Health Governance and Responsive Architectures

Text by Hilary Sample

Modern cities and their architecture have largely developed as a result of man-made rules and regulations associated with maintaining the public’s health.1 The evolution of these rules, particularly as they pertain to protecting collective health during unexpected disease outbreaks or epidemics, challenges the order and freedoms such rules were to uphold.2 In turn, rules for urban development have thus been shaped by the effects of both chronic and communicable disease events. Modern history has shown that the greatest disturbance to the urban status quo occurs during communicable disease outbreaks, in part because the speed by which disease spreads results in the destabilization of public space and life-sustaining infrastructures.3 Modern epidemics from typhoid, tuberculosis, cholera, influenza, polio, and Legionnaire’s disease to the more recent HIV/AIDS as well as SARS, Avian flu, and H1N1 viruses have each affected the cities they surfaced in, causing spatial guidelines to be reworked—and have since led to reforms of the built environment.4 Today’s epidemics are increasingly unpredictable due to never before seen anomalies in viruses and new superbugs. If rules and regulations are to provide a means of treating the built environment, urban health crises quickly upend those rules and undo established freedoms. To understand how these design conventions are thwarted in extreme cases, it is productive to examine the physical change to cities that is brought about by contemporary urban epidemics.

At any given moment, there are always at least two cities within any one city: a healthy city and a sick city. This innate division is most evident when a public health crisis occurs. Not only is a physical distinction between healthy and afflicted individuals recognizable by bodily appearance—consider the wearers of face masks during the 2003 SARS outbreaks or the withering forms of AIDS patients who came to media attention at the beginning of the HIV/AIDS crisis—but it is also possible to see physical repercussions of illness in the public body mirrored in the city’s architecture and its public spaces. Epidemics affect the ways in which cities and their buildings perform; having been designed, built, organized, controlled, and maintained according to policies, plans, and protocols formed before any contemporary epidemic could be predicted. In the face of crisis—such as the 2003 SARS outbreaks—a normally functioning city is drastically altered and subsequently controlled via entirely new and unexpected urban conditions; for example, the forced closure of hospitals, the emptying of street cars and subways due to voluntary quarantines, or the shuttering of bath houses at the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. These unpredictable and disruptive physical changes to urban space produce a greater distinction between the healthy and the sick. The urban transformations that occurred during SARS were first conducted on the scale of a single building. Small shifts associated with a building’s function can radically change its performance, that building’s subsequent performance on a block, the block on a larger urban area, and eventually the reconfiguring of the city as a whole. The city’s image thus becomes recalibrated from the inside out—one recalls the collapse of Toronto’s tourism industry due to the outbreaks. During SARS, the most visible changes took place in building typologies with a direct impact on health cure or care.

Unlike HIV/AIDS, the SARS coronavirus is visible under a microscope and was both discovered and identified with “unprecedented speed.”5 In comparison, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) took much longer to identify, and resulted in one of the worst modern pandemics. The collaboration of independent laboratories around the world under the leadership of the World Health Organization (WHO) provided an efficient infrastructure to rapidly decode the SARS virus. Although the success of containing the virus so quickly was attributed to the strong intervention of the WHO, there were controversial moments when the WHO opposed the authority of local, regional, and federal governments, enforcing travel bans and restrictions for weeks at a time to further exacerbate failing economic conditions. What the SARS outbreaks revealed is that health is no longer a local, regional, or federal concern, but a global one. Anyone anywhere can be infected, and regulatory practices and governance may not only be local or national.

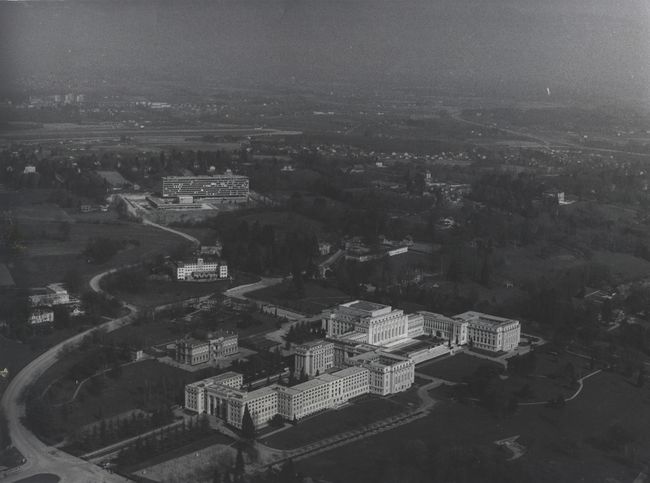

This is only half of the story of the WHO, for in fact, world health governance associated with communicable diseases has been organized since 1948 from a headquarters in Geneva. Today, the WHO is dedicated to the governance of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and TB.6 As Alex De Waal has argued, the HIV/AIDS epidemic “is being managed, not solved,”7 and its management has grown increasingly more organized from a newly completed headquarters: the WHO/Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Secretariat.8 Located in Geneva, a city renowned for its aggregation of world governing body headquarters focused on health and economics, the WHO/UNAIDS building houses administrators and serves as a tangible symbol for the efforts to improve global health in the face of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.9 In close proximity to other WHO administrative buildings, the International Red Cross, and the European headquarters of the United Nations (located in the former League of Nations headquarters, the Palais des Nations), this Swiss site provides a stark contrast to those regions most critically affected by HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. The UNAIDS headquarters (and by extension the WHO) in distant Europe also represents the uncomfortable separation between the global sick and healthy. In AIDS and Its Metaphors, Susan Sontag described the epidemic as spreading in “slow motion:” “The virus invades the body; the disease (or…fear of the disease) is described as invading the whole society.”10 In 2002, the Austrian architects Baumschlager & Eberle won the international competition for the new offices of the WHO/UNAIDS, presenting a design for the building as emblematic of important health operations while also questioning the long history of formal architectural ideas for world health headquarters.11 While formal analysis of the UNAIDS building is worthwhile, the project’s true merit lies in its rethinking of a previously heavy-handed UN mandate for aesthetic sameness, uniformity, and control of health by means of traditional standards and conventions.

The United Nations headquarters in New York City (completed in 1952), with an administrative block housed in a glass secretariat tower and a stone assembly hall to accommodate its worldwide constituents, makes a strong statement that symbolizes global governance and power. Reyner Banham described the tower’s glass façade as a “world-wide symbolic material of clarity, literal and phenomenal;” at the UN headquarters, it is “universally delivered in crisp rectangular formats…impervious to local accidents and customs.”12 Banham concludes: “[Glass] was therefore appropriate to all the aspirations of the founders of the United Nations, who gave it canonical form in their headquarters tower in New York.” The combination of the two elements, secretariat and assembly, had such a stronghold on the imagination of UN commissioners that these were mandated in the 1959 brief for the WHO headquarters, which were essentially to be built in the image of the UN building in New York.13

-

From 1851 to 1938, a series of annual international sanitary conferences were held in major European cities. With cholera overrunning Europe, the first International Sanitary Conference was held in Paris to produce international sanitary conventions. Each year additional themes were dealt with from cholera to plague to smallpox and typhus, to trade along the Suez Canal, to the wartime era and aerial navigation. At the time the conventions began, there was no world-governing agency to oversee public health emergencies. In response to these conventions and conferences, national health agencies were born where none had existed, and eventually, the 1874 Rome Convention saw a unanimous vote to create an international health body to collect, monitor and research information related to epidemics. This body was known as l’Office International d’Hygiène Publique (OIHP). World governance of public health would lead to the production of a set of conventions and standards for monitoring disease, but also more recently, conventions for disease prevention. These conventions would be adopted by national and local health agencies and cities to produce safer and healthier cities. The development of health headquarters here traces a history of international human health conferences and conventions desiring a permanent place from which to conduct worldwide disease surveillance. France and the United States had the first organized agencies; national bodies also tasked with overseeing international problems. The League of Nations eventually built a health administration wing that remained operational until the United Nations came to power in 1948; by 1966 the health department located within the League of Nations Health Administration wing would be relocated to the new WHO headquarters. ↩

-

Alex Lehnerer, Grand Urban Rules (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2009). ↩

-

Richard Matthew and Bryan McDonald, “Cities under Siege: Urban Planning and the Threat of Infectious Disease,” Journal of the American Planning Association 72, no. 1 (Winter 2006): 109. ↩

-

London’s cholera epidemics in the 1850s revealed key failures in the existing waterworks infrastructure, which led to new designs for receiving water into the house. ↩

-

“B.C. Lab Cracks Suspected SARS Code,” CBC News, 13 April 2003. ↩

-

Laurie Garrett, “SARS and Other Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance.” (paper, Jill and Ken Iscol Distinguished Environmental Lecture, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 16 June 2003); Hilary Sample, “Uberagencies, Design and Disease in the Contemporary City” (lecture, Canadian Center for Architecture, Montréal, 19 July 2007); Hilary Sample, “Uncovering Urban Patterns at the Daniels School of Architecture and Landscape” (lecture, Architecture, Therapeutics, Aesthetics seminar, University of Toronto, 27 February 2010). ↩

-

Alex de Waal, AIDS and Power: Why There is No Political Crisis – Yet (New York City: Zed Books, 2006), 3. ↩

-

The UNAIDS agency was established in the mid-1990s and focuses on HIV/AIDS viruses. In Africa, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is further complicated by communicable diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis. ↩

-

“Beginning of Construction Work On New WHO/UNAIDS Building,” World Health Organization Media Centre, last modified 28 June 2002 (accessed 14 July 2007). ↩

-

Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Picador, 2001), 153–154. ↩

-

“Beginning of Construction,” World Health Organization Media Centre. Ten architecture firms from seven countries were selected to participate in the competition, organized by FIPOI, a private not-for-profit foundation established by the Swiss Confederation and the canton of Geneva in 1964 along with the Federal Office for Construction and Logistics (OFCL). The project brief specified a moderately priced building not only in terms of construction, but also in terms of annual operating costs and maintenance. Baumschlager Eberle’s submission was chosen for its “highly contemporary, abstract and spacious design.” See here also. ↩

-

Reyner Banham, “Grass Above, Glass Around,” in A Critic Writes (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 209. ↩

-

These two strong, distinct forms—secretariat and assembly—first appear at Oscar Niemeyer’s Rio de Janeiro Ministry of Education and Health (influenced by Le Corbusier) which served as a model for the later UN headquarters in New York City. ↩

Among the fifteen architects of international stature to propose designs were Eero Saarinen, Kenzo Tange, and Jean Tschumi. Those schemes that diverged from the criteria of the competition brief were the first to be eliminated, including Tange’s curved, swooping concrete towers which converged at their tops. Saarinen’s scheme for a two-hundred-foot clear span tower lifted above an open-air entry plaza (with an assembly hall buried beneath) garnered second place. Since the New York City building, the UN had sought to repeat the forms of the tower and the cube in its many satellite projects, particularly in the development of the WHO headquarters and its six offspring, all established before 1965. Jean Tschumi won the international competition for the WHO headquarters (1959–1966) with a design that fully complied with the competition mandates—complete with tower and assembly cube—although several storeys shorter than the New York City building as a result of Switzerland’s height restrictions. Tschumi’s design wrapped the secretariat in an aluminum brise-soleil façade that enclosed the administration staff within. This flexible interiority could better accommodate the purpose of the headquarters, which needed to be able to respond to any emerging disease crisis in the world at any time and provide the space for teams to grow or shrink. Tschumi’s secretariat could house over one thousand people. Embodying the WHO’s mission statement at the time, the headquarters were constructed such that no other headquarters would need to be built again. But of course, the emergence of the HIV/AIDS virus would quickly alter that vision.

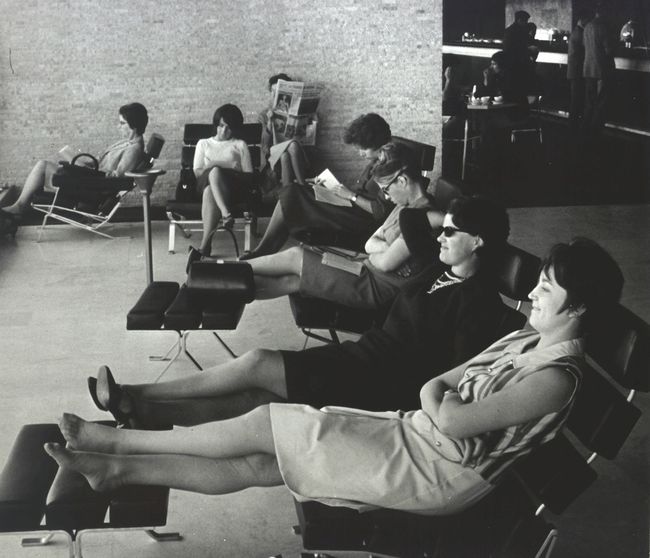

The new WHO/UNAIDS headquarters (2005) is a low, massive form surrounding a centrally placed open-air courtyard. Lining the courtyard perimeter are administrative offices stacked neatly atop one another, but unlike the WHO headquarters across the street, without a unifying or distinctive secretariat-like form. The building’s most important room—considering the debates, votes, and political resolutions which take place there—is similarly unarticulated. In other words, the forms found in both the UN and WHO headquarters as two-component object-like buildings are simply contained within the interior of the low mass at WHO/UNAIDS.1 The physical form of the WHO/UNAIDS building is designed to counter the image of the UN and the WHO, and instead of recreating the individual elements of secretariat and assembly, it places both programs within a single glazed skin. The design thus brings together disparate parts to make one whole. Even the furniture of WHO/UNAIDS headquarters assembly room supports this metaphor: a simple series of linear tables and plastic chairs are configured into the shape of a square. There is no speaker stage, no auditorium seating, no hierarchy—it is a simple, democratic arrangement. While the WHO/UNAIDS building is still in the family of the UN and the WHO, it is very clearly a break from the weighty secretariat-and-assembly combination of forms that was once mandated for replication as world-class design. The WHO/UNAIDS building suggests new thinking with regard to global health, or at least to the organization of global health surveillance, monitoring, and governance. It is perhaps too easy to suggest that the building’s low and horizontal form (as opposed to tall and vertical), implies that its “world-class” architecture here stands for the deliberate action of expediently managing and supporting the fight against HIV/AIDS on the ground.

-

Its low form and organization are more similar to Marcel Breuer’s US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC (1977). ↩

In AIDS and Power, Alex de Waal writes that African governments, civil society organizations, and international organizations have proven remarkably effective at managing the HIV/AIDS epidemic in such a way as to minimize political threat. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where one in six persons will contract HIV in their lifetime—causing the prominent journalist Laurie Garrett to refer to the disease as the “Black Death”—the threat of AIDS overturning African society seems to have little political cachet. Instead, there is a “smooth and coordinated functioning of their own institutions” and because of these efforts, with a “few important exceptions where different, intersecting stresses come together, AIDS is unlikely to cause socio-political crisis.”1 Management of the epidemic is efficient enough that “society is neither collapsing nor being transformed in revolutionary ways.”

The Commission for Africa produced the 2005 report “Our Common Interest,” which outlined characteristics of HIV/AIDS-patient environments in Africa, and the rate at which the disease travels across the continent: infecting one person per second.2 Compounding the situation is the painful growth of cities ever increasing in poverty and burgeoning slums, euphemized by De Waal as chaotic urbanization.3 In these conditions, 22.5 million individuals live with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa—compared to the roughly 1.5 million in North America—yet there is a single facility that provides treatment and care, and these in extreme conditions. Al Jazeera’s documentary series Saving Soweto (2009) presented the day-to-day operations of the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, known as Bara, in Soweto, Johannesburg, the largest acute hospital in the world set on 173 acres (70 hectares) with nearly 3,200 beds. Despite the UNAIDS’ aim of “Zero New HIV Infections, Zero Discrimination, Zero AIDS-related deaths” as published in its 2010 Global Report, South Africa’s epidemic remains the greatest in the world.4 In Bara’s medical admissions to Ward 20, for example, nearly 60 percent of the deaths are HIV/AIDS-related.5 Built from an abandoned British army barracks, Bara’s buildings and infrastructure are severely outdated and its connection to urban infrastructure equally despairing. Electrical shortages in the Soweto area frequently cause rolling blackouts; at the same time, although new buildings have been added to the campus, no new electrical services have been provided since its inception. Bara’s dilapidated structures include the twelve-storey nurses residence, labour ward, neonatal intensive-care unit, mortuary cold room, bulk water storage, intensive care unit, doctors’ residences, and paths and walkways between buildings.6 In addition to these problems, conditions have been so poor that the staff has resorted to acts of sabotage: disrupting laundry equipment (reducing the supply of sanitary linens), tampering with gas and generators, delaying treatments, and forcing operating theatres and wards to shut in order to draw further attention to Bara’s deficiencies in the hope of a fix.7 The proposed solution is to reduce the number of patients by half and create a network of six “mega-hospitals,” of which Bara will be just one. Yet the fulfillment of this intention remains uncertain.

The lesson to be learned from both the SARS and HIV/AIDS epidemics is that, in the current age, disease cannot be controlled through one fixed location: neither the hospital nor the headquarters alone can provide a cure. While modernism created utopian spaces filled with light and air and open, continuous space, today we understand space quite differently, to be in fact filled with particles, pathogens, and other invisible matter. While buildings are a setting for treatment, they do not directly treat disease on their own. But in combination, these buildings together with smaller-scale clinics, pharmacies, research laboratories, and others establish a necessary means of managing health and defending the city.

Urban disease is not neat, but messy, and requires technical solutions as well as amateur fixes. As urban health events emerge more frequently, it seems that deliberate acts of planning must increasingly address issues of emergency more as norm than exception.8 What this means for architecture is not a loss of formal, cultural, or aesthetic project, but rather the opposite—posing the question of how architecture can absorb these contemporary performance issues. Modern architects were unafraid to think about health as a provocation for new forms of the city. And if the city will always be at least partly sick, architecture too requires deliberate strategies with health in mind.

-

de Waal, AIDS and Power, 3. ↩

-

Bob Geldof, Our Common Interest: Report of the Commission for Africa (London: Penguin Books, 2005), 26. ↩

-

Geldof, Our Common Interest, 83. Growth most frequently occurs through informal as opposed to formal and organized economies. 72 percent of the total urban African population lives in informal settlements. See also de Waal, AIDS and Power, 3, which refers to chaotic urbanization. ↩

-

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic (Geneva: UNAIDS, 2010), 3, 30. ↩

-

See here also. “The World’s 3rd Biggest Hospital, in South Africa,” Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital (accessed 18 September 2011). ↩

-

Nicholas Bauer, “R150M Upgrade for Downscaled Chris Hani Baragwanath,” Mail & Guardian Online, 16 August 2011 (accessed 18 September 2011). ↩

-

Nonku Khumalo, “Bara Sabotage an Inside Job,” Soweto Live, 13 July 2011 (accessed 18 September 2011). ↩

-

Elaine Scarry, Thinking in an Emergency (New York City: W. W. Norton & Company, 2011). ↩

This text is an excerpt from Hilary Sample’s essay “Emergency Urbanism and Preventative Architecture” in Imperfect Health.