Black Bodies, (un)Safe Spaces

Simphiwe Mlambo on surveillance architecture in Johannesburg

In a context of historic racial oppression such as Johannesburg, surveillance systems and architectural elements both reveal the ongoing challenges faced by “unidentified” Black bodies and amplify spatial disparities. Surveillance reinforces the insidious social construct of whiteness, perpetuating harmful racial stereotypes and criminalizing the suffering of Black people1—under the guise of ensuring so-called safety.

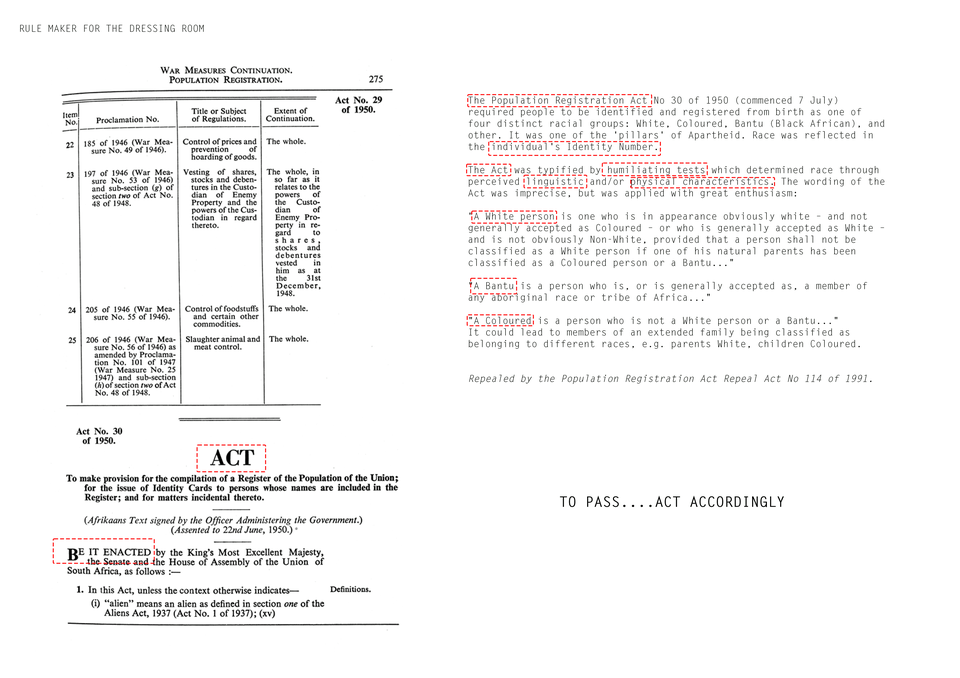

Historically, the Population Registration Act No. 30 of 1950 facilitated the implementation of various discriminatory policies and laws that governed social and economic interactions among different racial groups, effectively institutionalizing racial segregation across all aspects of life in South Africa. The Population Registration Act required citizens to carry identity documents clearly indicating their racial classification.2

Today, remnants of these regulations continue to impact how Black people experience space. The projection of Blackness onto a body in space constructs a spatial imaginary that, when circulating through checkpoints and surveillance architectures (video, identification scanning, etc.), renders Black bodies as non-human and not belonging to any place. The over-surveillance of Black communities contributes to a cycle of criminalization and construction of the non-human existence of the Black body and, consequently, its control. Black individuals are more frequently subjected to stop-and-search tactics by police, which perpetuates a narrative of suspicion and reinforces negative stereotypes.

-

In his work, Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America, Yancy argues that the “white gaze” not only objectifies Black bodies but also distorts perceptions, leading to systemic injustices that dehumanize and marginalize Black communities. George Yancy, Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016), 21. ↩

-

Alistair Boddy-Evans, “South Africa’s Apartheid Era Population Registration Act,” ThoughtCo, https://www.thoughtco.com/population-registration-act-43473. ↩

Surveillance Mechanisms

For instance, American philosopher George Yancy discusses how the “elevator effect” —in which a white woman perceives him as a threat upon entering an elevator with him—illustrates the pervasive anxiety that white individuals experience in proximity to Black bodies, leading to behaviours that reinforce racial hierarchies.1

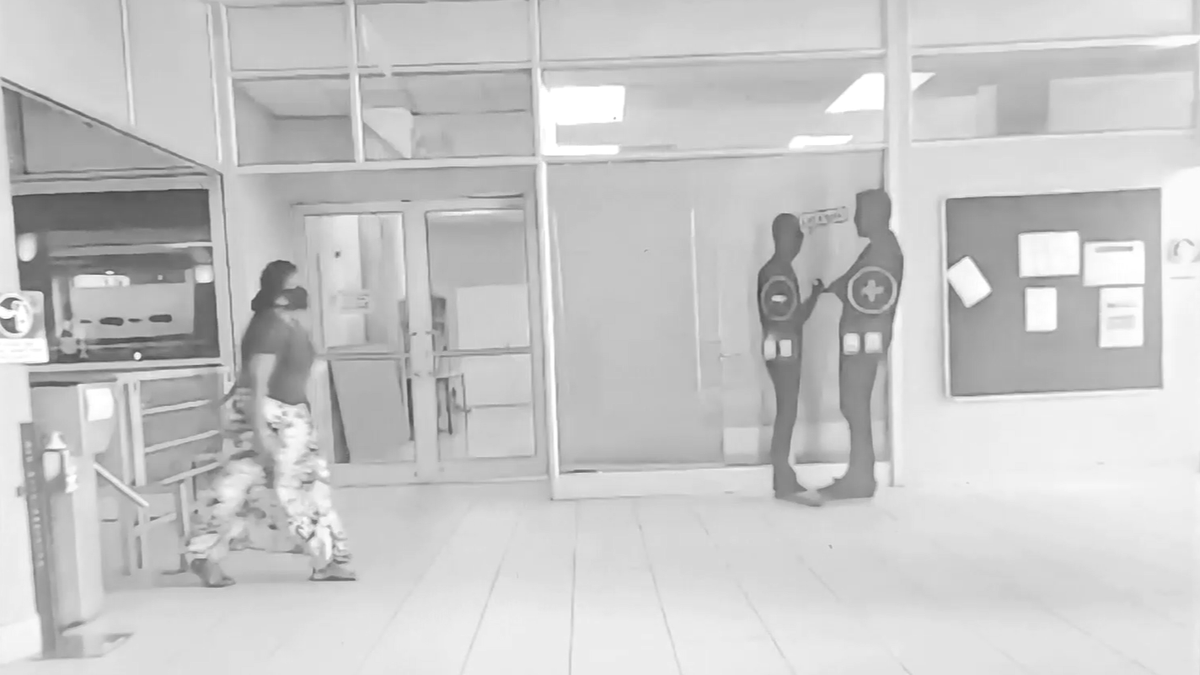

The architectural landscape in urban areas often reflects dual purposes: while some structures are designed for community engagement and inclusivity, others serve as fortifications against perceived threats. This dichotomy is evident in university campuses where secure access points are juxtaposed with open spaces meant for social interaction.

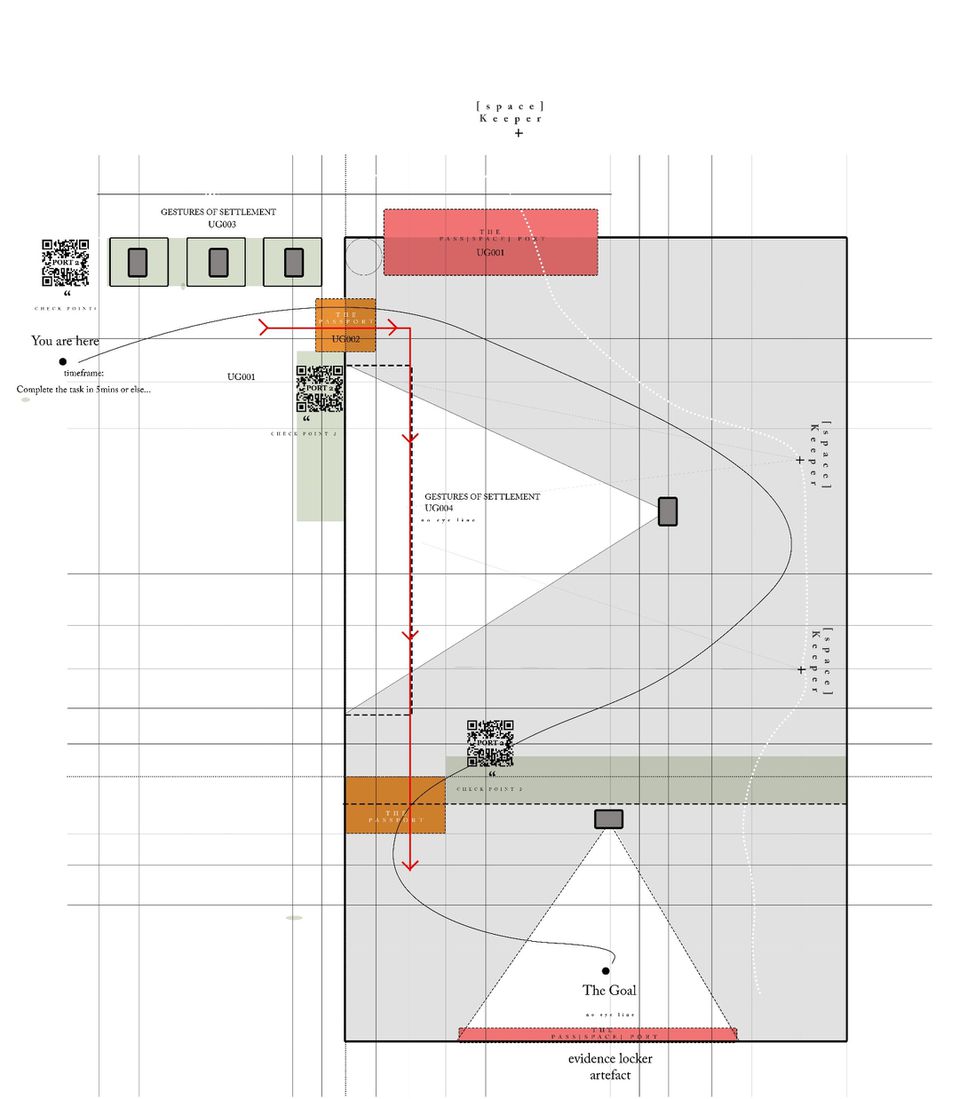

The University of Johannesburg, a predominantly Black university, initiated regulations for 2022 where students were required to carry access cards. By drawing parallels between the Population Registration Act and part 7 of these University student regulations, one can observe a trend of over-surveillance that leads to invasive monitoring of student behaviours. This creates an atmosphere where students feel under constant scrutiny. The result is a complex interplay between historical injustices and contemporary realities, where remnants of apartheid continue to shape the lived experiences of Black South African students today.

-

Yancy, Black Bodies, White Gazes ↩

Racial Implications

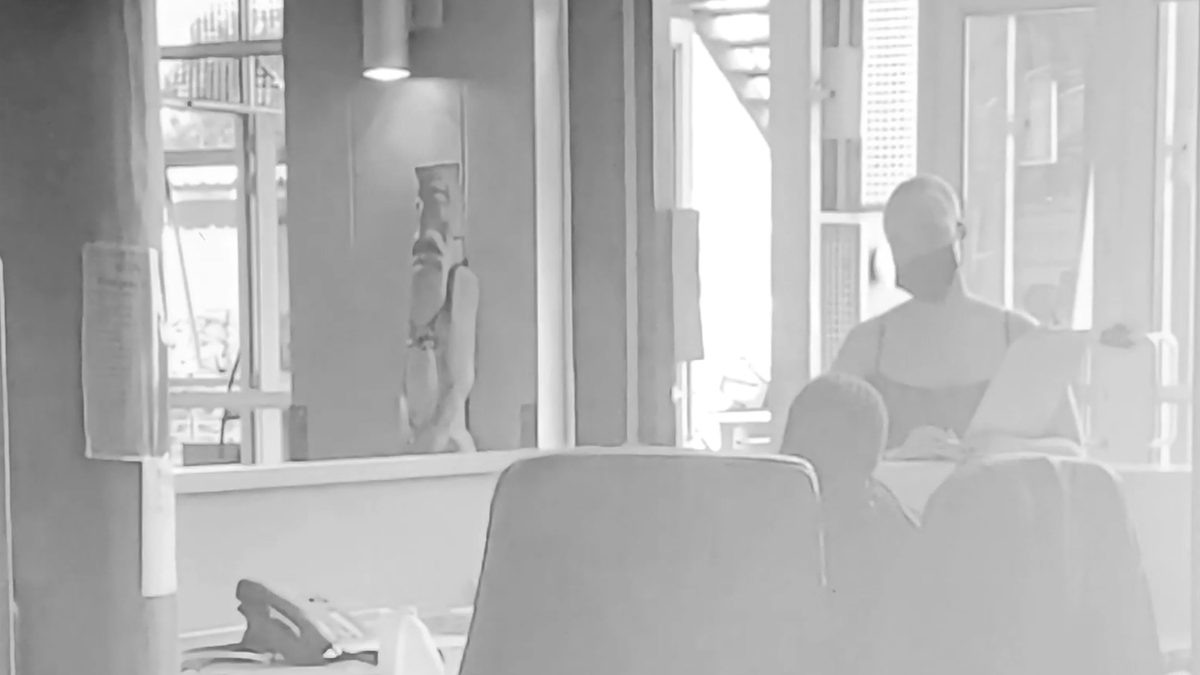

The pervasive use of surveillance technologies like turnstile card identification and fingerprint recognition, at all prominent entry points into the university, raises concerns about privacy and the potential misuse of data, especially in contexts where marginalized groups are disproportionately affected.1 When these technologies target areas with higher populations of Black students, they further entrench the perception that these individuals pose a threat.

Simone Browne’s concept of “racializing surveillance” describes how surveillance practices define norms around race and exercise power over marginalized communities.2 South African policing strategies often reflect and reinforce racial hierarchies. The ongoing use of racial classification for monitoring purposes continues to perpetuate divisions and inequalities.3 The legacy of these laws has persisted, influencing contemporary policing practices.

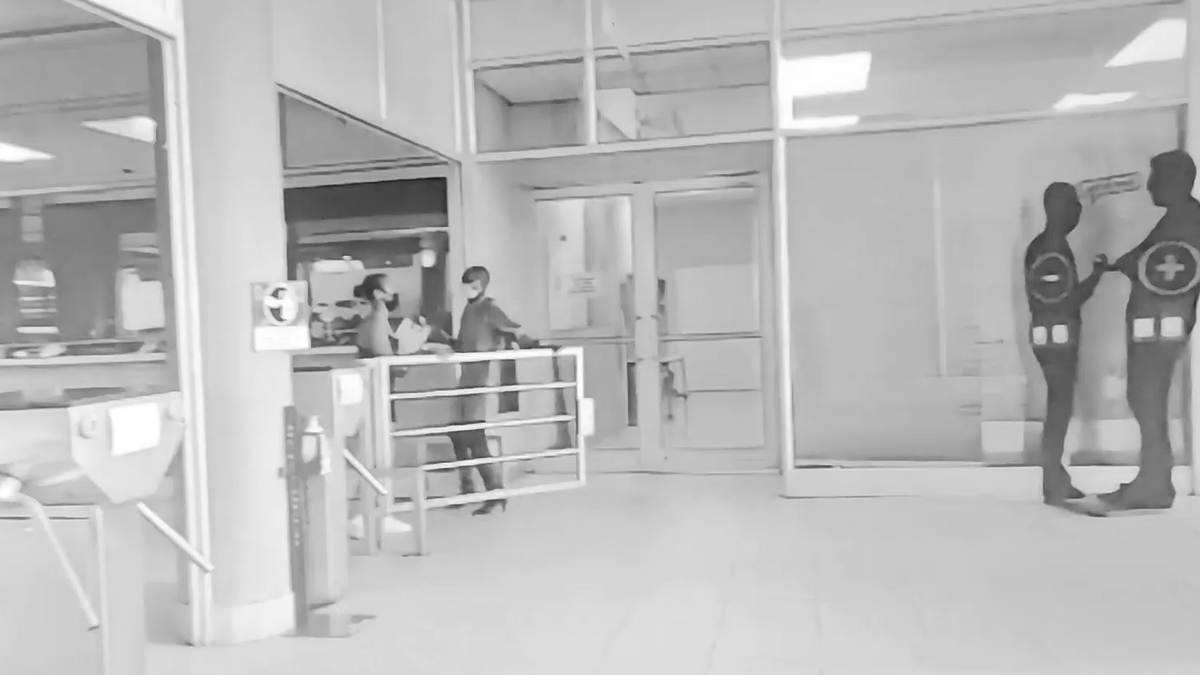

This dynamic is observed at the entrances to South African universities through interconnected architectures involving security personnel that transition from intangible surveillance to tangible barriers when alerted by turnstiles denying entry to students without their access cards—viewed from security desks resembling watchtowers. These architectural mechanisms serve as physical manifestations of social borders that categorize individuals based on race.

Notably, there is a subtle shift in levels of aggression exhibited by security personnel towards Black students at moments of non-identification. This reflects remnants of apartheid-era surveillance architectures designed for racial segregation and oppression. During apartheid, extensive surveillance measures were employed to monitor and control the Black population, including pass laws that criminalised their movement.

The ongoing reliance on racial classifications for data collection and policymaking demonstrates how deeply ingrained these categories are in South African society. While some argue that such classifications are necessary for addressing historical inequalities, others contend that they perpetuate division.

-

In a law review article by Danielle K. Citron, the University of Virginia School of Law argues that teachers, administrators, and school resource offices have the tools to watch — in real time — students’ searches, emails, chats, photos, calendar invites, geolocation and more, according to Citron’s research. Private companies are facilitating this continuous and indiscriminate surveillance by scanning, tracking, and analyzing the most intimate aspects of young people’s lives. Her article, “The Surveilled Student,” which is forthcoming in the Stanford Law Review, provides an analysis of the costs and benefits of this surveillance and identifies the underlying legal issues. Danielle Keats Citron, “The Surveilled Student,” (August 25, 2023), Stanford Law Review 76 STAN. L. REV 1439, (2024): 1439-1472. ↩

-

Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press, 2015), 16-17. ↩

-

“Race in South Africa: ‘We haven’t learnt we are human beings first’,” BBC, 20 January 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55333625. ↩

Contemporary Realities

This ongoing struggle highlights a broader issue within contemporary South Africa, where turnstiles at universities serve as a reimagined passbook that monitors and restricts movement, particularly criminalizing the presence of Black students. Within this surveillance architecture, Blackness is often perceived as “unsafe,” further entrenching spatial disparities and challenges faced by Black individuals. Such dynamics manifest through acts of denial of entry, harsh reprimands, ridicule, and, in extreme cases, arrests during protests like those seen in the #FeesMustFall movement.1 This intersection of educational access and systemic inequality continues to resonate deeply with South Africa’s youth, fueling ongoing activism and resistance.

In contemporary Johannesburg, Black bodies remain vulnerable to both subtle legislative measures and overt surveillance systems. These surveillance architectures not only draw from but also reinforce the spatial practices established during apartheid. The physical and experiential dimensions of movement within urban spaces perpetuate existing cultural norms and expectations. The implications of these surveillance practices extend far beyond mere observation; they actively shape societal perceptions and interactions, embedding racial biases into the very fabric of urban life.

Surveillance capitalism in South Africa serves as a stark illustration of how data-driven technologies exploit racialized identities while reinforcing mechanisms of social control, particularly within university settings. This intersection of historical legacies of oppression with modern surveillance practices creates an environment where marginalized communities continue to face systemic inequities.

-

“Though Fees Must Fall originally appeared back in April 2015, mass protests against excessive student tuition fees and debt in South Africa are not a new phenomenon, as these protests have been on a steady rise ever since the country’s official transition to democracy in 1994.” These demonstrations escalated into violent clashes as police and the University of Witwatersrand’s security were deployed to forcibly prevent students from accessing the Great Hall. The situation intensified when members of the media were forcibly removed from public areas by campus security guards acting on orders from Wits management, who were concerned that media presence was “instigating and fueling” the protests.https://unicornriot.ninja/2023/feesmustfall-south-africas-student-movement-for-free-education/ ↩