Building a Forest

Noelia Monteiro on the exercise of observing

Observation is a practice that binds architecture and research. In architecture, it links the construction of inhabited space with the everyday practices and technical knowledge that sustain it; in research, it becomes a method to reveal how these practices and techniques generate new possibilities for design. In the Amazon, the most biodiverse region on Earth, observation reveals how the spatial heritage of Indigenous landscape designs continues to shape and protect the forest’s fragile edges, offering valuable lessons for future projects that aim to care for both people and the environment.

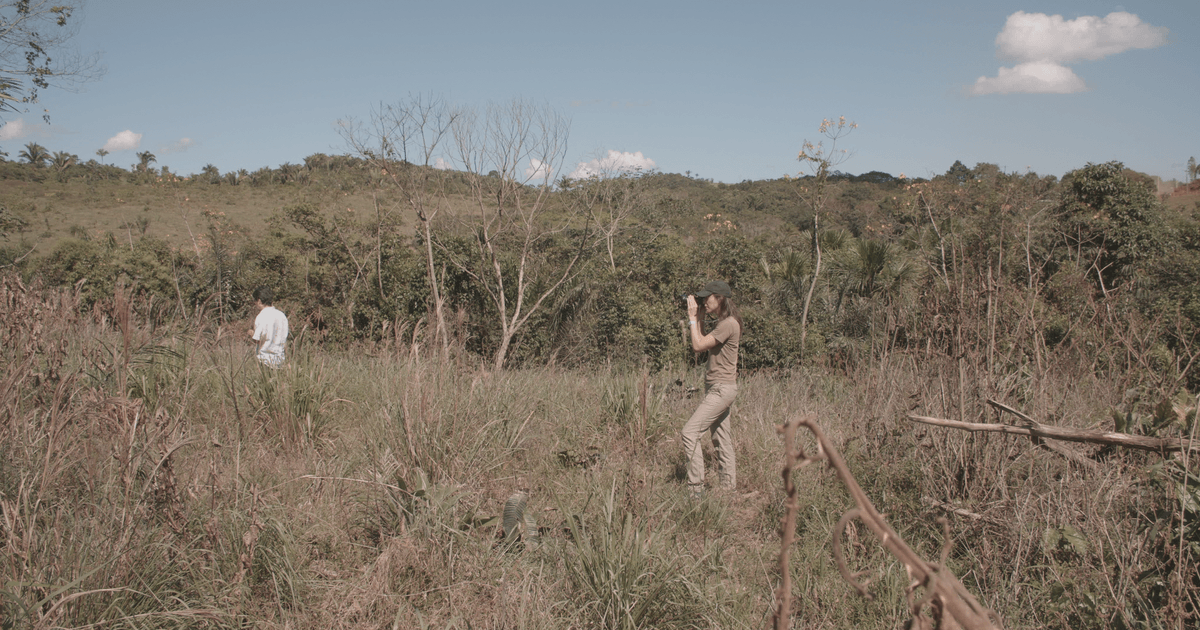

With Estudio Flume, I arrived in the municipality of Apuí, Amazonas state, on 15 June 2025 after an extensive twelve-hour trip from Porto Velho, the capital of Rondônia state. The journey, postponed since March due to heavy rains that blocked road access, was made possible this time by two ferry crossings: first over the Madeira River, then the Aripuanã River. The road stretched between forested areas and open clearings, as if already announcing the complex agricultural condition that marks this territory. We reached Apuí to initiate the design of the Agroforestry Centre and Forest Observatory, a project that seeks to value and strengthen local practices that care for the land; the result of years of dreaming, working, and researching.

Over the course of the twentieth century, the Amazon was transformed from an economy based on low-impact local extractivism to one centred on large-scale agriculture, livestock, and agribusiness—a transition driven by national programs with the opening of the Transamazonian highway in the early 1970s, during Brazil’s military dictatorship. The impact of this transformation can be felt in the municipality of Apuí, and our journey there was a deep immersion that revealed both the potential and the contradictions of the region. During our stay, our observations expanded beyond the landscape and the forest, and into the voices of the people who inhabit Apuí. It became clear that large portions of the Amazon rainforest are not natural, but cultural.

The text that follows offers a collection of insights gathered through interviews with the community living along the Juma River, who each contribute in their own way to the complex social and cultural system of the region. These narratives and experiences teach us not only about the power of community organization for agricultural development but also about the challenges faced by the forest and the soil, highlighting the importance of local knowledge and sustainable practices to preserve and renew this vital territory. In more than forty years of inhabiting the region, these families have created roots, friendships, and stories that span generations. This capacity to observe, to learn along the way, and to organize collectively is at the heart of our efforts in creating the Agroforestry Centre and Forest Observatory. The experience and resilience of those who live in the forest are also the key to its preservation.

Antônio is a farmer who migrated from southern Brazil in the 1980s after hearing the government’s call to occupy the Amazon on the radio in Francisco Beltrão, Paraná state. At the time, programs such as Operation Amazon and the National Integration Program encouraged migration to the north of the country, offering fertile land and the idea of a prosperous agricultural frontier. The National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) provided one and a half cubic metres of planks and one cubic metre of timber, along with fifty tiles and twenty kilograms of nails, for families to build on plots of one hundred hectares intended for establishing their food crops.

Lucia arrived a little earlier. Her memory is marked by the visual impact of the road: “So much brush, so much brush. The road looked like a tunnel; it didn’t look like a road. It was beautiful below but closed above. Luckily, we were given a little house to live in until we managed to get our own.” At that time, living conditions were precarious, and adapting to the environment required great resilience. It took Lucia seventeen days of travelling in a moving truck to get there. What is most striking in her account, however, is the strength of the community organization that followed. Through the creation of an association for coconut production, residents were able to get the materials they needed to succeed in planting: “They were all producers who wanted to work, but had no machinery, no truck, no dryer, nothing. Through the association and the bank, we managed to get all of that.”

In our conversation with Leoni, who also arrived in Apuí with Antônio more than forty years ago, she recounted a moment from her journey: parched with thirst after days of travelling by truck, she remembers seeing Lucia sweeping the street as they entered what was then only a small village. Exhausted from the heat and the long journey, Leoni and her family were offered water and hospitality by Lucia, and the two have remained friends since. Despite the generosity, conditions were harsh, and the children were exposed to diseases like malaria. At that time, there was no health infrastructure, only a mobile medical service, which mainly supported the workers of infrastructure projects like the roads that were beginning to carve paths through the forest. She recalls the difficulties of securing land to live on and the collective effort to build their houses with the few resources they had.

The second generation to arrive at the Rio Juma settlement—the INCRA’s largest agrarian reform project, which aimed to accommodate 7,500 families—has now returned to care for its roots. Many from this new generation left to study and today, through their different areas of specialization, form the multidisciplinary team that sustains the Agroforestry Centre and Forest Observatory project. This dialogue and continuity between generations is vital to ensure that the project encompasses both the experiences of those who arrived forty years ago and the critical energy of those returning with new knowledge, to build not only a physical space, but a living territory of research, production, and socio-environmental care.

Adalberto, who came back to Apuí to work at INCRA, shared the record they have been compiling over the past eight months: a socioeconomic and occupational survey in Gleba Juma intended to break down the current state of small producers in relation to the time of the settlement’s implementation in 1981. This diagnostic study seeks to build a detailed picture of land tenure, production, and social reality, mapping what is being produced, the difficulties faced, and the documentary conditions of the producers. The work faces challenges, among them the resistance generated by Brazil’s polarized political context and the specific territorial conflicts within what is now one of the main focal points of the so-called “arc of deforestation.”

The continuity of the work of the second generation of the Rio Juma settlement is also manifested in the role of specialists such as Domingos, who translates this knowledge into specific actions for environmental restoration. Domingos works at Prevfogo, a federal government program under IBAMA (the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), which focuses on fire prevention and the production of native seedlings, essential elements for the reconstruction and preservation of fertile soil and local biodiversity. During our conversation, Domingos shared how he has observed the growing severity of fires, aggravated by prolonged drought and deforestation. “Fire is already natural, but since I joined the program in 2008, I’ve noticed that our climate has been drying out more and more. Last year was historic, with fire reaching into the forest, something rare here, due to increased deforestation and reduced humidity.” This work of prevention, seedling production, and firefighting, combined with local practices and the network of small producers, demonstrates how vital it is to unite technical and traditional knowledge in order to protect and restore the Amazon rainforest.

Shuely, a young small-scale farmer, embodies the strength of the empirical knowledge of a new generation who learn directly from the land and resists the pressures of agribusiness daily. Like others, she seeks support to conserve her property through diverse planting that enriches the soil, serving as both subsistence and income. She learned through practice, in the rhythm of trial and error, how to cultivate more sustainably. Shuely also understands the vital importance of maintaining the forest to conserve natural water sources. “If there is no water, there is no life; nothing grows.” Similarly, Diomar, also a farmer, shared the effort of learning without formal support. Together with Shuely, he engaged in a practice of observing, copying existing models, and adjusting them through trial and error to build greenhouses that withstand the climate. This trajectory reveals the determination and creativity of small farmers in building their own solutions, learning by doing, and nurturing family farming in the region.

Apuí is also shaped by knowledge transmitted from generation to generation, the patient observation of nature, and the entanglement of migrations. Until the age of fifteen, Darcy learned from his grandfather, a German migrant to southern Brazil in the interwar period, how to observe nature for planting, to follow the cycle of trees, and to produce seedlings. Following the flow of displacements that has marked the recent history of the Amazon, Darcy left Chapecó, Santa Catarina state, and migrated to Apuí forty-two years ago. Today, at the age of seventy-six, he has dedicated his life and resources to producing native seedlings for reforestation. All the knowledge he has accumulated, the fruit of decades of meticulous observation, he now shares with his granddaughter Tainara, an agronomy engineer trained at the Federal University of Amazonas in Humaitá, who will continue to care for the tree nursery in the future.

During our conversation, Darcy described with precise ways that trees announce climate change: copaíba, which once bloomed in August and September, now blooms in October and November. Jatobá also no longer follows its former rhythm. He explains that “trees have to defend themselves,” and only those who closely observe notice the shifting of these cycles. Darcy keeps detailed records of eighty-four native species, tracking flowering, seed production, and the location of trees. This costly and persistent work results in the production of thirty thousand seedlings per year, cultivated in his tree nursery, a living archive of ecological knowledge. Darcy’s experience and the generosity with which he shares years of work reinforce the power of observation as a tool of knowledge, care, and resistance in the face of climate change.

Raimundo has been working with Darcy for several years. He was born in Nova Olinda, and when he moved to Apuí, he noticed an environmental imbalance that differed from the riverside community where he grew up: land in the area would not regenerate. Raimundo guided us into the forest to a copaíba tree and, standing before it, shared his experience of extracting its oil, a practice that demands patience and care. He explained that the process begins with observation: “You have to tap the trunk to hear its sound. If it doesn’t have oil, there’s no point in drilling.” Only after identifying the right tree does the harvester bore the hole, collect the oil, and finally close the opening with wood so that the tree can regenerate. “If you let it drain on its own, the tree dies. But if you seal it, in three or four months it starts producing oil again.”

Just as Raimundo extracts copaíba oil, Edmilson, who identifies as Indigenous, is dedicated to harvesting buriti, the fruit of a palm native to the Amazon and Cerrado biomes. This palm can reach over thirty metres in height and grows in flooded areas or near rivers and streams, forming what are known as buritizais (buriti groves). Edmilson has observed an acceleration in deforestation over the past twenty years. During our time together, he speaks of the pain he feels watching the forest disappear, because along with it disappears their way of life in the forest. He feels himself to be part of the forest: when he hears the song of a bird or drinks clean water, it fills him with strength. As part of the forest, he knows everything that inhabits it: mutum, jacu, jacamim, azulona, nambu, jaguars, monkeys, wild pigs, tapirs. And when it comes to the plants found there, there are countless medicinal ones, plants capable of miracles.

Edmilson’s father worked on the construction of the Transamazonian highway between 1972 and 1973. During the construction, teams of twenty people were organized: while some cleared the land, others opened the road. Many people fell ill and died during the process. At that time, the area had few inhabitants, but today there is not a square metre of land without an owner. Much of the land has since been abandoned, but still there remain those, like Edmilson, who continue to live in the territory.

At the end of the journey, in weaving together the accounts and experiences that make up the social system of Apuí, we came to understand that the design of the Agroforestry Centre and Forest Observatory is at once an architectural project and a landscape project. More than that, it is an exercise in revisiting preconceived assumptions and conventional definitions of what it means to “build” a forest. The foundation of this process lies not only in techniques but in the social, ideological, and political work that underpins every act of planting, preserving, and resisting.

To ignore the historical, social, and political dimensions that have shaped the current state of this land would be to remain at surface level; to bring them to light, however, opens space for the invention of new ideas, architectures, and territories. How can architecture, among many other systems of knowledge and representation, produce nature, within and beyond its own disciplinary field? This question becomes central in the experience of Apuí. From a methodological perspective, it implies revisiting the different forms of codification, representation, cartography, archiving, and institutionalization of knowledge that architecture itself generates.

Through the journey, we understood that to observe is not merely to record, but to learn with people, their practices, their memories, and their ways of imagining the future. In this sense, the Agroforestry Centre and Forest Observatory is not only a project to be designed, but a living territory under construction, made of voices, knowledges, and resistances that continue to reinvent the forest.