Temporal Conjunctions

Peter Sealy discusses pastoral imagery in contemporary representations

Villa Além

The walls enclosing Valerio Olgiati’s Villa Além (2014) define a lush precinct in Alentejo, a dry region of southern Portugal. Tilting either outward or inward, they welcome and protect the visitor within the private domain inhabited by Olgiati, his partner, and their guests. Olgiati’s Instagram feed frequently features photographs of the garden enclosed within these walls, a garden that transforms the Villa Além into a verdant set of metaphors: ark, oasis, haven, etc. Olgiati’s buildings share a brilliant ambiguity: while every detail has clearly been thought through by its designers and constructors, the overall effect is archaic, timeless, and seemingly unauthored. Though materially an organic counterpoint to the mass of Olgiati’s usual concrete forms, the garden follows the same ambiguous logic. Obviously, these plants did not arrive there by accident, but as they grow larger any apparent causality is soon blurred. Have they thrived thanks to the Villa Além’s nurturing enclosure, or was the villa built to capture them? Surely one day the garden will devour the villa, a day that becomes easier and easier to imagine as the plants thrive and our current sense of emergency intensifies.

While photographs (both professional and personal) have documented the garden’s evolution, another image brings it into more evocative focus. Created by Valerio Recchioni, this digital image shows two women walking in the Villa Além’s garden under the welcome shade of a parasol. A golden wheat field punctuated by red poppies fills the lower half of the image, balanced by a bright, yet cloud-filled sky above. A shallow pool of maize-coloured water glistens in the foreground under the burning midday heat. The effect of these feminine flâneurs—in fact, the image’s entire aesthetic—is clearly drawn from Impressionist painting’s visual lexicon. Searching the image, the viewer’s eyes identify the incongruous presence of the Villa Além’s rectilinear walls.

Recchioni’s image was first published by afasia archzine on 29 October 2020; it was later re-posted on Instagram by Olgiati himself. In it, the artist transports the Villa Além back in time, to the Belle Époque, with its bourgeois tourists exploring southern, sunlit countrysides to escape the psycho-physiological and aesthetic ills of industrialization. Recchioni does so by placing the Villa Além’s garden walls within the scene depicted in Giuseppe De Nittis’s 1873 painting Nel Grano [The Wheat Field]. Formally, the incongruous conjugation of Olgiati’s villa and De Nittis’s painting identifies the garden walls as a frame, a container that divides internal and exterior landscapes. While the Villa Além includes spaces from which Olgiati can work, the garden is meant as a space for carefree leisure of the sort depicted in Nel Grano. As viewers, we are left to wonder what the two women are discussing.

The New Pastoral

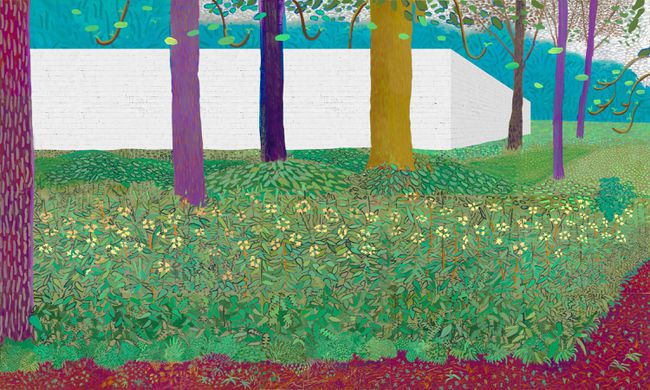

Recchioni’s fanciful representation of the Villa Além belongs to a recent series of architectural images that depict contemporary projects in painterly settings. In the case of Office Kersten Geers David Van Severen’s Solo House (2012), the use of David Hockney-esque images is quite realist, in both form and content. The circular house’s location, on a plateau in a mountainous region south of Barcelona, is depicted with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The chosen painterly style—and the relaxed figures in the house’s enclosure—clearly imparts a vision of the house as a space of fauvist leisure, tinged with the ennui of modern life. Representations of fala atelier’s A Garden with White Walls (2013), a sports facility for the University of Porto, display a similar painterly approach. This time, images reminiscent of Van Gogh emphasize the precinct’s intermediate spaces, reimaging them as a space of bourgeois distraction.

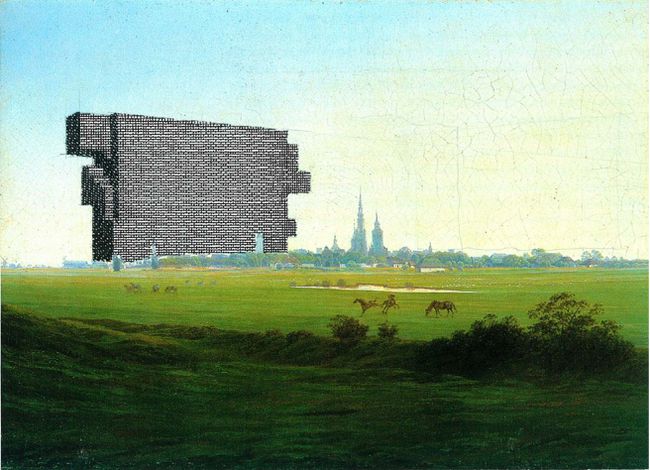

Dogma has also adopted a painterly approach to representing their polemical attempts to constrain the forces of late capitalism within the boundaries of architectural forms. This is the case with several of the representations for A Simple Heart, Architecture on the Ruins of the Post-Fordist City (2002–9). The result—in images of Immeuble Cité (2004), for example—is a contrast between an unspoiled, pre-industrial world and a massive intervention whose incommensurability is meant to guarantee the survival of the setting that it now dominates.1 The linear tower of Immeuble Cité fills part of the background to Caspar David Friedrich’s Meadows near Greifswald (ca. 1822). The resulting image is quaint in its suggestion—false in this case—that the pre-industrial social and cultural relations of Friedrich’s hometown still exist to be preserved through such an operation.

-

Olgiati’s unrealized plan for three towers housing vacation homes in the Cuncas area of the Engadine does the same thing. ↩

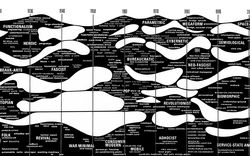

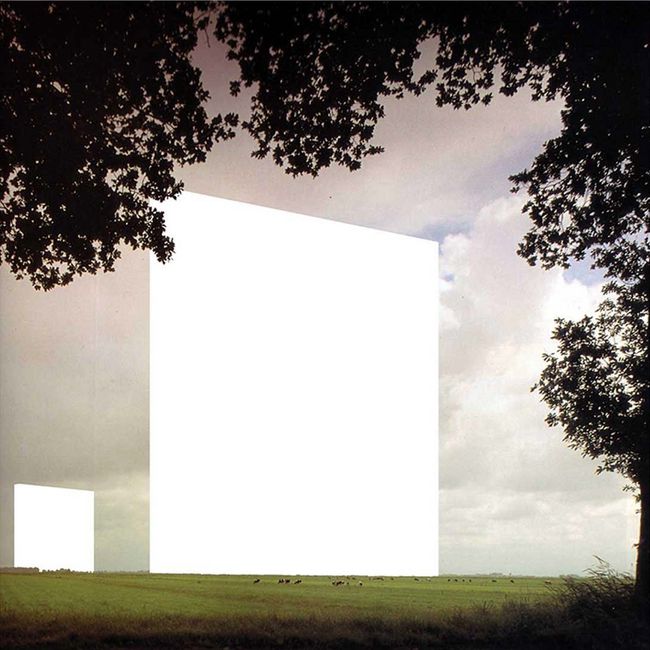

Dogma claim the project Stop City (2007–8) is an “architecture without attributes…an architecture that is freed from image,” yet—in a paradox common in modernity—this assertion can be made only through seduction and imagery.1 By positioning eight slab towers measuring five hundred metres by five hundred metres by twenty-five metres around a forest three kilometres wide, Dogma seeks to use gigantism in order to establish limits to urbanization.2 In spite of Dogma’s claim to have produced an architecture without qualities, we know very well what the deliberately indeterminate white forms seen in the drawing will really look like. This is an attempt to recover the modernist slab tower at its largest possible size in order to implement a totalizing and generic urban condition, one in which immutable forms house fluctuating functions. While Dogma seeks to put an end to modernist faith in urbanization, such imagery again posits a pastoral “other” to be protected from encroachment, just as was to be found in garden city suburbs and even Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris, which promised to cover the ruins of the bourgeois city with greenery. Is the pastoral being preserved, or is it being conquered? In relationship to its surroundings, the white slab tower resembles nothing so much as the first apparition of the monolith in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). This totalizing impulse can also be seen in Superstudio’s drawings for the Continuous Monument (1969–70). Again, we may ask whether the unceasing bar, meant to unify the earth’s disparate urban and rural landscapes into a stable and nurturing cosmic order, does not instead symbolize the former’s techno-political dominion over the latter.

This shocking juxtaposition of nature and culture is also found in Hans Hollein’s Aircraft Carrier City in Landscape (1964). Aircraft Carrier City was part of Hollein’s series Transformations, which used photomontage to generate unlikely juxtapositions between industrial objects and landscapes.1 In an iconic image, the imposing hulk of an aircraft carrier dominates a gently rolling landscape, which seems to have been chosen for its incongruity as a setting for such a behemoth. Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture (1923) famously presented visual confrontations between machines and works of classical architecture; Hollein’s goal was not to support a particular (modern) architecture, but rather to claim that “everything is architecture.” In fact, while the viewer’s focus is naturally drawn toward the warship—as much an urban artifact as anything else produced in the twentieth century—Hollein’s own vision evolved to see the landscape itself as profoundly architectural. Thus it is the rolling hills and not the aircraft carrier that give the image its ultimate meaning.

Just as they belong to a historic lineage including Hollein and Superstudio, these pastoral images by Office, fala atelier, and Dogma also belong to a wider tendency in twenty-first-century architectural representation that counters the commodified photorealism of the computer rendering. With the advent of advanced image-making software, the cutting edge of architectural rendering has become visually indistinguishable from the imagery now found in video games and other media that blur representation and reality. Within architecture, the hyperrealist rendering has moved from the avant-garde to the banal world of developers’ condominium projects.2 This has left the former searching for new means of expression, leading to a flattened, often colourful and collage-like vision of architecture, one that has been associated with a supposed return of postmodern aesthetics and image consciousness.3

-

Matilda McQuaid, ed., Envisioning Architecture: Drawings from the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2002), 146–47. ↩

-

For the avant-garde engagement with digital image-making, see the exhibitions and publications in the CCA’s Archaeology of the Digital series, as well as the research conducted in the Mellon Foundation-sponsored CCA research project Architecture and/for Photography. ↩

-

On this “post-digital” drawing movement, see Sam Jacob, “Drawing in a Post-Digital Age,” Metropolis 36, no. 8 (2017): 76–91. ↩

What Hath God Wrought?

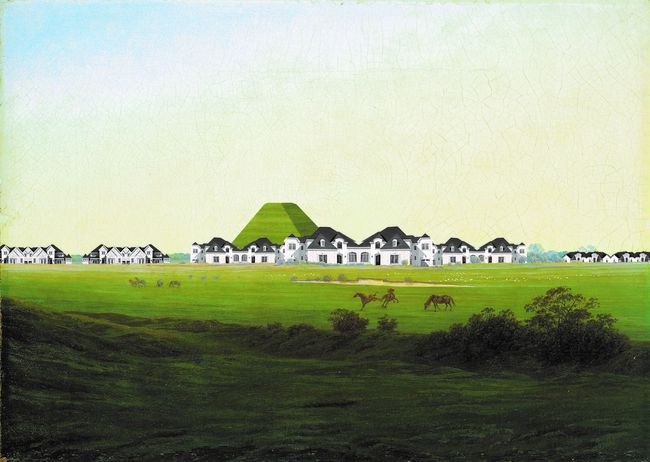

The images in Keith Krumweide’s satirical book Atlas of Another America (2016) fictionalize a world—“Freedomland”—in which the McMansions of American exurbanization are repurposed for communal housing. Forms are shown to be transferable across ideological regimes, as the dystopia brought about by financialization inhabits its totemic vestiges. Eschewing explicitly revolutionary imagery for such a radical project, Krumweide’s images reposition contemporary developer housing within historical paintings. Thus, Freedomland’s houses are shown in Friedrich’s Meadows near Greifswald and Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (1750). In the former painting—the same one used by Dogma for A Simple Heart—Greifswald itself has been replaced with groupings of McMansions, behind which a truncated green pyramid looms. While the image’s many triangular forms may harken to the illustrations for Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s Ideal City of Chaux, the result equally seems to be an illustration of Joni Mitchell’s iconic lyric “they paved paradise and put up a parking lot.”1

Mr and Mrs Andrews had been an attempt by Gainsborough to combine his love of landscape views with a reluctant acceptance that what he termed “face painting” (i.e., portraiture) was more lucrative. Krumweide’s appropriation of this painting creates a new juxtaposition, this time between the Andrews as members of the eighteenth-century landed gentry and the homes of their class progeny in the twenty-first-century United States. Intriguingly, Krumweide has maintained the unfinished spot on Mrs. Andrews’s lap: it was unknown if this space was reserved for an as-yet-unborn child, a pheasant, or perhaps a book. The gap reminds us of the constructed nature of these images and suggests that Krumweide’s insertion belongs to an authentic tradition of productive manipulation that includes Gainsborough himself.

As critiques of contemporary conditions, utopias have often been set in idyllic, pre-urban landscapes: this was the case with Charles Fourier’s phalanstery and Robert Owen’s New Harmony. Krumweide has described his project as “bastard lovechild of Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier,” melding competing urban and agrarian traditions.2 While contributing to the overall effect of satire, the use of recognizable masterpieces for Freedomland’s imagery harkens to an American tradition of acculturation that includes, Pierre l’Enfant’s plans for Washington, DC, and the City Beautiful movement.3 As Manfredo Tafuri noted, the United States has often adopted the retrograde cultural forms of the same autocratic European societies which American democratic capitalism had superseded: “In Washington, the nostalgic evocation of European values was concentrated in the capital of a society whose drive to economic and industrial development was leading to the concrete and intentional destruction of those values.”4 The heart of Krumweide’s satire can thus be understood as a critique of the original sin of American development.

-

Looking elsewhere for a historical reference to anchor our understanding of the image, we may wonder if the McMansions’ bastardized classicism can be linked to the appropriation of Biedermeier forms in the 1950s by East German architects seeking to create communal buildings that would be “national in form, socialist in content”… but the connection is tenuous at best. ↩

-

See, for example, the curatorial text for Freedomland, an exhibition Krumweide mounted at WUHO gallery, in Los Angeles, in 2012. ↩

-

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976), 30–40. ↩

-

Tafuri, 34. ↩

“What hath God wrought?” was a commonly asked question in the antebellum United States, as the citizens of the early republic followed the westward course of empire. Picturesque imagery was crucial to this process of self-actualization. Notice the steam engine, railroad tracks, and imposing roundhouse in George Inness’s painting of the Lackawanna Valley on the cusp of industrialization, around 1855. Commissioned by a railroad president, this view of Scranton, Pennsylvania celebrates the advance of technology while lamenting its impact upon nature. The early American republic strove at great cost to achieve the harmonious balance of industry and agriculture, rural and urban, old and new brought about by Inness’s brushstrokes. If his painting shows a virginal landscape not yet despoiled, Atlas of Another America shows an America still coming to terms with the changes brought about by the “manifest destiny” revealed in images such as Inness’s.

An Atemporal Conclusion

Read ungenerously, images such as Recchioni’s Impressionist view of the Villa Além may seem like a dangerous aestheticization of the current ecological emergency in which a new landscape, a past temporal moment, and even a different climate can be conjured up using pictorial techniques. Or perhaps it belongs to a striking pessimism in recent urban discourse—driven by soaring house prices and feelings of helplessness in the face of NIMBYism—that has only been amplified by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. This urban pessimism (misplaced as it may well be) finds a pendant in age-old conceptions of the countryside as a retreat from the ills of the modern city. Recent architecture exhibitions seem to have identified the countryside as territory ripe for annexation by their research agendas. In reproducing forms from nineteenth-century western art, is a colonial attitude, such as the one Inness depicted, also reproduced? Surely the authors of today’s pastoral images would recoil from such readings, but they do reflect the extent to which iconography is never neutral.

For Recchioni’s image, such a reading would also ignore the trajectory of Olgiati’s own practice in his native Switzerland. While the Villa Além is undoubtedly rural, it belongs to series of projects that expertly negotiate between public appearance and individual privacy in a fundamentally urban way. The Atelier Bardill (2007) in Scharans provides a prime example of Olgiati’s capacity to amplify the public realm through the creation of a private enclave.

Beyond this alibi—which belongs to Olgiati’s buildings and not their representation by others—there is another far more emancipatory reading of Recchioni’s image, one that embraces architecture’s full iterative capacity. Rather than seeing this image as an escapist denial of present realities, we can see it as an opening onto a world of alternative futures, one that makes self-evident the contingency of the present. Not only do the Villa Além’s garden walls enclose their own flora; in Recchioni’s image, they surround a distinct slice of time extracted from De Nittis’s painting. The very stability of Olgiati’s forms—and their claims to an archaic atemporality—are shown to paradoxically enclose a time machine.

A similar asynchronous composition of building and setting can be found in the digital collage Johnston Marklee used to illustrate the Hill House in Los Angeles (2004). Johnston Marklee’s use of Julius Shulman’s iconic 1960 photograph of Pierre Koenig’s Stahl House as a background for the Hill House is whimsical yet logical given their shared hillside settings: their collage only makes evident an obvious typological connection. Beyond the subtle differences in architecture (the Stahl House is an exercise in transparency; the Hill House’s opaque forms frame views in a far more self-conscious manner), we are left with a temporal puzzle. Has the Hill House been transported back into the glamorous domestic atmosphere of mid-century California modernism, before its prevailing gender roles became outdated? Or have the women peopling Shulman’s photograph been brought forward in time—without aging at all!—to find themselves once again objectified in architecture?

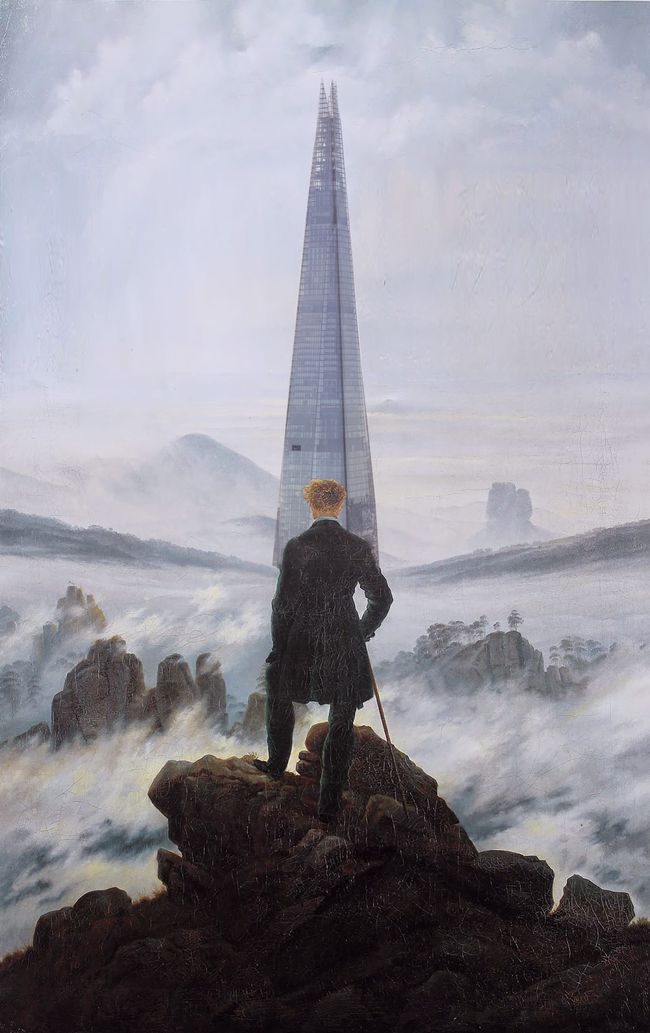

Recchioni’s Villa Além collage belongs to a larger series of caprices entitled Genius Disloci (2017–).1 In producing this series, Recchioni asks a simple but enigmatic question: “What would happen if some of the most famous works of art had to live with the architecture of our time?” Thus the figure in Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of fog (1818) now gazes upon Renzo Piano’s Shard and the entrance to Carlo Scarpa’s Brion Tomb (1978) frames the dark forest from Dante’s Inferno by Gustave Doré (1857). For Recchioni, the answer to the question is simple: the productive juxtaposition of buildings and paintings make visible points of similitude and dissimilitude between past and present. Rather than corrupting original works, such collages allows us to better interrogate, understand, and appropriate them.

Today, architecture appears to unfold as a stream of images, visual pinpricks offering a few seconds’ distraction within the contemporary digital environment. We quickly click “like” and then scroll through space and time to the next image. Instead of seeing this state of affairs as frivolous at best, dangerous at worst, we should engage seriously with the potential of architectural images—which can now be made by anyone with access to a computer and disseminated globally on the internet—to bring about radical spatial and temporal juxtapositions, such as those proposed by Recchioni and others. The Impressionist pastoral settings for contemporary architecture discussed in this essay, whatever the meanings intended by their authors, are but one example of the world-making potential latent in architectural representation.