Dedicated to the Safety of Life and Limb

Elliott Sturtevant on the early twentieth-century rise of the safety expert

In 1904, The Outlook published an editorial detailing the unintended consequences of rapid industrialization and urbanization in the United States. The editorial noted how “[t]he frightful increase in the number of casualties of all kinds in this country during the last two or three years is becoming a matter of first importance. A greater number of people are killed every year by so-called accidents than are killed in many wars of considerable magnitude,” continuing that “it is becoming as perilous to live in the United States as to participate in actual warfare.” Among the “accidents” catalogued were a passenger train derailment caused by timber falling from a freight train, the explosion of a trolley-car after running over a box of dynamite dropped from a wagon, the collapse of an apartment building that crushed passersby in the street, a fatal train collision outside Knoxville, Tennessee, and on and on. “To these larger accidents must be added,” the editorial also reminded its readers, “the daily destruction of life by cable-cars, by the fall of elevators, and by reckless and incompetent drivers of automobiles.”1

Whereas the threats of nature—fire, disease, weather, and animals—had been of primary concern for earlier generations, human-made hazards—machines and the built environment—and new ideas about how best to manage them began to take precedence over the nineteenth century, particularly with the advent of the railroads.2 These hazards threatened human life and, perhaps more importantly, posed a growing danger to economic prosperity in the eyes of would-be reformers.

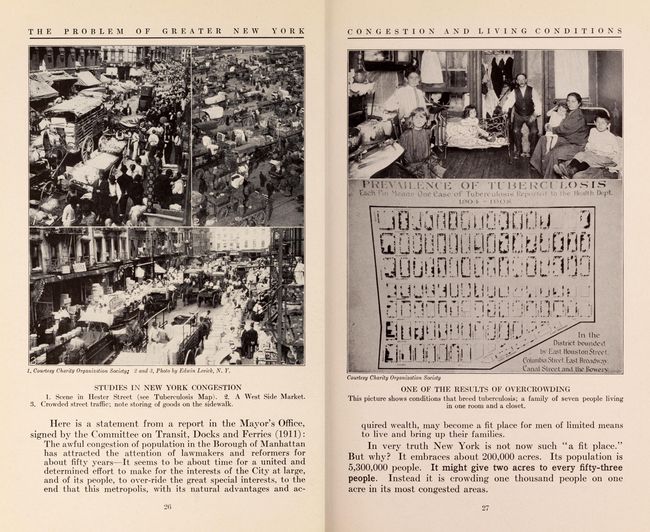

For example, in The Problem of Greater New York and Its Solution, Harry Chase Brearley linked fears about the city’s future “commercial supremacy” to the sorry state of its port facilities, its ongoing traffic problems, and citizens’ working and living conditions.3 Deploying a strategy adopted by photojournalist Jacob Riis in How the Other Half Lives, Brearley compared the dangers of “congestion” at the urban and domestic scales by pairing photographs of traffic in the city’s narrow streets with maps documenting cases of tuberculosis in its overcrowded tenement buildings. Elsewhere, Brearley contrasted an example of a well-lit, well-ventilated, fireproof workroom at Bush Terminal in Brooklyn with the dark interiors of Manhattan’s infamous sweatshops. The city and its industrial work environments were thus presented along a spectrum of human-made hazards needing professional remediation. The industrial city was at one end of this spectrum: the focus of city planners, housing advocates, and early traffic engineers’ designs and calculations. Fire remained a persistent threat.4 At the other end was the workplace, a space long shaped by conflicts between labour and capital and increasingly subject to reformers’ ambitions for frictionless operation and their elusive quest for ever greater “efficiency.”5

-

“The statistics of mortality from these sources ought to be collected,” it continued, “in order that the people of the United States may face the situation and understand how cheap human life has become.” “Slaughter by Accident,” The Outlook, 8 October 1904, 359. ↩

-

Arwen Mohun, Risk: Negotiating Safety in American Society (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013). ↩

-

Harry Chase Brearley, The Problem of Greater New York and Its Solution (New York: Search-Light Book Corp., 1914). ↩

-

Sara E. Wermiel, The Fireproof Building: Technology and Public Safety in the Nineteenth-Century American City (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000). For a more recent study, see Daniel Immerwahr, “All That Is Solid Bursts into Flame: Capitalism and Fire in the Nineteenth-Century United States,” Past & Present (2024), gtad019. ↩

-

On “efficiency,” see Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890–1920 (1959; repr., Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1999); and Samuel Haber, Efficiency and Uplift: Scientific Management in the Progressive Era, 1890–1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964). ↩

The emergence of the Safety First Movement and the role of the safety expert were part of this broader effort to abate security threats and fears at the turn of the twentieth century.1 Combining statistical analysis, the use of safety devices, regulation, and training, safety experts sought to install risk-managing techniques in the workplace and, by extension, the home and city. Depending on one’s perspective, these efforts could be considered part of a benevolent project to increase public and occupational health and safety or a means to further exploit workers by exerting greater control over their lives.

The American Museum of Safety in New York, founded by William Howe Tolman in 1907, was among the institutions dedicated to the cause of safety.2 In 1913, Tolman adopted an architectural metaphor to characterize the work that lay ahead for safety engineers and the broader safety movement: “In short, one of the most important phases of our future development is the work of creating an inexpensive, efficient hand-rail at the top of our industrial precipice to take the place of the unreliable and expensive ambulance at the bottom.”3 Tolman might have been thinking about the then-ongoing replacement of employers’ liability with workers’ compensation laws.4 Still, his metaphor got to the core aspect of the safety project: safety experts hoped to mitigate short-term losses to ensure long-term gains.

-

Mark Aldrich, Safety First: Technology, Labor, and Business in the Building of American Work Safety, 1870–1939 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997). ↩

-

Ross Wilson, “The Museum of Safety: Responsibility, Awareness and Modernity in New York, 1908–1923,” Journal of American Studies 51, no. 3 (2017): 915–938. ↩

-

William Howe Tolman and Leonard B. Kendall, Safety: Methods for Preventing Occupational and Other Accidents and Disease (New York: Harper, 1913), 8. ↩

-

In the 1910s, at least two dozen states passed laws that guaranteed some form of compensation to workers injured on the job. David Rosner and Gerald E. Markowitz, eds., Dying for Work: Workers’ Safety and Health in Twentieth-Century America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), xiv. ↩

Building a “Museum of Social Economy”

Before founding the American Museum of Safety, Tolman had been selected by the President of the League of Social Service Josiah Strong to put together an exhibition on the condition of American cities. First exhibited in a Manhattan socialite’s home, Tolman’s work was then chosen as one of the US government exhibitions in the Palace of Social Economy at the 1900 Paris Exposition. Tolman’s display was located near the “American Negro Exhibit,” which featured W.E.B. Du Bois’s data visualizations, as well as models of New York’s “tenement-house district”.1 This was fitting since Tolman and Strong had been inspired by Paris’s Musée Social, a legatee of the “social economy” exhibits from the city’s prior world fair. Their exhibit included information on what employers were doing to improve employee conditions, the work of the church, other organizations such as the Salvation Army and YMCA, and municipal betterment programs.2 Elsewhere, the 1900 Paris Exposition hosted exhibitions assembled by the continent’s leading “labour museums” that similarly hoped to document efforts to improve the living and working conditions of the labouring classes.3

After the exhibition closed, Tolman and Strong advanced a vision for creating an institution with a similar vocation in New York. This “Museum of Social Economy,” as Tolman first referred to it, planned to use the items displayed in Paris as its “nucleus.”4 As The New York Times later explained, this museum would “contain carefully collected data—books, reports, documents, photographs, charts, and the like—by which a comprehensive study could be made of the park systems, the public baths, the street cleaning and disposition of garbage, the light and water systems, fire department, the housing problem, &c., of any considerable city in the land, and of all the great cities in the world.” In addition, materials on so-called industrial betterment—“what the wealthy employer is doing to improve the moral and intelligence of his workers, the most approved methods of hygiene in factories, the beautifying of the working man’s home”—would supplement the documentation of municipal achievements.5

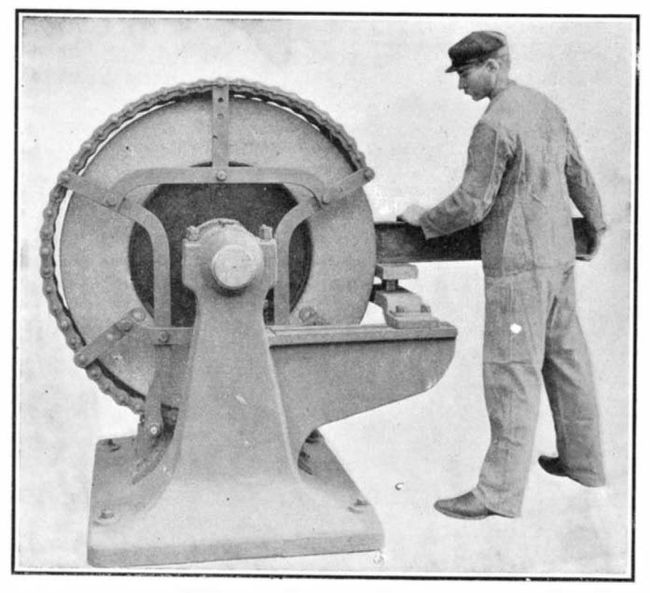

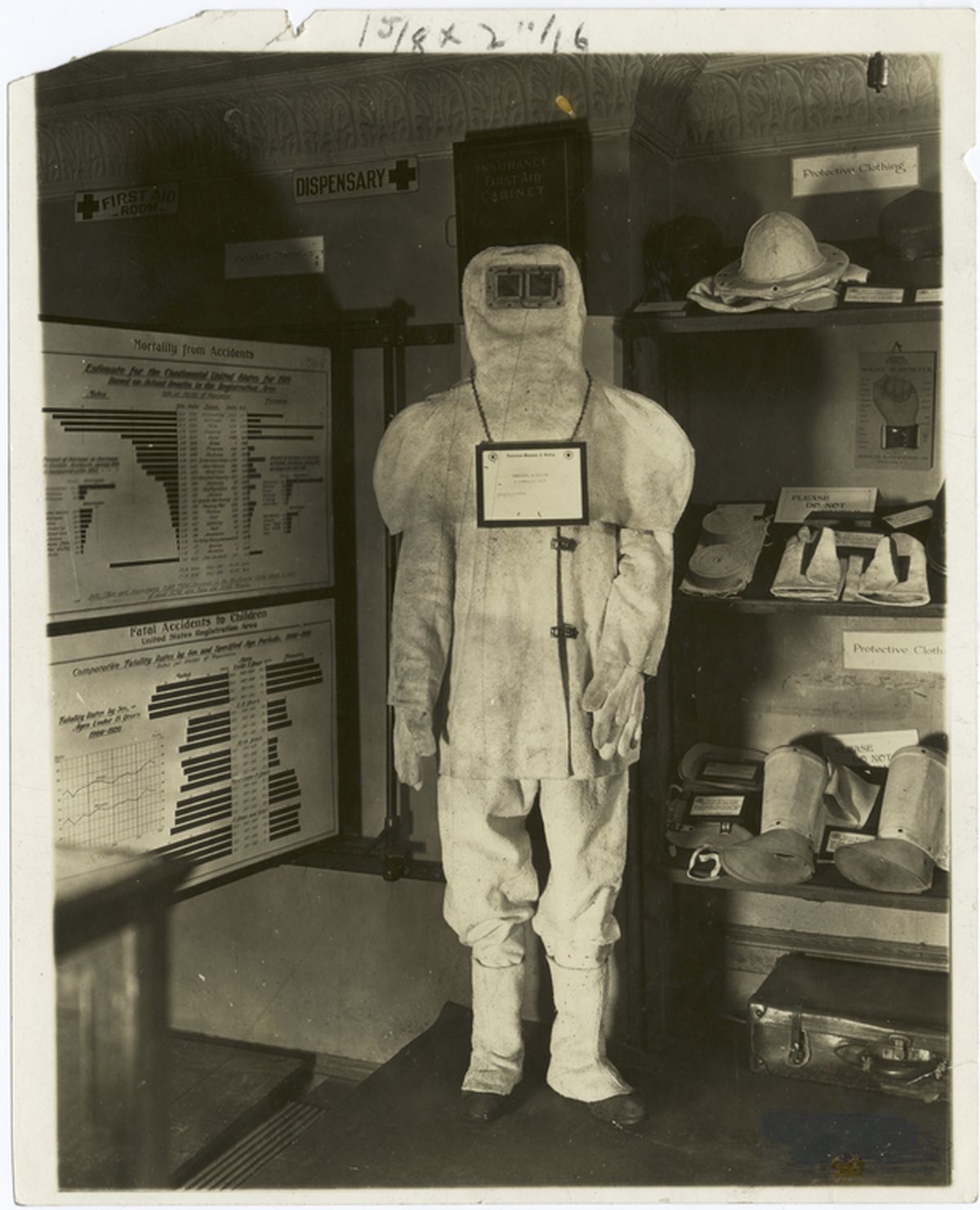

The International Exposition of Safety Devices and Industrial Hygiene, held at the American Museum of Natural History in 1907, catalyzed the formation of Tolman’s museum.6 Over three hundred companies participated in this showcase of efforts to preserve human life. At the exhibition’s inaugural dinner, New York State Governor Charles Evans Hughes quantified the severity of the problem, suggesting that the number of people killed or wounded in various industries in the United States approached 500 000 a year. This represented a tragic loss of life, but also, from an economic perspective, an inexcusable waste of human resources. To combat what Scientific American referred to as “the day-by-day carnage and mutilation which occur in the prosecution of the so-called peaceful arts,” the exhibition featured a range of safety devices, many of them relatively inexpensive attachments designed to prevent machines from injuring their human operators.7 These included shields for fast revolving grinding wheels that might be prone to exploding under stress, casings around gears and pulleys, and emergency stops that were designed to reduce workers’ chances of being maimed. The exhibition’s success led to the founding of the “American Museum of Safety Devices and Industrial Hygiene” later that year.8

-

William Howe Tolman, “Social Economics in the Paris Exposition,” The Outlook 66 (1900): 311–318. ↩

-

Tolman, “Social Economics in the Paris Exposition,” 318. ↩

-

Leopold Katscher, “Modern Labor Museums,” Journal of Political Economy 14, no. 4 (1906): 224–235 ↩

-

Tolman, “Social Economics in the Paris Exposition,” 318. ↩

-

“A Social Museum for New York,” The New York Times, 13 April 1902. ↩

-

“An Exposition of Safety Devices and Industrial Hygiene,” Scientific American (26 January 1907): 93–94. ↩

-

“The ‘Casualty List’ of American Industries,” Scientific American (9 February 1907): 126. ↩

-

The institution was renamed the “Museum of Safety and Sanitation” when it relocated to the United Engineering Societies’ Building at 29 West 39th St. in 1910. Wilson, “The Museum of Safety,” 923. ↩

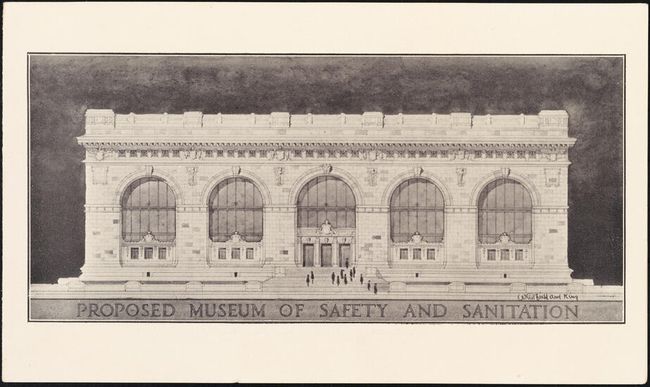

The American Museum of Safety

In 1910, after moving into the United Engineering Societies Building, the museum gained the support of the Carnegie Corporation and formally changed its name to the “American Museum of Safety.” The museum had begun publishing a bulletin featuring the latest safety devices, titled Safety, in 1909, and began hosting regular talks from leading experts. The institution also put forward plans for a new building. Following a series of industrial accidents in the early 1910s, including the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 25 March 1911 and the sinking of the Titanic on the night of 14 April 1912, the museum’s efforts, and the safety movement more broadly, gained prominence and urgency. But rather than advocating for greater regulatory oversight, the museum, mirroring the movement, foregrounded the need for greater individual responsibility, shifting responsibility for safety from the state, municipality, and employer to the individual worker.

Take, for example, the museum’s Manuals of Safety, which canvassed broad issues plaguing the workplace. In “Alcoholism in Industry,” Tolman shared efforts made by European employers to reduce accidents linked to intoxication at work. A tea canteen had been opened at the AEG factory in Berlin, serving cold drinks in summer and warm drinks in winter, and at the Hamburg American-Line, a canteen sold lemonade and seltzer. But Tolman argued that this problem was not solely the employers to solve; the men were at fault, as were their wives! “It sometimes happens that the wife is too indifferent or ignorant to prepare a suitable midday meal,” Tolman wrote, “compelling the men folks to allay the stomachic craving by liquor.”1 The employers’ safety programs thus concerned workmen’s domestic lives, too. As Tolman remarked, “It has been discovered that the hygiene and care of the home is closely connected with healthful conditions of life, which, in turn, ward off the insidious attacks of disease, and by means of a healthy body tend to allay the craving for alcohol.”2

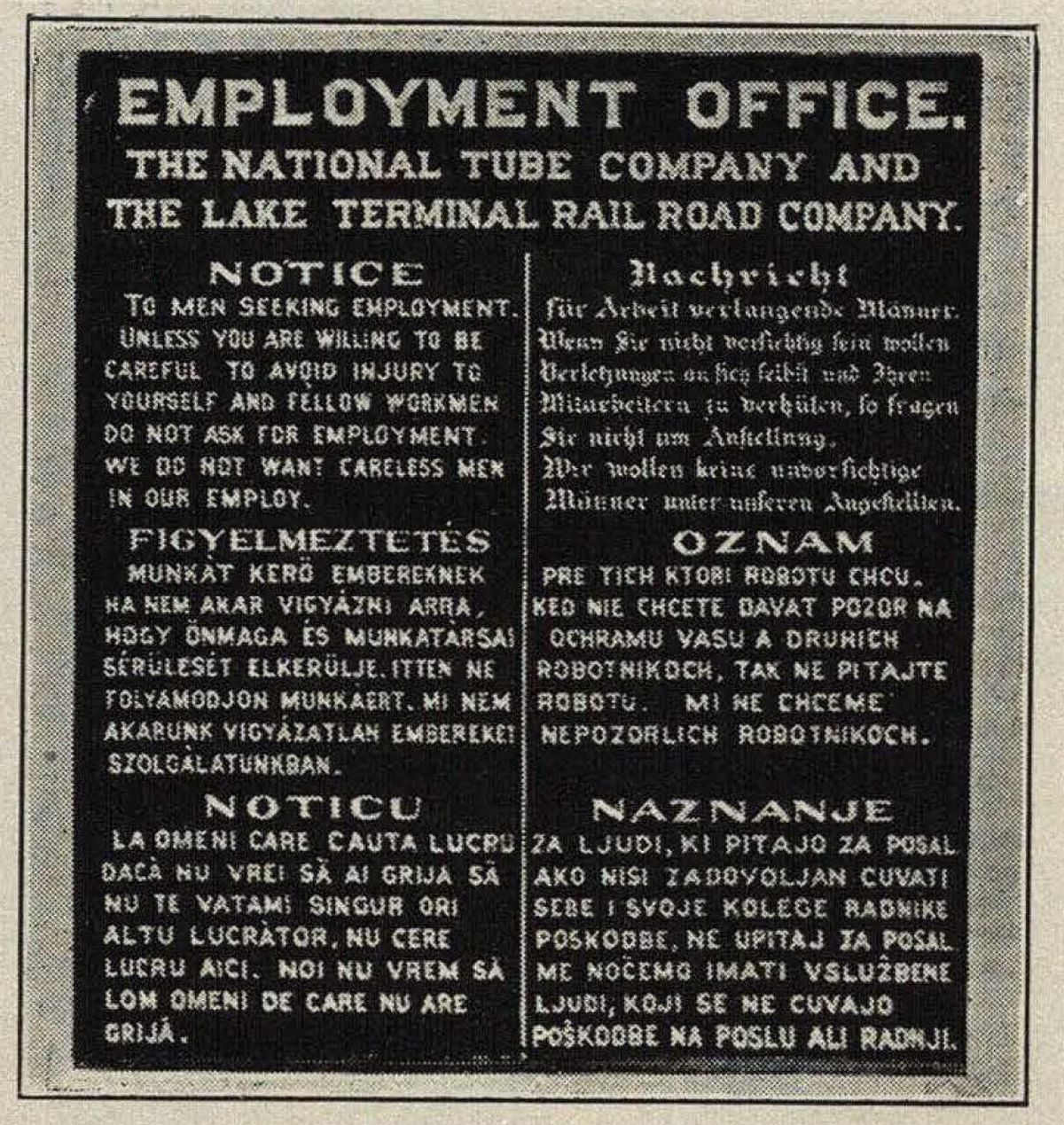

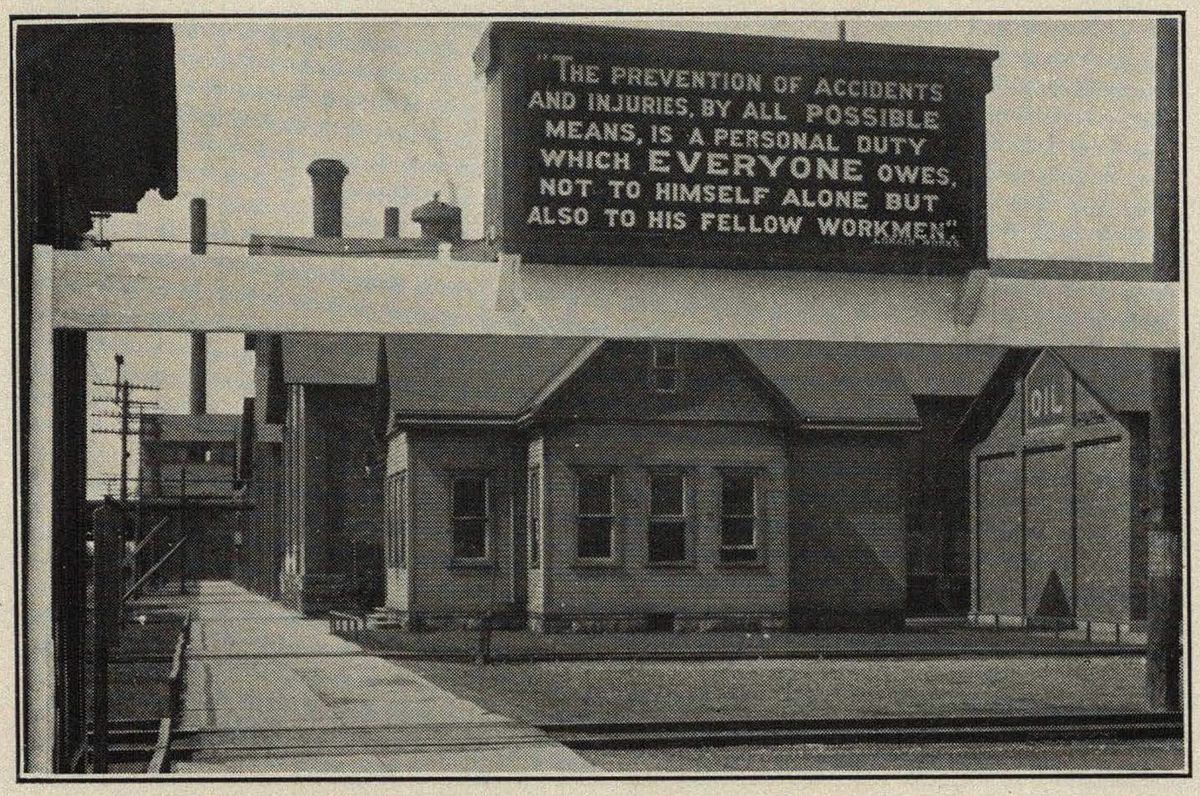

Often, employers responded with medical exams and other means of screening accident-prone workers rather than providing better working and living conditions. The museum’s subsequent manual, “Yard Practice,” reproduced a sign translated into six languages that hung outside the Employment Office of the National Tube Company and the Lake Terminal Rail Road Company. “To men seeking employment,” it read. “Unless you are willing to be careful to avoid injury to yourself and fellow workmen do not ask for employment. We do not want careless men in our employ”.3 Safety was a worker’s virtue, rather than an employer’s responsibility. Workers, particularly new immigrants, were described as “careless” and “reckless” and accidents were often framed as their fault.

-

William H. Tolman, “Alcoholism in Industry, Some European Methods of Prevention,” Manuals of Safety 1 (New York: American Museum of Safety, 1911), 8. ↩

-

Tolman, “Alcoholism in Industry,” 10. ↩

-

Charles Kirchhoff and William H. Tolman, “Yard Practice, Walks and Railings,” Manuals of Safety 2 (New York: American Museum of Safety, 1912), 10. ↩

The Economy of Accident Prevention

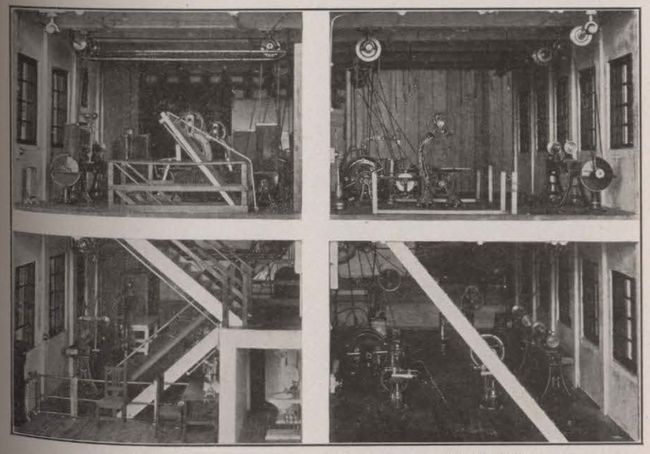

When safety engineers did intervene, they often resorted to safety devices, including guards, goggles, respirators, and what we might consider improvements to the architecture of work. Description and presentation of these interventions constituted much of the museum’s exhibitions. In 1917, for example, the Aetna life insurance company donated its displays from the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition, which included a series of fully safeguarded modern, motor-driven machines, as well as a model factory building.1 Representing a two-storey brick mill building, the model was divided in two by a firewall that extended through its roof. One side was labelled “safe”; the other, “unsafe.” On the “safe” side, the stairway was built at a proper angle, with standard rails and a landing halfway down. On the “unsafe” side, the angle was acute, and the handrails were absent. A hole in the floor was similarly left unguarded. On the “safe” side, the machines were equipped with guards, and the grinding and polishing machines were equipped with exhaust systems to limit the inhalation of dust. The overhead belts were guarded, and the motors were enclosed with wire mesh. An emergency room with a first-aid cabinet, bed, and chairs was on the second floor. The “safe” side also included a separate office, sanitary toilet facilities, miniature steam radiators, and electric lamps arranged at regular intervals, with shades designed to limit unwanted glare. Its interior walls were also painted white. As the journal explained elsewhere, darkness tended to attract dirt and often led to a “total disregard of ‘good housekeeping.’”2 The “safe” side was equipped with a miniature sprinkler system and a tin-clad fire door, marked with a green light and leading to an all-metal fire escape. On the “unsafe” side, there was no escape.

Many similar devices, additions, and considerations had been featured in Safety Methods for Preventing Occupational and Other Accidents and Disease, a book Tolman co-authored with Leonard B. Kendall. Divided into three main sections, the book discussed “danger zones,” including catwalks and machines; the concept of “industrial hygiene,” which referred to workers’ potential exposure to harmful chemicals and poisons; and “social welfare,” which extended the question of safety to that of industrial education and workers’ lives outside the factory. As Tolman wrote in the book’s opening pages, “It is the general opinion of the engineering profession that one-half the accidents in the United States are preventable, and that a conservative estimate of the annual number of accidents which result fatally or in partial or total incapacity on the part of the worker may be placed at 500 000. Reckoning the wage-earning capacity of the average workman at $500 per annum, we have to consider a social and economic loss of $250 000 000 a year.”1 Industrial accidents were deemed a waste in both human and financial terms.

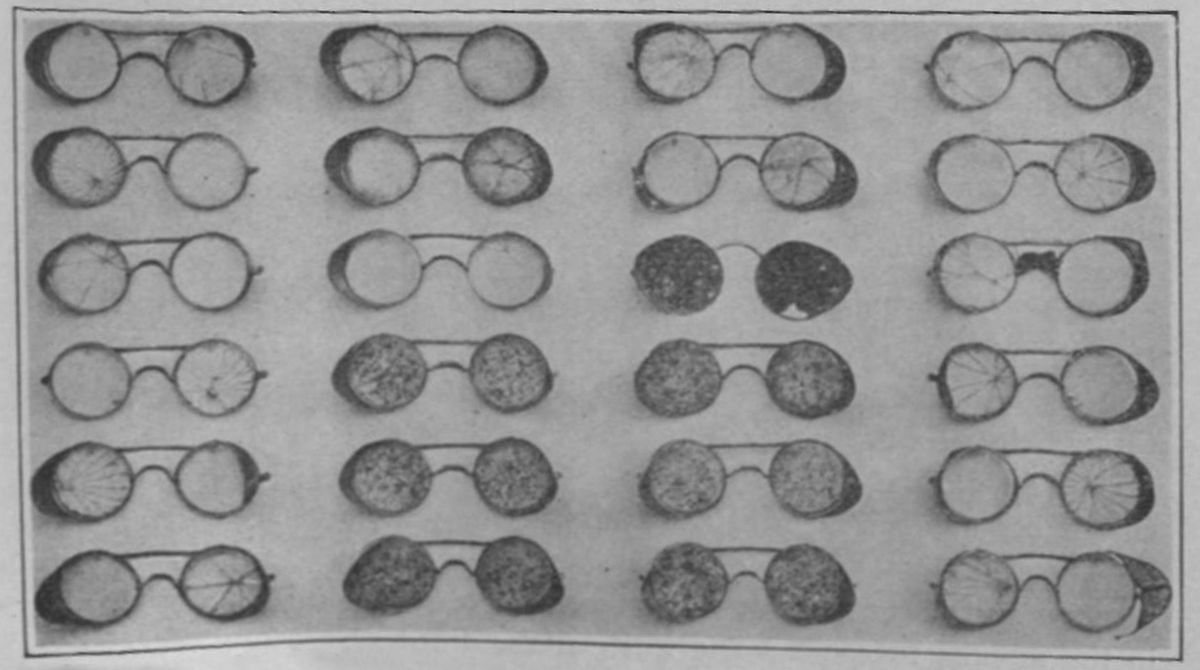

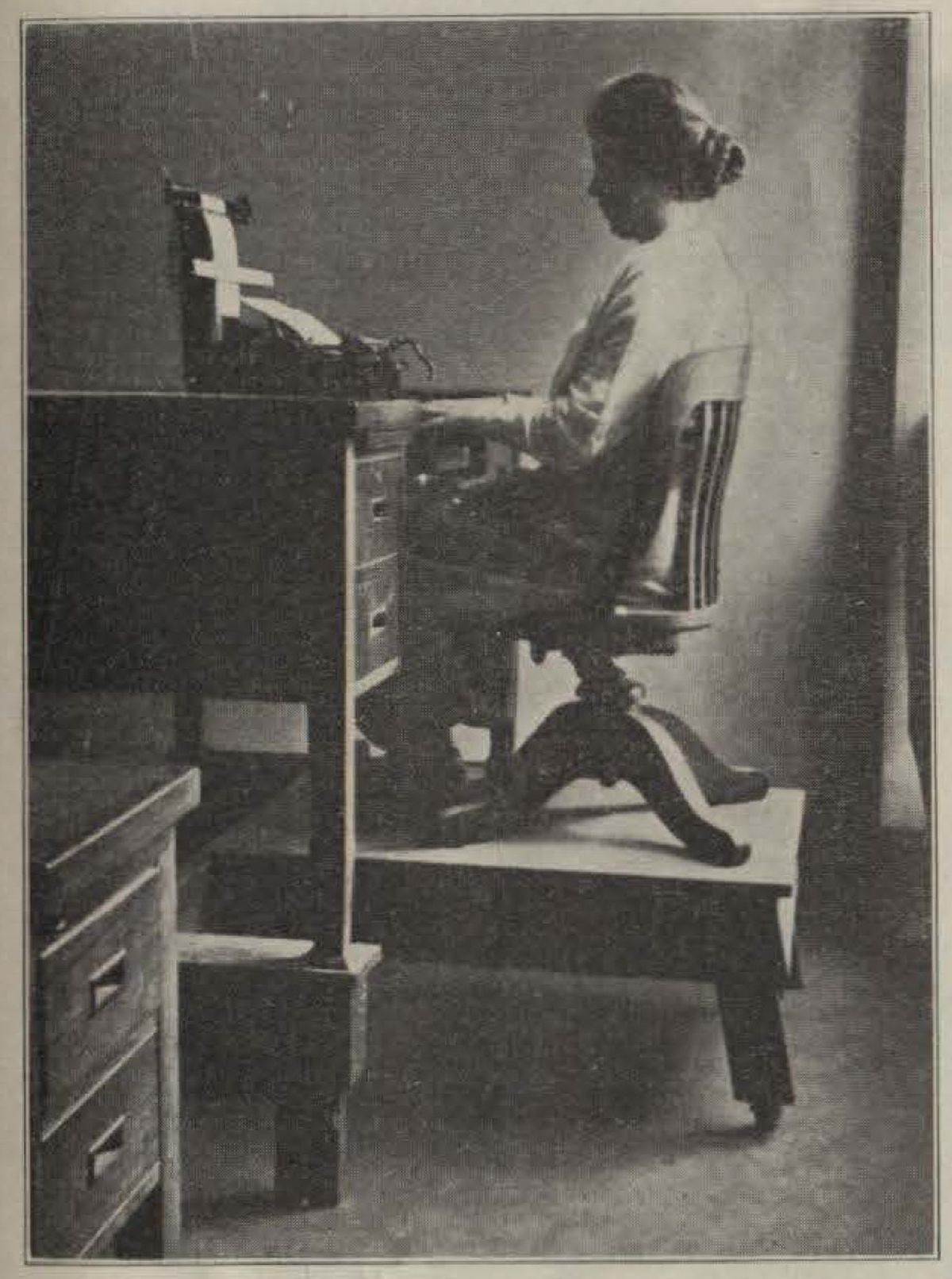

In the pages of Safety and among the exhibits of the American Museum of Safety, we witness a collection of products that often made preserving human health subservient to economic equations.2 To repeat a phrase the Occupational Health and Safety Administration, a postwar outgrowth of the movement, still uses today: “Safety Pays.”3 But who ultimately benefitted from these devices, interventions, and considerations? A photograph of two dozen cracked safety glasses implies an equal number of equally grateful workers. The man about to enter a sewer equipped with a Barnum Respirator also probably appreciated a little extra fresh air. The women depicted in the pages of Safety displaying “wasteful postures,” however, may have wondered who benefited from replacing their chairs with a variety of “fatigue-eliminating equipment.”4 And the men who were garbed head-to-toe in fireproof, asbestos-lined suits may have later regretted their decision; ultimately, they may have paid with their lives.

-

Tolman and Kendall, Safety, 2. ↩

-

Trade catalogues for many similar products can also be found at the CCA; see, for example, the Harris System Portable Fire Escape, Edison Electric Safety Mine Lamp, and Carborundum Anti-Slip Tile, among many others. ↩

-

“The Safety Pays Program,” OSHA states, “raises awareness of how occupational injuries and illnesses can impact a company’s profitably.” “OSHA’s Safety Pays Program,” Occupational Safety and Health Administration, https://www.osha.gov/safetypays. ↩

-

Frank B. Gilbreth, “Wasteful Posture,” Safety 6, no. 9 (June 1922): 147–150. ↩

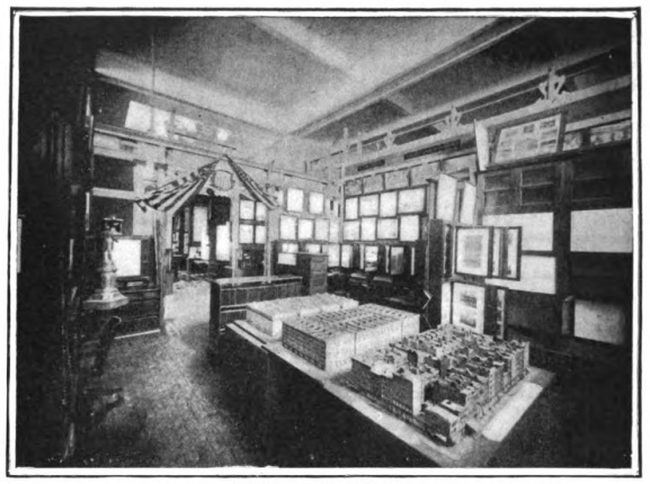

Following the war, interest in the museum waned. Other institutions, such as the National Safety Council, achieved greater prominence, and interest in the “museum,” as a means of public engagement, increasingly fell out of favour. By the time Scientific American published a series of images of the museum’s interiors, titled “Dedicated to the Safety of Life and Limb,” the institution was on its last legs.1 Shortly after, a Bureau of Public Safety was established in the city’s police department, signalling a shift in the meaning of “safety” from an aim of social reform to a justification for greater surveillance and policing.2 That said, it’s nevertheless a compelling exercise to consider what a “Museum of Safety,” or a similar institution, might look like today. What devices would it display? What information would it gather? And what role might it play in preparing, for lack of a better term, society for the “dangers” of the twenty-first century? Or better yet, how might it replace earlier designs on “safety” with a new emphasis on “care”?

-

“Dedicated to the Safety of Life and Limb: The Safety Museum in New York City,” Scientific American 130, no. 6 (1924): 401. ↩

-

Ross Wilson, “Safe in the City: Risk in Early Twentieth-Century New York,” The Gotham Center for New York City History, 9 November 2016 https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/safe-in-the-city-risk-in-early-twentieth-century-new-york ↩