Bridging a Chasm

Koji Ichikawa on Toyo Ito’s Commodified Housing Study Group

I. Things overlooked

Recipient of the 2013 Pritzker Architecture Prize, Toyo Ito is known both in Japan and abroad as one of the country’s leading architects from the last few decades of the twentieth century to the present day. An overview of Ito’s career reveals some distinguishing traits.

Ito was born in 1941 in Gyeongseong (now Seoul), Korea, while it was under Japanese occupation, and his family soon moved back to Nagano Prefecture, Japan, the home of Ito’s grandfather. As he began middle school, Ito moved to Tokyo and then, while studying at the University of Tokyo, he started working for Kiyonori Kikutake, a central figure of the Metabolist movement. Ito continued to work with Kikutake before opening his own architectural office in 1971. Thus since adolescence, he has made his base in Tokyo, though his projects have locations throughout Japan and the world at large.

Ito’s oeuvre includes White U (1976) and Silver Hut (1984), two canonical projects of experimental residential architecture in Japan; Sendai Mediatheque (2000), winner of a design competition for which Arata Isozaki was head juror; Home for All (2011–present), a project that builds community spaces in areas devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011; and Taiwan’s National Taichung Theatre (2016), noted for its curved surfaces. Superficially, these works appear vastly disparate in style—but in my view, it is this very diversity and versatility that epitomizes Ito’s career.

For the Meanwhile in Japan research project on the development of postmodern architecture in Japan, our inquiry into Ito’s work focuses upon a practice, one of the many that make up his oeuvre, that attracts little if any attention today: the Commodified Housing Study Group. Ito hosted this group with Yoshiro Sofue, Kazuyo Sejima, and others on his staff during the early 1980s, when his office was still small and relatively unknown. Their subject of study was commodified housing, a new type of product that had made its debut on the Japanese housing market in the 1970s.

Why did we choose to focus on this study group, which at first glance was a low-priority activity? The reason is simple: its concerns directly addressed the social stance and role of architects in postwar Japan, a time and space considered uniquely significant by Western observers.

The profession of architect made its first appearance in Japan at the end of the nineteenth century as a critical component of the construction industry under the Meiji state, which was determined to modernize Japan as rapidly as possible. However, during the Second World War and the economic boom years that followed, architects found themselves gradually marginalized. Ito’s Commodified Housing Study Group can be viewed as a practice of criticism and resistance vis-à-vis this trend. This practice is not a thing of the past but remains relevant to this day, as evidenced by the fierce debate that continues in Japan’s architectural milieu over the role of the architect in society and the social utility of architecture—part of a general effort to liberate the profession from a certain sense of societal alienation experienced by architects in the country.

II. A golden age that bore no fruit?

To understand the significance of Ito’s Commodified Housing Study Group in the early 1980s, we must first review the relationship between architects and Japan’s postwar housing industry.

When the Second World War finally ended in August 1945, Japan faced a severe housing shortage, lacking as many as 4.2 million houses. The task at hand was to modernize the nation’s housing stock and efficiently produce enough new housing for the population. Housing production had to be industrialized, and it became a matter of national urgency and among the most critical tasks facing architects of the day. An example of a response was the PREMOS prototype for a prefabricated house made of wooden panels, designed by architect Kunio Maekawa in concert with an engineer and an aircraft factory.

From the 1960s on, however, architects experimented less. In their place, prefab housing manufacturers rose to prominence, eventually coming to dominate the Japanese housing industry. During the 1960s and 1970s, Japan enjoyed a period of miraculous, rapid economic growth accompanied by societal changes that inevitably fomented an equally dramatic shift in the expectations and desires of citizens in regards to housing. The industrialization of housing during the early postwar years made it possible for many to purchase inexpensive high-quality homes in the wake of mass-produced housing materials, but this also encouraged clients to demand that home builders offer special designs and ornamentation, as well as models for attractive lifestyles. Houses evolved from industrial products into customizable consumer goods. For example, fireplaces and dormer windows became popular as trendy symbols of a Western lifestyle.

It was during the 1970s that housing in Japan made this transition from an industrialized mode of production to a commercialized one. If industrialized housing could be described as the result of modernist aspirations to provide efficiently mass-produced architecture, then commodified housing arose from a postmodernist aspiration to provide architecture that responded to the desires of a mass-consumer society. Our research project is concerned with this moment and the prevailing thought that the architects most prominently featured in the nation’s architectural media at the time for the most part expressed no commitment to addressing the fundamental changes occurring within the housing market of the 1970s. Far from engaging with the needs of the housing industry during this period—as architects like Maekawa had in the immediate postwar era—these architects immersed themselves in experiments with architectural forms and spaces driven by the concerns of their own personal practices.

Emblematic of this trend was the generation of architects who came to be dubbed the nobushi, or “wandering samurai.” This was the appellation given by Fumihiko Maki to a number of young architects who emerged in the 1970s, among them Tadao Ando, Osamu Ishiyama, and Toyo Ito.1 Without patrons or mentors, relying solely on their own talents for survival, these mavericks were likened to the masterless samurai of Japan’s premodern era. Underlying works like Ando’s Row House in Sumiyoshi, Ishiyama’s Gen-An (Fantasy Villa), and Ito’s White U was a conscious rejection of urban context and the systematized housing industry. These projects were also outcomes of highly original methodologies of design, applied to houses constructed from unique materials yielding rich spaces within the closed confines of home interiors. A similar inclination can be seen in the work of some architects of an older generation such as Kazuo Shinohara, who declared that “a house is a work of art,”2 or Isozaki, who spoke of “withdrawal from the city.”3

In the case of the nobushi architects, however, this stance was not something they actively accepted so much as one that was thrust upon them. An earlier generation of architects, including Isozaki and Kenzo Tange, enjoyed opportunities to design and plan urban and public structures from a young age. But by the time the nobushi debuted in the 1970s, urban development and the industrialization of housing were well underway, leaving little for them to work on apart from small private dwellings and a few commercial facilities. Consigned to fighting their battles on the margins of society, the nobushi had no choice but to devise their own kind of architecture.

The upshot was that, in the 1970s, Japan became a laboratory for residential architecture unlike any other the world has seen. Architects who would become globally recognized figures in the field seemed to vie with one another in regaling the mass media with idiosyncratic housing designs. The players included not only Ando, of Row House in Sumiyoshi fame, and Ito, with his White U, but also Shinohara, Hiroshi Hara, Kazunari Sakamoto, and Itsuko Hasegawa.

Referring to the 1970s as Japan’s “golden age of housing,” architect and Tokyo Institute of Technology professor Shin-ichi Okuyama cited as its attributes “formalism” and an “introversion” of space in the quest for a “form and organizational methodology for architecture itself” as well as a rich, experimental practice made possible by these elements.4 Housing in the 1970s can thus be characterized by an intentional severing of its relationship to its social and urban contexts and by a tireless exploration of form and space in the residential architecture that resulted.

-

Fumihiko Maki, “Wandering Samurai in an Era of Peace” (Shinkenchiku, October 1979) ↩

-

Kazuo Shinohara, Juutakuron [Discourse on Housing] (Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing, 1970) ↩

-

While Isozaki himself never spoke of a “withdrawal from the city,” he has noted that others use the phrase to describe his attitude toward the city around the 1960s and 70s. ↩

-

Shin-ichi Okuyama, “Formalism, the Design of Introverted ‘Boxes,’ and the 1970s” (Shinkenchiku Special Issue: The Trajectory of Contemporary Architecture, December 1995) ↩

However, we must also note that this “golden age” of experimental housing was an extremely marginal phenomenon that occurred on the fringes of, or even entirely apart from, the urban development and industrialized housing projects that typified Japan construction during its economic boom years and persisted for some time despite two oil-shock crises. Shoji Hayashi, known as the leading architect at Nikken Sekkei, postwar Japan’s largest architecture design office, evaluated the nobushi phenomenon within this framework. To Hayashi, the experimental residential architecture of the nobushi was no more than “the vain blooming of a pretty but fruitless flower.”1 In his view, such experiments were of architectural interest but had no substantial meaning—in other words, they bore no fruit—for Japanese cities and society at large.

-

Shoji Hayashi, “An Era of Distorted Architecture: Looking Back on the 1970s” (Shinkenchiku, December 1979) ↩

III. Why study commodified housing?

Such was the context within which Ito launched the Commodified Housing Study Group (hereafter, the Study Group) in the early 1980s. Why, then, did the group choose to study commodified housing, and how did it go about it?

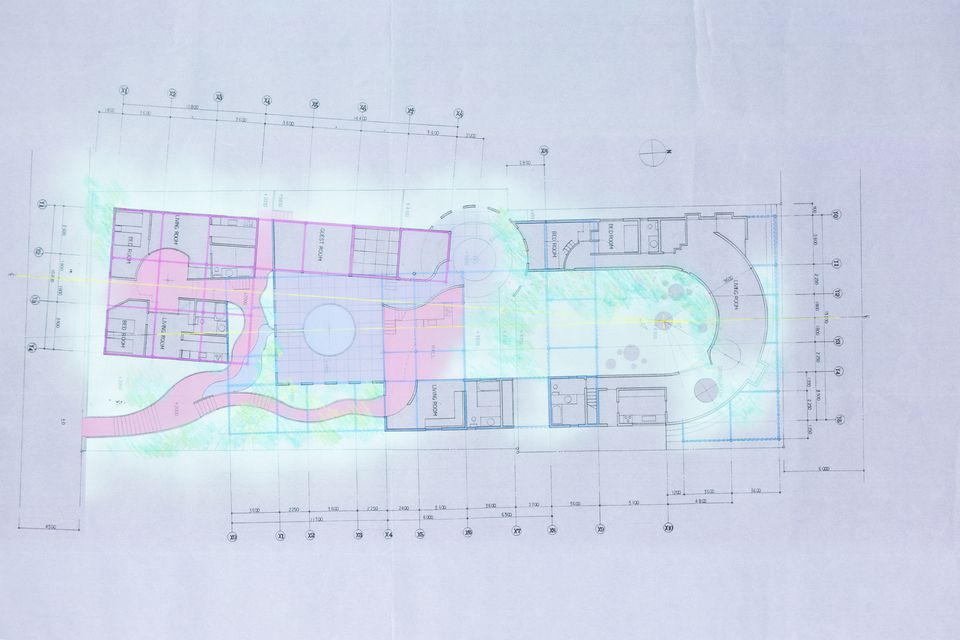

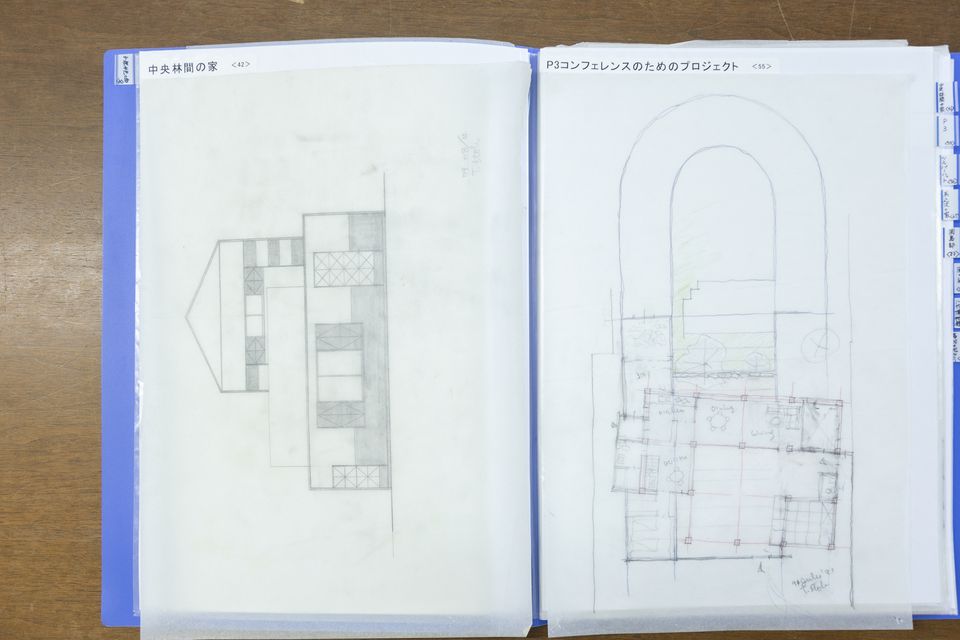

To pursue these questions, we conducted the following research: we surveyed documents of the Study Group preserved at Ito’s office along with works of housing design from preceding and following years; we surveyed Ito’s writings from the 1970s and 1980s; we interviewed Ito; and we interviewed Ito again, joined by a small audience.

From these various sources we learned that the Study Group was active for about three years, from 1981 through 1983. Though its schedule was irregular, at its most frequent the group convened at Ito’s office on a weekly basis. Among those named as members were Ito, several staffers including Sofue and Sejima, and, initially, an employee of Panasonic Homes, a major commercial home builder.

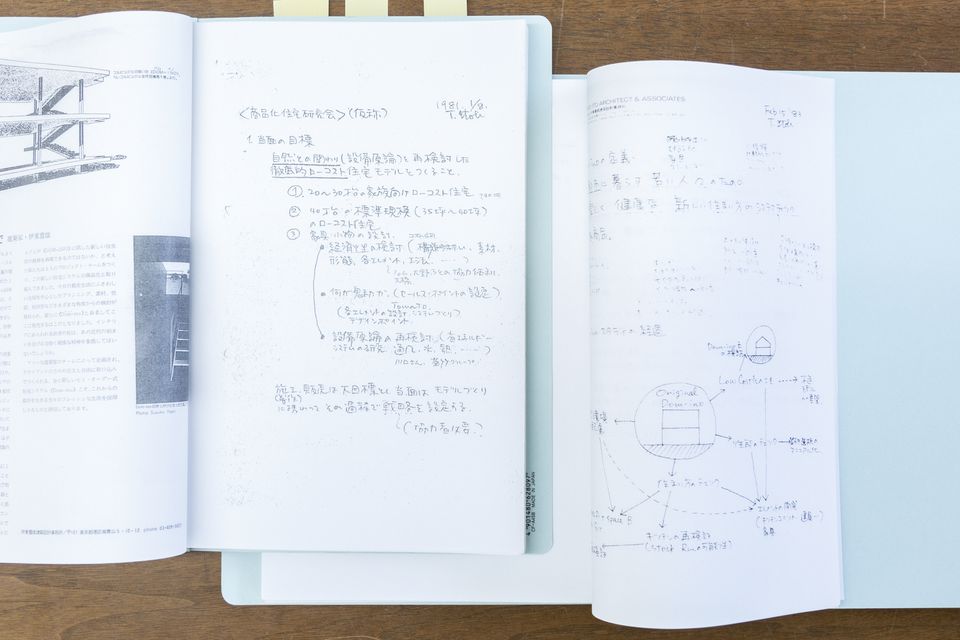

The materials stored at the office include a handwritten manifesto, probably by Ito, titled “Objectives of the Launch of the Study Group” and dated January 1981, when the group was first convened. It contains the following statement:

We are launching this study group for the purpose of carrying out surveys and research with the objective of creating housing as a new type of consumer product that is neither the “work of an architect” nor like conventional built-for-sale or prefabricated housing. 1

This is a short but intriguing text. Reading it against the backdrop described above gives us a ready understanding of Ito’s concerns at the time. In brief, after architects became estranged from the housing industry in the 1970s, he sought to mend the relationship. Such was his motivation for starting the Study Group.

-

Underlining by the author. ↩

An “Objectives of the Launch” document follows this opening manifesto with a list of specific objectives and tasks. The listed objectives are to: ensure economic feasibility; control the natural environment; and accommodate new lifestyles. The tasks are to: gather information; create model images; and prepare a manual. Based on these guidelines, the Study Group examined criteria such as thermal performance and price range in case studies of commercial housing then on the market; studied the use of conventional Japanese wood-frame, two-by-four, and steel-frame construction methods; interviewed a sampling of the young urban residents who formed the main consumer demographic of Japan’s housing market; and developed new models for commercial housing.

Of the recorded activities of the Study Group, actual commodified housing prototypes designed by the group caught our eyes. What is of special interest is that the group did not limit itself to an in-house study. After considering two-by-four and steel-frame models, the group settled on the latter, and then actively sought clients for their designs through a feature in the 10 October 1981 issue of Croissant, a lifestyle magazine that targeted a sophisticated urban female readership.

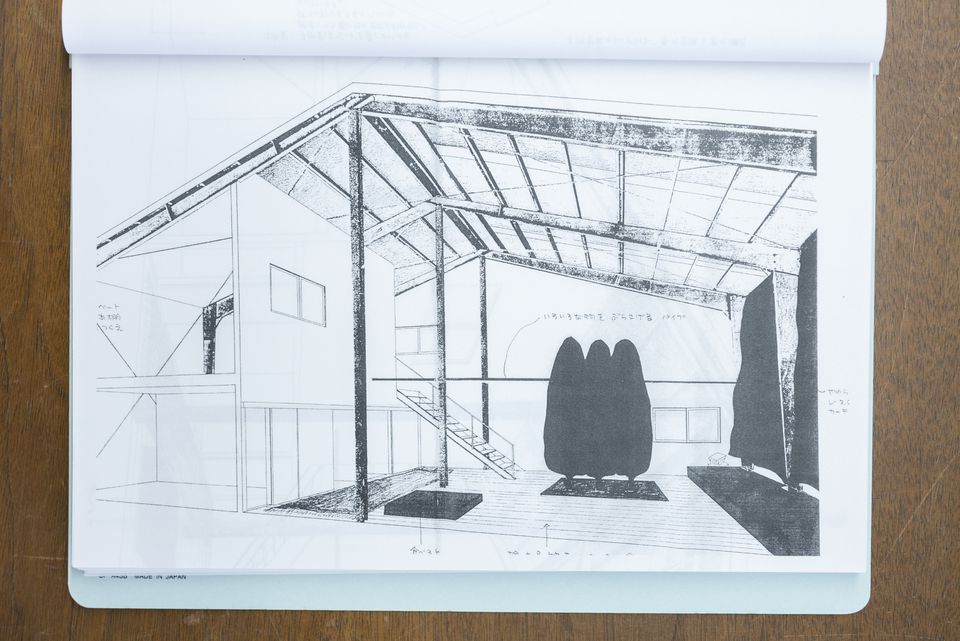

Titled “Semi-Customized Houses That Look Different for Each Resident,” the article uses an axonometric illustration to showcase house interiors. The presentation is clearly aimed at attracting the interest of ordinary readers, not just architecture professionals. The overall style is very Pop and quite unlike that of articles in architectural journals, which typically consist of various design drawings, photographs of the finished structure devoid of human presence, and abstruse texts by architects.

The Croissant article introduces two steel-frame prototypes: “House with a Second-floor Living Room” and “House with a Doma.” Both are catchy names typical of those given to commercial houses of the day, and were probably inspired by the case studies conducted by the Study Group. The houses are simple box structures lacking any standout features in their overall design or plan. But in features like the doma, a traditionally earthen-floored space that takes up much of the ground floor and accommodates all manner of uses, blurring the boundary between interior and exterior, one can see harbingers of the spatial schemes found in subsequent works by Ito like Silver Hut. Meanwhile, a flamingo that appears in an axonometric drawing of a first-floor bedroom might be viewed as a symbolic expression of this conscious attempt at commercial appeal. The flamingo was also the icon of pop musician Christopher Cross, who enjoyed a following in Japan in the 1980s.

After the publication of the article in Croissant, Ito’s office apparently received inquiries from several potential clients, yet most of these communications did no more than relay people’s impressions of the houses and did not lead to actual commissions. Ultimately, the only project that resulted directly from the Study Group’s media campaign was House in Umegaoka, completed in 1982. Commissioned by the video artist Sakumi Hagiwara, the house had a plain, simple steel-framed box structure modeled after the prototypes so appealingly presented in the magazine.

Everything about this work, including the impression it made of a bright, airy space, was a complete departure from Ito’s works of the 1970s, such as Aluminum House (1971), which resembled a pair of chimneys, and the U-shaped White U. Among Ito’s works, two that are often singled out for their differences are the heavily introverted White U and the light, open Silver Hut. House in Umegaoka, between these two projects, displays the first hints of a shift in style.

IV. A hopelessly deep chasm

In the two interviews we conducted for Meanwhile in Japan, we were particularly struck by Ito’s own perception of the Study Group. In short, he gives a surprisingly low assessment, exemplified by responses such as “I don’t really remember…it was not such a serious undertaking. I only did it because I was out of work and had time on my hands…” Repeatedly replying to our detailed queries with negative recollections of this sort, Ito seemed to be trying to deflate our interest in this study group that lasted only a few years.

The ambitious tone of the 1981 manifesto notwithstanding, Ito today seems to view the Study Group as a failed project. One reason that comes to mind is that the Croissant feature did not generate the hoped-for response. Japan’s architecture-related media were at the peak of their influence in the 1970s and 1980s. Ito and his associates willfully turned their backs on them, instead promoting their work in a fashionable women’s general-interest magazine—in the end, they were able to build only one house according to their prototype. It is not hard to imagine their frustration at failing to elicit a favourable reaction from the ranks of potential house buyers.

Ito’s career as an architect also suggests some idea as to why he perceives the project as a failure. Ever since his debut in the early 1970s, he has concerned himself with the relations between architecture and society, and between architect and client or user—or rather, with the fissures in those relations. Indeed, he was already articulating this concern at the time of his first project, Aluminum House:

Designing a single house is, to me, nothing less than a process of negotiating a hopelessly deep chasm between the designer (myself) and the client who ordered the design and will live in the house. Ideally one should speak not of “negotiating” but of “bridging” this chasm. But at the moment, there is virtually no common language with which to bridge it.1

Ito expresses a profound despair over this unbridgeable gap between the architect who designs a house and the client who will use or live in it. That despair, we may surmise, derived from his keen awareness of the circumstances of the architects in the 1970s who felt compelled to devote themselves to experiments with housing at the peripheries of society and the housing industry.

In that light, the activities of the Study Group were nothing if not an attempt to bridge this “hopelessly deep chasm” between designer and resident that Ito so frankly spoke of at the outset of his career. That is precisely why the group conducted client marketing surveys and published their proposals in popular magazines. Yet, in the end, their efforts did not bear the fruit they envisioned.

Today, Ito continues to speak out about architecture’s relationship to society and the architect’s role. The 1990s saw a shift in Ito’s focus from housing and commercial facilities to more public projects, beginning with the Yatsushiro Municipal Museum (1991), his first large-scale work of public architecture. Yet, even as he created works open to the public, this sense of estrangement never left him.

For that very reason, Ito took the lead in visiting various locales in the region stricken by the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, engaging in direct exchanges with the “architecture users” there (in other words, the disaster victims), and launching the Home for All project to build spaces for people to gather in these communities. Ito framed this project as an opportunity for architects to “break away from the notion of ‘works’ as personal expressions” and to reassess their role in society.2 The persistence of this concern on Ito’s part arguably demonstrates, however paradoxically, that the efforts of the Study Group failed (at least in his view) as a means of bridging that “hopelessly deep chasm.”

V. Taking the litmus test

Despite the tone of Ito’s recollections, our study of the written records kept at his office suggests that the Study Group was, in fact, extremely active. There must have been some sort of powerful motivation at work for a small architectural office to invest so much time and labour in research activities that offered no return to speak of. It is hard to believe that this Study Group didn’t hold considerable significance for Ito at the time.

One of Ito’s best-known essays is “There Will Be No New Architecture Without Immersion in the Sea of Consumption,” published in the journal Shinkenchiku in 1989. Writing in Tokyo, which the bubble-economy boom had transformed into the world’s ultimate consumer mecca, Ito declared that architecture had become nothing more than another “fashionable product to be consumed” like clothing and TV celebrities—and moreover, that architects would have to accept this state of affairs.1 Implicit was a biting critique of the elite architectural milieu and its contempt for the consumer-society masses.

-

Toyo Ito, “There Will Be No New Architecture Without Immersion in the Sea of Consumption,” Shinkenchiku (November 1989) ↩

The Commodity Housing Study Group can be seen as Ito’s first project to emerge from these concerns. The manifesto anticipates the idea that architects have no choice but to dive into the sea of consumption represented by commodified housing. A more direct expression of this view can be found in another essay by Ito, “Commodified Housing as Litmus Test,” which appeared in the architectural media around the same time as the launch of the Study Group. Though this text is not included in the massive two-volume collection of Ito’s writings published in Japan,1 it is a forceful assertion that architects of the present day must “step outside the domain of housing design, which they have come to see as a sanctuary…a last bastion where they can give air to their originality” and allow themselves to be “exposed to the merciless forces of commercialism.”2

“Sea of consumption,” “merciless commercialism,” and “commodified housing”—these concepts embody a common thread running through all three of the texts Ito wrote between the beginning and the end of the 1980s. By the same token, the perennial target of Ito’s fiercest criticism throughout this period was the stance held by the great majority of architects who chose to sequester themselves in a “sanctuary of housing design” rather than venture out into this new territory.

Throughout the 1980s, Toyo Ito consistently addressed the same fundamental concerns: How might architects overcome the predicament they found themselves in during the 1970s—their detachment from the mainstream construction industry? Could they forge a third path that neither clung to marginal experimentation nor gave itself entirely over to the industrial system? The Commodified Housing Study Group could be described as the first definitive action prompted by these concerns. Moreover, if the alienation that architects experienced in the 1970s was a logical endpoint to modern Japanese architecture’s development amid the vicissitudes of the Meiji era—war, defeat, and the postwar boom years—then Ito’s project was a critical practice rapidly deployed as a rebuttal to this historical trend. In that respect, it is an endeavour of inarguable historic value.

Translation from the original Japanese to English provided by Alan Gleason.

This essay is part of Meanwhile in Japan, a CCA c/o Tokyo project that includes three events in Tokyo, four web essays, and three volumes in the CCA Singles series.

Related articles