Bathing on the Canoe Jetty

Warebi Brisibe illustrates the space of the migrant female fisher

In considering the ways that Indigenous societies use language, art, and inflections to make sense of their lives, Linda Tuhiwai Smith discusses the use of non-textual sources, including orature through songs, storytelling and chants, relief sculpture, murals and patterns on walls, skin scarification, rock sketch art, and paintings, surmising that these forms of expression set Indigenous landscapes in a different frame of reference from the methods that govern Eurocentric cultures.1 Yet it is their use as a form of depicting social landscapes, lived experiences, and chronological events that make them vital as both forms of expression and research tools.2

-

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London & New York: Zed Books, 1999). ↩

-

Warebi Gabriel Brisibe and Ramota Obagah-Stephen, “Pictorial Storytelling,” Canadian Centre for Architecture, https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/78653/pictorial-storytelling. ↩

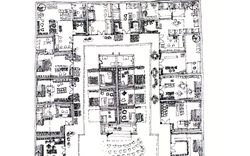

This ink and wash sketch was one of eight artworks I produced when studying with the Ijọ migrant fishers in the brackish water zone of the mangrove swamp regions of Bayelsa State in Nigeria, and the Bakassi Peninsula in Cameroon. The ink and wash sketch technique was adopted to create an imaginative pictorial composition exploring space, activity, and gender relations based on interviews with female fishers and female household heads of migrant fishing camps. It serves to combine different elements stemming from the imagination rather than from observation, and frames them within an artwork to offer a glimpse into the little-known world of the migrant female fishers. I attempted to use the sketch to depict key aspects of the social, economic, and cultural landscape through the eyes of the adult female fisher. The business of migrant fishing for the female fisher comprises a series of time-based activities in shared-access spaces, across an open aquatic range which consists of everything between the base camp dwelling and the sea—or in this case the river.1 In this environment, time is allotted to activity and activity to space, in a vicious socio-economic cycle. There is no such thing as wasted time as work time, family time, and even rest time are all accounted for by their connection to specific activities that occur within specific spaces.

In this context, adult female fishers function in one of two capacities: as either household heads where single, divorced, or widowed, or as fishing partners to their husbands and, in certain cases, their husbands’ other wives. Besides the actual task of landing the catch by setting traps or casting and hauling in nets, they are also responsible for making trade deals with fishmongers to get a good price for the fresh catch, smoking the leftover catch for preservation (which is often done while sleeping), tending to the family, and preparing food for the household. Women who are not married assume all of these roles single-handedly.

All activities in the migrant fishing camp revolve around the river. For these women, the river is not just an access route but serves equally as a foraging ground and area of production, bathing facility, lavatory, tutorial space, and play area for children, among other things. There is also an all-important anticipation of mobility, or the readiness to move to another fishing ground due to movements of pelagic fish species during a typical annual fishing cycle. This movement usually involves relocation of either the whole family or part of the family to another fishing ground during a certain time of the year.

The anticipation of mobility in connection with other key activities has resulted in the unique definition of spaces, and an ephemeral dwelling typology has come to define Ijọ migrant architecture.2 Spaces in this context are not confined to bounded interiors, but rather are connections between built form and nature. This flow between spaces is of significant importance to the community. In an environment like the mangrove swamp regions, spaces are designed almost entirely for functionality and rarely for comfort, and key activities occur in transitional spaces as well as thoroughfares like the raised platform of the canoe jetty.

This seemingly unassuming space designed in the similitude of a raised walkway accommodates and connects a plurality of activities. It acts as a laundry area, canoe mooring space, trading post, food preparation area, and outdoor relaxation deck—all tasks associated with the female fisher. As a connecting space, it links the dwelling to the lifeblood of the migrant fishing business: the river. Because of its multifacetedness, it appears to mirror a day in the life of the adult female fisher and thus serves as an ideal stage upon which to set this pictorial bathing scene. The sketch argues that the design of the Ijọ migrant fishing camp is adapted to the female migrant fisher and her nonpareil value in a seemingly male-dominated artisanal industry. Considering the scale of work and the time dedicated to it to achieve a successful fishing season—or sometimes to just break even—the sketch attempts to encapsulate what spare time could look like in the life of a female fisher in this rather harsh terrain. Tending to the child on a raised platform, which acts as a connecting walkway between the river and the dwelling, seems to be the only act that takes place within a space where work related to fishing does not await.

-

In a similar analysis of the architecture of coastal fishers in Sri Lanka, Shenuka De Sylva observed that in a fishing community, spaces accommodating daily activities are everything between the house and the sea. See Shenuka De Sylva, “Contested Thresholds and Displaced Traditions of Fisher Dwellings: A Study of Traditional Sri Lankan Coastal Architecture,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 20, no. 1 (2008): 82. ↩

-

Warebi Gabriel Brisibe, “The Dynamics of Change in Migrant Architecture: A Case Study of Ijaw Fisher Dwellings in Nigeria and Cameroon” (Unpublished PhD Thesis, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom, 2011). ↩