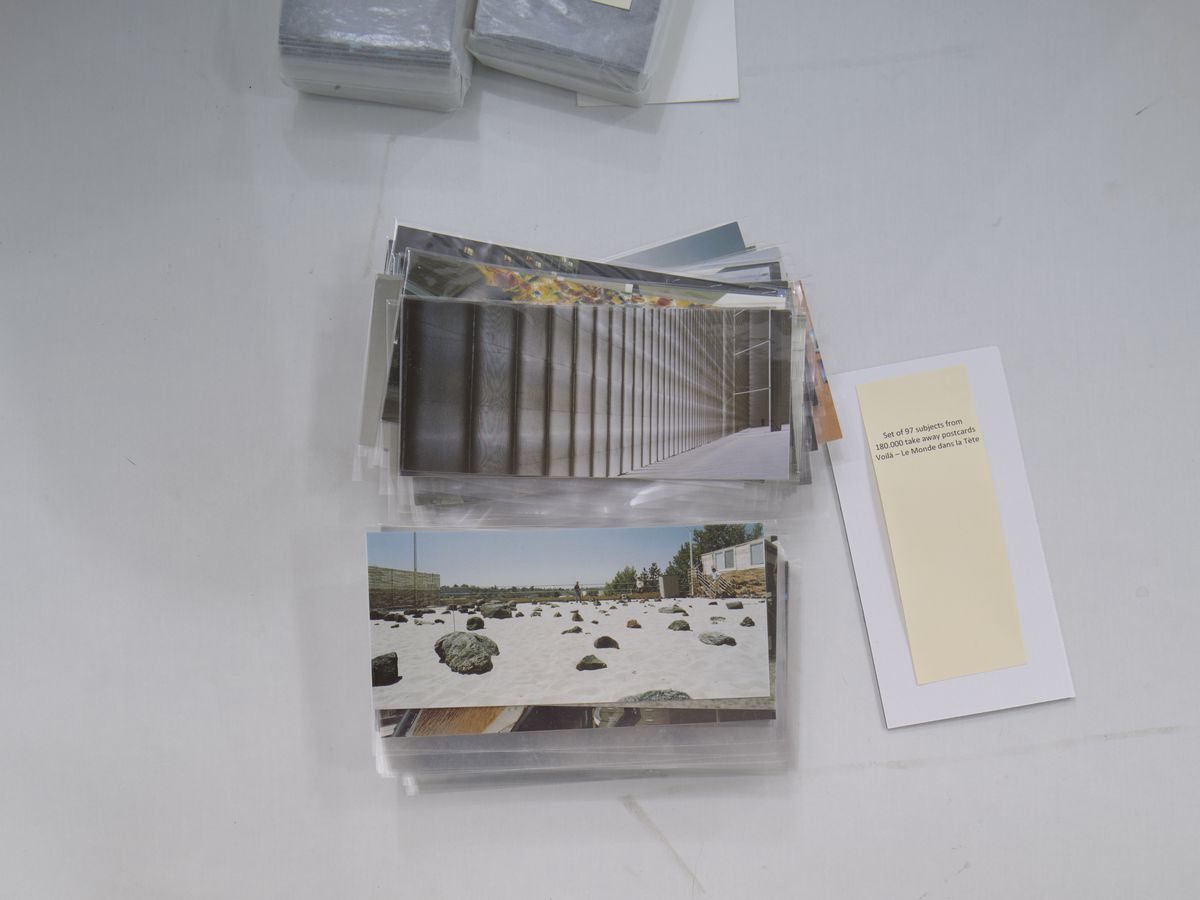

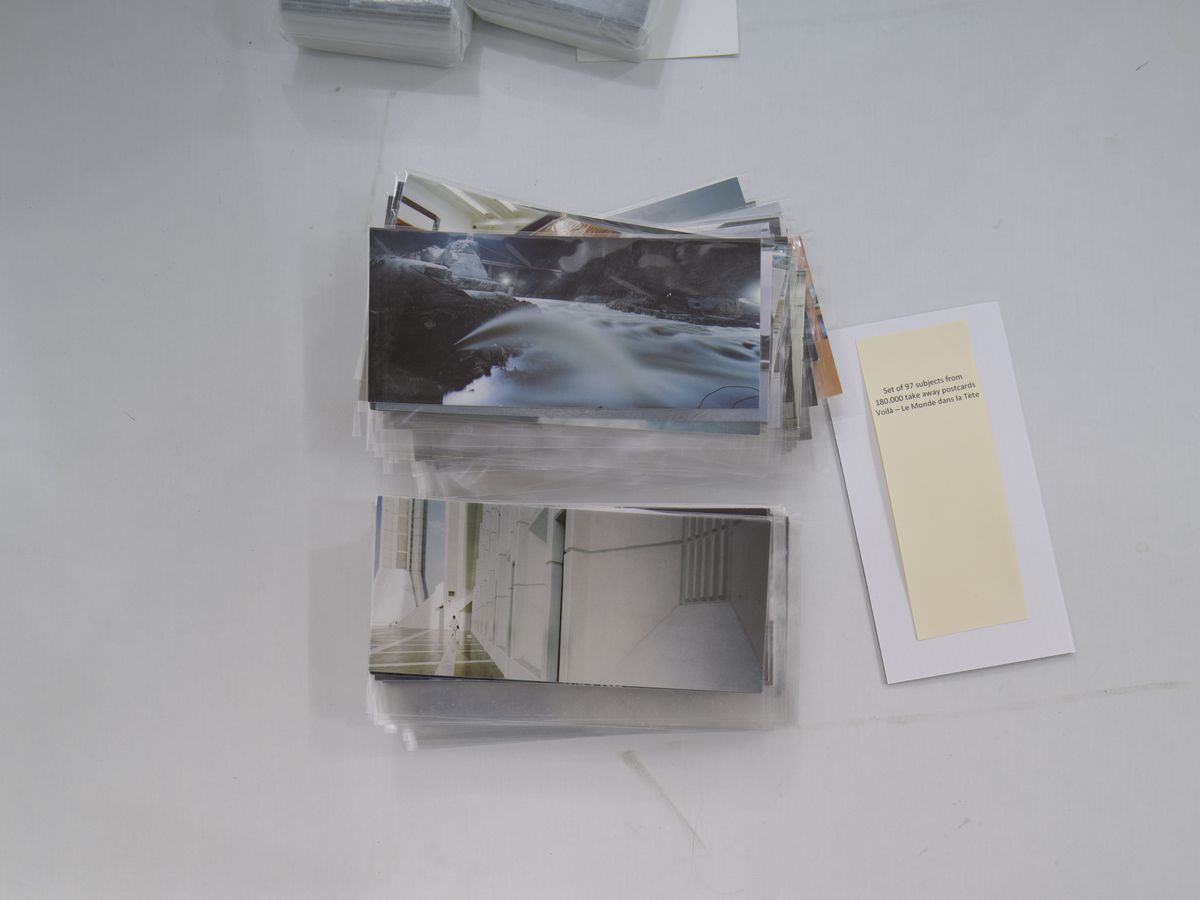

Many of my projects begin intuitively. For 4FLIGHT, I was interested in large infrastructural projects that deployed extreme interventions in the landscape through the lens of globalization, such as the Congo-Nile projects or the Three Gorges Dam. I would photograph the structures, as well as the workers’ fishing in the dam, at karaoke clubs, and their acccommodations. I wanted to look at architecture from an anthropological point of view, rather than at architects as authors, to learn about all the facets of the construction of such infrastructures, including their social and economic aspects. How do labourers build these structures? Why are they built? How are they financed, and what geopolitical issues does their construction produce? We have examples of technologically sophisticated infrastructure demanding large-scale displacement of people. Out of an interest in urbanism, I also photographed Kumbh dMela, a Hindu festival in India, during which a town of six hundred thousand inhabitants swells to accommodate forty million visitors, yet the local infrastructure functions without much technology, demonstrating that a low-tech approach to social and infrastructural management can work well.

The postcards and a related book were presented in 2000. All the pictures were taken after the fall of the Berlin Wall, at the time of surging capitalistic development, the acceleration and transformation of globalizing processes through large infrastructure projects, and massive social change. It became significantly more difficult to photograph after 9/11, not least of all because of how travel was impacted, but because the event introduced a new paranoia in society.

I conceive my photography in terms of its longevity; my pictures aren’t meant to comment on one-off events. Many of the images taken for 4FLIGHT were used recently in projects on the Anthropocene, and are, unfortunately, still very topical twenty-five years later. They are concerned with everything that happens around a photo and not only the subject it represents. In making 4FLIGHT, I thought of a laboratory connecting different places that seem to be distinct but participate in a general scheme to impose global infrastructural projects on societies. Of course, at the time, scientists hadn’t had yet proposed the idea of the Anthropocene, though I was intuitively working on it without a defined conceptual framework. The images in the project are connected because they reveal the human obsession to control landscapes and natural elements. They reveal how places that are distant in space and time are part of interconnected technological and cultural histories.

I’m not sure whether I’ve critiqued globalization enough, or have perhaps ended up celebrating it through representation. To me, this form of Modernist globalization has always been grotesque. There is always a promise of the future somehow embedded in the architecture of these projects or places I photographed. I hope I was able to bring in some irony, to show these were already utopias lost. Even as I was photographing, I was thinking, this is a lost cause. A dam is absurd when it’s oversized. There is something tragic and grotesque about its scale. Speaking with the engineers and architects who might have had the good intention to produce energy without fossil fuels, you’re asked to imagine this technological utopia, a sort of a Sisyphean undertaking. I’m interested in the concept of failure already embedded within these grandiose projects during construction; they promise a more efficient future but are destined to become ruins, given their short lifespans.

I’m interested in all genres of photography, in playing with their codes and different channels for their distribution. I often purposely use the “wrong” distribution channel or a channel in which you would not expect to see a particular genre of images. This creates a Brechtian moment, in a sense, as you are not only rethinking what you see in this image but also illuminating the entire production industry behind it. Sometimes I show an image taken for a fashion magazine in an exhibition with a completely different focus. I photographed garment production sites as a statement on logistics operations, globalization, and labour conditions.

My approach was also influenced by the exhibition Cities on the Move, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Hou Hanru in 1997. The exhibition was also like an urban laboratory, as the curators used unexpected juxtapositions to create “urban villages” in the exhibition space. As if in a city, you needed to find your way through the exhibition; the public could not be passive and needed to interact with the space and each other to find connecting threads. The ironic touch Obrist and Hou brought to the display prompted a sort of a game with the public, activating a public dialogue in a way that I found inspiring for my work.

Postcard photography operates in cliches, creating and disseminating visual typologies. A postcard flattens how a place is represented. I’m playing with the genre and inserting tension into its mode of representation by framing images with more of an anthropological or social charge. Printed on postcards and bound into the 4FLIGHT book, my images of infrastructure are presented like a movie location scout book. But the postcards are also geopolitical objects.