From This Place

A conversation between Lukas Burkart (TEN), Daniel Ganz, and Shirana Shahbazi

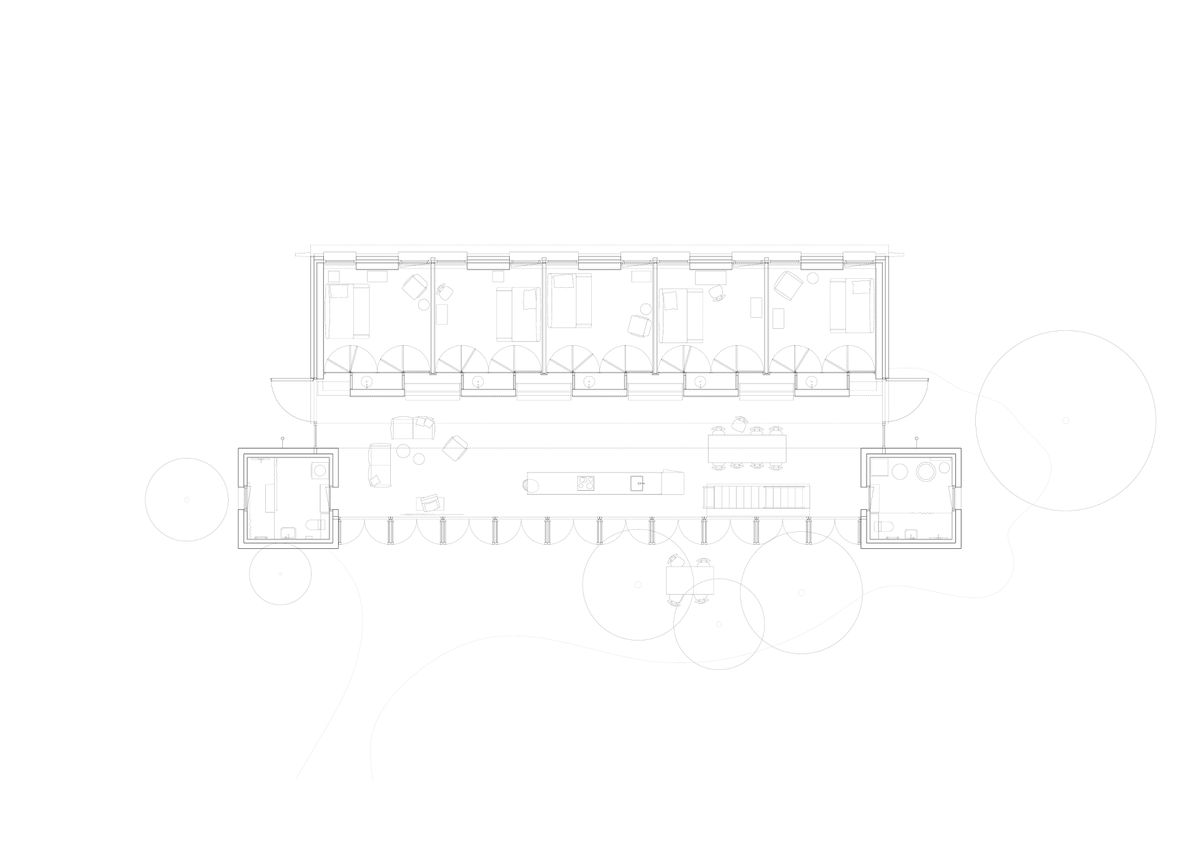

Lukas Burkhart, Daniel Ganz, and Shirana Shahbazi discuss their collaboration while working on the design and construction of a house for socially disadvantaged women in the countryside close to Gradačac, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- Lukas Burkhart

- I think we might begin with how the project came about, or how we came together. Daniel, if we start with you, how long have you been involved in the project?

- Daniel Ganz

- I can’t tell you exactly. Nemanja (Zimonjic of TEN) presented me with the project that you were planning. He described the place and it really fascinated me. I had tried to imagine it, as I had never been to Bosnia or to this region. He showed me a few photos of what it looks like there. Then he explained that you wanted to build a women’s shelter.

- Shirana Shahbazi

- I can remember, for me it was like this: first, we got to know each other from working together at ETH and so we already had a relationship where we would work together and help each other; then you came to me with this project.

While the building volume was already fixed in the design, you still approached me with a great deal of openness. The task was not precisely defined from the beginning to the end, and I think my strength is that I can also work in this way. A lot of things came out through the process.

We also had to develop the idea of what we wanted to do, what we can do, what makes sense, and what is financially possible. Now that the building is finished, the façade cladding has become an important part of its identity, so the choice of material was suddenly very clear, right?

- LB

- Yes, I think, earlier in the process, we had a model where the volume at the top was white, and we were never sure what we should actually do with the material and what the expression would be. Jelena (Perović) from our team suggested that the project needs more than we can offer alone, that someone else could take over the façade and the interior. The rest of the materials—the brick, the concrete—were raw, so we also imagined that certain things would remain a bit raw. Although, that has very different connotations in the Balkans than perhaps in Switzerland.

- SS

- It was important that Nemanja and Ognjen Krašna, being from the Balkans, were part of the team and could understand how the reading of this raw materiality might change in this context.

- LB

- Early in the project, we made a trip with Ogi (Ognjen) to Sarajevo.

- SS

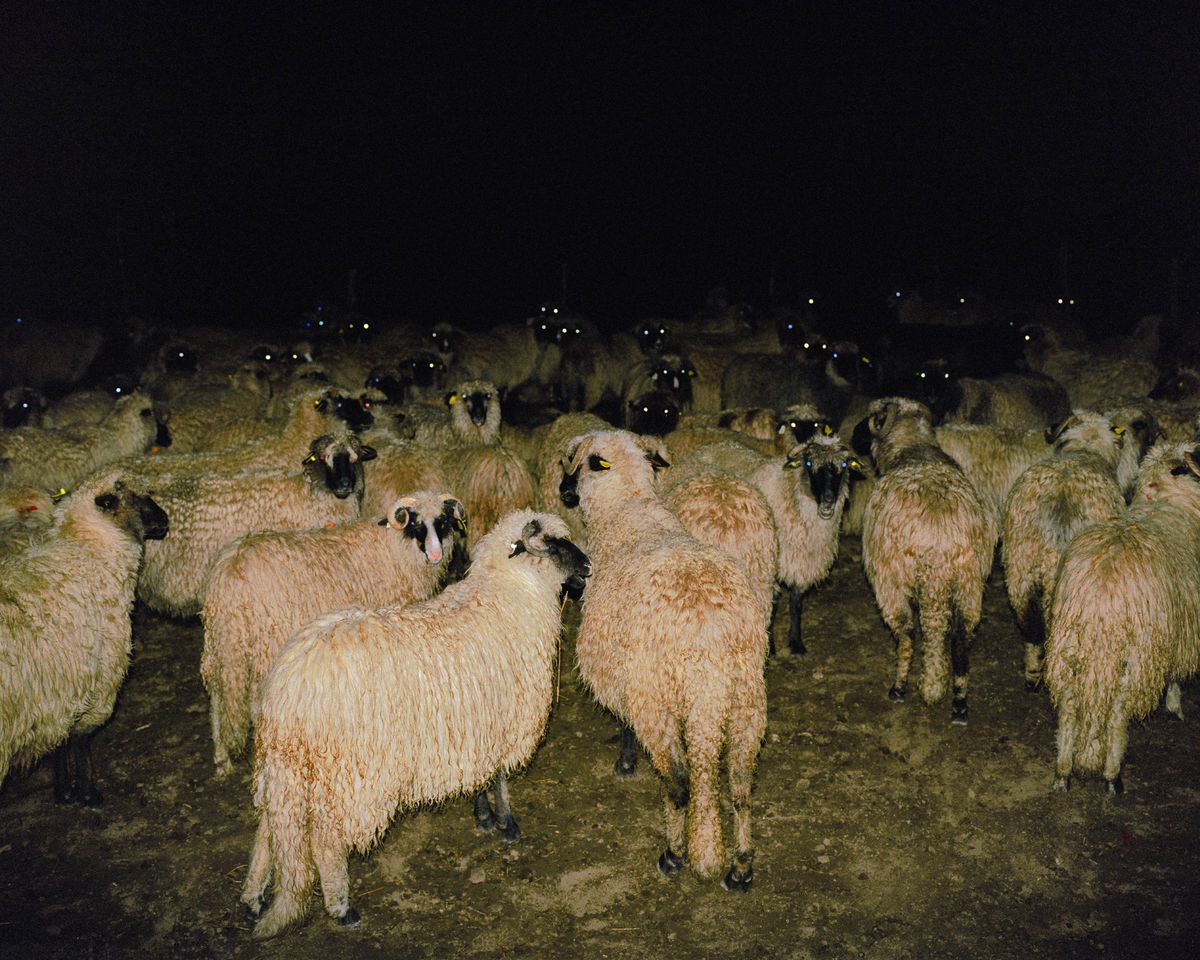

- We wanted to meet the women who produce textiles there. We wanted to see what is made in the surrounding area.

- LB

- We spoke to an organization that supports women who make textile crafts. Then we went to Gradačac to visit an old woman who stored the loom in her house downstairs.

- SS

- I had that in my hand today, that textile.

- LB

- We also went to the car paint shop - where we ended up producing the coloured façade panels in the end.

- SS

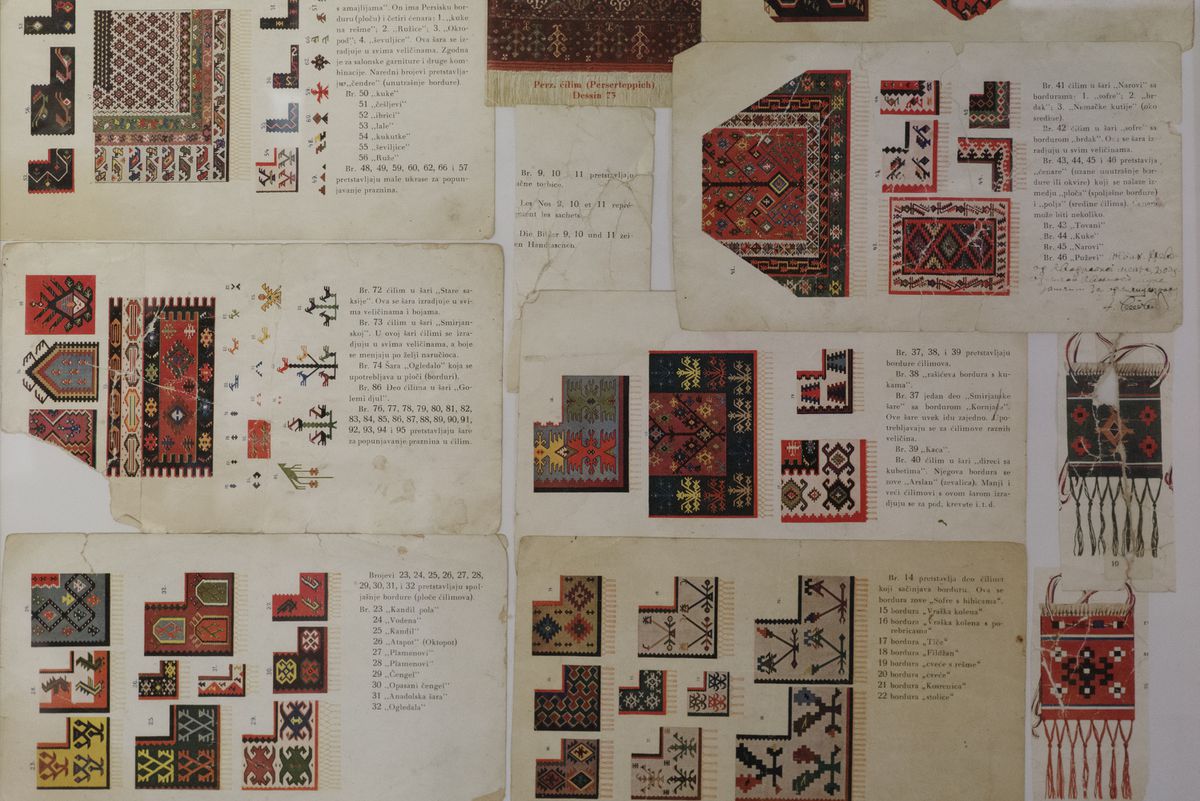

- And we also visited friends who collected Kilims (flat woven carpets). We scouted what was available locally. That’s where the idea for the façade cladding came from.

- LB

- I think it was also about everyday life, wasn’t it? About the everyday lives of women. I can still remember the pictures of Nura, who lived in the old people’s home, where you first considered the question of colour, which is very important in Bosnian culture. But also, the question of layers, right? Textiles over textiles. That was an important moment where we thought that perhaps we would do the first layer to show that it’s totally okay if new layers are added.

- SS

- The pictures of your journey to Sarajevo were important for us to see how people will live in the building. We had no idea how the design would develop, and we never said we were finished.

- LB

- We’re still not. The project needed this openness, from all sides, to develop into what it is now, or what it will become.

- SS

- And the continued work of Subhjia, the carer, and also that of the residents. The whole project is much more than just putting up the building. The community contributed in whichever way they could.

Also the panels we used for the façade were given to you for free, so the construction manager didn’t just purchase them. What was his name? - LB

- Senad.

- SS

- Exactly. And the raw panels had this wavy shape, a given width and surface structure. The white cube, the top volume of the house, was very long, a relatively unusual shape, and we wondered how to keep this architectural gesture and still somehow enliven it … and we used five colours that are actually the same size in terms of surface area, but not in terms of shape. For me, these were the small clues as to what rules of the game I should follow. Although it looks so wild, it was quite a puzzle to find a solution.

- LB

- I think the people who were often there on site during the construction, especially Ognjen, also noticed that the surface, because it’s completely shiny, meant that different colours are dominant depending on the weather and season. In winter, the surroundings are white, in summer it becomes a very lush green, and in autumn it’s brown again. Over the seasons, we developed a great fascination with how the house behaves. I don’t think you ever see it the same way.

- SS

- But as architects, would you have approached this project differently? It’s a great deal of freedom in this project to say, now we’re using this deep magenta. They are not typical colours in the Swiss context. When you come up with such a strong colour scheme, you’re sometimes afraid, but you have to consider how it exists in the environment, how it changes. It’s not like a slap in the face, but it lives with the context. I was also afraid of it, I have to say. We tried to make good, serious samples, but I kept wondering: hey, is it good?

- LB

- I was also unsure whether it was too much, even for the people there. In the end, it is also about how it is perceived in the village. But from what I’ve heard, the feedback has been very positive. I think it grows on you. I think everyone is proud. For us, it’s also about identity and visibility.

- DG

- Did the colours come from these carpet patterns or how did you come up with this colour selection? I also have the feeling that the positive reception has something to do with the fact that they use these colours in everyday life. Even these interiors, with the flowers, it has a tonality that feels familiar to me.

- SS

- Yes, definitely. We looked at a lot of pictures from the trip. It was all about finding a group of colours that looked like a family but were still individual protagonists.

- LB

- I mean, you work with colour often and I think you have a feeling of what a colour family could be to some extent. Once we had the samples, it happened quite quickly.

- LB

- Maybe we can discuss a little bit about when we first met as this group (Daniel, Shirana, Lukas), directly on site.

- DG

- So on a later trip, the four of us (Shirana, Daniel, Ognjen, Lukas) went there to select the trees. Ogi drove us there from Belgrade. On the way, we went to the nursery to see what kind of plants were there. We had a certain idea of what we needed. When we were at the nursery, we saw—or I thought—the range was rather limited. We walked through the nursery, looked for these few trees that we wanted and then, quite spontaneously, we chose the blackthorn (Prunus spinosa), well Shirana chose it.

- SS

- It just looked at me like that!

- DG

- We immediately thought, we have to find it a nice place for it. We did everything in one day—we chose it, then they dug it up.

- LB

- We got to the house, and we wanted to plant the trees, but they had started with the drainage at the same time.

- DG

- The site was full of trenches…

- SS

- Yes, they (the construction company) had just started digging [laughs].

- DG

- We waited for a very long time. And then, somehow, towards end of the day, we managed to at least define where each tree would go, and the gardeners then started planting.

- LB

- I remember Hazima Smajlović’s brother, Mustafa, told us where the good soil was, didn’t he? Or rather, Daniel asked him because they had no topsoil, they had only brought us sand.

- DG

- Exactly, because the place was very much a building site. And that’s right, Mustafa is a farmer and works the land next door, and he told us that we could get topsoil there because he had just ploughed the ground there.

- SS

- And even though I have no idea about plants, you still included me in the process.

- LB

- I think it was important that we considered the composition of the trees together with the façade, because it’s an interplay.

- DG

- And that’s actually the point—you can plan everything beautifully and then on site you realize that you have to take a closer look at it. It was so valuable when you as an artist, Shirana, and Lukas and Ognjen as architects, gave your opinion and so the right location could be found. It was really nice to work together like that.

- LB

- There was always a dialogue, wasn’t there? Even with Hazima, the team from Engineers Without Borders, and us, how the whole thing was organized. I think it was very important that we always had people on site to support us in the development. In the end, the project only works if it is actually anchored in place. This goal probably permeated everything. We always tried to develop it locally, in dialogue.

- SS

- I had the feeling during the project that everyone was on the same—not to sound esoteric—but the energy was the same. Even on our first trip, when we were at Subhjia’s house, together with your brother and Hazima.

- LB

- Even with Senad, the master builder. I think everyone had the same motivation.

- DG

- The most beautiful thing is really that something like this was created from this location with these people on site, from these materials on site. That’s what I find most fascinating about the whole thing. Of course, we have our idea that it was created from this place. And from the people who live there and live with it.

- LB

- We gave this project a lot of time. On the one hand it was a question of financing, which was not covered from the beginning—it was also a very big job for the Engineers Without Borders—but on the other hand we also gave a lot of our time for the people.

- SS

- It was the opposite of the profit optimization approach. It was never about efficiency—it was about an intelligent handling of circumstances, of means.

- DG

- And that can also be so beneficial, if you compare it with our typical way of working.

- LB

- Yes, in hindsight it’s the right thing to do. But it took a lot of perseverance.

- SS

- We went there and responded to the situation, but without the people on site, the thing wouldn’t have come to life… What makes us so happy is how the women live in the building—preserving jars, hanging carpets on the wall instead of on the floor, as we imagined—and Subhjia’s work to organize it.

That’s the beauty of this project, that it is revitalized from within. Everything that surprises us, everything that we haven’t thought of, that arises of its own accord, is what touches or inspires us. - LB

- That was also the case for us when working with you…We couldn’t imagine what it would look like in the end. We often discussed together that we wanted to hand over the authorship a little early on, so that it would remain open.

- SS

- I know. I checked you once or twice to see how open you were [laughs].

- LB

- It was very important to us that it was a collaborative effort, where there are no boundaries between us, you, or the people who live there now, or perhaps will live there in the future.

- LB

- We are interested in the question of how open or how finished architecture should actually be. I think with your work, Daniel, the landscape projects are only finished after…

- DG

- They are never really finished.

- LB

- Well, yes, they only really come to life after five years perhaps. That is quite different to the typical understanding of architecture. You often hand over the building and then of course it’s not finished, but not so much happens once it’s built. Then you open the building, and you just repair the mistakes, so to speak. Whereas I believe that we will continue to accompany this project.

Maybe in art, too—Shirana, are your works finished when you hand them over? - SS

- The so-called finished form of my work—for example, work in an exhibition—is the state that is most alien to me. It’s always just a moment where you hold still and then you move on. Sometimes you grow apart a little and then you leave some things as they are. Daniel, you can’t do that with your trees.

- DG

- That would be mean. The trees are always calling us. We’re interested in that too, because we want to know, are the trees growing now? Does it have the shape we want? Or has there been a storm in the meantime? Or a lot of snow, for example? As is the case with the blackthorn mentioned earlier, where the snow has broken off the tree’s branches. It will sprout again and look for a new shape.

- SS

- It will come back. And then we’ll go and prune together.

- DG

- A gentle pruning.

- LB

- Perhaps, so that this conversation continues beyond us, is there anything that you would you like to know about Subhjia, the residents, Hazima, or Ogi?

- DG

- I certainly have a few questions. I’d be interested to know how the trees are doing, how the walnut tree or how the garden is developing. We have planned a garden to cultivate vegetables and flowers. I would also be very interested in that. That would be one question. Or whether they have built the well or whether that is still to come.

Then I would also be interested in the utilization. I’ve seen that they’ve put a table there with a parasol. The idea would be that, eventually, the maple tree is so big that the shade comes from it. I’d be interested to know how that feels to sit outside there.

- SS

- Well, I would also be very interested to know how this way of life feels for the women. It’s a new experience for them, coming together with four other women and living in these small units and the large, shared space. I don’t know if it would be a typical way of life. I would be very interested to hear what the residents have to say about it. When I look at the exterior, the details of the furnishings and so on, it seems very homely to me. I would also like to know how the project is perceived in the village.

- LB

- I think you can see a great deal of care and love in the house. That’s what makes us happy.

- SS

- The whole project stems from this violent history, for all the protagonists, and it has to be said that the architects are from Serbia and the house is in Bosnia. However, the project is not a poster child for international understanding. I would like to know what does it mean to Hazima that the project has come as far as she imagined it would?

And a question for you Lukas, is it okay if they continue working on the building? Would you also be okay if the volume was changed? - LB

- I think so, yes. We are actually very open with our projects. The house in Belgrade (Avala House), that we looked at together, also lives on with us. I think it’s nice when there’s a dialogue about what’s happening, but we don’t need complete control either. We are interested in how people interpret something, what they do with it.

I think we will gradually try to work with them on different levels, perhaps just as consultants, or perhaps we will draw something one day. We are very open to making it work for everyone.

At the very beginning, we didn’t know who was going to live there. It was a house that was only intended for older women, but we also speculated that it would be a bit more mixed, that there would be younger women and maybe even families. Now, four of the rooms are permanently occupied and one is open for emergencies. I think that has already proven very successful.

It was important to us that the design was simple enough to allow for something that we hadn’t previously planned. I think we are also interested in where it can be improved. Perhaps, this is not a finished job. - SS

- Yes, let’s keep up the good work.

- DG

- Exactly.