Corona Diaries

Samprati Pani observes a changing world

20 March: Absences

I am trying hard to not make sense of the world, intellectualize it, look at the funny side of things, prepare for the world to end, pass time binge watching Netflix, be productive, be slow, meditate, hyperventilate, worry, not worry, just be, just not be.

This morning I read about a man in Mumbai being slapped for sneezing without a mask.

I go down to buy groceries at my favourite kirana shop,1 and the shopkeeper informs me that he has run out of eggs. There had been a rush to buy eggs yesterday and someone had toppled his entire stack of egg crates. I walk back with a packet of bread, and no eggs and no butter and no paneer,2 all things I can do without, and pass by the shed of municipal safai karamcharis.3 One man is carefully hanging up washing on the park railing next to the shed… a pair of black socks and a black face mask. The family of dogs living around the shed seems to be in hiding. I cut through the park to make my way through my apartment back gate, and I am aware of how eerily quiet it is. There are two women, part of a daily group of five aggressive and we-will-not-give-way walkers, and one of my neighbours, walking on the track. And the gardener who is usually never around is raking the leaves. There is no one dropping feed for the pigeons, no flock of pigeons feeding and taking off, no kid watching pigeons, no cat waiting stealthily to pounce on them. There are no lovebirds trying to find an imaginary spot of privacy; no unemployed men passing time; no aunties chopping vegetables, chatting, or snoozing; no school kids bunking classes; no mad man trying to strike conversations with strangers.

I think of walking in Berlin. Many friends who had visited or lived in Berlin had told me that I would love Berlin because it is such a great place to walk. I did walk a lot in Berlin, but I would periodically get spooked by a sound that accompanied me while walking—the sound of my footsteps. They were never there back home. Equally spooky were the few pet dogs on the streets that never barked, the babies that never cried, the flowers that didn’t smell of anything, the pasta that didn’t taste of anything, and the excessive street graffiti that no one seemed to notice.

And I think of the mask drying on the railing.

24 March: Erasures

The Shaheen Bagh protest site was forcibly cleared after 101 days. It was cleared of the protestors and the structures—created in the course of the longest-running protest against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC)—which were ruthlessly dismantled and carried away. Portions of the graffiti on the wall outside the Jamia university were painted over. What fears are driving this urgency to erase? Or is it just petty spite?

I think of the many walks around the protest site, in the market lanes, on the footbridge, from the chai shop toward the stage and then toward the library. I think of thinking then, this will certainly not be here forever, but it will certainly be here tomorrow. I have woken up from a dream that lasted my entire life and I am too jetlagged from the long dream to grasp the hyperreality of the now. I have a sudden craving for a smell. A very specific smell from my dream. From a street corner. Of onions and green chilis and eggs being cooked, mixed with a faint smell of aloo parathas1 being fried, along with the dust of the city and the sweat of vendors hard at work in front of hot pans and the sweat of gym-returned men devouring hot eggs. And I am already feeling guilty. I am not sure if desiring the smells of crowded street corners is a crime in the world I have woken up to.

-

aloo paratha: a flat bread stuffed with spicy boiled potatoes ↩

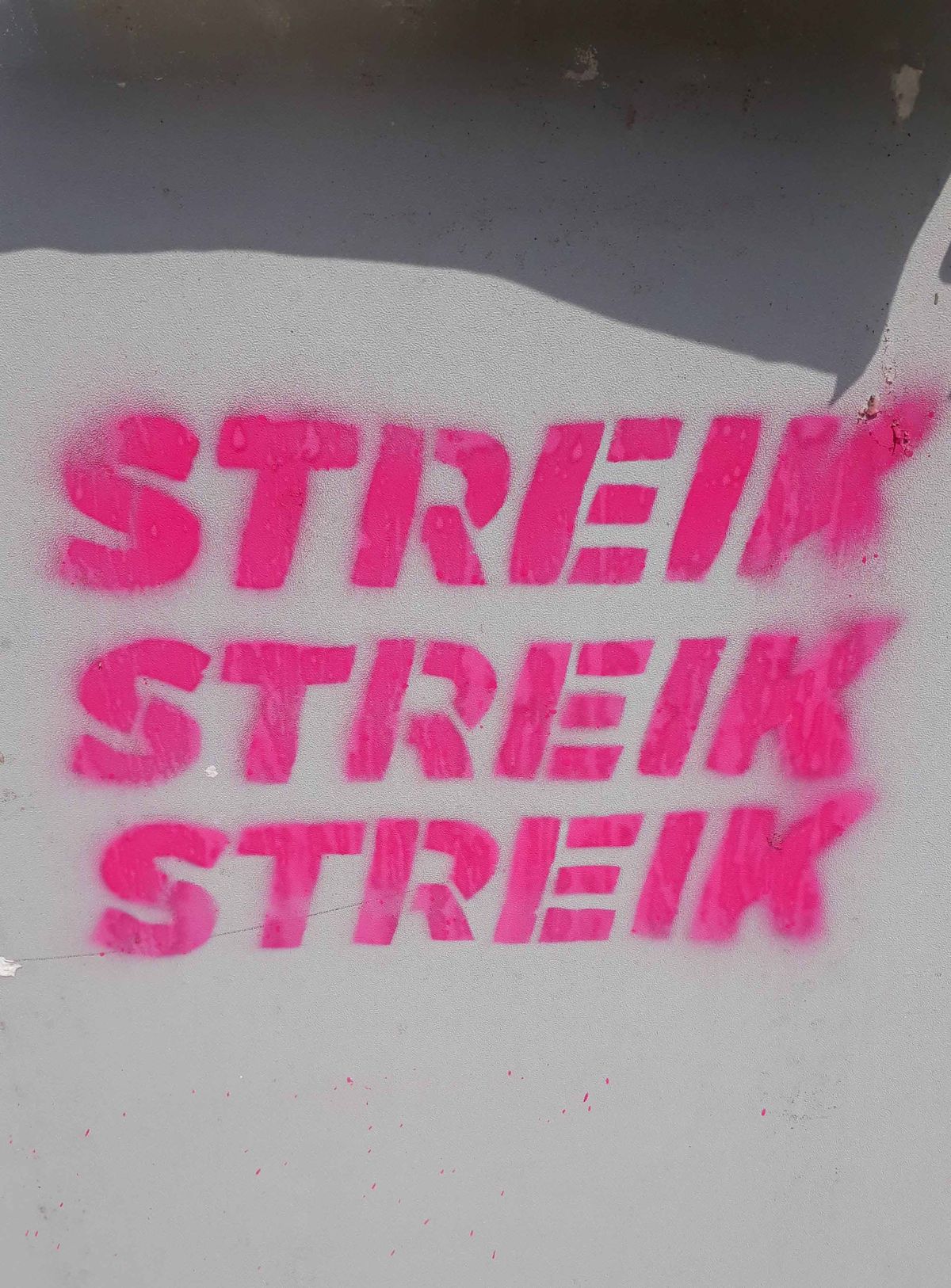

I distract myself by reading. I read about the history of women’s movements and protests in India and how the beating of thalis1 was used at different times to protest against price rise, domestic violence, rapes, and crimes against women.

And my mind wanders again. How does one protest in lockdown? How does one protest in times when there is only one enemy, and an invisible one at that? How does one protest in times when the symbolism of beating thalis has switched sides? And am I even allowed to think?

-

thali: a metal plate on which food is served ↩

29 March: Fears

The garden in my apartment block could not be more beautifully spooky. There are flowers in full bloom, looking brighter and bigger than usual, as do the blue butterflies, purple sunbirds, and parakeets. The old gardener, like all the other apartment staff—guards, garbage pickers, electrician, and plumber—has been coming in every day. He quietly works through the day, face mask in place, raking leaves, collecting seeds for the next season, mowing the lawn, watering the plants. And we are grateful to him for maintaining a garden that barely anyone uses now. Yes, we do our little bit to sanitize our guilt by feeling gratitude and dropping money in the donation box for a bonus to the staff coming to serve us in these difficult times, but we will not rush into decisions to implement a pay hike for the brave staff because these people must not get used to more. We will never intellectualize our lack of skill to tend to a garden or pick up and sort our own garbage, and when we go back to our dream lives, the same brave staff will go back to being just “lazy, unskilled people.”

Meanwhile, the air smells fresh and the birds seem nosier. The sound of drilling machines and construction work and incessant traffic is no longer background music to a day at home and over phone conversations on both sides. A friend complains to me about how there is a “new bird” in her neighbourhood, which keeps her awake at night. She can’t describe the bird’s call, and I try explaining that it is perhaps a nightjar or a barn owl, which has perhaps always been around, but she can hear it because she stays up longer now. But she insists it is a “new bird.” Another friend complains about noisy mynas that don’t let him work in the day.

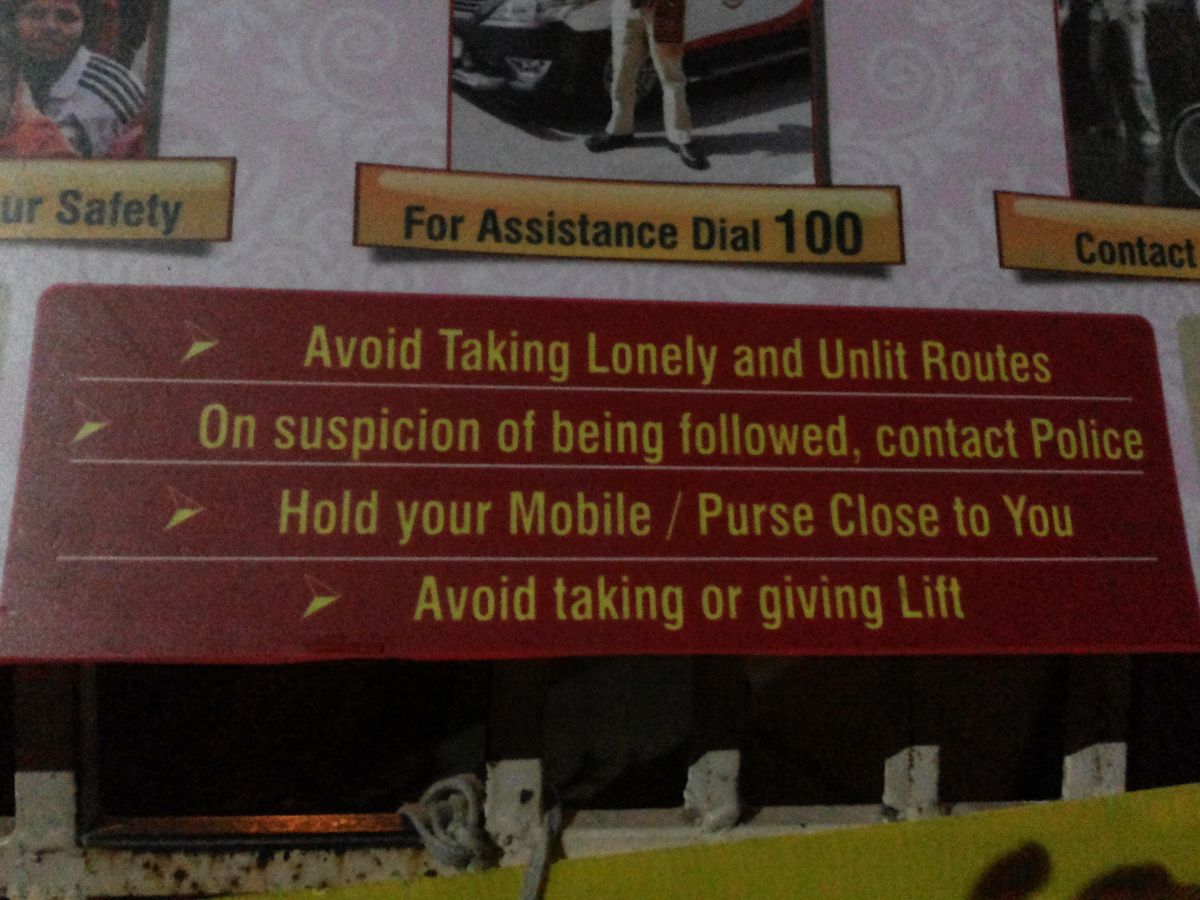

I think of the magpie, robin, and treepie I would see around a specific shrub and tree respectively in the public park behind my apartment. But I don’t dwell on them. They remind me of walks that made my dream life and routine, walks that happened unthinkingly, walks that I would never imagine as privilege. Now I walk across the same park to get my supplies from the market adjacent to it. I walk hurriedly, stopping just to quickly drop some food and water for the birds, but not taking a moment longer. I don’t go to see if the magpie, robin, and treepie are around. I don’t want to encounter human beings. My nose and throat start twitching the minute I step out of home, and I am scared to sneeze or clear my throat, finding no security in my face mask.

5 April: Forebodings

The nights are quieter than silence. Till I become conscious of the whirring fan and the sound of my breath, both of which then seem unnaturally loud. I don’t hear trains passing by or the occasional speeding cars and the wailing ambulances. The guards don’t blow their whistles at night… perhaps they think there are no thieves to scare away in a lockdown. The dogs interrupt the silence, wailing rather than barking, starting suddenly and then suddenly going quiet.

I have been thinking of the pickpockets who operate in Delhi’s weekly bazaars and crowded markets and streets. I have been thinking of them since the city announced the lockdown. Are they lining up to get a serving of khichdi?1 Or are they making the long walk to their villages? Do they even have villages they can call homes? I remember a conversation with a chaiwalla,2 who served tea to people queuing up at ATMs during demonetization. He told me that he knows who the thieves are but can’t reveal more. “Woh apna kaam karte hain, jaise main apna kaam karta hoon… hum sab gully ke paanchi hain—they do their work, like I do mine… we are all birds of the street,” he said. He explained that the bigger thieves are the rich who have money but are stingy about sharing their fortune.

The dogs have started wailing earlier today. Ten minutes before the night drill of dispelling darkness.

I miss the street birds.

This text was originally published on Chiragh Dilli. It is published here as part of our Of Migration web issue.