An Architect Who Works With Citizens

Kozo Kadowaki on the Shonandai Cultural Centre by Itsuko Hasegawa

A hypothesis about Itsuko Hasegawa

As an architect, Itsuko Hasegawa has continually resisted conventional powers and authorities, always working with ordinary people in mind. We can observe this stance and commitment in her design process for the Shonandai Cultural Centre, a project completed in 1990. Throughout that process, Hasegawa interacted tirelessly with the local public, an unusual approach in those days. Today, this fact is drawing renewed attention, as citizen participation in public architecture is increasingly the norm.1 It should also be noted that the Shonandai Cultural Centre, arguably Hasegawa’s defining masterpiece and the one that cemented her standing as an architect, was designed and built at the height of an economic bubble in Japan, when the economy grew at an abnormal rate—yet Hasegawa never allowed herself to be swayed by the marketplace nor by populist impulses.

-

For a recent article discussing the design process for the Shonandai Cultural Centre, see Itsuko Hasegawa (in conversation), “The Design Process for Shonandai Cultural Centre (1990): When Authoritarianism Began to Collapse,” Journal of Architecture and Building Science, vol. 133, no. 1707: 3–6. ↩

It is difficult to assess the precise effect of an event that took place in such a turbulent era but, on the other hand, over three decades have passed. Therefore, I would like to advance a certain hypothesis about her work—that the Shonandai Cultural Centre represents the manifestation in public architecture of the culmination of diverse experiments in Japanese housing conducted in the 1970s. The experimental character of small residences in Japan is known throughout the world, but the link between those projects and Japan’s public buildings, a genre that differs from housing not only in scale but other aspects as well, remains largely unexplored. How, then, did experimentation with small residences find its maturity in public architecture?

Exploration of this hypothesis required the study of material from this period as well as a conversation with Hasegawa herself. This process toward understanding the circumstances surrounding the paradoxical relationship between small houses and public buildings led me to reevaluate the vibrancy of Japanese architecture of the 1980s, precisely in the midst of the postmodernist era. A bit of background is needed, however, if we are to make sense of the details of this relationship.

The shock (and consumption) of the Shonandai Cultural Centre

Hasegawa is part of a group of architects born in the early 1940s who were dubbed “wandering samurai in an era of peace” by Fumihiko Maki. His description, which referenced the Akira Kurosawa film Seven Samurai, appeared when Hasegawa and her contemporaries were still young. In an essay published in the October 1979 issue of Shinkenchiku magazine,1 Kurosawa’s protagonists were masterless itinerant samurai hired by peasants to fight on their behalf. Maki saw something of these freelance warriors in young architects whose passion for architecture spurred them to make art out of utterly conventional residences for ordinary citizens.

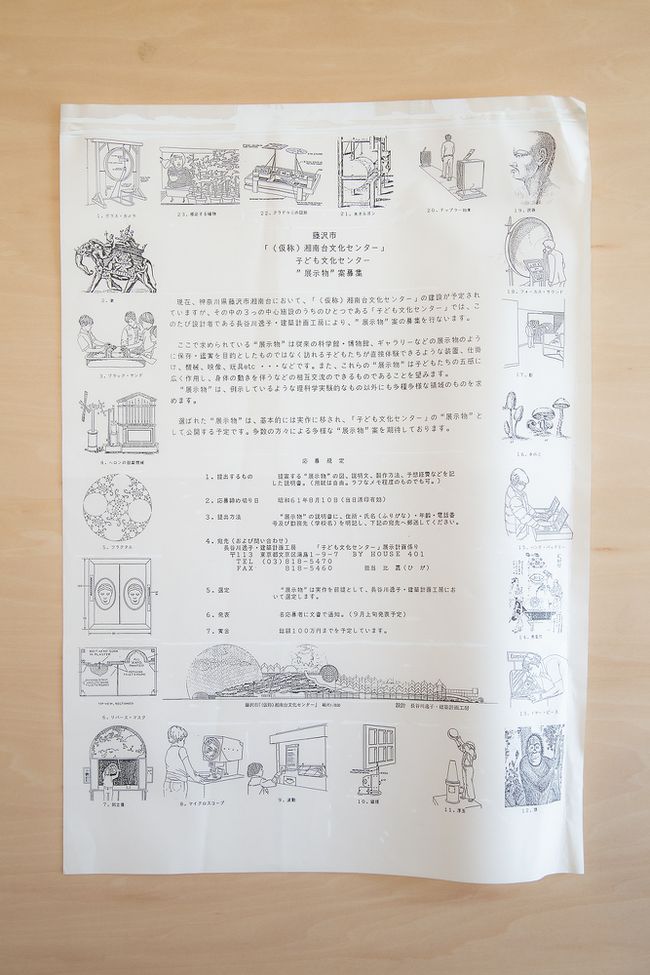

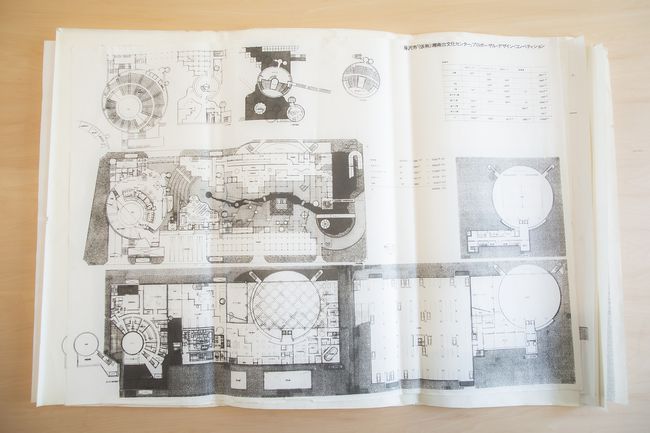

In 1986, one of these young architects, Hasegawa, underwent a precipitous rise to stardom. That year, she won the Architectural Institute of Japan Prize, considered the country’s most prestigious architectural award, for Bizan Hall, a project completed the previous year. At around the same time, she also won the competition to design a cultural centre at Shonandai in the city of Fujisawa, besting over a thousand other contestants and 215 submitted designs. These concurrent feats not only made her an instant architectural celebrity but also signified the arrival of women among the top ranks of Japanese architects.2

-

Fumihiko Maki, “Wandering Samurai in an Era of Peace,” Shinkenchiku, October 1979 issue: 195–206. ↩

-

Architect Akiyoshi Hirayama, for example, saw the results of the competition as an indication that “this era will inevitably belong to women.” Akiyoshi Hirayama, “Monthly Review,” Shinkenchiku, May 1986 issue: 290–291. ↩

Hasegawa’s proposal for the competition was technologically innovative, prompting concerns about a laborious design process and high construction costs that were voiced from the moment the project was announced until its completion.1 However, Hasegawa surmounted these and many other challenges to finish the Shonandai Cultural Centre in 1990. Not only did the final structure silence its naysayers, it also expressed a vision of a hi-tech community of the future even more forcefully than it had in its initial design.

The Shonandai Cultural Centre came as a shock. It was received as the product of an entirely new architectural approach that abandoned the established, conventional formalism for something chaotic yet light and ephemeral. But, with its completion coinciding with the peak of Japan’s economic bubble, the Centre was cursed with unfortunate timing. When the bubble burst and the country entered a prolonged period of economic stagnation, the structure came to be viewed by many as a frivolous work borne of the excesses of its time. In reality, the Centre was a relatively low-cost project with a budget based on pre-bubble unit construction costs. Hasegawa won the competition in April 1986, and the bubble is said to have begun expanding in December that year.

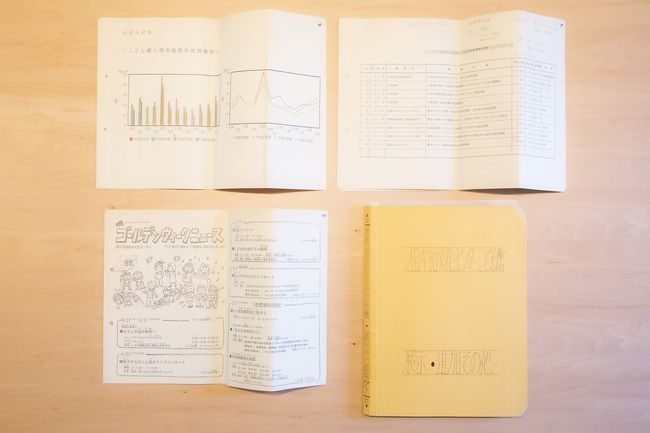

Unfortunately, misconceptions of this sort have a way of thriving. I recall that when I entered university in the late 1990s, the Shonandai Cultural Centre had already lost its sheen of novelty and was perceived as a vestige of a bygone era. The competition result had enjoyed widespread publicity, and architectural journals and other media had reported on the development of its design.2 But precisely because of the attention it had received, similar works inspired by Hasegawa’s proposal began to appear even before the structure was finished,3 no doubt accelerating the speed with which the building’s symbolic value was consumed by the architectural milieu.

-

Teiichi Takahashi, “Monthly Review,” Shinkenchiku, May 1986 issue: 289. ↩

-

Itsuko Hasegawa, “Working Drawings Proposal for Shonandai Cultural Centre,” Shinkenchiku, September 1987 issue: 183–186. ↩

-

As attested by architect Katsuhiro Kobayashi in his “Monthly Review,” Shinkenchiku, October 1989 issue: 325–326. ↩

The small house experiment

Why did Hasegawa and her fellow “wandering samurai” begin to engage with small residences in late-1970s Japan in the first place? To answer this question, we need to take a brief look at the history of contemporary architecture in Japan.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Japanese architects began addressing the urgent need to revive cities and livelihoods that had been destroyed. To this end, they had to quickly supply a vast number of urban buildings and dwellings, which they accomplished through a large-scale rationalization of engineering-based designs and the industrialization of architectural production. This process, which was overseen by bureaucratic bodies, enlisted architects and technocrats in the realization of a radically progressivist urban-architectural vision that bordered on the utopian. It was a vision that found its most concrete expression in the Japan World Exposition, also known as Expo ’70, held in Osaka in 1970 under the theme “Progress and Harmony for Mankind.”

During this same time, a rebellion against modernism was occurring in various forms around the world. The Paris Revolution of May 1968 made its influence felt in places like Milan and Venice, where students and young artists occupied the sites of the Milan Triennale and Venice Biennale. Young architects in Europe launched an avant-garde architectural movement that resonated with these developments, and Arata Isozaki took the lead in introducing its central figures to Japan through a series of columns he began writing for the art journal Bijutsu Techo in late 1969.1 Though Expo ’70 the following year marked the zenith of modernism in Japanese architecture, it could not counter the trends of the times. Progressive modernism declined soon thereafter in Japan, compelling architects to search for an alternative approach to design.

The architects who responded most swiftly to the collapse of modernism were the “wandering samurai” of the generation following Isozaki’s. Maki had applied the moniker to architects like Hasegawa, Osamu Ishiyama, Tadao Ando, and Toyo Ito who shared a determination to devise a contemporary architecture “for the people,” independent of bureaucracies and other forces of authority. The 1970s saw a flowering of diversely radical experiments—there is even a book whose title refers to these efforts as a “crazy blooming”2—by these young architects who primarily took on small residences as their medium. The upshot is that many Japanese houses designed in the 1970s posed fundamental questions about society that still resonate today. I would like to enumerate some of the most significant statements they make here.

First, through their designs of small residences, young architects of this period exhibited an unambiguous rejection of the frenetic pace of urbanization and its subsequent degradation of the natural environment. As can be seen in works like Tadao Ando’s early-career project Row House in Sumiyoshi (1977), the exteriors of their urban residences appear closed-off. Such designs represent a conscious rejection of the city,3 but not a simplistic aversion to the urban as something to abandon outright. Even as they reject the current state of the city, these small residences are built in its midst—in other words, these projects articulate a new approach to confronting the urban environment.

Second, these young architects did not hesitate to address the industrialization of architectural production that contributed to the huge volume of construction behind this urban sprawl. Architects of the 1970s were compelled to develop a logic for working with industrialized building materials that were coming into widespread use for the first time, and small residences served as a testing ground. Osamu Ishiyama, one of the architects who took this challenge head-on, created a series of residences that utilized corrugated metal pipe, exemplified by his 1975 Gen-An (Fantasy Villa). These were houses that used industrialized materials and building methods in service of a noble and sincere vision of living spaces in which people could dwell with dignity and autonomy. Efforts like Ishiyama’s during this period cleared an unimagined path for architectural production.

Third, these “wandering samurai” encouraged the active engagement of people with the spaces they inhabited. In houses like Gen-An, Ishiyama treated industrialized building methods as a technology for residents themselves to utilize, facilitating through his designs their participation in the construction process. This was also an era that saw numerous small residences designed and built by architects for their own use, such as Isamu Kujirai’s Poulailler (1973) and Eiji Yamane’s Crow Castle (1972). These houses are designed to allow the residents to keep modifying them after their initial completion, well beyond the original architectural plans. In this regard, these projects can be viewed as experiments in handing the reins of control over architecture from the builder to the user.

At some point in the 1980s, however, Japanese architecture began to lose its way. With the advent of a full-fledged consumer society came a proliferation of architecture that pandered to capitalist and populist trends. The growth of the economic bubble only exacerbated this tendency. It was the very heyday of postmodern architecture, and Japan, too, was subject to indiscriminate displays of symbolic elements derived from Western architecture that displayed no continuity with the country’s own history. Frivolity ruled the day and then just as quickly vanished when the bubble burst. The Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995, followed in short order by the Tokyo Sarin terrorism events, dealt the final blow to the euphoria of the bubble years. The ornamental excesses of architecture from that period became an object of ridicule and, by the late 1990s, Japanese architects had made a hard turn toward minimalism.

-

Isozaki’s columns, which continued until 1973, were compiled in the book Dissecting Architecture: The State of Architecture in 1968 (Bijutsu Shuppan-Sha, 1975) and would have an impact for years to come. ↩

-

X-Knowledge (ed.), Housing of the Seventies: A Crazy Blooming (X-Knowledge, 2006). ↩

-

Ando writes, in a 1973 essay, that it is imperative to “eliminate the façade, so as to express aversion to and rejection of the external environment.” Tadao Ando, “Urban Guerilla House” Toshi Jutaku, July 1973 issue: 18–19. ↩

Not a disruption, but continuity and expansion

In my view, the Shonandai Cultural Centre is a work that has suffered a diminution of significance due to the circumstances I have described above. To investigate my hypothesis that the project manifests, through public architecture, a fruition of experiments in small housing, I studied documents in the public domain as well as materials kept at Hasegawa’s office. From this research I conclude that the Centre is distinguished by the following attributes:

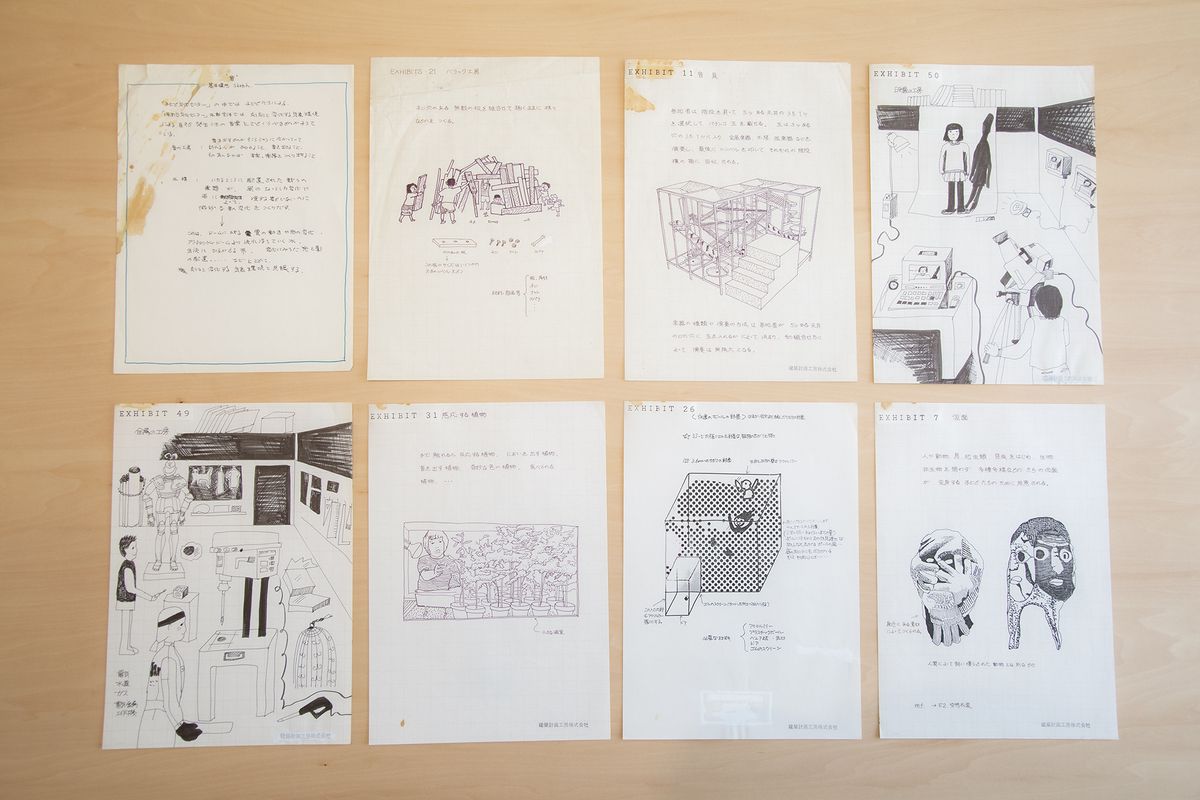

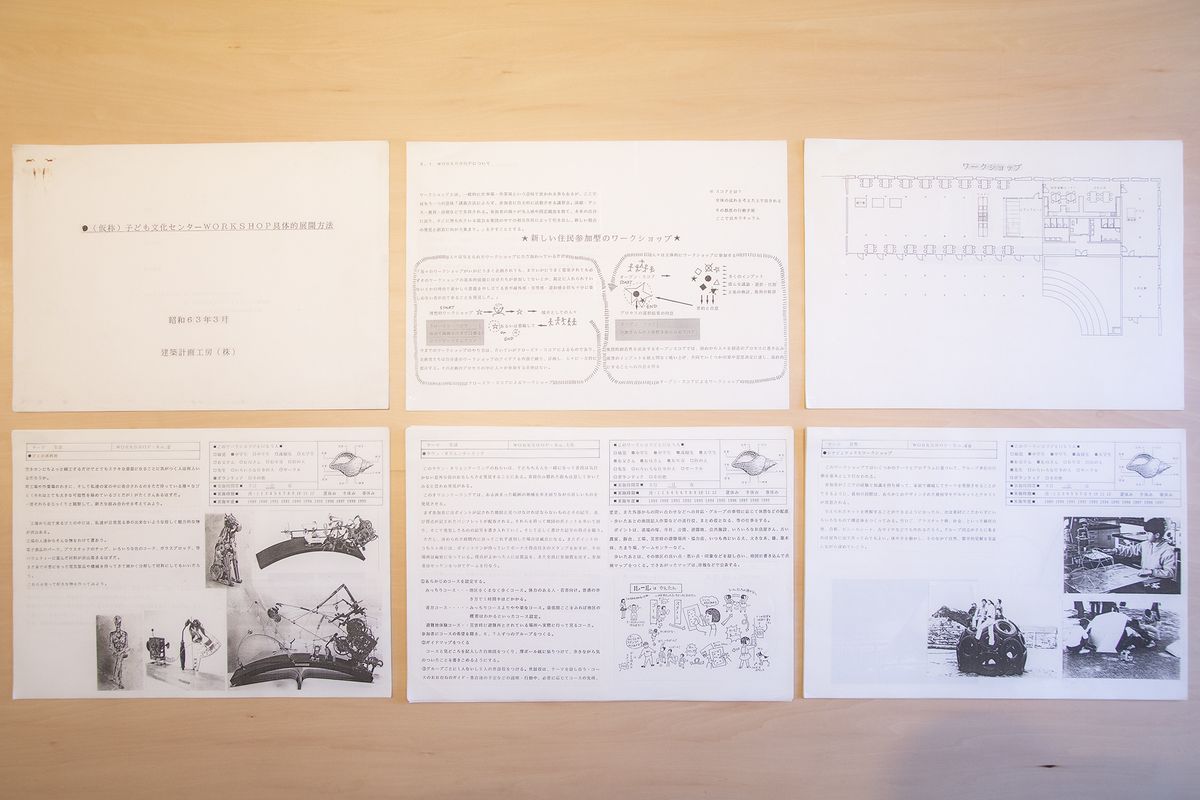

1) Hasegawa developed the Shonandai Cultural Centre in consultation with local citizens. During the design process, she engaged in innovative practices such as encouraging citizen participation through open meetings with the general public. In this way, she demonstrated that she was an “architect who works with citizens” (i.e., the architect as a partner) rather than an “architect who enlightens citizens” (i.e., the architect as an authority).

2) Hasegawa made a bold commitment to the Centre’s operations. The Centre was a rare example in its time of a public facility for which the architect was involved in planning its management from the outset. This laid the groundwork for the Hasegawa office’s establishment of a methodology for subsequent engagements with the Centre’s public programs.

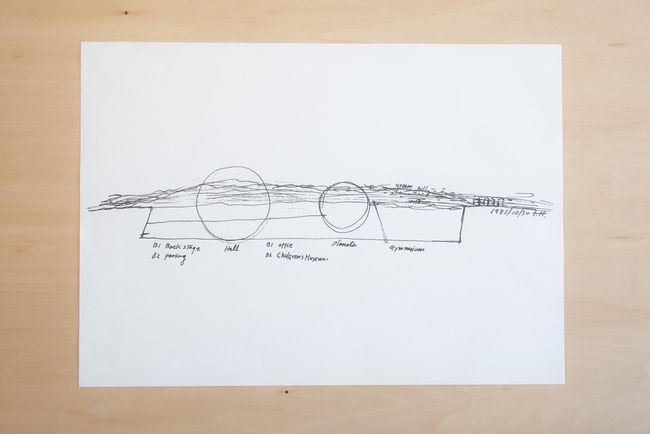

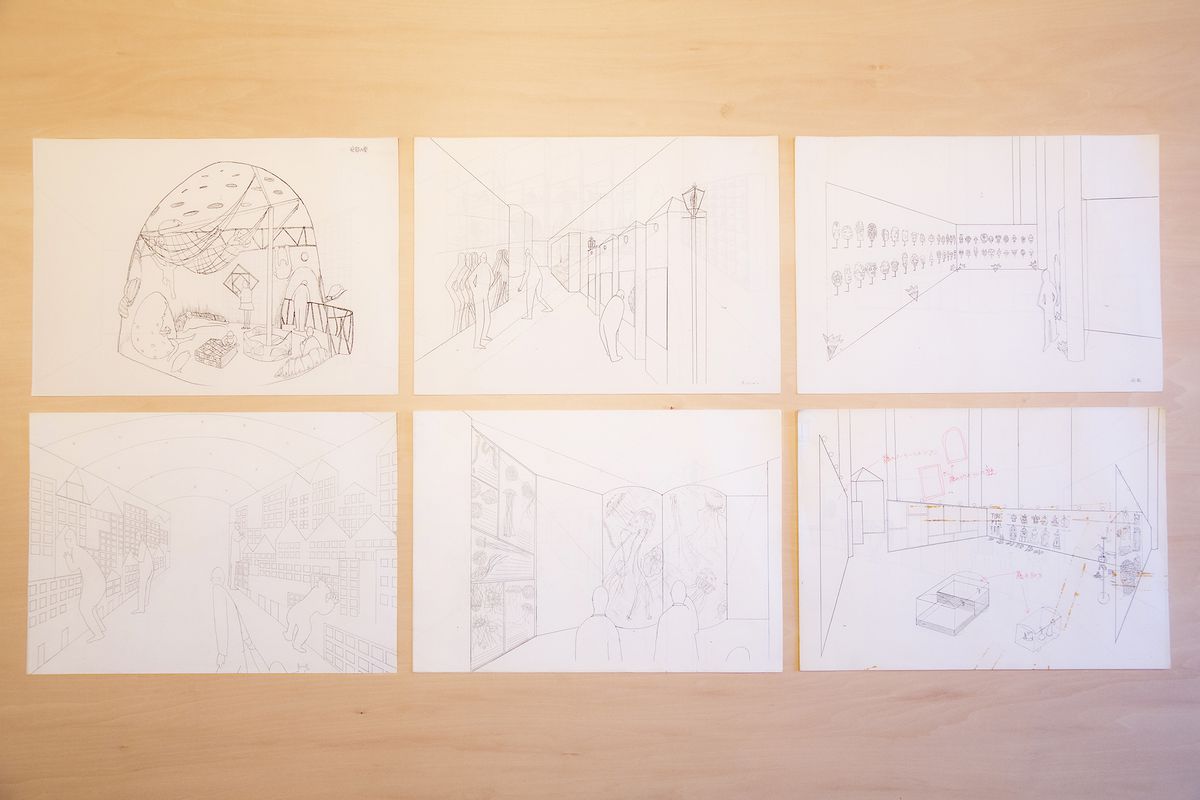

3) Hasegawa initiated a collective approach to the production of elements. She has used the phrase “architecture as a second kind of nature” to describe the Shonandai Cultural Centre. Working from this concept on a platform consisting of an artificial slab, she laid out diverse elements that defy definition as either architecture or furnishings. Just like flowers blooming, their arrangement was in a way entirely ad hoc. These elements utilized materials ranging from new to traditional, from perforated metal to tile, with a sizable number produced by architectural designers, artists, students and other participants for the immediate purpose of minimizing costs. This design not only signifies ephemerality but can be understood as the result of a collective production process that attained a harmonious whole through the creativity of multiple participants.

4) Hasegawa engaged with the production system. The late 1980s were a time when industrial parts and industrialized construction methods had become widespread, and the architectural production system was on the verge of full industrialization. The Shonandai Cultural Centre, however, contained a mix of hand-worked elements introduced via the participation of architectural designers and craftsmen in the production process. The Centre also employed a variety of newly developed technologies, such as a thermal spray aluminum used for the dome. Thus, Hasegawa actively inserted herself into the architectural production system. In this respect, Hasegawa distinguished herself from later architects who found themselves alienated by the rapid advancements of that same system.

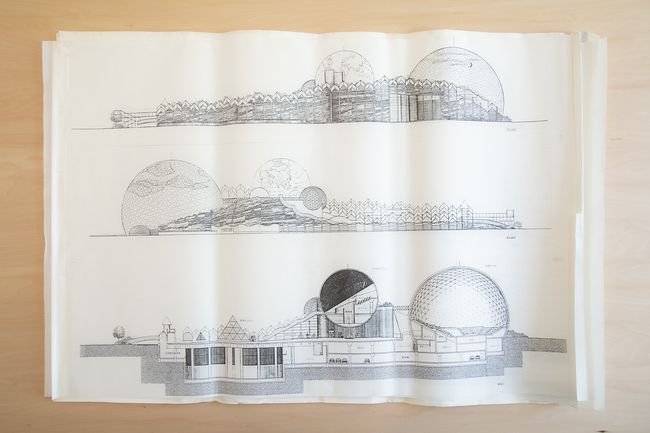

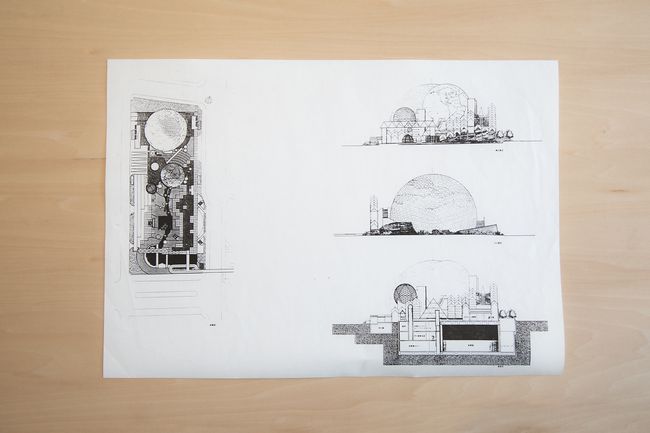

Itsuko Hasegawa, long elevations and section for the Shonandai Cultural Centre competition, 1985. Photograph by Kohei Omachi, 2020. © Itsuko Hasegawa Atelier

5) Hasegawa introduced a new discourse to the architectural field. The Shonandai Cultural Centre heralded the participation of women at all scales and in all areas of Japan’s architectural milieu, which until then had been an exclusively male, discourse. The Centre was groundbreaking in its introduction of a new discourse concerning gender.

The above attributes can be said to have roots in the soil collectively cultivated by Hasegawa and her contemporaries through their work on small residences in the 1970s. Every one of these attributes can also be viewed as a sharply critical challenge to contemporary architectural circles.

As a central figure in the “wandering samurai” coterie of architects, Hasegawa, by her own admission, engaged in frequent and vigorous debates with her contemporaries, both in public and in private.1 Even in her relatively small-scale works preceding the Shonandai Cultural Centre, we can see clear evidence of a confrontational stance vis-à-vis the industrialized technologies that contributed to urban gigantism and environmental degradation, as well as a commitment to yielding power over architecture to residents and users—attitudes reflected in the small houses of the 1970s as well.

For the Tokumaru Children’s Clinic (1979), for example, she took pains to cultivate an equitable architect-client relationship, eschewing arbitrary decisions by the architect. For her Aono Building (1982), she supported the active post-completion utilization and smooth management by users by including them in the planning process. For House at Kuwahara (1980), she pioneered the artistic use of new materials such as perforated metal, launching a trend that would become ubiquitous in Japanese architecture and arguably contributing a more nuanced sensibility to the industrialized cityscape. Shonandai Cultural Centre is thus an extension of Hasegawa’s work up to that point, and the antithetical stance it represents is clearly linked to the 1970s.

A critical understanding of this historical moment is underdeveloped in Japanese architecture, and this implicitly demands a reassessment of postmodern architecture in Japan. The road taken by contemporary architecture in Japan since the 1990s appears to have arrived at an impasse, particularly in the wake of the earthquake and tsunami disaster of 2011. Perhaps the way forward can be retroactively found in the daring architectural experiments born of the frenetic boom years of 1980s Japan.

-

Based on Hasegawa’s own words in Itsuko Hasegawa, Koh Kitayama, and Go Hasegawa, “A New Age of Discovery,” TOTO Tsushin, Summer 2013 issue: 4–13. ↩

Translation from the original Japanese to English provided by Alan Gleason.

This essay is part of Meanwhile in Japan, a CCA c/o Tokyo project that includes three events in Tokyo, four web essays, and three forthcoming books.

Related articles