Environmental Histories of Architecture

An Introduction by Kim Förster

The environment, more specifically what practitioners, historians, and theorists of architecture understand by that term, is in flux—its definition is contested and expanded as society’s relationship with nature changes. Based on an open call launched in 2017—a moment when the wholesale modification of the Earth was becoming undeniable—the CCA began working with a group of researchers on a multidisciplinary research project sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s Architecture, Urbanism, and the Humanities-Initiative. Over the course of eighteen-months, the team interrogated what it means to write an environmental history, or rather multiple environmental histories, of architecture.

Though the project was already in conception, the urgency of the topic became evident following the UN Climate Change Conference in December 2015, which placed the accelerating climate crisis and its consequences on the political agenda of the international community. As a result, architecture, both as a discipline and in its practical application, was increasingly implicated in contributions toward the Paris Agreement, to limit the rise of global temperature rise to 1.5°C. Moreover, in August 2016 the Anthropocene Working Group of the Geological Society of London recommended that the Anthropocene be considered a new epoch in which humans are the critical and decisive geological and biological factor of change on Earth. This provided another framework for research into explanatory and interpretative patterns for managing the challenges and risks humankind is facing. There remain, however, general objections in discourse to the validity and scope of the Anthropocene, to the implication that “Anthropos” subsumes all human activity, and to the reproduction of a white, Western, male perspective. Under the working title Architecture and/for the Environment, the multidisciplinary research project started from the hypothesis that the built and the natural environments are co-produced and with the intention to move research beyond purely pragmatic, techno-utopian, or even environmentalist stances.

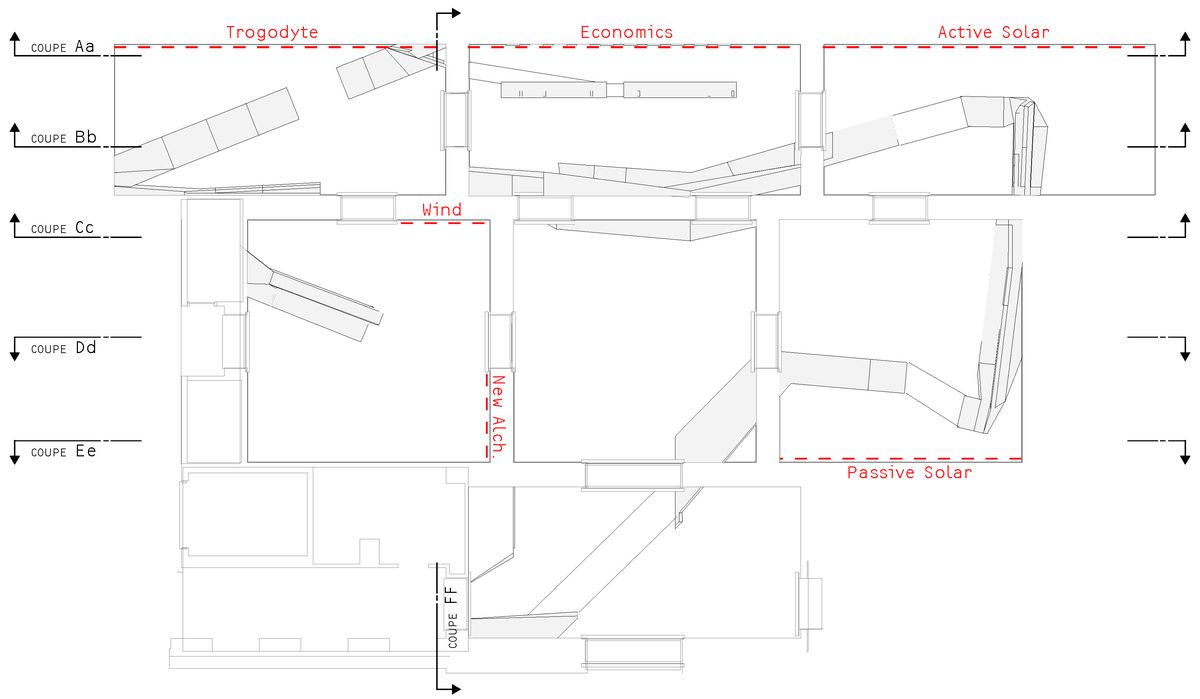

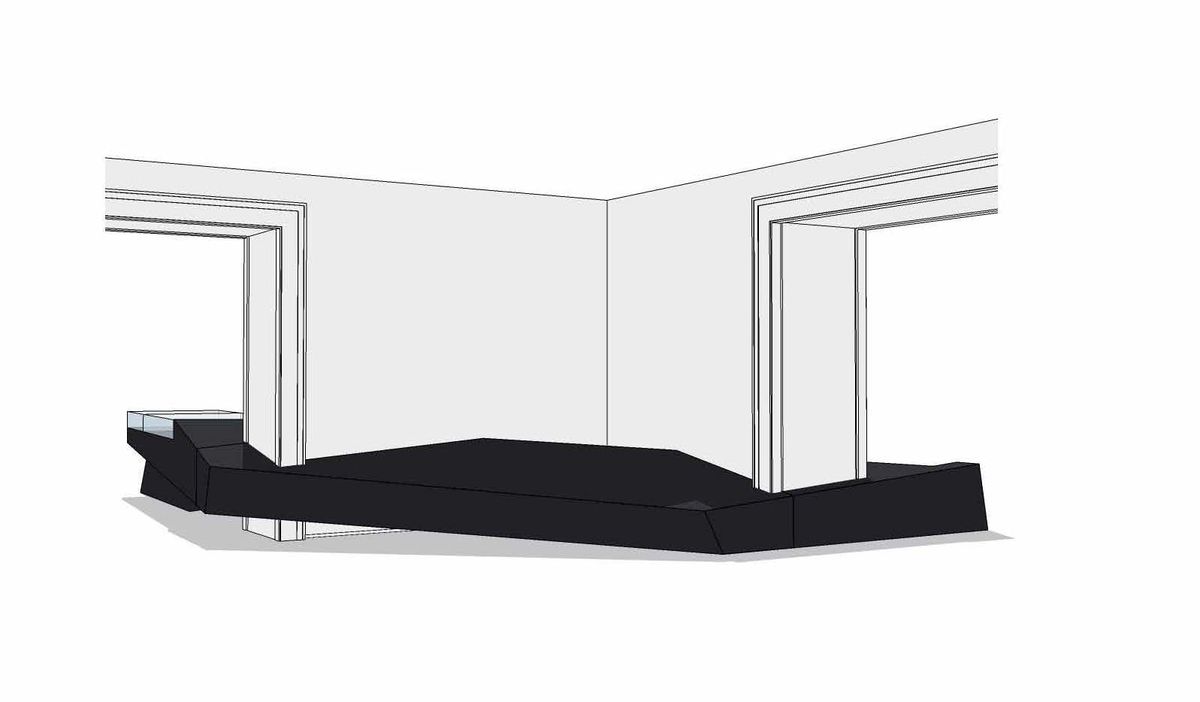

An integral part of the exhibition design by Saucier + Perrotte Architectes for 1973: Sorry, Out of Gas (2007–2008) was a black structure winding through the galleries that alluded to the flow of oil in a pipeline. If the proposal had been realized, the structure would have appeared to puncture the CCA façade. Since then, oil, politics, and culture have been studied in the energy humanities and in architectural history in relation to the ideas of petroculture and petromodernity.

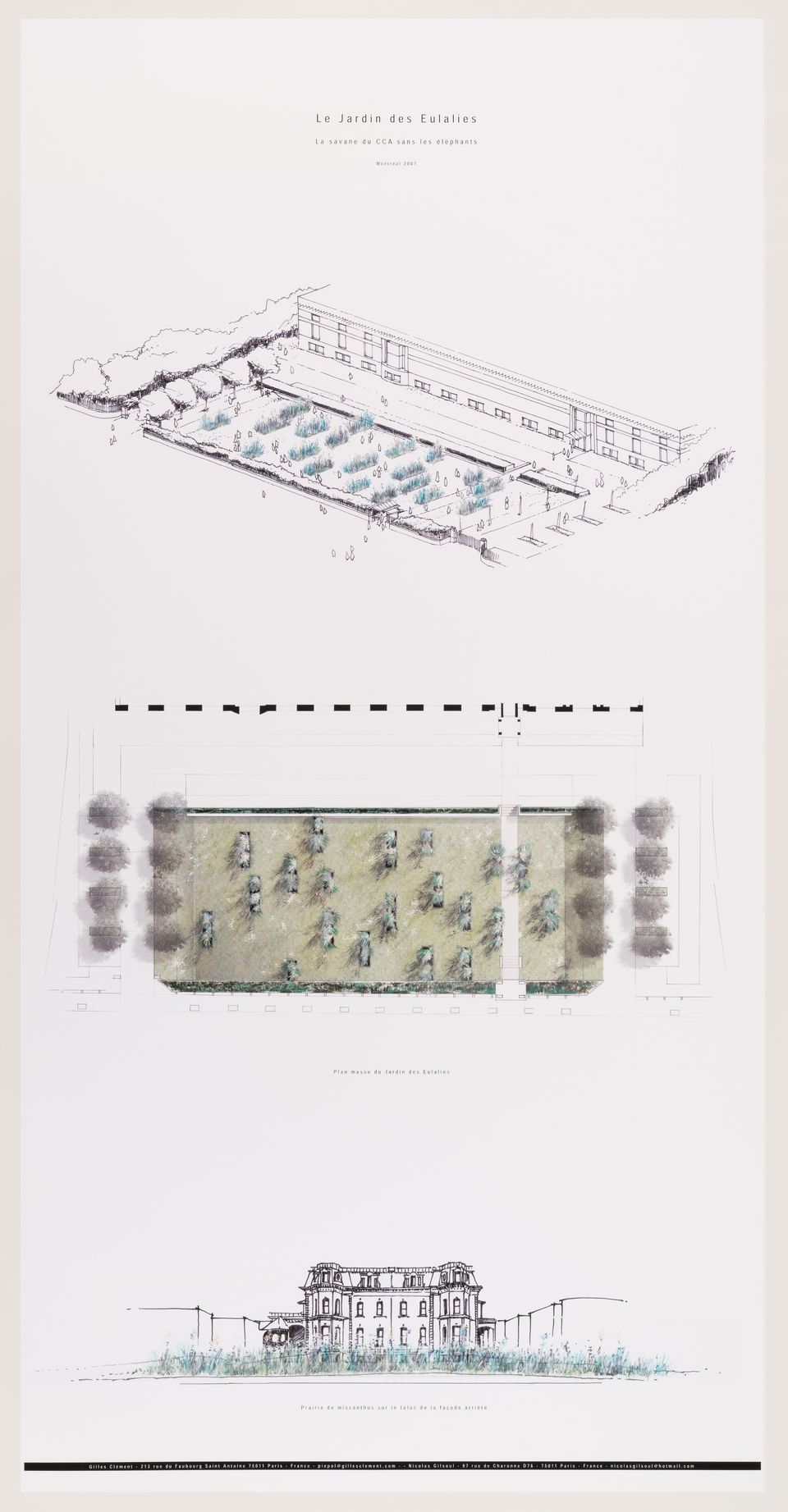

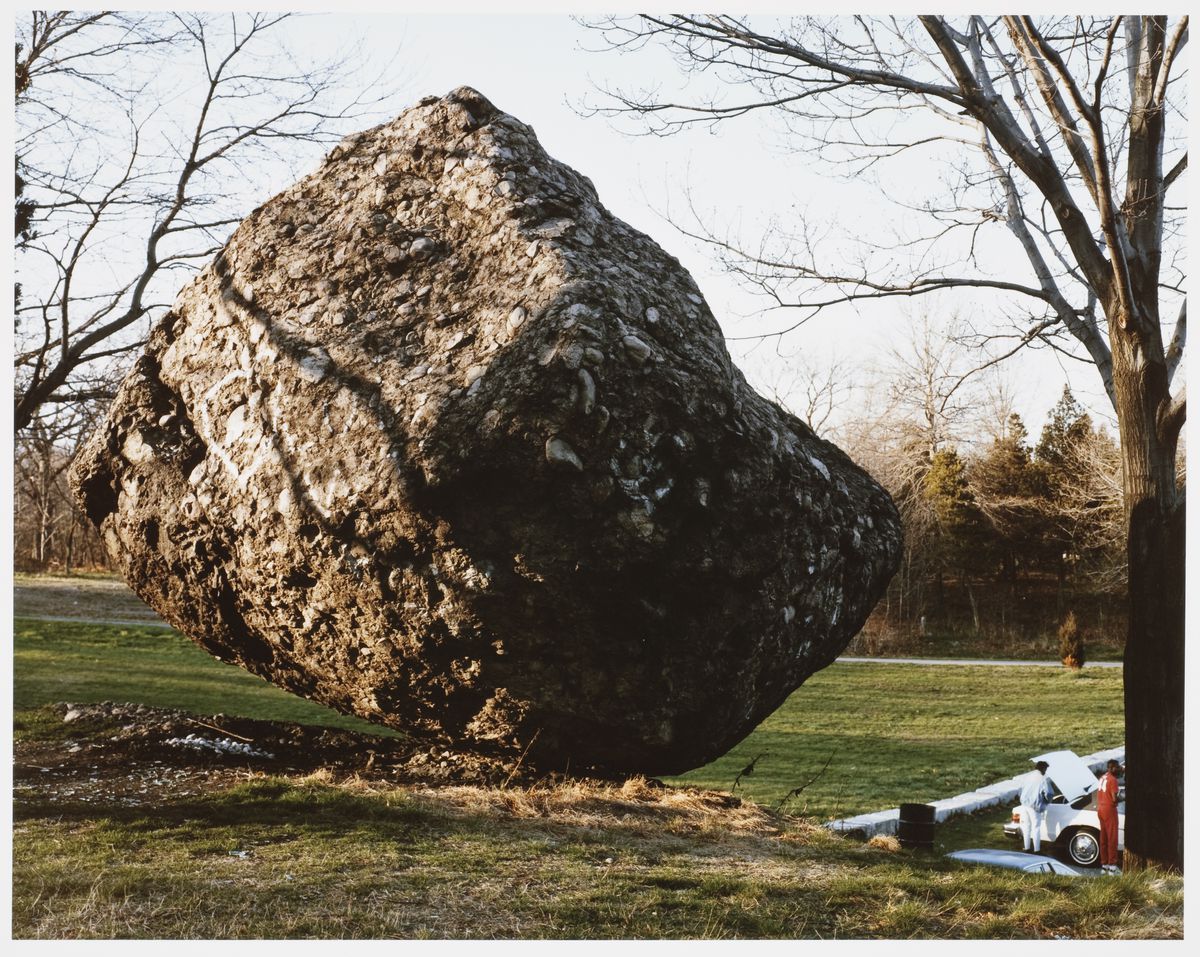

The CCA was an ideal setting for this research because it provided the structure to operate at the intersection of academic, cultural, and professional sectors, allowing research to be both critical and operative in its concepts, goals, and methods. The topic also built on two previous CCA exhibition and publication projects, which both positioned the environment as a battleground for broader social, political, economic, and ultimately cultural concerns. The first, 1973: Sorry, Out of Gas (2007), showcased architecture’s response to the oil shock of the 1970s, the genesis of postmodern solar and eco-houses and their precursors, and the political construction of the energy crisis. Nearly ten years later, It’s All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment (2016) marked Canada’s 150th anniversary by offering counter-narratives to modernity’s promises of growth and progress, illustrated with twentieth-century cases of climate change, extinction, and extraction, as well as settler colonialism. These projects generated others, including the colloquium Sustainable?, which scrutinized architectural practice itself; the web issue The Planet Is the Client, featuring collection material acquired as part of the two exhibitions and individual research on them; and Goodbye, Oil, an illustrated book for all ages of ideas for living without oil. With these investigations, the CCA was already complicating architectural history of the causes and effects of environmental relations, by considering energy issues contextually and relationally and by acknowledging that the concept of environment cannot be reduced to a romantic, idealized image of landscape or nature. And yet, this work was still framed from the perspective of the Global North, even as changes due to global heating were already occurring unevenly around the world.

The prospect of various tipping points that would move the planet toward a climate and biodiversity crisis required a global, indeed planetary, perspective of history. To address architecture’s complicity with these accelerating risks, Architecture and/for the Environment was conceived of as a historiographic and epistemological research on the discipline’s entanglements with environment and its use, abuse, and destruction of nature—giving rise to subnature, to adopt David Gissen’s term. By foregrounding an environmental histories approach from the outset, the project left environmentalism and the ecological turn of the 1960s and 1970s out of its research scope (while acknowledging that this history had already been set aside by other agendas and topics since). Instead, it built on a critique of growth paradigms of twentieth-century architecture, such as those of obsolescence and sustainability explored by architectural historian Daniel Abramson. Another key reference for critically engaging with such entanglements was cultural theorist Imre Szeman’s critical studies on petrocultures and petromodernity.

Such positions in the architectural humanities, and the humanities at large, informed the objectives of the research project. One was to acknowledge architecture’s dependence on fossil fuels by focusing on material and visual culture and on design and technology (and by not overlooking energy intensive and highly emissive building materials and their circulation). Another was to overcome outdated thinking and behaviour—notably that associated with the dualism of human and nature—in favour of practicing what eco-feminist scholar Donna Haraway and sociologist Bruno Latour called natureculture. The project argued that architectural and environmental discourse must expand beyond the limited frameworks of energy and climate change and that a curatorial approach provided the necessary framework to initiate new directions in architectural research and teaching.

While the open call for researchers already highlighted the invention of the environment in architecture, it was architectural history itself that would be scrutinized, to understand what history of the environment was already written and which other histories needed to be told. This historical revision and strategic redirection seemed necessary, given that both the architectural profession and research and teaching of architectural history has defined and legitimized architecture’s relationship to the environment as part of the modern project. The eight researchers—a unique group selected through a peer review process guided by Gissen and Abramson—were therefore encouraged, individually and as a group, to develop globally diverse histories of architecture through the lens of the environment, and vice versa, and to bring those stories into dialogue.

The researchers initially focused on identifying overlaps and differences—in their topics and priorities, periodizations and chronologies, geographies and scales, as well as their values, attitudes, and beliefs—before adopting individual methods, principles, and techniques of academic and cultural research and production. The CCA encouraged a range of social and environmental topics within architecture, all to varying degrees connected to the history of global capitalism. In the end, these include the early cultural objectification of coal; the notion of urban nature itself as pollutant; the dominance of oil and new patterns of energy consumption in architecture; the blind faith in technology to control environment; the cooperation of science, industry, and policy in shaping thermal comfort; the exploitation, geopolitics, and marketing of asbestos for housing; the agency of architecture in facilitating human-animal cohabitation; and finally the architectural implications of ethnobotanical knowledge for tracing human-plant relations.

From fall 2017 to winter 2019, the researchers pursued their individual projects through archival visits to the CCA and other institutions, interviews, or field work. The collective work of Architecture and/for the Environment was structured by three multi-day workshops, two in Montréal and one in New York City, the latter two accompanied by public events. These were key moments for the joint production and exchange of knowledge. While the first workshop at the CCA in November 2017 was for the researchers to find common ground, collect terms, define references, set goals, and address challenges, the second workshop in June 2018, entitled It’s Complicated, promoted multidisciplinary exchange to build on the individual analyses and arguments. The event was framed by the conceptual pairings of Energy/Power, Control/Systems, Body/Exposure, and Post-Human/Nature, each explored through a conversation between two researchers and an invited scholar—respectively, Dominic Boyer, Michael Osman, Gabrielle Hecht, and Etienne Turpin. The workshop called for nothing less than a historical and theoretical re-evaluation of architecture as a central measure of scale, framed by current concerns within environmental and energy humanities.

Finally, the third workshop in New York City in October 2018 was hosted with the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University, local organizer Jacob Moore, and moderators Meredith TenHoor and Reinhold Martin. Under the title It’s Simple, the researchers presented methods for producing evidence and building narratives, while addressing the prompt of the workshop: How can environmental histories of architecture acknowledge the winners and losers of the Great Acceleration of mid-twentieth-century America and the Great Divergence of the twenty-first century worldwide? While the threat of global socio-ecological collapse—tracked, for example, by reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—continued to be brought to the researchers’ attention, the goal of Architecture and/for the Environment was to offer far more than a history of the last two centuries or a diagnosis of the present. Rather than propagating an eco-modernist optimism or reinforcing a fear of apocalyptic scenarios, the historiographic and epistemological diversity and scope of the project—individual explorations, interdisciplinary workshops, and collaborative research—offers a new form of environmental history that holds architectural practice, history, and theory accountable.

A reading list compiled by the researchers of Architecture and/for the Environment, which became an “Environmental Histories” bookshelf in the CCA Study room for the duration of the project. Download PDF here.

This resulting publication, Environmental Histories of Architecture, presents the work of eight researchers who each analyze specific environmental relations, crises, and reforms and demonstrate how society and the environment have been co-constructed, represented, and lived in their respective geographies. While their essays are published independently as chapters (each available for download via the link above), together they cover an expansive range of thinking about how the environment changed, and was changed by, architecture.

Aleksandr Bierig studies the London Coal Exchange, a building that opened in 1849 to house a market where the city’s coal was traded but not distributed. By taking the Exchange as artefact, Bierig examines the moment when coal became a thing—a commodity—and offers an architectural perspective on fossil-fuel history. He draws on a literary analysis of extraction and labour in the mines and an architectural analysis of the display of plant fossils in the Exchange to outline a profound moment in the development of coal’s social and cultural significance. The building’s spatial reach and material expression suggested that fossil-fuel use had begun to unsettle the relationship between human history and geological time, raising haunting questions regarding “ghost acres” that remain with us today.

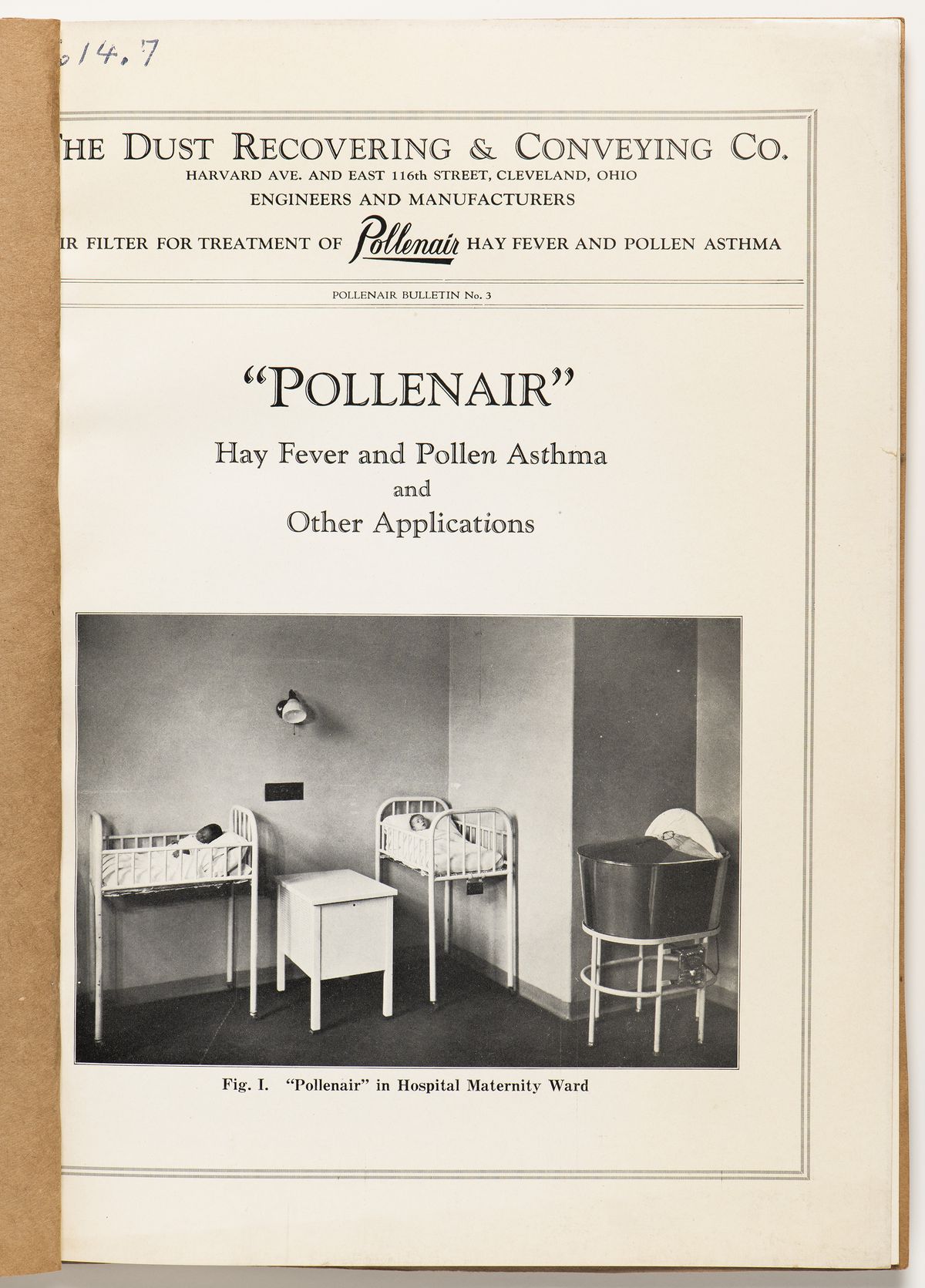

Nerea Calvillo explores what happens when nature itself, in this case pollen, is deemed a problem, even a pollutant. The essay introduces the pioneering women of Hull-House, a reformist settlement project founded in Chicago in 1889, who conducted extensive socioeconomic surveys that mapped—at least implicitly—the distribution of ragweed in the city, before pollen-induced hay fever had been medicalized and commodified in the United States. Calvillo draws on ecofeminist literature to shape a queer theory of pollution, one that addresses it beyond the architectural scale. Rather than simply revealing and representing pollen as pollution, Calvillo’s focus on the multiscalar politicization of urban ecologies allows for research into practices that intervene in society and nature, care for urban spaces, and are critical of neoliberal greening.

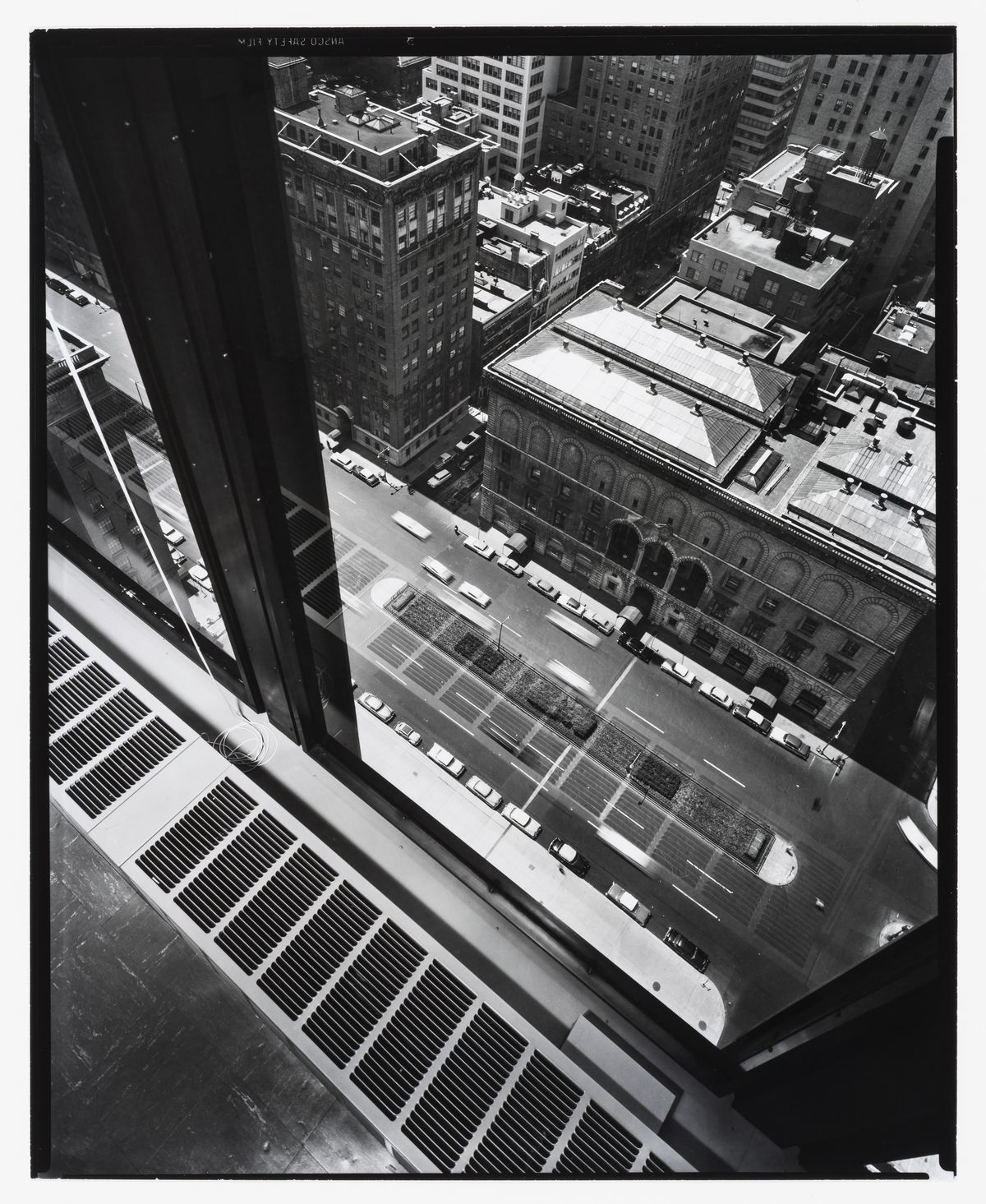

Daniel Barber renders oil (as used to heat and cool sealed interiors) visible in postwar North American architecture by drawing on analyses of petroculture, particularly the road novel as well as other literature, art, and film. Barber uses the Seagram Building in New York (1957) and the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris (1958) to demonstrate how the International Style created buildings that as cultural object and technical systems explicitly relied—for their functionality and aesthetics—on cheap energy, concealed in their façades, floors, and ceilings. Relative to current claims for future energy transition, Barber argues, among others, that the solar alternatives propagated since the 1970s must be studied against the backdrop of scarcity and of today’s petroleum-centred society and economy.

Kiel Moe argues that throughout the twentieth century, pedagogy in schools of architecture across North America constructed and maintained a bleak image of the environment as the very source of proprietary equipment. The essay traces this tradition from early curricula and textbooks, through course standardization and accreditation criteria, to the “Environmental Control System“ courses of the 1960s, which adopted the closed-systems thinking popularized by NASA as well as Reyner Banham’s take on mechanical services. Despite pedagogical alternatives offered by Lewis Mumford, James Marston Fitch, and Douglas Haskell, the focus on equipment was reinforced through close ties between industry and academia, leading to a path dependency that continues to dominate architecture curricula in North America.

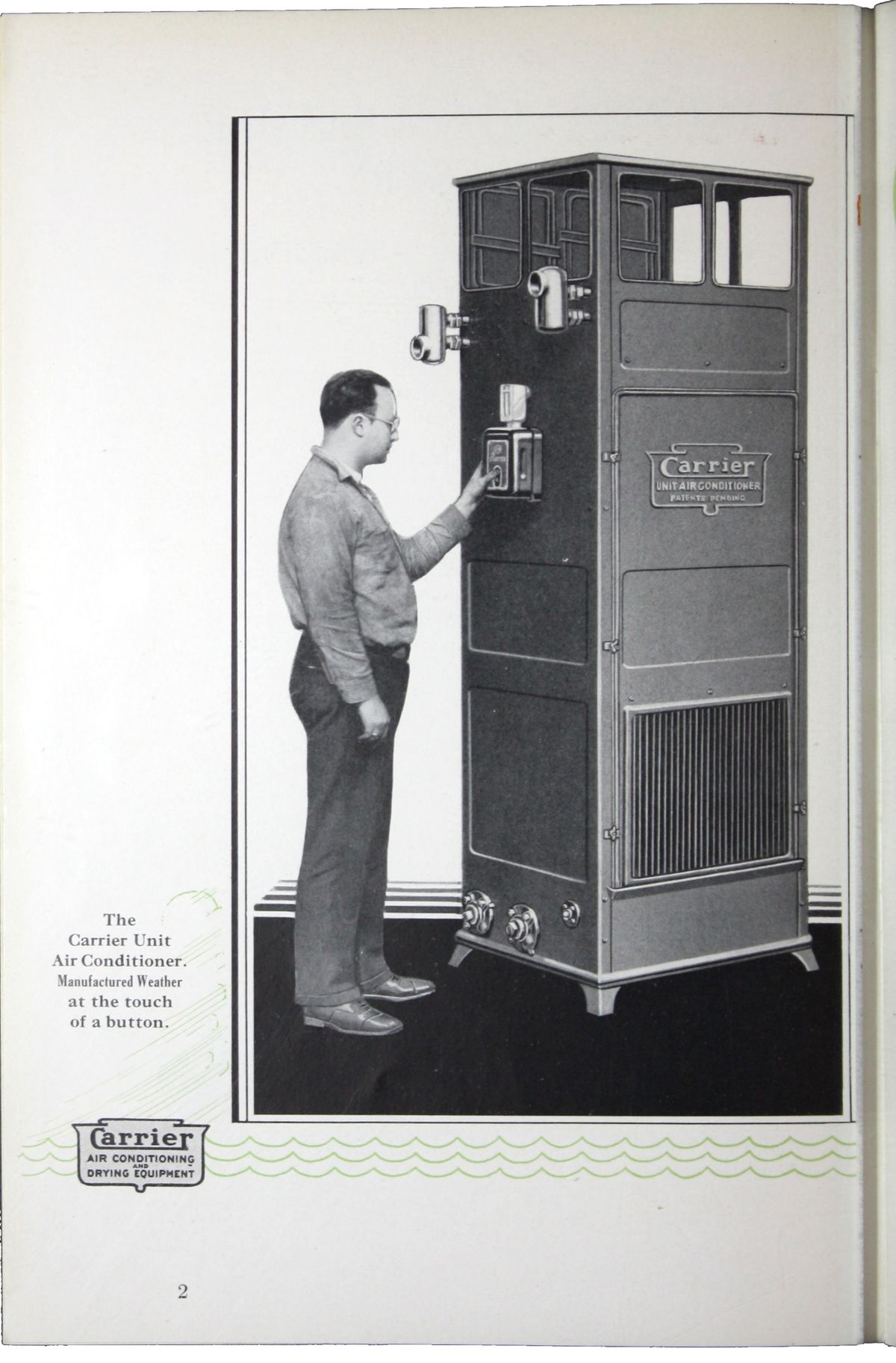

Jiat-Hwee Chang reconstructs how the air-conditioning industry originated in North America and became such a transformative force in twentieth-century architecture, while also critiquing the industry’s simplistic assumption of a universal standard of thermal comfort. In an effort to construct a more global history, the essay presents two sites, Singapore and Doha, Qatar, as examples of the proliferation of air-conditioned complexes in the Global South in the 1970s and 1980s, that were equipped by American firms or at least drew on American expertise. And yet, Chang explores recent projects to show that, in response to tropical and subtropical warming, these two affluent countries are actually producing hybrid cooling strategies for buildings and public spaces that blend technology and tradition, thereby challenging the air-conditioning dependency.

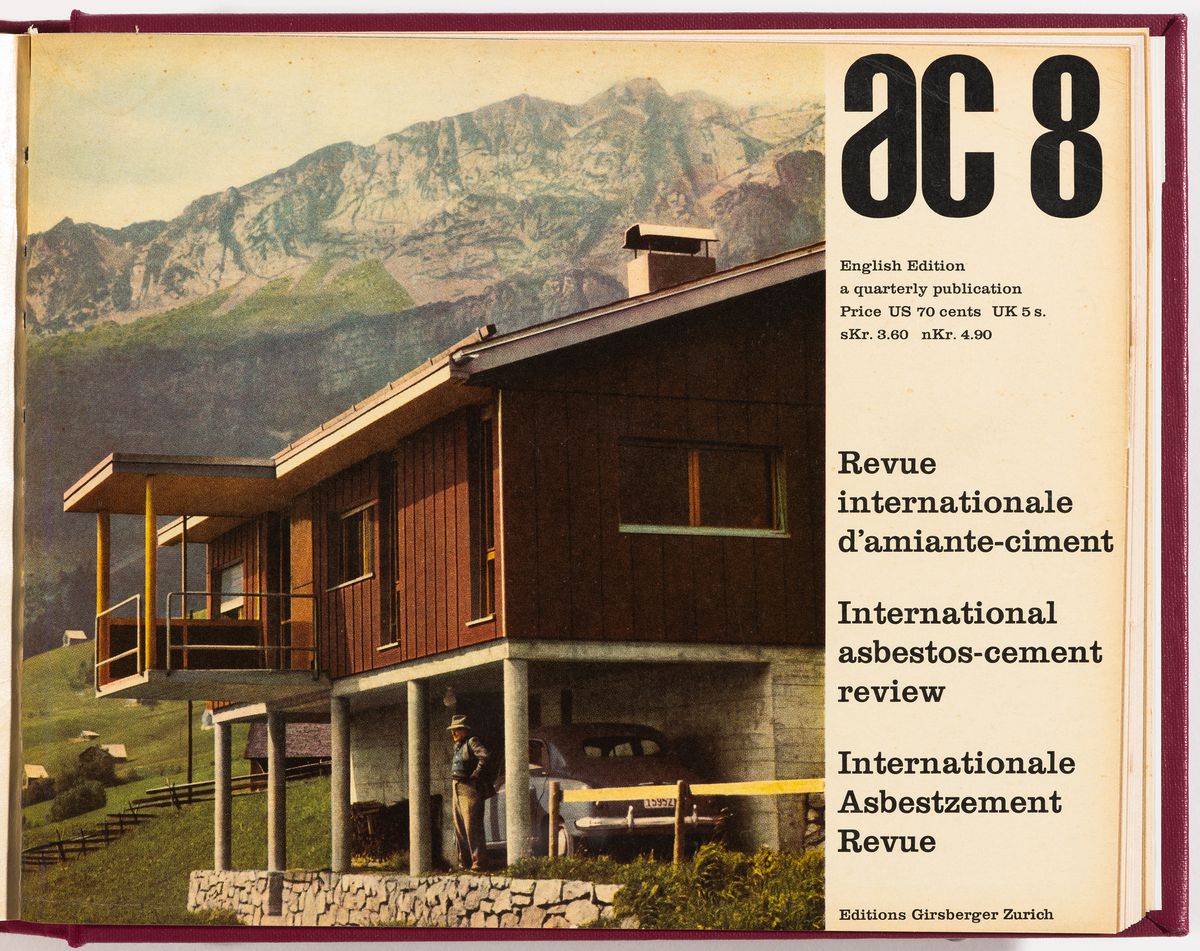

Hannah le Roux follows the material flows and corporate geographies of asbestos-cement, a construction material that proliferated globally in the twentieth century. The essay reveals the industrial, academic, professional, and political links between modernity and toxicity: le Roux traces how the Swiss-based multinational Eternit marketed its asbestos products from the 1950s on through the company magazine ac: International asbestos-cement review; how architectural historian Sigfried Giedion placed himself at the service of industry by writing for ac review and by using asbestos-cement in his own home; and how, through the efforts of the United Nations, the material became widespread in the Global South through prefabricated housing. Even after bans in many countries, the lingering presence of asbestos-cement is a form of “slow violence” that suggests the need for a “slower science.”

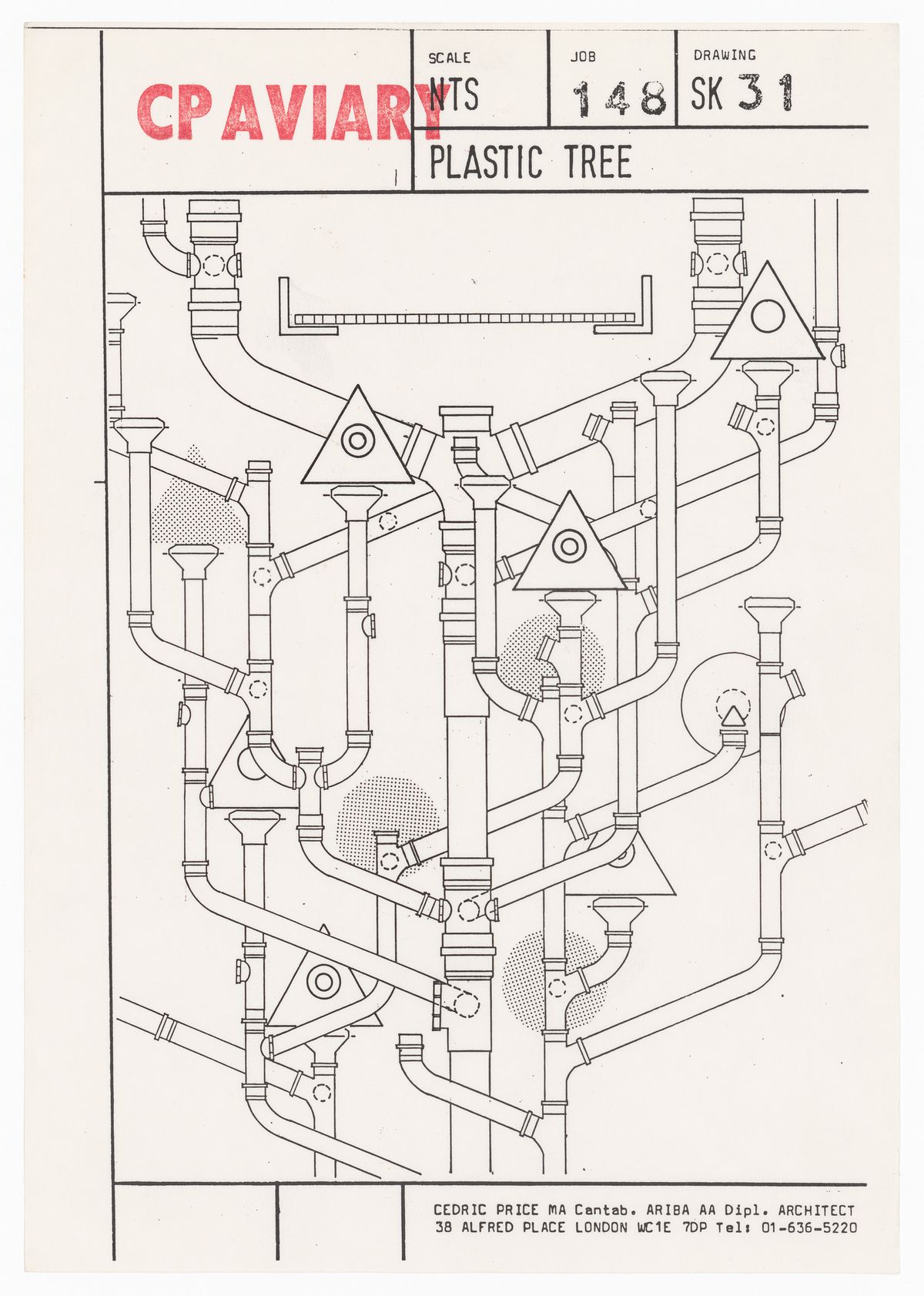

Isabelle Doucet takes two projects, the Cedric Price Aviary and related Funding Appeal (1981–1984) in London, United Kingdom, and Ant Farm’s Dolphin Embassy (1976) in Australia, as two contextual and self-reflexive case studies of possible human-animal relationships. The essay adopts an environmental humanities perspective to conduct an architectural analysis. In doing so, it asserts that even though both projects were ultimately unrealized and architecture was central in their proposed spaces for research and encounter, other tools and mediators were deemed necessary for them to succeed as multispecies encounters. Engaging with the storytelling methods adopted in these projects, Doucet offers a tale of architecture that acknowledges the meaningful lives of others—humans and non-humans—and facilitates multispecies survival and coexistence.

Paulo Tavares develops a postcolonial critique of the palm house and colonial-era plantations to frame an excavation of the ethno-botanical archive of American anthropologist William Balée. During an interview, Tavares and Balée discuss the plant diversity and formations in the Amazon region, documented by the latter in the 1980s. Through a research-based approach, Tavares challenges how institutions, both in the natural sciences and architecture, should build their archival collections. This critique is set within the context of Brazilian development policies that destroy Indigenous habitats and cultures with the backing of states and corporations that profit from rainforest deforestation—a crime against humanity and the environment.

These essays constitute eight episodes of environmental histories of architecture in the making. Beginning with the emergence of industrial capitalism and the new marketplaces of a fossil economy in nineteenth-century England, the series then broadly engages with the urbanization, modernization, and colonization of nature in the early twentieth century; the industrialization of construction and the socio-ecological trends in building materials, processes, and technologies in postwar North America; and finally the societal and environmental changes caused by the globalization and neoliberalization of economy and culture. The final essay, authored by me, offers a survey to situate the series within other larger currents, notably the interpretation and storytelling of environmental history and the environmental humanities; the material history that binds architecture and the environment together beyond energy and climate change; and critical, posthuman approaches to nature.

The knowledge produced through Architecture and/for the Environment, and released as an open-access, digital publication, contributes to both the field of architecture and to the call in the humanities for a historical and contemporary understanding of the environment in two ways: First, the project makes architectural history itself—its concepts and methods, agency and politics—the subject of inquiry in an interdisciplinary dialogue between practitioners and scholars of the architectural humanities, as well as, among others, anthropologists, historians, and philosophers. Second, the project goes beyond previous and parallel discussions about the historicization and the theorization of environmental issues in architecture, and especially in architectural pedagogy, by tackling global and imperial histories and trajectories of energy and material flows.

Of course, the CCA and the collaborating researchers were not alone in their concern for and critique of architecture’s problematic relationship to the environment—other work already existed or was unfolding at the time including, for example, Architecture in the Anthropocene (Open Humanities Press, 2014); Climates. Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City/Lars Müller, 2016); or a collaboratively written essay by the Architecture and the Environment interest group of the European Architectural History Network (EAHN) (Architectural Histories, 2018). And since the project finished, a variety of initiatives, publications, and institutions in architecture and the humanities have been formed to better understand and change environmental relations.

Yet the CCA, which perpetually questions the classical tasks of a museum and archive, has remained a productive setting for critically engaging with architectural history and for allowing research to develop through more open-ended forms of storytelling. It is because of the multidisciplinary, if not transdisciplinary, approach to and structure of Architecture and/for the Environment that the works presented in this publication offer not one, but multiple historical rereadings and reconceptions of the environmental relations of architecture. They do so by transcending the traditional separation of historiography as either critical or operative, thereby providing insight into present socio-political realities and offering clues for how to reframe through the environment the thinking and practices that underpin a possible future. Environmental Histories of Architecture invites readers to unlearn and relearn in order to envision a different relationship between society and the environment, between culture and nature, and to eventually decarbonize and decolonize architectural knowledge and practice.