Coen Beeker’s Approach to Participation in Ouagadougou

Text by Philippe Genois-Lefrançois

Upon opening the boxes of the African Architecture Matter Collections at the CCA, researchers may immerse themselves in a multitude of documents pertaining to the work carried out by Dutch urban planner Coen Beeker across Africa, particularly in Burkina Faso. These documents include various studies and reports conceived by Burkinese administrative authorities on a number of urban projects initiated by Beeker; communiqués on the smooth running of field operations; numerous hand-drawn or printed maps produced by non-governmental firms or local authorities; dated aerial photographs and anonymous photographic prints; several contracts; and finally, a small sampling of books from Beeker’s personal library.

Although Beeker had participated in international cooperation programs focused on spontaneous settlements in Ethiopia, Sudan, and Tunisia, the urban planner had his most significant professional experience in Ouagadougou, in the late 1970s. This is where he developed the Méthode d’Aménagement Progressif (MAP),1 a progressive approach to redeveloping spontaneous settlements based on community participation, which had a significant impact on the Burkinese capital until the 1990s.

-

The MAP aimed at improving living conditions by granting residents a regulatory land title. At the time, land tenure insecurity was considered the main obstacle to improving housing conditions. Beeker proposed leaving households in place and restructuring the road network by modifying the existing physical and social fabric as little as possible. After consulting with residents, a development plan demarcating private and public spaces was established, and parcels of land were allocated. Residents were required to develop their own plot within a fixed period of time. The second stage, the provision of utilities and infrastructure, was then entrusted to the State. ↩

Beeker’s professional involvement in the Global South1 was grounded in a participatory approach,2 notably in the context of the subdivision program for spontaneous settlements in Ouagadougou. Beeker’s goal was to democratize urban living, through a process of advance consultation with residents who would be directly affected by this development, giving them a voice in the conceptualization and planning process. Beneficiaries were also invited to participate in the implementation of the subdivision program by developing their own private plots. The idea of self-development stemmed from a change, in the mid-1970s, in the discourse within major international development institutions, such as the World Bank and Habitat, which identified land insecurity as the primary obstacle to improving housing conditions.3

Coen Beeker’s MAP and his approach to spontaneous settlements in urban areas were part of a trend toward participatory urban planning, which first began to be theorized and standardized in the mid-1960s. Beeker’s archives demonstrate how the concept of public participation was articulated in Ouagadougou’s urban redevelopment project, at a time when Thomas Sankara’s Conseil National de la Révolution (National Revolutionary Council, CNR) was coming into power, in August 1983. The Sankarist regime seemed to signal a break with previous approaches to urban renewal in Burkina Faso, and coincided with Beeker’s growing involvement in the region.4

Read more

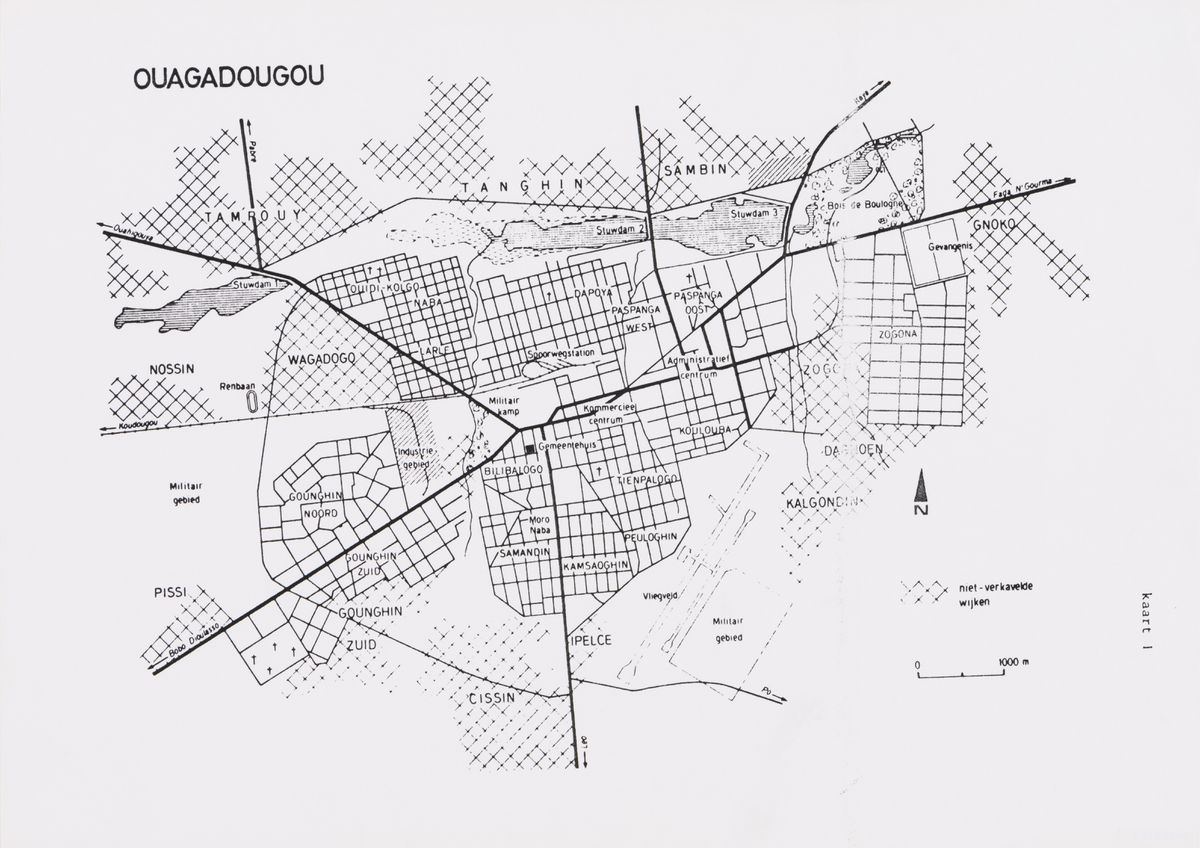

Throughout its history, the development of Burkina Faso’s capital was closely linked to the political context of the country. During its colonial period, from 1919 until independence, only Ouagadougou’s central districts, where mostly French officials lived, were subdivided into serviced lots. Following the country’s independence in 1960, the rest of Ouagadougou’s development was characterized by a laissez-faire attitude, and subdivision was only carried out intermittently following the interests of traditional elites who were on good terms with acting political authorities. The beginning of the 1980s was a politically unstable period in Burkina Faso, marked by multiple coups and culminating, in 1983, with the rise to power of Thomas Sankara and the CNR. At the time, there was no long-term vision giving Ouagadougou’s urban development, and some 30,000 ad hoc plots were the only instruments for urban planning across the capital region.5 The Coen Beeker Archive contains very little documentation of the period before the mid-1970s, except for a map of the capital from 1968 that, incidentally, does not indicate areas where spontaneous settlements had already been established.

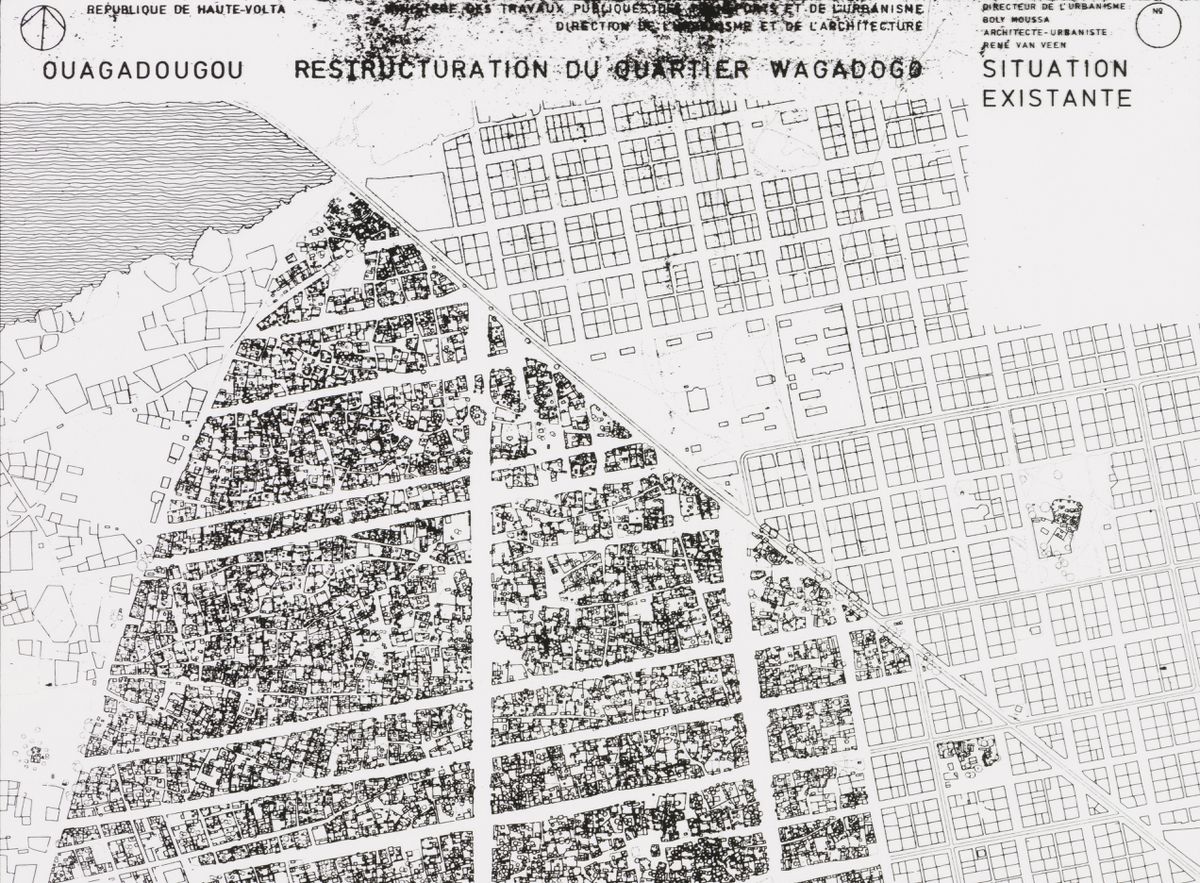

Coen Beeker first became involved with Ouagadougou in 1978 as part of a bilateral cooperation program between the Netherlands and Burkina Faso. Here, Beeker and his team worked on an innovative method of restructuring spontaneous settlements and politically rehabilitating the population into this “legal”6 city through subdivision and the provision of land security. In the spontaneous settlement of Wagadogo, in Ouagadougou, Beeker’s team implemented a pilot project initiated by the University of Amsterdam and funded by the Dutch government in The Hague, which promoted a comprehensive, long-term vision for Ouagadougou’s territorial development.

-

The Global South refers to regions also known as Third World or developing countries. ↩

-

Antoni Folkers and Iga Perzyna, The Beeker method: planning and working on the redevelopment of the African City: retrospective glances into the future (Leiden: Afrika-Studiecentrum, 2017). ↩

-

Annick Osmont, La Banque mondiale et les villes : du développement à l’ajustement (Paris: Éditions Karthala, 1995). ↩

-

Military Captain Thomas Sankara, leader of the Conseil National de la Révolution, took power in Upper Volta on August 4, 1983, and renamed the country Burkina Faso, Le pays des hommes intègres (the land of honest men). He established a voluntarist regime that combined Marxist-Leninist thought with African nationalism. Sankara was assassinated on October 15, 1987, during a coup that brought to power his former comrade, Blaise Compaore, a representative of the Popular Front. ↩

-

Kaboré, 2009. ↩

-

With independence, restrictions on rural-urban migration fell, and urban areas began to grow at nearly exponential rates. As of 1961, there were 1,717 hectares of unallotted areas compared with 1,552 hectares for the lotted area of Ouagadougou, which then had a total population of 60,000. Unallotted areas, also considered to be spontaneous settlements, soon expanded due to the dual phenomenon of organic growth and rural exodus, fuelled in particular by the great drought of 1973-1974. Ouagadougou’s population grew from 250,000 in 1978, to 440,000 in 1984. The urban region’s greatest demographic growth was found in the city’s unstructured peripheral areas. In 1983, 70 percent of the city’s area was occupied by spontaneous settlements, which were home to 60 percent of the population. Data from Abdelhafid Hammouche, “Le désenclavement des quartiers périphériques de Ouagadougou : un projet pour la maîtrise de l’extension urbaine” (M.A. thesis, Université Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV), 2008). ↩

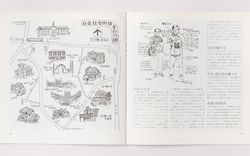

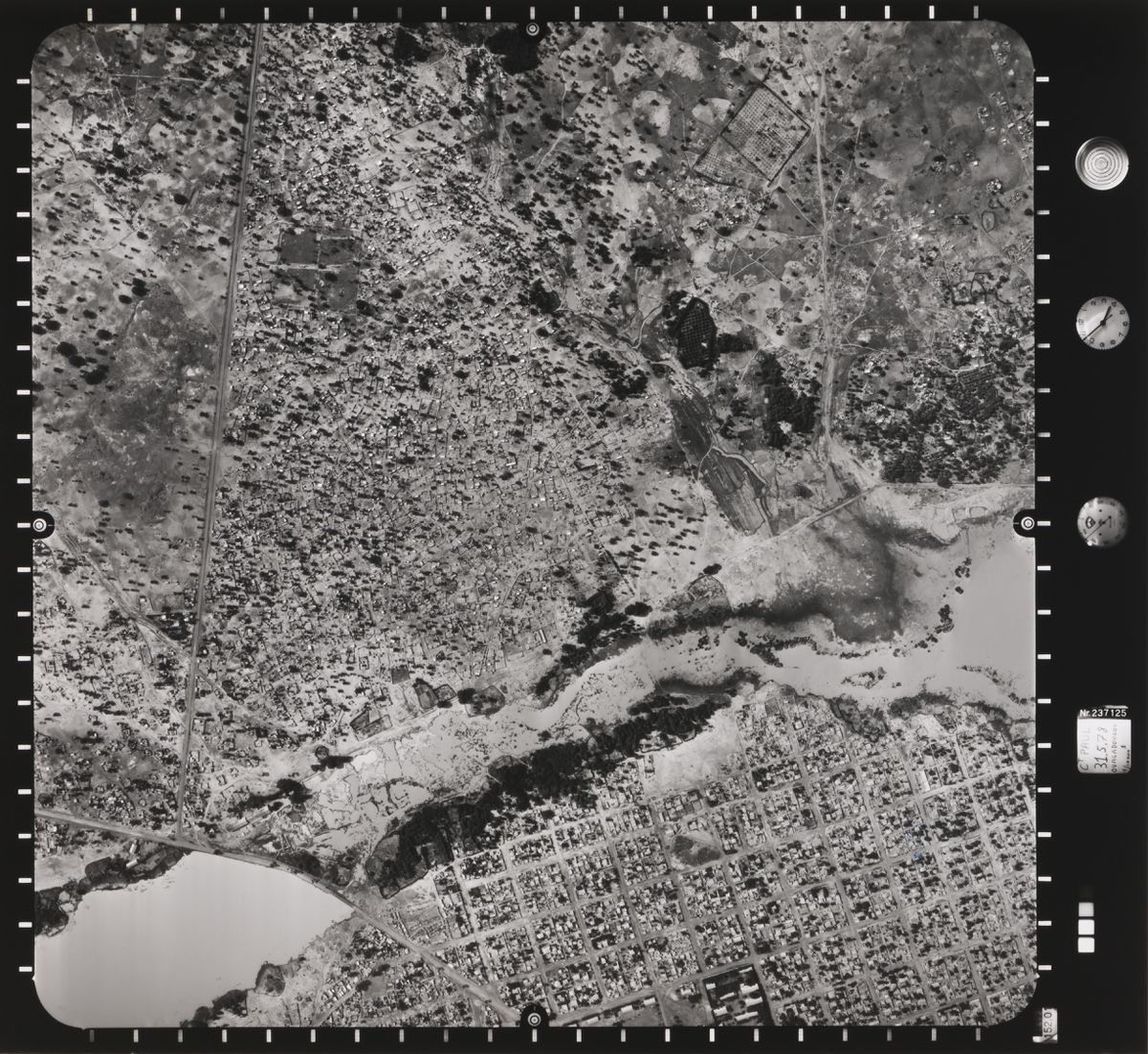

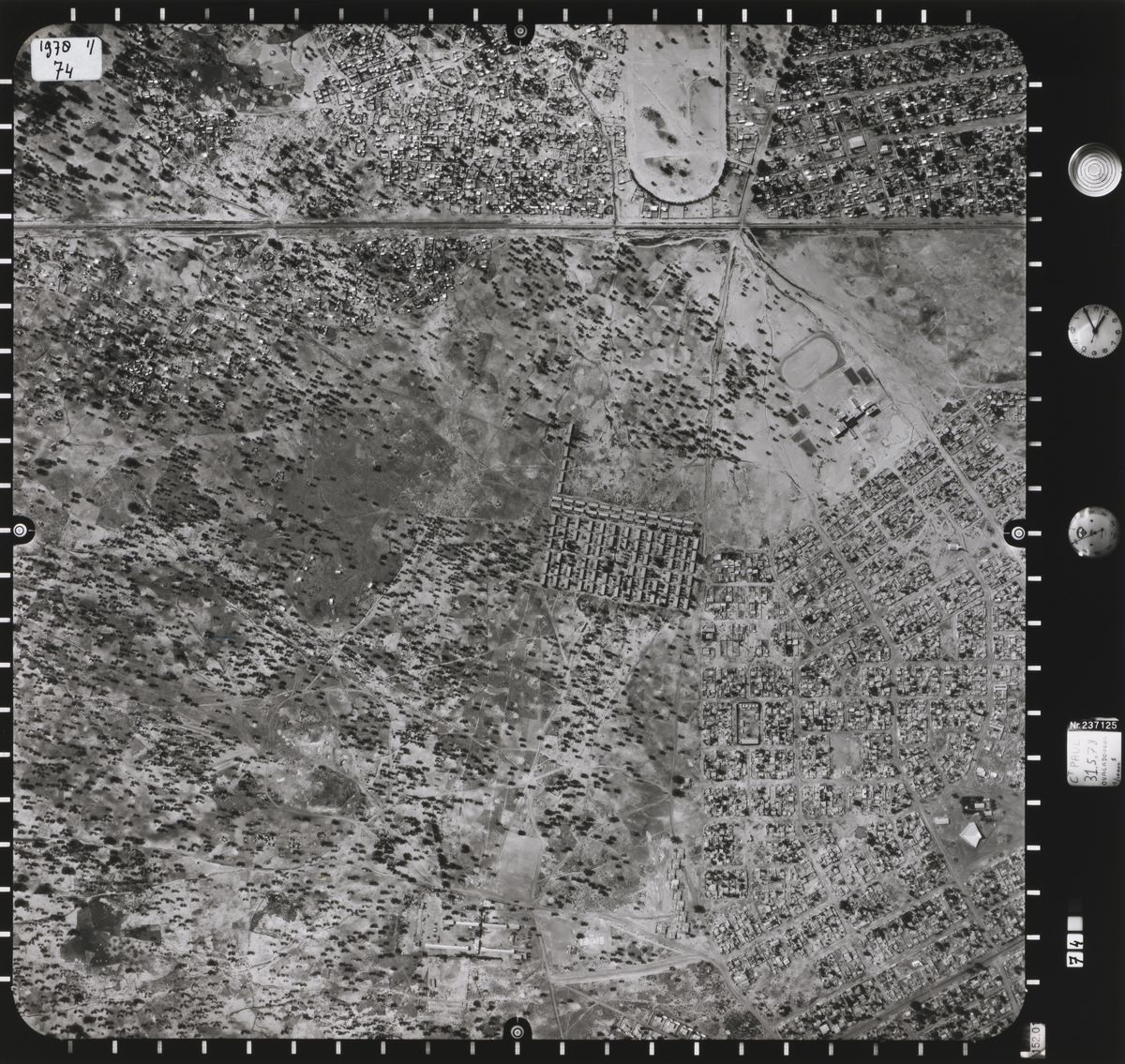

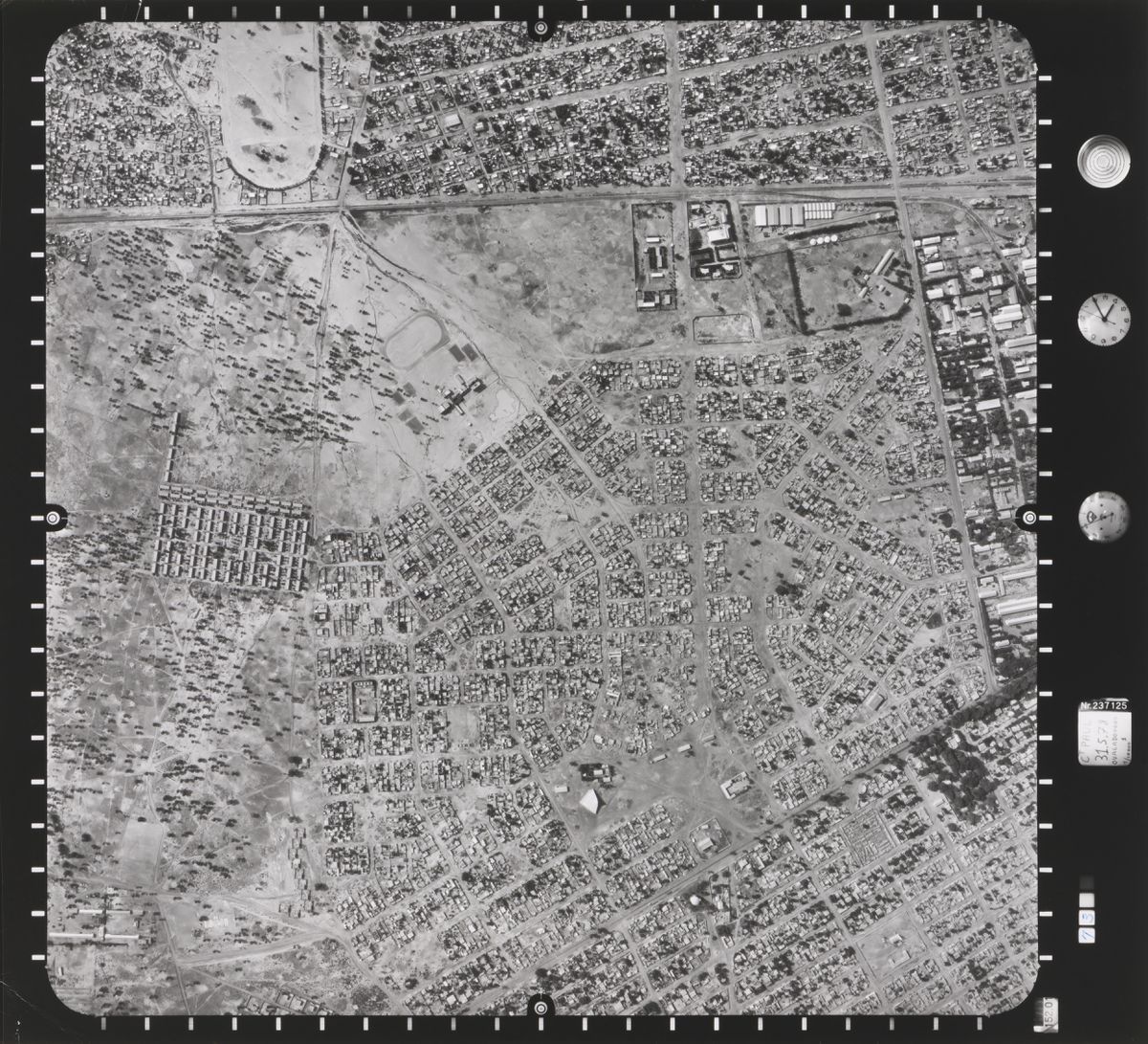

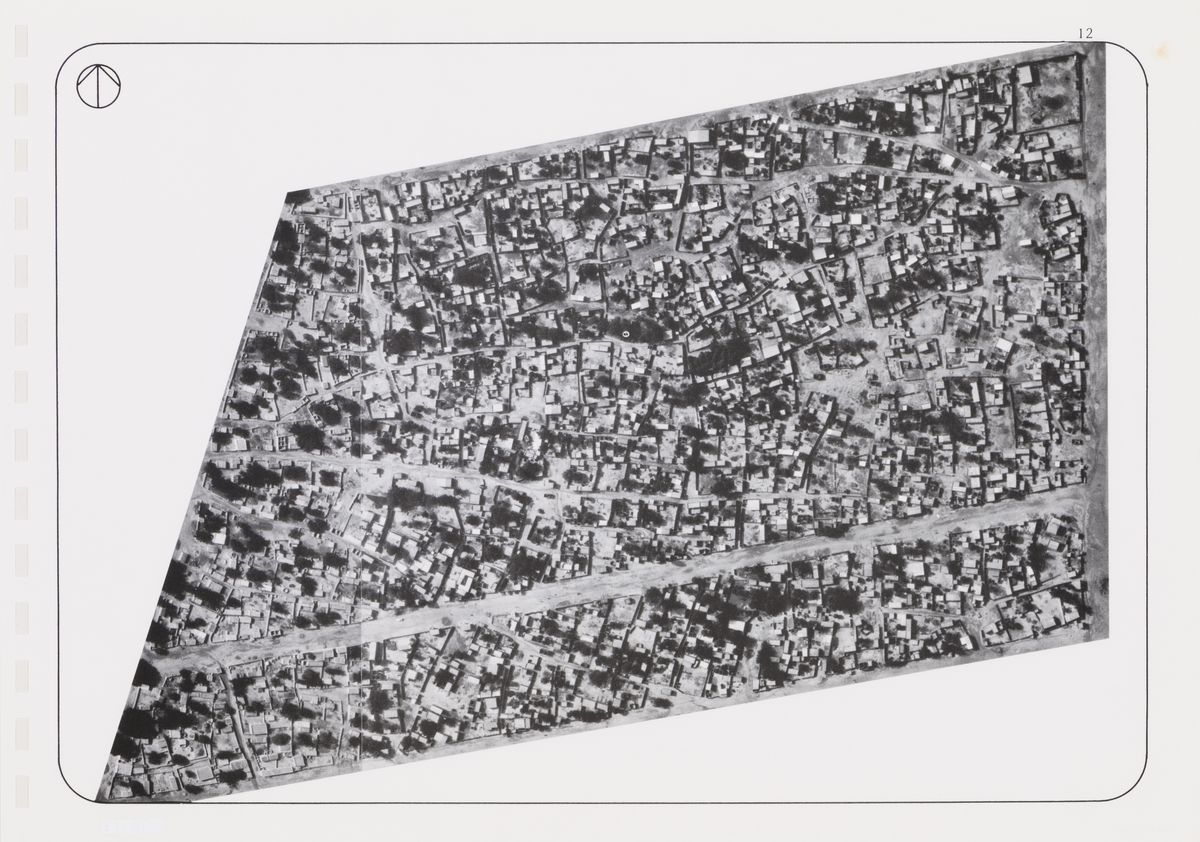

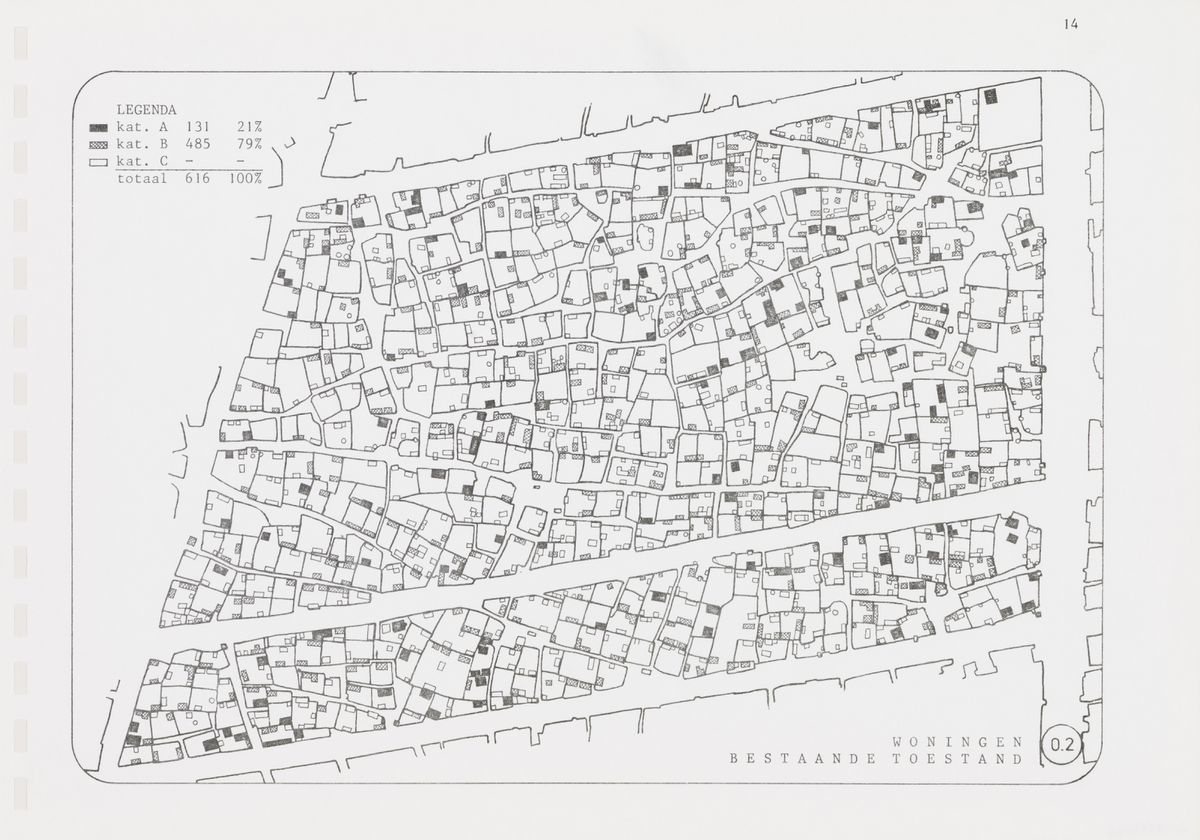

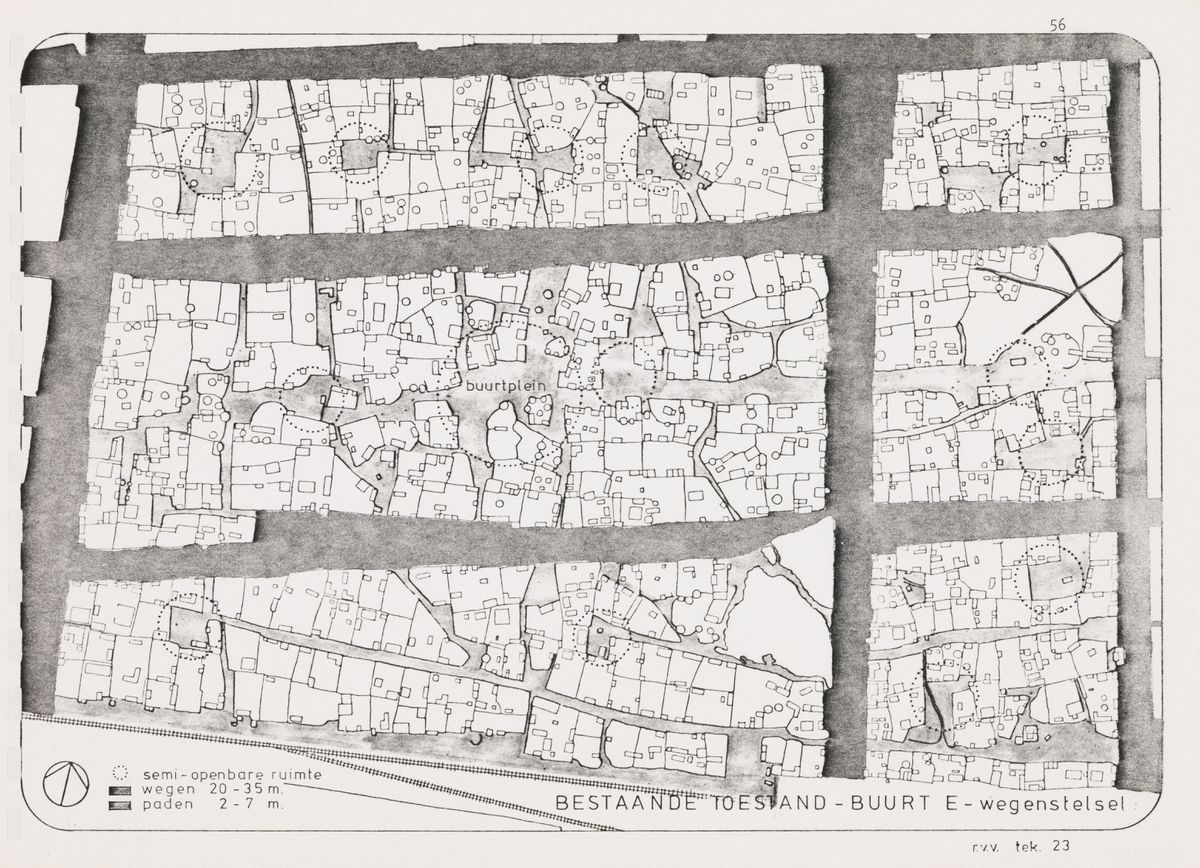

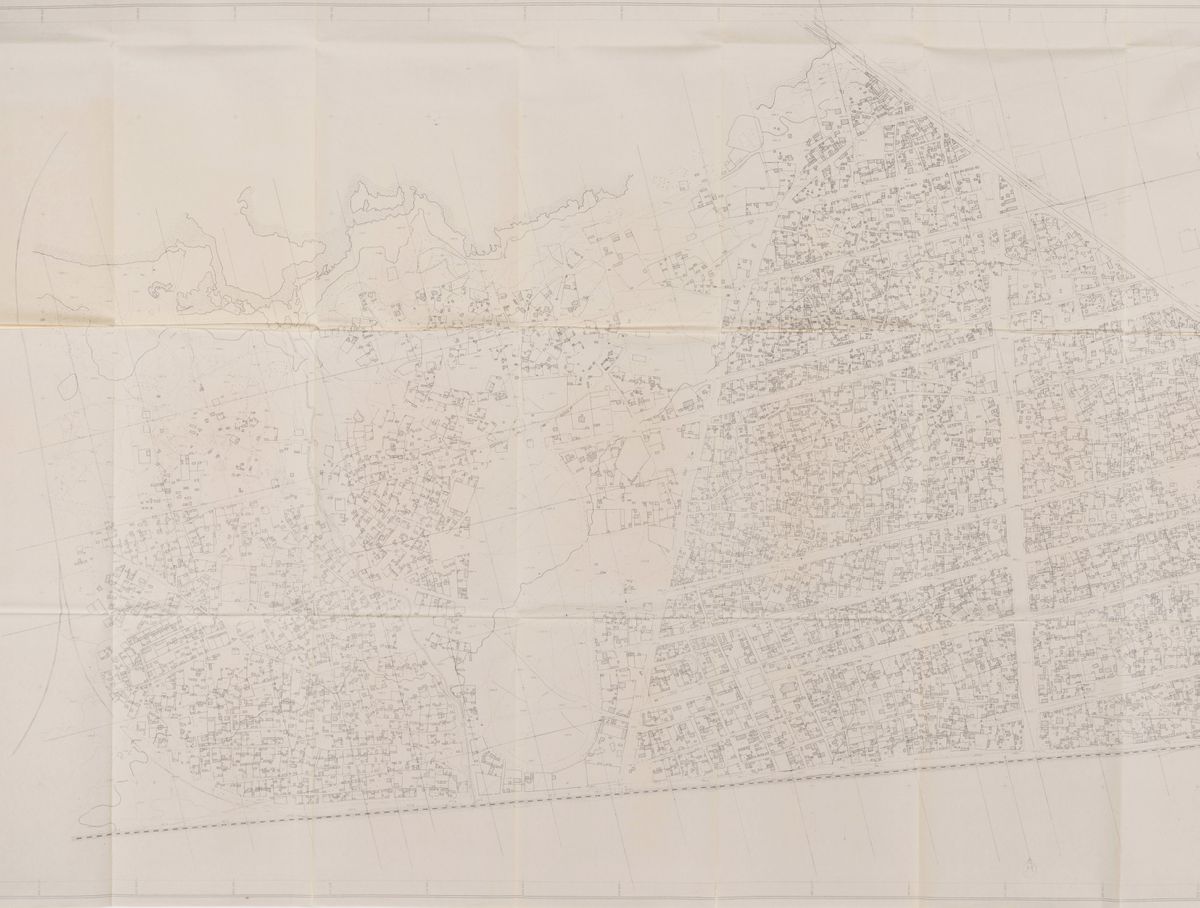

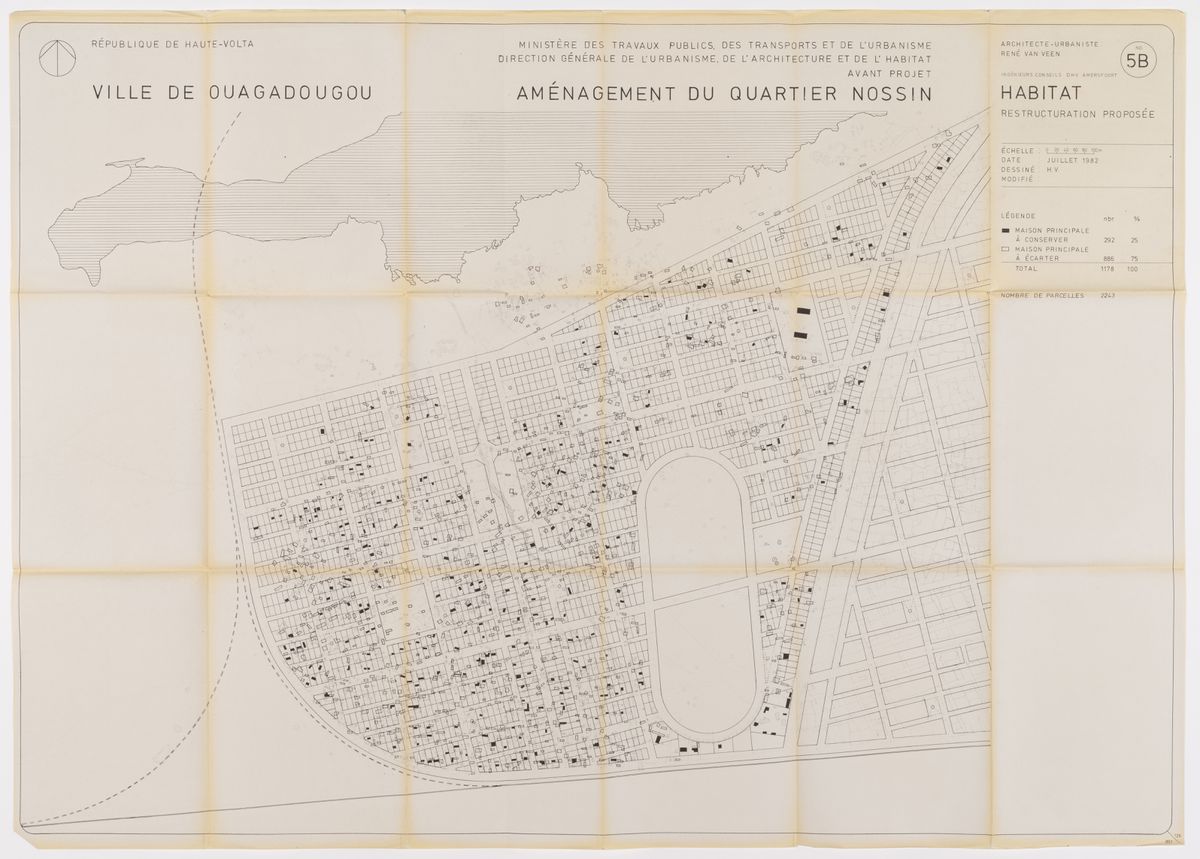

In the early 1980s, the informally occupied areas that surrounded Ouagadougou’s city centre had no basic services or infrastructure. For local authorities and international aid organizations, this situation presented an increased risk of urban congestion and slum development. While Beeker’s pilot project focused on only one neighbourhood, he was already working to convince local authorities to adopt a more holistic and long-term vision for Ouagadougou’s territorial development. Aerial photographs taken in 1978 by the Institut Géographique de la Haute Volta (Geographic Institute of Upper Volta) provide an overview of Ouagadougou’s unallotted areas. Using these images, Beeker’s team was able to produce drawings and maps that illustrated, for the first time in Burkina Faso’s history, the presence of spontaneous settlement areas and the scale of their spatial influence on the city’s peripheral regions. By combining their analysis of aerial photographs with site visits, the team was also able to map the area’s morphology and built environment. This evaluation of existing urban conditions was aimed at producing the most coherent development proposals possible given the urban and social fabric of the city.

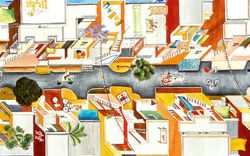

As an object, the map is both a communication tool and a political lever. Demonstrating the existence of spontaneous settlements in a tangible, spatial way helped establish the social reality of habitation in a given territory, and was an important first step in Beeker’s project for popular participation. Residents from the neighbourhoods represented were then invited by Beeker’s team to give feedback on various proposals for the organizational structure of their neighbourhood, among which a majority chose the orthogonal grid. This grid model was then proposed to Ouagadougou officials to help guide the redevelopment of the city’s unstructured areas. Eventually, the project’s beneficiaries were called in to help carry out the work by laying out their plots and by building their own housing, if necessary. Traditional leaders were also given an important role in planning, managing and supervising the field work.

Through numerous progress reports and extensive correspondence, Beeker’s archives document the direct cooperation between Dutch urban planners and researchers, and the political authorities of Burkina Faso. As the project’s initiator and coordinator, Beeker focused on involving the local government, unlike many expert-led international development programs from that era, which worked independently from local governance structures. Beeker also conducted much of his work during regular trips to Burkina Faso, while a local team from Ouagadougou supervised the project’s daily operations.

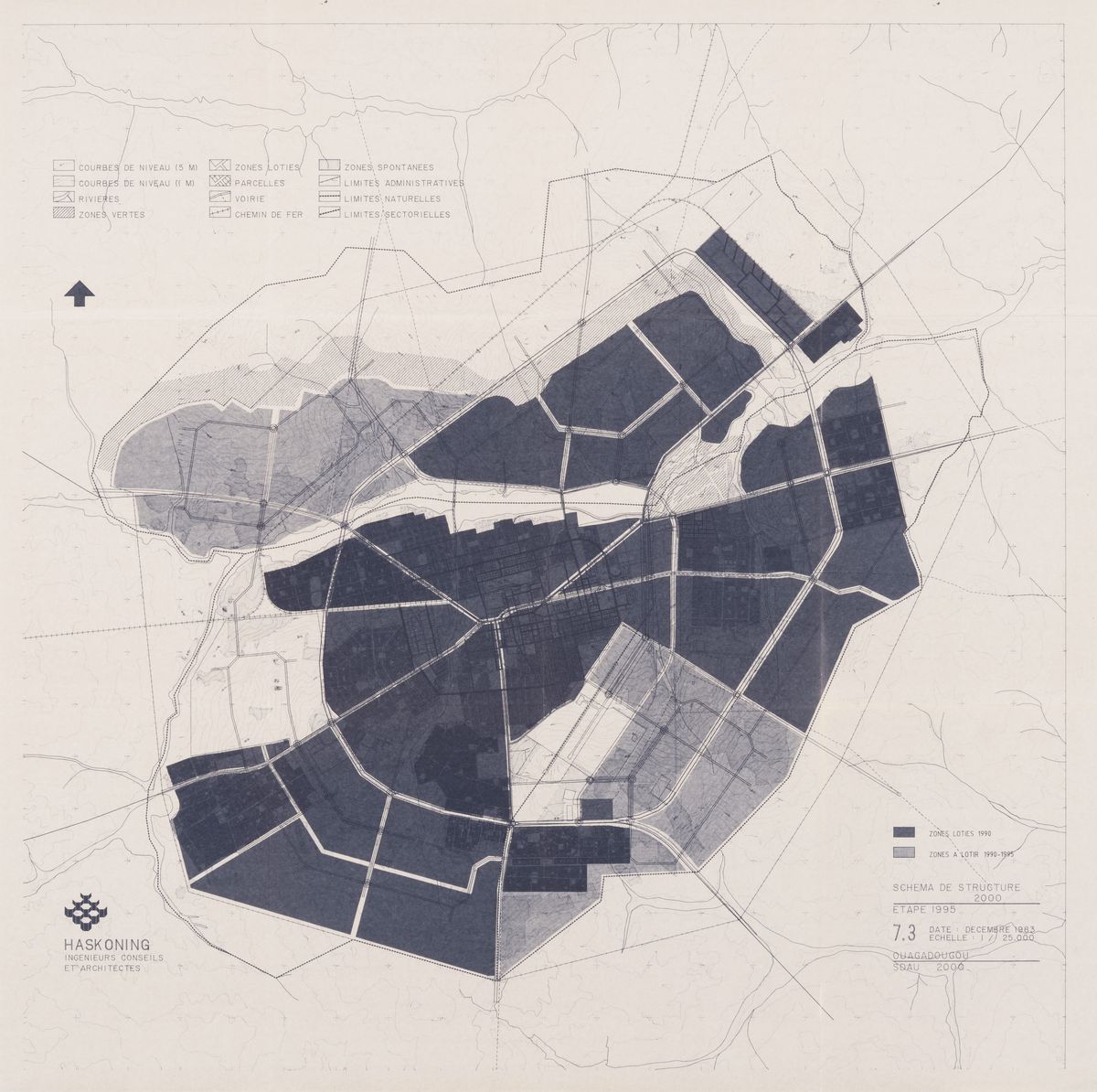

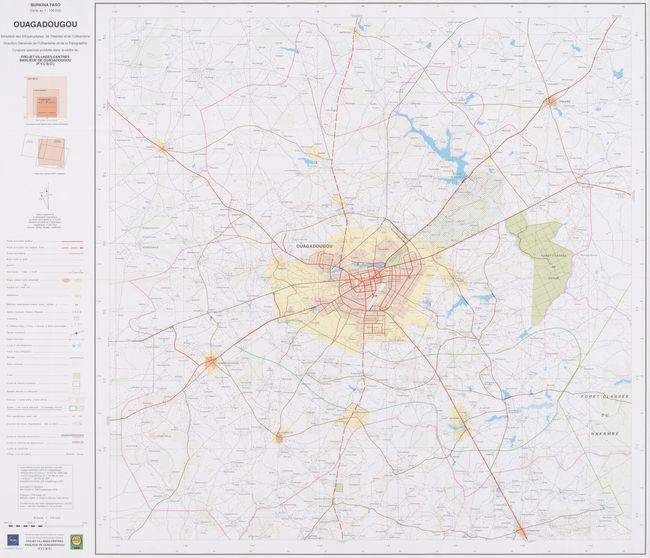

Sankara’s rise to power in the summer of 1983 was a key moment in Burkina Faso’s sociopolitical history, and saw a metamorphosis in the urban vision of Burkinese officials. The Sankarist political agenda sought to radically transform social relations by relying on the power of the masses, and implementing nationwide modernization in which citizens were encouraged to participate in major projects. Sankara also adopted a broad-based approach to regional planning and quickly prioritized the management of unstructured areas. Some 250,000 residents—nearly half of Ouagadougou’s total population—lived in spontaneous settlements on the edges of the capital’s lotted core.1 For Ouagadougou’s urban plan in 1983, Sankara adopted the Programme Populaire de Développement (PPD), which adhered to Coen Beeker’s vision and the application of the MAP within a nationwide allotment program.2 In keeping with this, the Dutch firm Royal Haskoning produced an Urban Development Master Plan (SDAU) for the Direction Générale de l’Urbanisme et de la Topographie du Burkina Faso (Department of Urban Planning and Topography, DGUT).

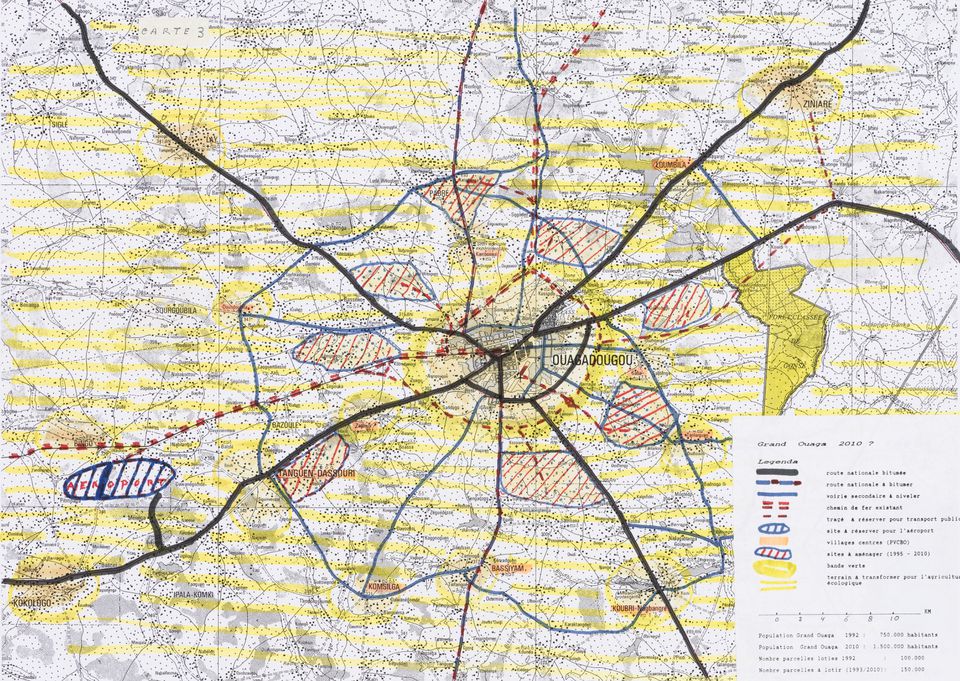

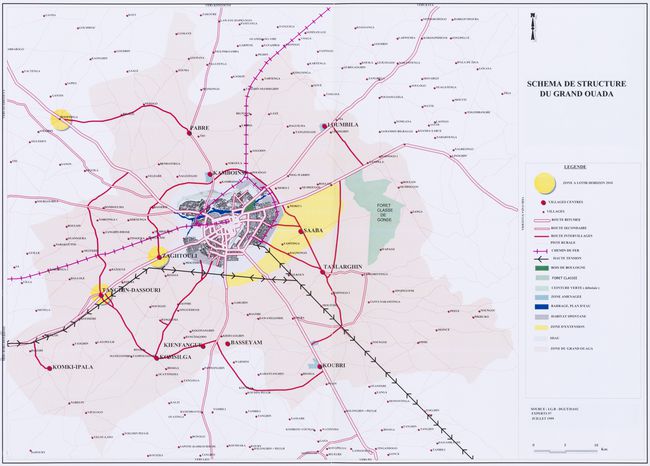

The SDAU is an important document that presents short, medium and long-term development plans for public facilities and infrastructure in Ouagadougou, with the stated goal of channelling and curbing the expansion of spontaneous settlements. By looking at various maps and observing the expansion of urbanized areas towards the periphery of the city, we can see how the DGUT implemented proposals from the SDAU once it was finalized. In a still largely rural country, Sankara’s mission was to transform Ouagadougou, the country’s main urban centre, into a modern capital that would act as a showcase for the ambitions of the state.

The implementation of the SDAU indicates how Beeker’s vision for Ouagadougou’s spatial organization was appropriated by the Sankara administration for projects such as the Projet-Villages-Centre-Banlieues de Ouagadougou, or even the Schéma d’Aménagement du Grand-Ouaga, an extension of the SDAU.

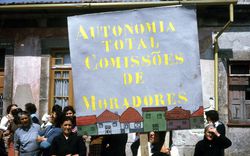

In the Sankarist political program, rural populations played an important role in the construction of the Revolutionary project, formalized in Sankara’s Political Orientation Speech, delivered on October 2, 1983. But a prominent place was nonetheless reserved for the Comités de Défense de la Révolution (CDR), committees made up of radical militants and implemented with the advent of the new government.1 The CDR acted as local administrative managers and oversaw urban development at the neighbourhood level. Their designated role was to act as a conduit between the will of the people and political authorities, and to represent citizens in the decision-making process.

Sankara needed the full cooperation of the masses to realize his ambitious plans for health, education, and land development. He was enticed by Beeker’s subdivision method, which relied on the involvement of locals, favoured the political rehabilitation of marginalized populations within the urban context, and proposed a simple orthogonal road grid. The Burkinise leadership appropriated Beeker’s MAP, but transformed two of its major elements for its large-scale subdivision program.

First, the citizens of Ouagadougou were mobilized as the builders of Sankara’s new city, with the PPD emphasizing self-reliance while requiring the execution of common-interest elements, such as infrastructure and the construction of public facilities. At the same time, since the orthogonal grid was adopted for roads in all future spontaneous settlements and systematically applied as part of a pre-established plan, participants lost their role in the planning and consultation process. The term “participation” hitherto reworked in political discourse to become an obligation to collaborate as a volunteer labour force in the implementation of state development projects. Moreover, under the Sankarist regime, any opposition to Sankara’s political project was considered counter-revolutionary and subject to political sanctions, inhibiting the very process of participation which normally involves a series of conflicts and negotiations.2

In this sense, the evolution of the allotment project during the Sankarist regime from 1984 to 1987 is illuminating. The speed and scope of the city’s development could only have occurred at the expense of public consultation on the restructuring process, in parallel with considerable involvement from the masses in its implementation.

Despite the absence of public participation planning documents, numerous reports and maps from the CCA’s African Architecture Matters Collection reflect a decline in public participation in the Sankarist program, corroborated by the rapid subdivision of more than 60,000 parcels of land bordering the city of Ouagadougou in less than five years.1

Coen Beeker’s professional archives help illustrate the malleability of the notion of participation, and how its application within the Méthode d’Aménagement Progressif allowed different regimes to shape the concept according to their own political agendas and visions of Ouagadougou’s urban space.

-

See also Sylvy Jaglin, “Pouvoirs urbains et gestion partagée à Ouagadougou : équipements et services de proximité dans les périphéries” (PhD diss., Université de Paris VIII, 1991). ↩

Philippe Genois-Lefrançois developed this research as part of the 2017 CCA Master’s Students Program. This program offers students an opportunity to use the CCA collection during a summer residency. In 2017, it focused on the African Architecture Matters Collection, recently arrived at the CCA.